“It started with a suggestion to come up with something Beatle-ish, like ‘Ticket to Ride.’” The guitarist behind the 1960s pop hitmakers who sold more records than the Beatles and Rolling Stones combined

Louie Shelton played on the original recordings for the Monkees, establishing the sound that would help them become one of America's biggest pop groups

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From the late 1960s through the 1980s, few session guitarists were as in demand as Louie Shelton. His electric and acoustic guitar work graces hundreds of hit recordings, including Boz Scaggs’ “Lowdown,” Lionel Richie’s “Hello,” Neil Diamond’s “Play Me,” and the Jackson Five’s “I Want You Back,” “ABC” and “I’ll Be There.” As a member of the famed Wrecking Crew group of studio musicians, Shelton performed on sessions for the fictional TV band the Partridge Family.

And then there are his recordings for artists like John Lennon, Whitney Houston, Barbra Streisand, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, the Carpenters, Joe Cocker, Kenny Rodgers, the Mamas & Papas, James Brown and Ella Fitzgerald, among many others. He also played on and produced Seals & Crofts’ biggest hits, “Summer Breeze,” “Diamond Girl” and “We May Never Pass This Way Again.”

But Shelton’s rise from obscurity to become a studio session ace came about by a stroke of incredible luck. He was first introduced to the Los Angeles studio scene in the early 1960s by his friend and fellow Arkansan, Glen Campbell, who was then a member of the Wrecking Crew. Although Shelton occasionally subbed for Campbell, his only foothold in the tightly knit scene was doing sessions for B-grade publishing demos.

Article continues below“Glen Campbell's ex-drummer had joined my band in Santa Fe, New Mexico just before we went out to Los Angeles in 1963,” Shelton tells Guitar Player from his home on the Gold Coast in Australia, where he lives today. “And somehow he got in with the songwriting duo Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, doing their demos.”

That, in turn, led to Shelton working with the songwriters. By the time he met Boyce and Hart in 1965, they had written hits for groups like Jay & the Americans (“Come a Little Bit Closer”) and Paul Revere & the Raiders (“(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone”).

But the work wasn’t steady, and eventually Shelton drifted away from L.A. He was performing with Seals and Crofts at the Stardust in Las Vegas when Boyce and Hart approached him with the news that they were pitching songs for a new TV show about a fictional rock group called the Monkees.

“Boyce and Hart and came up to me and said, ‘We'd love for you to come back and do it with us,’” Shelton recalls. “So I started going back and forth for a while to do the demos for the Monkees.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the next weeks he made recordings with Boyce and Hart as they fought the competition to secure the Monkees gig.

“It was getting down to the wire as to whether Boyce and Hart were going to be accepted to do the music for the Monkees,” Shelton explains. “Other people were doing stuff as well.”

It was while working on one of Boyce & Hart’s new songs — “Last Train to Clarksville” — that Shelton struck music gold with a guitar riff that would forever change the trajectory of his career.

“It all started out with a suggestion to come up with something kind of Beatle-ish,” he recalls, “like a ‘Ticket to Ride’ riff, where the guitar starts the whole thing off.

“They brought in the TV show executives to hear what we had worked up so far. At that point they had the Monkees theme song, but all we had of ‘Last Train to Clarksville’ was my guitar riff. But just hearing that very guitar lick I came up with got them accepted to do the Monkees. ‘Clarksville’ is the one that sent them off and skyrocketed the whole progress of the project.

“I guess it just shows you the strength of having a guitar lick like that. You recognize it as soon as it comes on. It hits you. And evidently it grabbed them and won them over, too.”

