“We weren’t looking for perfection; we looked for mistakes that were really good.” On the anniversary of Marc Bolan’s death, we look back at his life in music and his greatest album: ‘The Slider’

Producer Tony Visconti recalls the man and the musician who was not only behind the birth of glam rock but also celebrated as the godfather of punk

Although Marc Bolan only scored the one U.S. hit — “Bang A Gong,” in 1971, with his band, T.Rex, his influence on the artists that followed him, particularly in the States and the U.K., was immense. From 1970 to 1974, Bolan became, arguably, the biggest act in the world, with a level of adulation that was the equal of Beatlemania. “T. Rextasy,” as it was nicknamed, saw Bolan score a run of 14 hit singles and six albums that generated worldwide sales of around 50 million in a four-year period.

America was strangely resistant to the charms of the “bopping elf,” perhaps unready to embrace the camp excesses of glam rock. Nowadays, Bolan’s image may seem a little tame, but back in 1970, male pop stars weren’t experimenting with glitter under their eyes, wearing feather boas and the occasional item of women’s clothing. As striking and revolutionary as his image was, the most crucial reason for Bolan’s success was the music. He created a body of work that transcends time and genre to sound as fresh as the day it was released more than 50 years ago.

Perhaps surprisingly, Bolan’s career trajectory was not unlike that of Bob Dylan, with the transition from acoustic folkie in Tyrannosaurus Rex, a duo that he had formed with Steve Peregrine-Took, to fully fledged electric warrior, with the inevitable accusations of sell-out and Judas from his original audience. Born Marc Feld, his first single, released under the name Toby Tyler, in 1964, was actually a cover of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

The single was a flop, but Bolan was undeterred and recorded another single the following year, “The Wizard,” which included Jimmy Page among the studio musicians. Again failing to score much success, Bolan recorded some acoustic demos before joining psych-pop band John’s Children. The single that Bolan wrote for them, “Desdemona,” should have seen Bolan make the breakthrough in 1967, but was banned for ‘suggestive’ lyrics by the staid BBC.

Bolan’s unflappable self-confidence, and already fully formed ego, refused to allow him to countenance failure. The formation of Tyrannosaurus Rex in 1967, saw him achieve cult status, with a largely acoustic set featuring Tolkienesque lyrics and nonsense poetry in the spirit of Edward Lear. Although the band released three reasonably successful albums, Bolan’s love of rock and roll and the power of an electric guitar couldn’t be denied. Much like Dylan again, Bolan had already peppered his pre-T.Rex albums with enough hints that there was a six-string weapon of serious intent waiting to be unleashed.

The breakthrough came when the band shortened its name, ditched the acoustic/mystical dabblings and went for the throat with the release of “Ride a White Swan,” in 1970. A simple, straightforward rocker, with a riff largely based on classic Sun rockabilly singles and a devastatingly effective guitar solo, the record was a worldwide smash and saw Bolan transformed overnight into a fully fledged teen idol.

Bolan worked with producer Tony Visconti from 1968, when the transplanted New Yorker produced the second Tyrannosaurus album, Prophets Seers and Sages: The Angels of the Ages. Visconti produced every subsequent Bolan record until 1974’s Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow, and his string arrangements were a key part of the creation of the distinctive T.Rex sound.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Visconti occupied a unique position in that he was also producing David Bowie’s records over the same time period as he was adding his magic to the Bolan mix. Bolan and Bowie were both friends and rivals; Bolan hit superstardom before Bowie, but had to suffer the frustration of seeing Bowie’s career continue to boom as his own went into something of a decline by the end of 1974.

David Bowie was both Marc’s friend and his — as perceived by Marc — enemy.”

— Tony Visconti

As Visconti remembers, “David was both Marc’s friend and his — as perceived by Marc — enemy.”

As Bolan’s star waned, and he started to chase trends rather than create them, it is tempting to wonder what might have been if he’d reunited with Visconti.

“That was almost on the cards, because right after David appeared on Marc’s weekly U.K. TV show, he took Marc to Soho to see my studio on Dean Street. Marc had never seen it before, and Marc said to David that it would be great to work there with Tony again.

