“He says to me, ‘Keep vamping, just jam,’ while he’s having a heart attack. Then he started grabbing his chest.” The show that ended David Bowie’s touring career — and the song that became his last hit

Read one of Guitar Player's top stories of 2025

Guitar Player is closing out 2025 by republishing 25 of your favorite stories from the past year. We thank you for spending the past year with us and look forward to bringing you more of the stories you want in 2026.

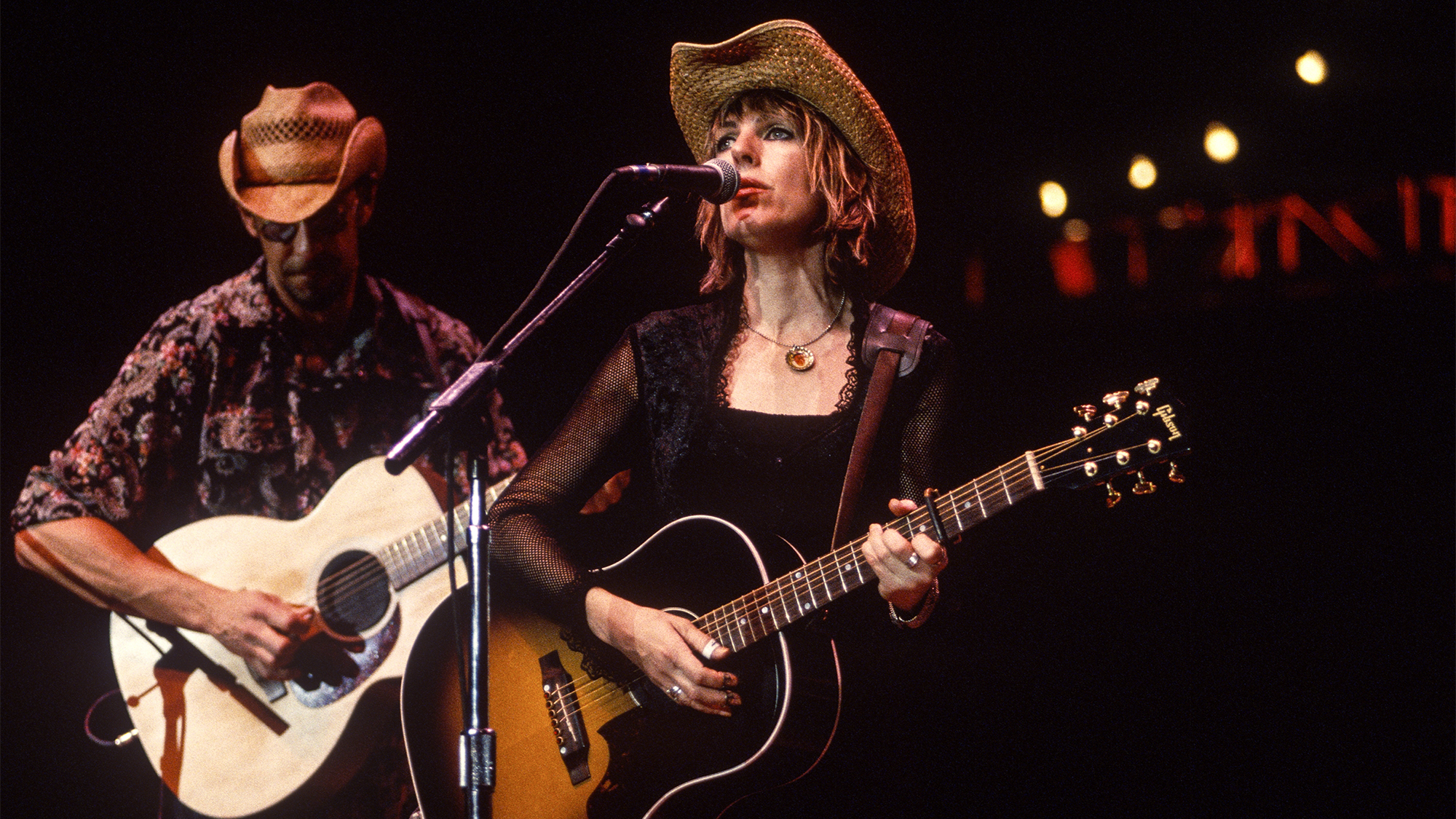

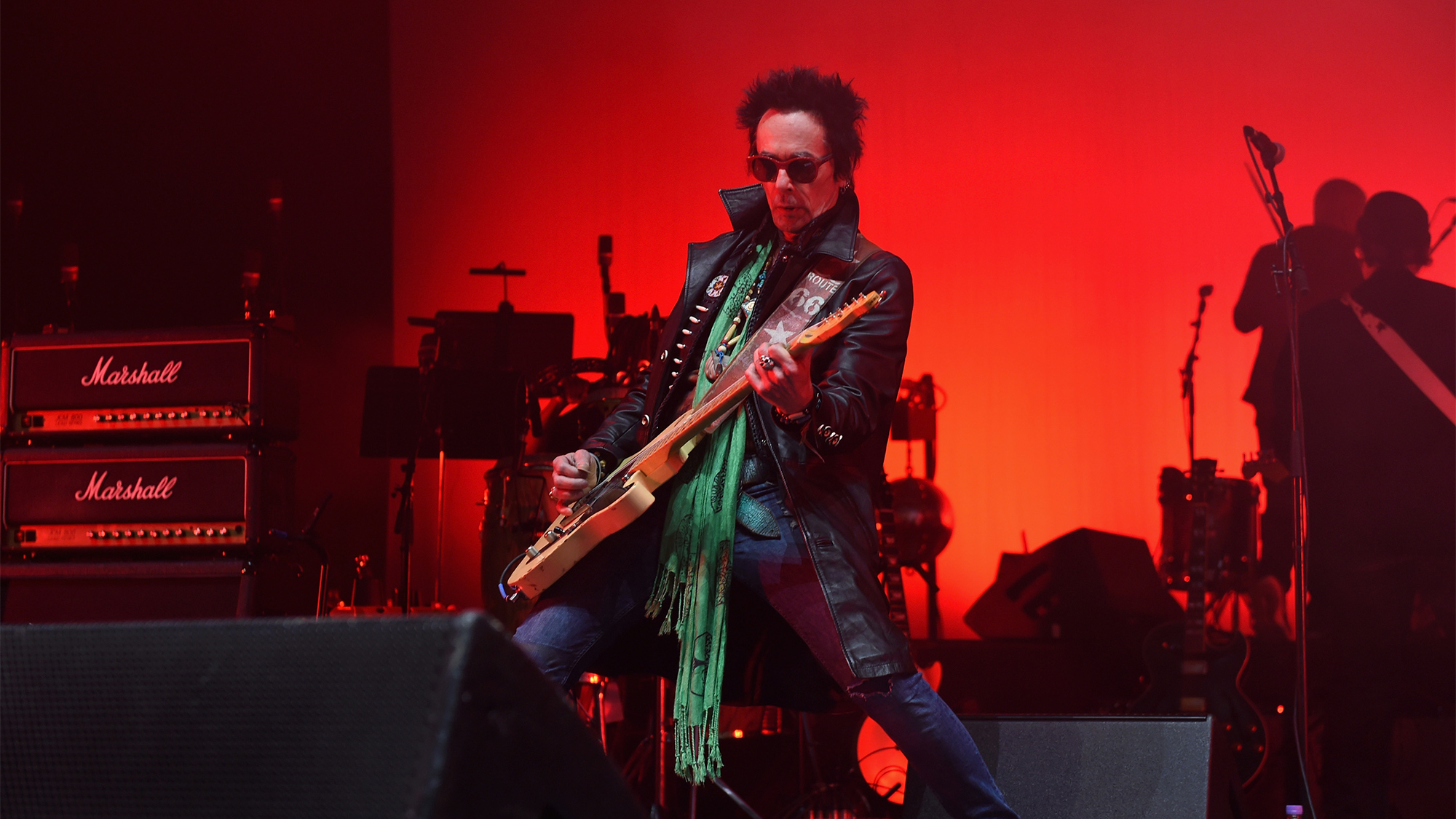

David Bowie worked with many guitarists throughout his long career, from Mick Ronson to Carlos Alomar, Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew and Reeves Gabrels. But there was one player he returned to several times, from the 1970s to the final years of his life: Earl Slick.

What did the Brooklyn-born guitarist give him that no other player did?

“I have theories about that,” Slick tells Guitar Player via Zoom, from the kitchen of his home in New York City, while smoking a morning cigarette and opening a bottle of Gatorade. “One of the things was that, when it came down to needing that rock and roll guitar player, that was always me or Mick. And Mick left us a long time ago.” (Ronson died in 1993.)

As for the others?

“All those guys are wonderful,” Slick says. “But none of them are rock players. So he came back to me for that. That’s when I got called in.”

