“Duane Allman was sitting up on the top of the toilet, feet on the seat, and his little amp is right there.” Boz Scaggs on how Duane Allman and a spare hour of studio time led to one of the guitarist’s greatest recordings

As Scaggs drops his new album, ‘Detour,’ we revisit his historic 1969 session for “Loan Me a Dime” with a young Duane Allman

Most people of a certain age recall Boz Scaggs for his 1976 breakthrough album, Silk Degrees. With hits like “Georgia,” “Lido Shuffle” and — the number three hit — “Lowdown,” it was a must-own album that brilliantly fused elements of blues, rock and soul with four-on-the-floor disco beats, making it a record you could rock to as well as dance to, all of which gave it remarkably wide and diverse appeal.

Scaggs has just released Detour, his first new album in seven album years. It’s an intimate affair that began as an exercise in singing just for the sake of it. Among the tracks are renditions of Allen Toussaint’s “It’s Raining,” the sentimental standard “Angel Eyes” and a reinterpretation of “I’ll Be Long Gone,” a fan favorite from Scaggs’ 1969 self-titled second album, which is often considered his debut record.

That 1969 album is significant for guitarists. Among the studio players who appear on it is guitarist Duane Allman, making one of his many appearances on disc before the Allman Brothers Band became a going concern.

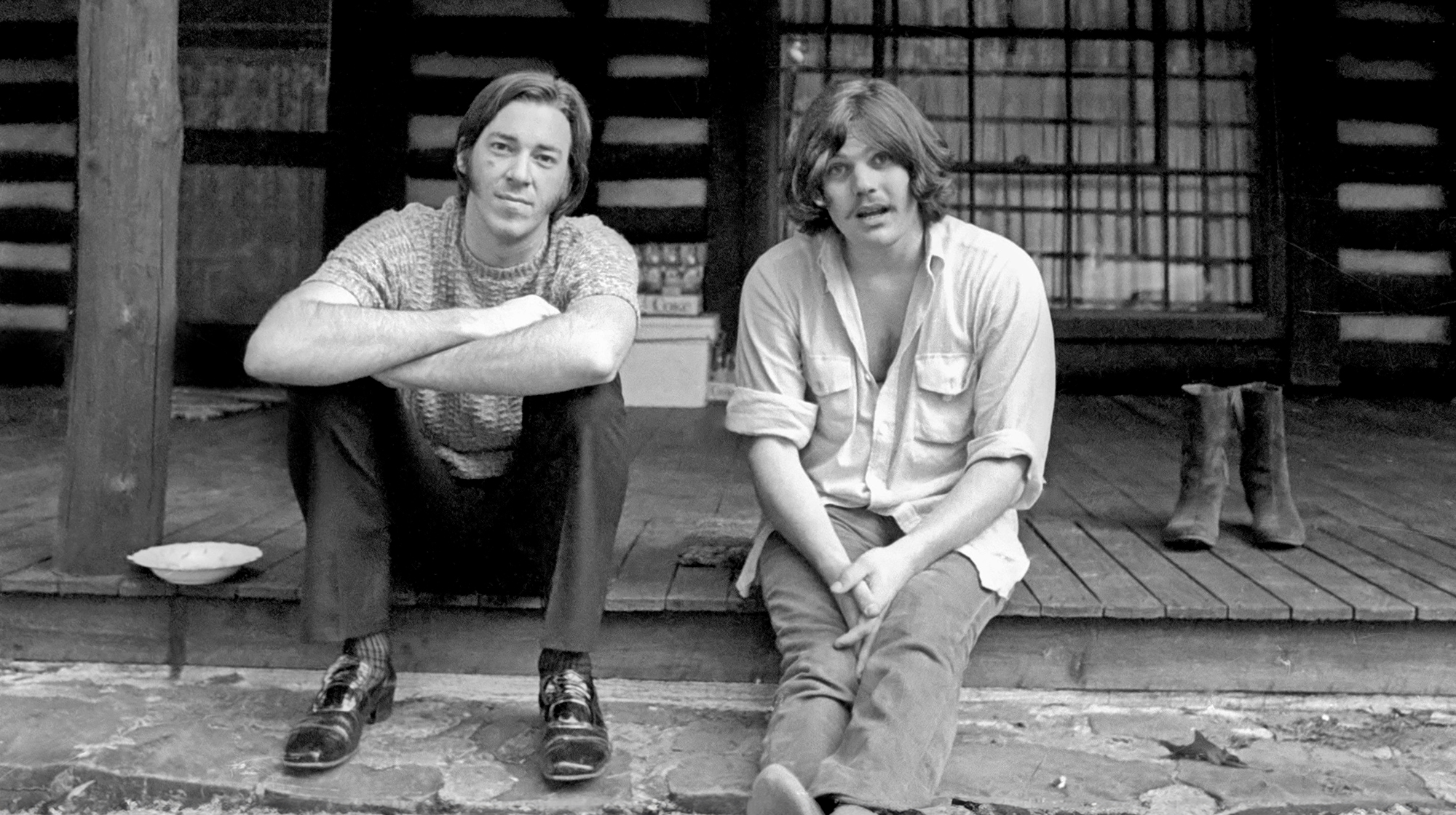

As for Scaggs, his self-titled record was the start of a long journey as a solo artist. Scaggs had been the vocalist in the Steve Miller Band but left after the group’s second album, 1968’s Sailor, to continue a solo career he had launched in 1965 with his debut album, Boz.

Back home in San Francisco, his neighbor and friend was Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone magazine. Wenner liked Scaggs’ songs and encouraged Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records to give his demo a listen. He agreed with Wenner, and signed Scaggs to record an album, with the Rolling Stone publisher as his producer.

Scaggs and Wenner chose Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Sheffield, Alabama for the sessions. Wenner, an early champion of Allman, the young electric guitar player from Macon, Georgia, wanted him to perform on the record. It seemed easy enough: Allman had been a regular at Muscle Shoals and nearby FAME Studios, where he cuts many sides, including Wilson Pickett’s “Hey Jude.” (His guitar work on the song so impressed Eric Clapton that Clapton had to pull his car off the road to listen to it. He didn’t know who Allman was the time, but he would soon become a fan.)