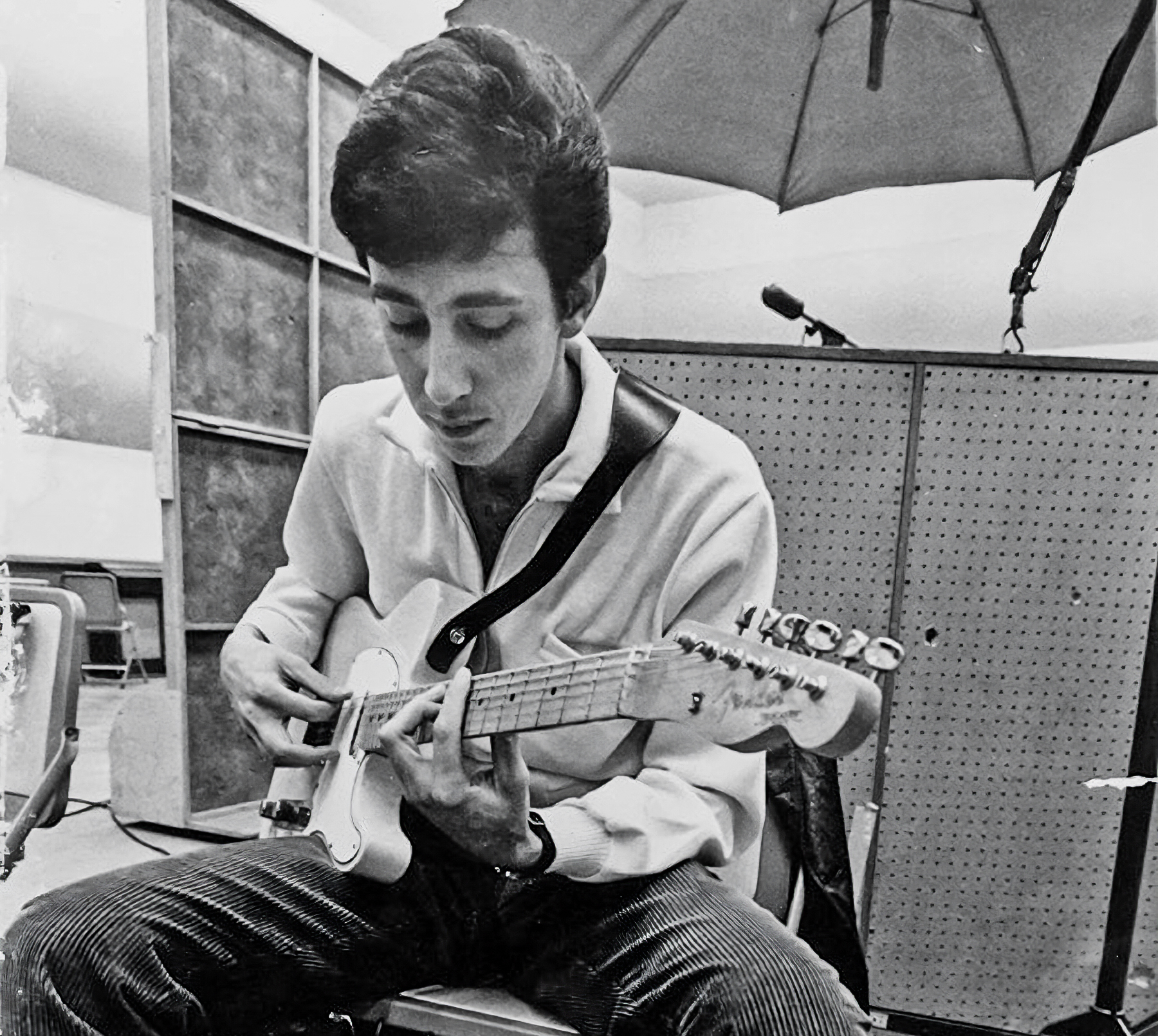

Once the tune was written, they entered RCA Victor’s studio to record it.

“I had my 1964 Fender Telecaster and a ’64 Fender Super Reverb that had four 10-inch speakers in it, which I had been using in the clubs,” Shelton reveals. “And as we were recording ‘Clarksville,’ they kept saying, ‘Turn it up! Turn it up!’ They wanted a loud and big, bright sound.”