“I would have encouraged him to think about experimenting with new sounds, new chord changes even. I would have encouraged him to be adventurous and to keep an eye on the top of the charts.”

Bolan made a string of great albums, and his best record for most of his fans is The Slider. Bolan was at the pinnacle of his success, and unsurprisingly was starting to become a little affected by it all.

“Yes he was. His ego was through the roof,” Visconti says, laughing. “As if it wasn’t bad enough when he was Tyrannosaurus Rex, now that he had validation with the run of hits, he was quite full of himself.

“It was often in an endearing way, though he could be quite vicious sometimes when he lost his temper, at other times he was very kind. People do often go through a mental upheaval when they become successful after years of struggle and rejection.”

Success may have altered Bolan’s ego, but he hadn’t lost his focus on his music. Visconti remembers that his work ethic was as strong as ever.

He often recorded with the fans in mind; he wasn’t very concerned with getting the respect of other musicians — that didn’t matter to him.”

— Tony Visconti

“He was very conscientious. He often recorded with the fans in mind; he wasn’t very concerned with getting the respect of other musicians — that didn’t matter to him, but he wanted to give the fans what he thought they wanted and that required a lot of work. All of us worked very hard on The Slider.”

Bolan was a fast worker, but first and foremost, he was concerned about the feel of a track.

“We were both on the same page with that,” Visconti explains. “We weren’t looking for perfection; we looked for mistakes that were really good, maybe kind of funky that would give a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. We always looked for that.”

Bolan was a prolific writer, and Visconti recalls some of his working processes.

“I never heard demos and I don’t think the band did either. They were learning those songs on the spot. Marc had written a lot of songs, but he didn’t make many demos. What he had was a school notebook, full of lyrics. I took a peek in there and he had about 50 songs written — just the lyrics, but I think he knew the chord changes for all of them in his head.

“When we started recording the album, he’d get the book out, turn the page and say, ‘We’re going to do this one.’ Then he’d sit there with his guitar and play the song all the way through to us. That was how they would learn it.