There was just one problem: Allman had moved back to Macon, Georgia, to work with his new group, the Allman Brothers Band. Fortunately, Wenner convinced him to come back to Muscle Shoals for the week’s work required to make the record.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“In those days, everybody who worked at Muscle Shoals, you get one week,” Scaggs tells Mark Hummel’’s Harmonica Party. “You go in on Monday morning, and you come out on Friday night or Saturday morning, and you're done.”

As Scaggs recalls, the sessions had wrapped up on Friday evening and the musicians were packing up to go home. “Everybody’s putting their stuff in their cars, just loading out.”

That was when someone — Scaggs thinks it was Wenner — note that they still had time left on the clock .

“He says, ‘You got time here. I mean, we're all here. Is there one more song you want to do? Is there one last thing?’”

Scaggs’ mind went to a blues tune he’d heard performed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at a show by guitarist Elvin Bishop and his singer, Jo Baker.

“They did a song by Fenton Robinson — I didn't know his name at the time — called ‘Loan Me a Dime.’” Scaggs explains. “It was right out of where I come from, the blues.” Scaggs had never heard the song before. “I just heard her [Jo].”

Scaggs could recall the melody and changes, but he didn’t know the words. A quick call to Baker in San Francisco unlocked the key.

“She gave them to me, and I said [to the band], ‘It goes like this, and it’s a minor blues.” Scaggs had no doubt the musicians were up to the task. “You know, with that rhythm section and Duane Allman?”

But because Muscle Shoals was a small studio — “about the size of a double garage,” as Scaggs recalls — most tracks, including those for Scaggs’ album, were cut over several sessions, with overdubs, because it was difficult, if not impossible, to squeeze all the musicians required for an arrangement into the studio.

With no time left for overdubs, the musicians had to be strategic about utilizing every available space in the building so that they could record as a group.

“There was a cloak room and there was a bathroom and there was a control room,” Scaggs recalls. “The horn players had to go back where the Coke machine was [in the cloak room]. There's a little closet, and they had three or four horns, or maybe five horns.

“And they put me back in some little office or tape room, or something, with a microphone in it.