Earl Slick was not a constant in David Bowie’s universe. Few were. But the guitarist — born Frank Medeloni nearly 73 years ago — was a mainstay. He arrived in 1974, following the demise of the Spiders From Mars and Ronson’s exit, to perform on Bowie’s Diamond Dogs tour. He played on the Young Americans and Station to Station albums soon after, then returned in 1983 for the Serious Moonlight Tour as a last-minute replacement for Stevie Ray Vaughan, who famously lent his electric guitar stylings to Let’s Dance, Bowie’s 1983 commercial smash.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

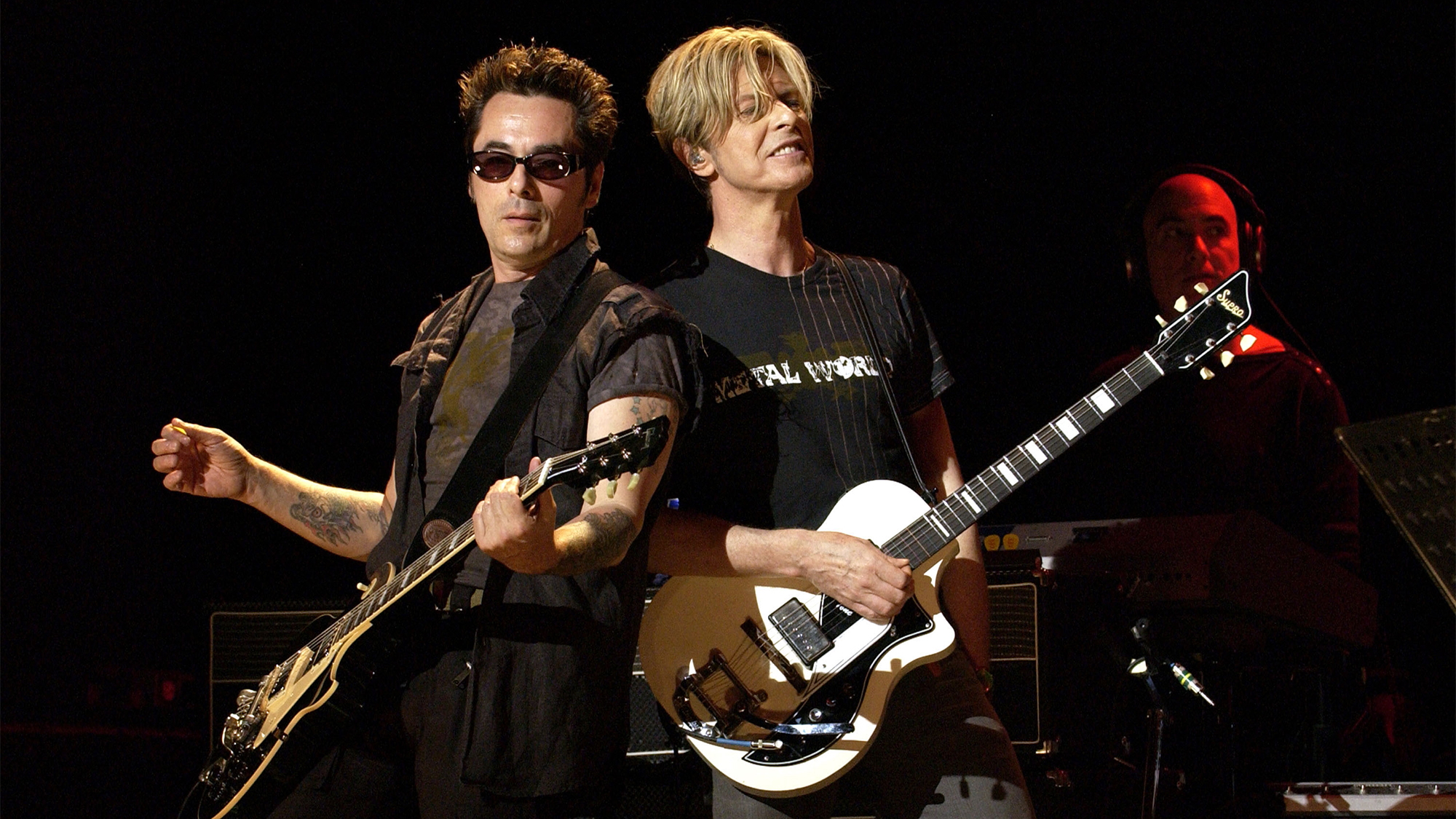

Nearly 20 years would pass before Slick came back once again on the tour for Bowie’s 2002 album, Heathen. That led to him working on its follow-up, Reality, and performing on the subsequent A Reality Tour, a celebrated groundbreaking global stint that was the biggest and longest of Bowie’s career.