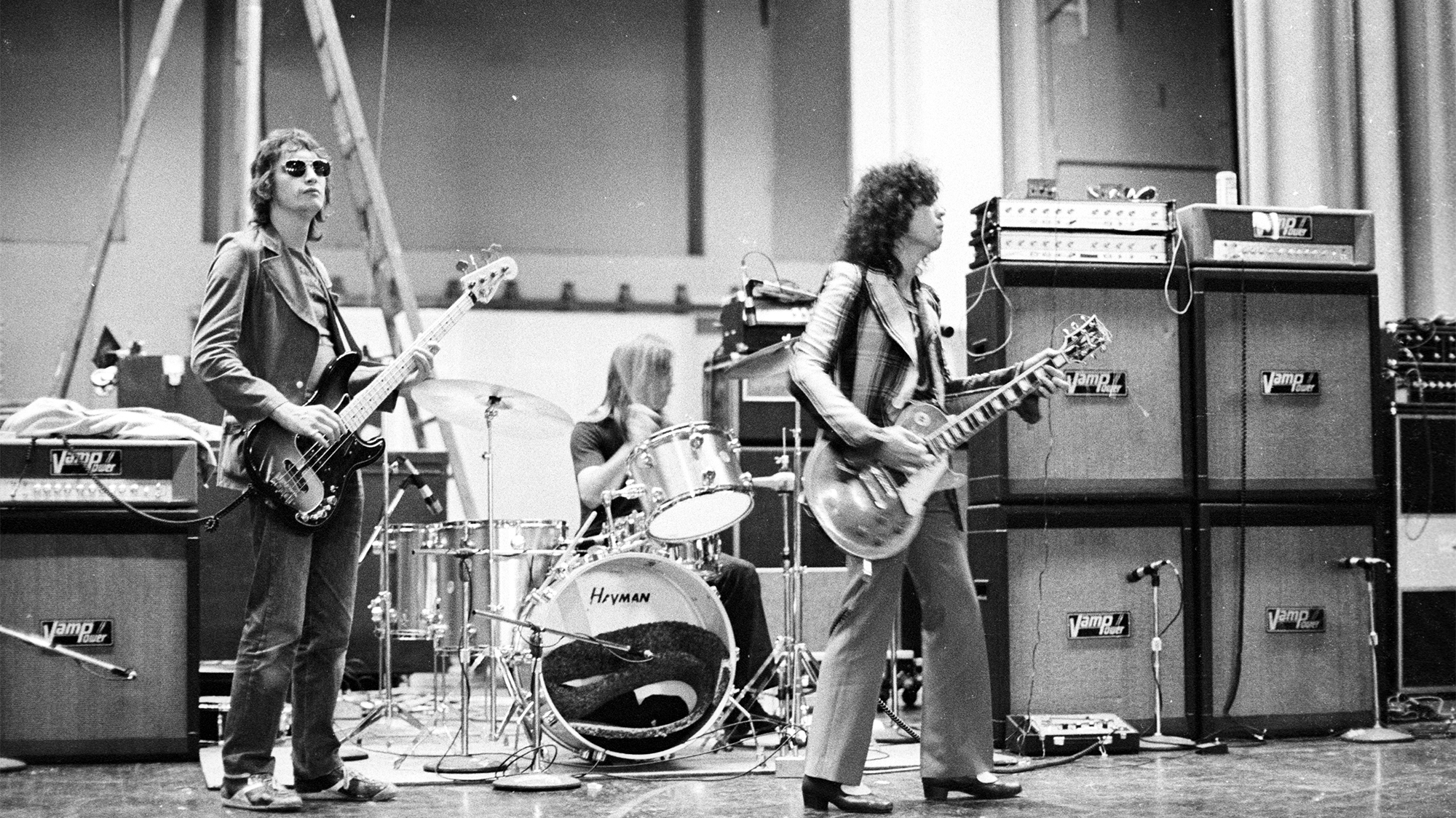

“Steve [Currie] would find a complementary part on the bass, Bill [Legend], would find the right groove pretty quickly and Micky [Finn] would weave his congas around what they’d created. I would already be thinking about string arrangements.”

He had booked three days to get 18 songs done, whereas Bowie would book it for a month.”

— Tony Visconti

As Visconti recalls. “He was faster than lightning. He was such a quick worker that he would declare the take was good, and the band would often complain, Bill in particular, that they’d only just learnt the song and they could do it better. If Bill said he thought he’d made a mistake, Marc would say not to worry, he’d dub a loud guitar part over it.”

Visconti laughs. “He would rather deal with things in that way, in his determination to get the songs down quickly. He would rather fix a mistake in the recording than scrap the track and start again.

“He was also motivated by the fact that when we were recording The Slider, Marc was paying the bills, and it’s perhaps not fair to call him a cheapskate, but he followed his own budget very carefully. At the studio, he had booked three days to get 18 songs done, whereas Bowie would book it for a month. The important thing for David was to record slowly, in comfort and in style. Marc was just crazy about getting as many tracks recorded in as little time as possible.”

Bolan is often overlooked or underrated in the pantheon of guitar gods, no doubt because the baggage of teen idol and pop superstar don’t sit well with the serious muso leanings of the rock cognoscenti. Bolan could rip out Hendrix-like solos back in his supposed folkie days — see for example a track like “King of the Rumbling Spires” or “Is It Love,” which both predated his chart stardom.

And he could quote classic rockabilly and blues licks on tracks like “Elemental Child” and “I Love To Boogie.” Bolan was totally hip to ’50s rock and roll, citing James Burton as an influence, name checking Alan Freed in his lyrics and copping the riff from Howlin’ Wolf’s “You’ll Be Mine” for his number one hit, “Jeepster.” Bolan even spent a weekend at Eric Clapton’s house watching him play and picking up tips.

As fast as he was laying the tracks down, it was never at the expense of a great guitar tone.