Released in August 1966 as the debut single by the Monkees, “Last Train to Clarksville” rocketed all the way to number one on the Billboard chart. It was the start of an impressive run that would see the Monkees release four albums by the over the next 16 months. Aided by the success of their hit TV show, the group sold more records in 1967 than the Beatles and Rolling Stones combined.

In the wake of the single’s success, Shelton became Boyce & Hart’s full-time go-to guitarist.

“I basically played on all the stuff that Boyce and Hart did,” he says. “There were other people that did stuff for the Monkees too, using a different band that included James Burton and Glen Campbell on guitar.

“But with the Boyce and Hart band, none of us were even near top session players. We were all just starting out as session players ourselves. Yet, it was Boyce and Hart that got the majority of the hits”

Shelton’s love of all styles of music and guitar players hugely influenced his approach to the music they created. His musical versatility was especially evident on “Valleri,” another Boyce and Hart tune for the Monkees, where he added flamenco guitar stylings to the song’s pop framework.

“In my early days, I had records by flamenco player Sabicas, and a lot of those flamenco songs had a certain kind of chord progression to them,” he explains. “So when they started playing ‘Valleri’ with that E minor to D major to C major chord run down, to me it was very flamenco sounding.

“As a joke, I started playing these fast notes over those chords, like a flamenco thing. It was a direct steal from flamenco. I was just being a smart ass. But they said, ‘Oh, that's great.’ So I played it.

“What’s interesting is that I've gotten probably more response over the years from that guitar part than any other solos I ever did because it was such a strange thing to come out on a pop record. Later on, I felt bad about it, because I thought, Well, [Monkees guitarist] Michael Nesmith is going to have to fake these runs.”