It was there that he witnessed Bowie’s heart attack on June 23, 2004 while onstage in Prague, along with his subsequent decline.

“It was amazing how he went from looking great to looking pretty ill — like, overnight,” Slick says. “We were just a month shy of a year being out.”

Bowie recovered, but he canceled the remaining shows and never toured again. Slick returned for his penultimate album, 2013's The Next Day, making him the only guitarist to have worked with Bowie over such an extended range of the performer's career.

The music from Slick’s latter tenures with Bowie is generously chronicled on the upcoming box set David Bowie 6. I Can’t Give Everything Away (2002–2016), due out September 12. It’s the latest and, theoretically, last in a series of massive completist collections, and features Bowie's final albums, including Reality and The Next Day, as well as the A Reality Tour live album and a previously unreleased recording from the 2002 Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland.

Also included is “Isn’t It Evening (The Revolutionary),” a track from Slick’s 2003 solo album, Zig Zag. Co-written with and featuring Bowie, it hit the Top 10 on several U.K. charts when it was re-released there last year.

It all serves to underscore the vital position Slick held with Bowie during the final era of his career, making this an apt time for him to weigh in on his impactful years with the chameleon of rock.

Was there much difference being Bowie’s “rock” guitarist compared to other things you’ve done?

Well, with David I did have to have a pedalboard to cover 40 years of recordings or whatever. And I hate pedals, especially overdrive pedals. But you needed certain things. You definitely needed two delay pedals just to cover “Heroes,” just to get it bouncing all over the place.

But I got a lot of free rein from David. I could literally change up bits and bobs during a show, and he liked it, actually. If you look through the concert videos, you’ll see really weird arrangements of songs and stuff. ’Cause you get bored if it’s the same song every night, so sometimes you change things up, and he liked that I did that. I had a lot of freedom to just ad lib, everywhere.

You’d been out of the Bowie orbit for about 15 years when he reached out to you around 2002. How did that come about?

Omigod. Reeves had left and David was looking for a guitar player, so his people tracked me down through a web site. It was called Slick-something-or-other, and it had all these old demos we kept putting out. That’s how he found me.

The webmaster called and said, “I just got this email. It’s a New York number and they seem to really want to get in touch with you.” He said it was from Isolar, and I said, “I know exactly who that is. It’s David.” [Isolar was the name for pair of Bowie’s tours in 1976 and 1978.]

We got a phone call saying, ‘Sit tight for a couple of days. David needs to rest. We’re gonna take a few days off.’”

— Earl Slick

The A Reality Tour was Bowie’s last and, many think, one of his best. What was your experience with it?

That was a fun record to play live, especially the rockers — the title track and stuff. It was the best touring band I ever played in with David. The combination of people — it was absolutely drama free, and I’ve never seen him that relaxed and happy on a tour, ever.

It was also the tour that was notoriously ended by his health issues. What do you recall from that Prague date when he had his heart attack?

It was a really weird gig. At first I couldn’t figure out what was going on. It was hotter than hell in the place, and I could see he was having a hard time hitting some notes. I thought he was just baked. We were all baked.

I think we were doing “The Jean Genie,” and he goes to me, “Keep vamping, just jam” — this, while he’s having a heart attack. Then he started grabbing his chest and the tour managers came over and dragged him off.

A few minutes later, he comes back and joins us. He lasted about a measure or two and then he walked off. They said that he had a blocked nerve, whatever that is, and that diagnosis was wrong.

We did the Hurricane Festival in Germany a couple days later; I went over to talk to him, and he was feeling horrible. We did the whole show and then we got a phone call saying, “Sit tight for a couple of days. David needs to rest. We’re gonna take a few days off.”

So we just hung out in Hamburg. Nobody’s saying anything to us.

And then we get phone calls saying, “Guys, we’re done. You gotta go home.” We didn’t get an explanation; we all knew he was probably getting some kind of surgery, but we weren’t getting any details about it.

When we did “Heroes” at the Hurricane Festival, I swear to God it’s one of the best vocal performances he ever did of it. Two hours later, probably, he was in the hospital.

Was the idea of him playing live again ever broached?

It was. We were working on The Next Day; just as I finished up my work on the track “Set the World on Fire.” We were listening back in the control room and he looks at me and goes, “This would just kick ass live.” I looked at him ready to say something, and he goes, “Don’t even think about it.” [laughs]

That was the discussion we had about going on tour again. That was the whole discussion, and he said, “Don’t think about it.” I could see it in his eyes. I’d been with him so long, I knew he was dead serious. He ain’t going nowhere.