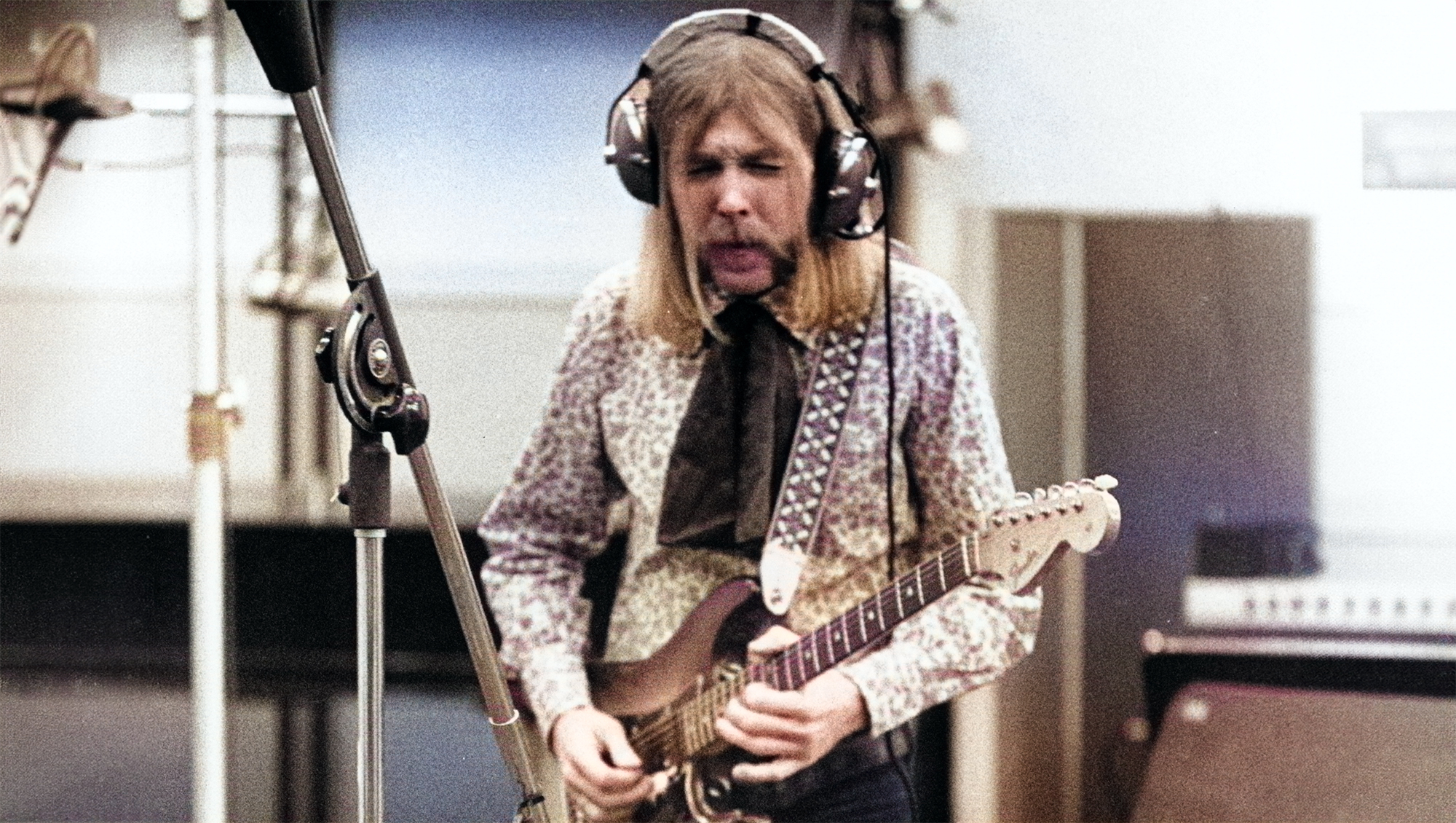

“Duane Allman was sitting with his amp in the toilet. He was sitting up on the top of the toilet, feet on the toilet seat, and his little amp is right there, and he crowded in there with the headphones on. And he's got a great tone in there, with the little amp and the ambience in that room.”

The band rehearsed the song with the tape machine running, just in case magic struck. And it did.

“We ran the song down, and came to the end,” Scaggs continues. “And, as happens, somebody just kind of kept playing: It was the rhythm section. They just kind of started going into a little lope with it, going through the changes with it — double time, boogaloo, and then it went into this kind of a shuffle, a full-on four-on-the-floor shuffle.

“And, of course, Duane is blowing. And it was probably 15, 16, 17 minutes long. And everybody went. Whoa!”

The take was fantastic, but as Scaggs recalls, it was not complete. The second take was, and, as he notes, “the energy was a little different.”

Why? “Duane was the main difference.”

The guitarist had found his groove, and the result proved to be an indelible achievement in his short life. Indeed, Allman’s performance on “Loan Me a Dime” is considered a highlight of his career. And it all happened on the turn of a dime, so to speak.