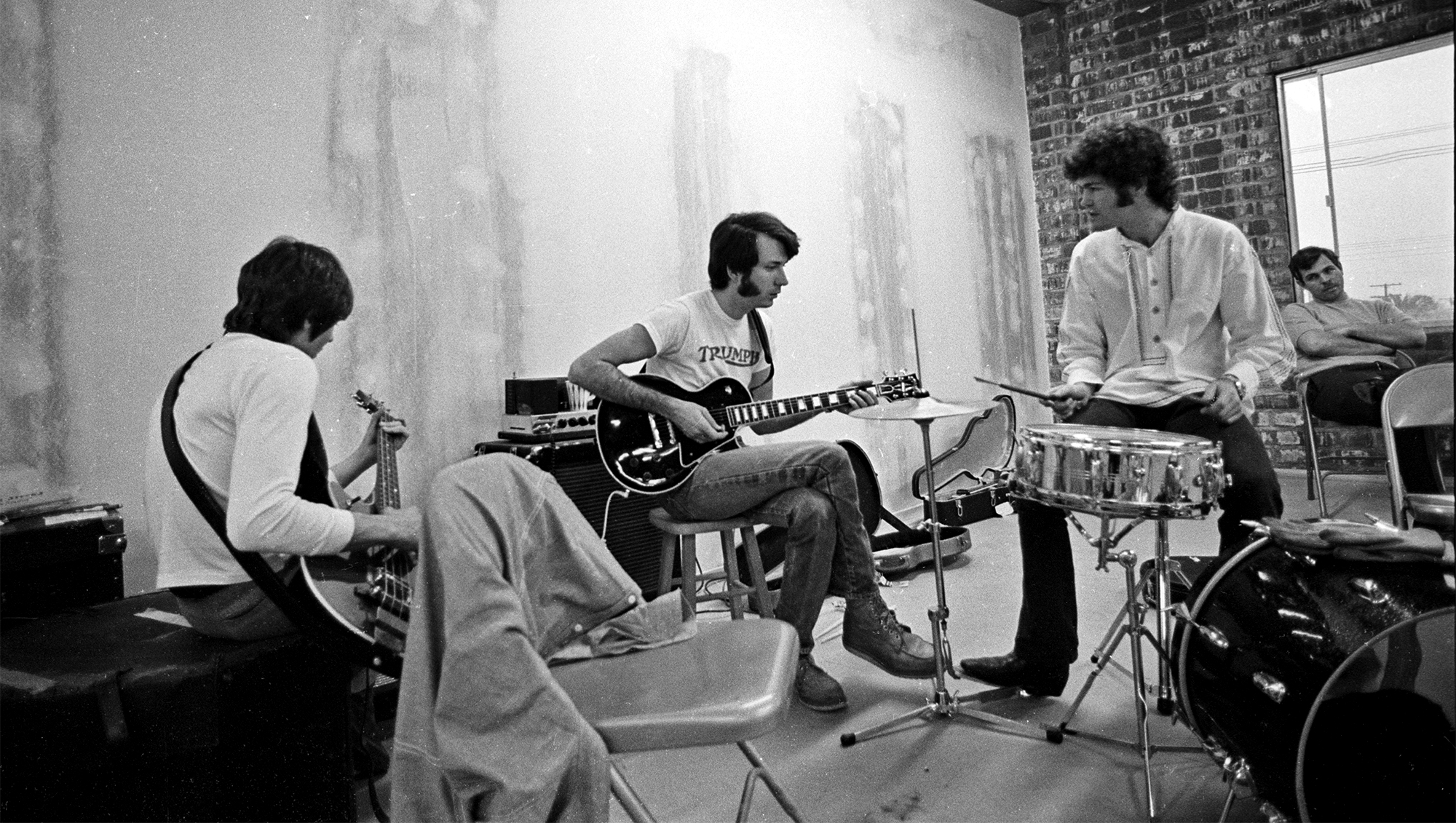

It's well documented that all the members of the Monkees were musically adept but were not allowed to play instruments on their earliest recordings or have input into the material that Shelton and the rest of the session crew were recording.

“They were never around to even have an opinion. I hadn't even met them until after we had done all the recordings,” he says. “We would come in during the daytime and do the tracks, while they were all filming the TV show. They would only come in later in the evening and do their vocals.

“But I do know to some degree that it was upsetting for them. And there's a lot that's been written about that, but I think they eventually accepted the fact that they wouldn't have been able to come up with that stuff. They were not at that point, yet.”

The Monkees would eventually convince RCA to let them play their instruments on their mid-1967 album Headquarters. Soon afterward, they performed on a tour on which Jimi Hendrix opened for them.

“When that first record came out and was a hit,” Shelton explains, “we had one little get together with the Monkees, showing them, ‘Here's what I played and here's how I played it, and just get as close to that as you can.’ We had that for just one day, and that was the last time I saw them.”

Shelton’s work with the Monkees led to more work opportunities, including with the Wrecking Crew. By then point, his pal Campbell had become a successful solo artist with songs like “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and “Wichita Lineman.” He departed the Wrecking Crew near the end of 1967, leaving the door open for Shelton to take his place. His mission to break into the studio session big league career was finally accomplished.

“The Monkees are what opened that door for me,” he says. “And coming into the Wrecking Crew, I was one of the younger members, as it was a kind of a time where they were beginning to drop off because of age or health or whatever, so new players were coming in.

“It had been a long road for me from my first group that I joined upon my arrival L.A. in ’63 — a folk duo called Joe and Eddie. I did a few albums with them, but there was a lot of time between that gig, the Monkees a couple of years later and finally becoming part of the Wrecking Crew.”

Shelton keeps busy today as he continues recording in Australia and the U.S., and sharing stories about his career both through his website and in videos on his YouTube channel.

Joe Matera is an Italian-Australian guitarist and music journalist who has spent the past two decades interviewing a who's who of the rock and metal world and written for Guitar World, Total Guitar, Rolling Stone, Goldmine, Sound On Sound, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer and many others. He is also a recording and performing musician and solo artist who has toured Europe on a regular basis and released several well-received albums including instrumental guitar rock outings through various European labels. Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera has called him "a great guitarist who knows what an electric guitar should sound like and plays a fluid pleasing style of rock." He's the author of two books, Backstage Pass; The Grit and the Glamour and Louder Than Words: Beyond the Backstage Pass.