It was disappointing, because I really thought we would have at least one good tour left in us. This was the summer of 2013, so it’s possible that he might’ve been ill already, with the cancer. We’ll never know, but I think it’s a possibility.

The Next Day was another kind of odd reconnection, wasn’t it?

Yeah, it was typical David. He started making that record around 2011, I think, and everybody who was brought in had to sign an NDA. I’m talking to some of the guys on the phone and nobody says a word.

In the meantime, this friend of mine, a surgeon, he built a car, a Cobra, and I had this blues gig I was doing near his house in Montclair, New Jersey. I go visit and he says, “Let’s go for a ride in the Cobra before we go to the gig.”

I swear to God, if we hadn’t blown up the car, I might not have been on that record.”

— Earl Slick

We drove for a little bit, and then the car started to do weird shit, like sputtering and stalling out. So he stops the car and two seconds later a big flame comes out of the engine. We call 911 and the fire department comes, and the cops come, and there’s TV. I guess one of the reporters figured out I was in the car and the word gets out on the Internet.

The next day I get a text from Bowie: “Oh God, I saw this accident. Are you okay?” I write back, “Yeah, I’m great, I’m fine. How are you?” “Good.” Then I get a few more messages over the course of the next day or two, like, “How you doin’? What have you been up to lately?” This is not a typical thing with him.

So finally I’m like, “Okay, are you trying to get to a point? What is it?” And he was, “Well, we’re making this record, and I need you to come in for a week or so and work on it.”

I swear to God, if we hadn’t blown up the car, I might not have been on that record. That’s just him: It’s out of sight, out of mind sometimes, and then it’s, “Wait a minute — Slicky could do this or that.”

Was there a standard operating procedure when you worked together?

We’d sit there and brainstorm, especially on the overdub bits. Both of us always like to have some kind of melodic lick in there somewhere, some signature in the song, and we’d just knock ideas around.

Like the lick on “Valentine’s Day,” the signature lick at the beginning, we sat there and bounced it around for about 10 or 15 minutes and that lick popped out and there it was. A lot of that kind of stuff was done on the fly; we never spent lots of time. As soon as we heard something that clicked, that was it. That’s the best stuff, when it just comes out from outer space or something.

What is your sense of the late-period Bowie compared to your previous years with him?

Well, back in the early days — this not speaking out of school, ’cause it’s pretty well known — a lot of drugs were involved, and a lot of cocaine. Between the drugs and him having management problems and all that, he was on another planet.

And then as the years went on he changed, like we all do. In the 2000s a sense of humor was there that was never there in the early days. He was funnier than hell, and he was more approachable. He turned into... I wouldn’t say a different person, but the real him came out.

How did you approach guitar choices for your work with Bowie?

I love Telecasters. I’ve always been a Tele player. But for the Heathen tour he said, “We do need a humbucker on some of this,” so I grabbed some Les Pauls, and by the A Reality Tour I was using pretty much my Les Pauls most of the show. I don’t think I used my Teles at all on that. I did have a Strat I used for a few things, but most of it was Les Paul.

It got on the charts and we had a hit single. Funny how timing works. And I’m really glad it’s on the box set, because it turned out to be his last hit.”

— Earl Slick

Having “Isn’t It Evening (The Revolutionary)” on the box set is a nice postscript, especially after its success last year in the U.K.

That’s a weird one. I was living in Portland [circa 2002], and I just started to toodle around with my guitar, and all of a sudden I started coming up with stuff and recording bits and pieces. I ended up with a lot of them, so I called up Mark Plati and said, “When you get some time maybe we can cut an instrumental record. I got some good ideas.”

I didn’t realize he was in the studio when I called him. David was there, and David says, “Earl, I heard Mark say you guys were gonna do some recording. Maybe I’ll play some tambourine or something. Maybe I’ll even sing one, or we can write one.”

So I sent him a half-dozen bits and he picked the one that eventually turned into “Isn’t It Evening.” We recorded it, and we released it during the A Reality Tour, which turned out to be a bad idea, because my record got buried in there.

So I just sat with that track for years and thought, One of these days, I’ll release it as a single. Then Penguin Books approached me about the memoir [Slick’s recently published Guitar: Life and Music with David Bowie, John Lennon and Rock and Roll’s Greatest Heroes]. I said, “Ah, that’s the time to do it!”

So we rearranged it and it came out about two months after the book. It got on the charts and we had a hit single. Funny how timing works. And I’m really glad it’s on the box set, because it turned out to be his last hit.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.