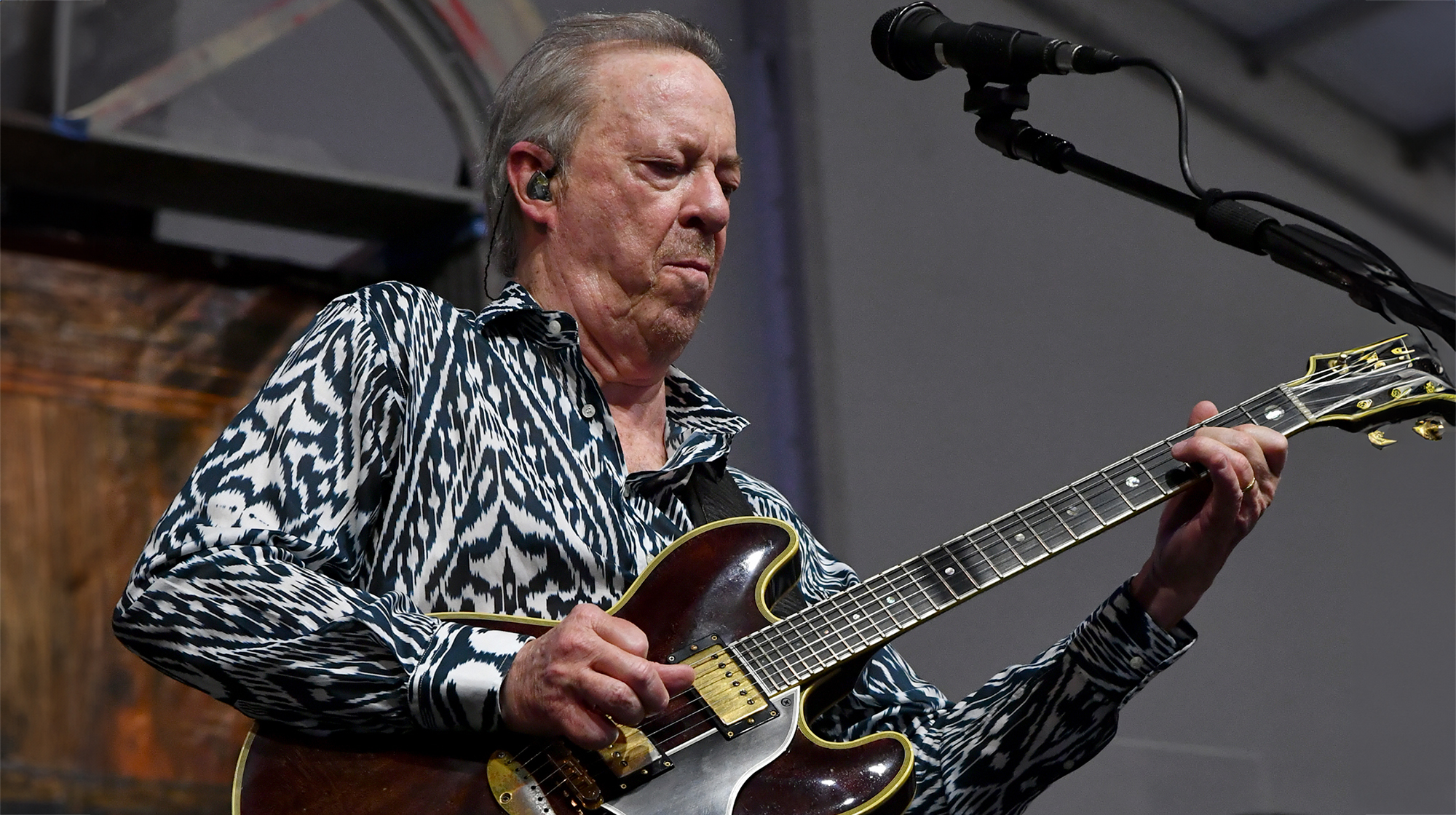

For all the lightning-in-a-bottle excitement of that session, Scaggs says his favorite memories of Allman come from after the album was completed. Duane asked Scaggs to drive him to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to visit a traveling guitar salesman camped out at a hotel.

“He had one of the greatest collections of original Dobros and National steel guitars, and Duane got word of it,” Scaggs explains. As no one else had a car, the singer was asked to help Duane make the journey.

“We spent the day driving up there and looking at guitars and driving back,” Scaggs told The Herald-Dispatch of Huntington, West Virginia. “Duane was a wonderful and lovely guy — a really focused, solid, hard-working and direct guy. He was a really nice man. And, of course, he was an enormous talent and a real easy and wonderful guy to be around.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.