He’d spend a lot of time tweaking sounds. He had a few pedals, not many — a treble booster and a slapback delay pedal — and he knew how to use them.”

— Tony Visconti

“He’d spend a lot of time tweaking sounds,” Visconti says. “He had a few pedals, not many — a treble booster and a slapback delay pedal — and he knew how to use them. He would tweak his sound and his tone, song by song.

“In terms of amps, in the Tyrannosaurus Rex days he’d be using something small, but by the time of The Slider, he’d be using Hi-Watts or whatever he was using onstage – his full stage stack. He was really good at finding the perfect tone, and if I sometimes suggested something to him he’d try it and be open and receptive to my suggestions.”

Bolan treated recording almost as a live event, even wearing his stage clothes in the studio and cranking the amps up.

“Oh my god, he was loud in the studio. It was deafening!” Visconti recalls with a laugh. “Sometimes I’d put on a pair of headphones to cut the sound down so I could be in the studio when he was playing, but he cranked it all up. His rock sound was hard and edgy and loud.”

As fiercely committed to his own vision as he was, Bolan was not dictatorial when it came to the recording process.

“He would always take input from the band. He didn’t write Steve’s bass parts and he didn’t tell Bill what to play. Mickey was a self-starter; he had a few beats. Marc might make a suggestion about what they played or the tempo or whatever, but usually he was very happy to accept what the guys came up with.

“With Marc’s songwriting, everybody knew when the verse or chorus was coming and where you might need a drum fill or something. Bill was like a pop music master — one of the best drummers that I ever worked with.

“However, when Steve Peregrine-Took said to Marc that he wanted Tyrannosaurus Rex to record his own songs as well, that was the end of Steve. He was just fired immediately. I think the band knew this, so there was no point in saying that they had some songs they’d like him to try.”

When Steve Peregrine-Took said to Marc that he wanted Tyrannosaurus Rex to record his own songs as well, that was the end of Steve. He was just fired immediately.”

— Tony Visconti

In Bolan’s incredible run of hit singles, there are several songs that particularly stand out: “Telegram Sam,” with its chugging, Chuck Berry–like rhythm guitar stabs and lyrics that reference Dylan; “20th Century Boy,” perhaps the hardest rocking of the singles; and “Hot Love,” which has a wordless chanting refrain that lasts longer than the main body of the song, coming in at five minutes of hypnotic grooving. This was no happy jamming accident.

“That was deliberate,” Visconti notes. “We intended it to run that way. We thought it was great and we made sure that we kept it interesting as it repeated itself. Flo and Eddie [the singing duo Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, formerly of the Turtles] were having a ball, screaming and keeping the excitement level up. It was certainly not boring. I think there was an edited version with an early fade out for DJs who didn’t have the time to play the full version.”

As the hits started to dry up, Bolan seemed to lose direction on both a musical and a personal front. He gained weight, and his music similarly became weighed down with endless attempts to channel a little funk or R&B, with female backing singers swamping the tracks. Bolan was losing the vibrancy and essence of the soul of rock and roll, which he’d epitomized since 1970. Enter punk rock in 1976. The punk litmus test created a “year zero” slash-and-burn evisceration of all the music that had gone before, with the notable exceptions of certain artists, Bolan being one of them, who were credited as major influencers on the movement.

Of course it was largely a pose, with all the major players later admitting that they loved the classic rock dinosaurs. Even Johnny Rotten claimed to like Pink Floyd. This new, febrile atmosphere energized Bolan. Thus by 1977, with a revitalized, slimmed-down look, hip haircut and weekly TV pop show, (which featured, incidentally, many of the key punk acts), he became the de facto godfather of punk.

Bolan even took the Damned out on tour with him in 1977, cannily drawing to his live shows, not only his old fans, but also the younger, newly minted punk generation who’d missed out first time. Dandy in the Underworld, arguably his best album in several years, was receiving positive reviews.

He seemed to be on the cusp of a return to his former glory when tragedy struck. Bolan was killed in a car crash, on September 16 of that year, while riding in the passenger seat of the car driven by his partner, Gloria Jones. He was only 29 years old.

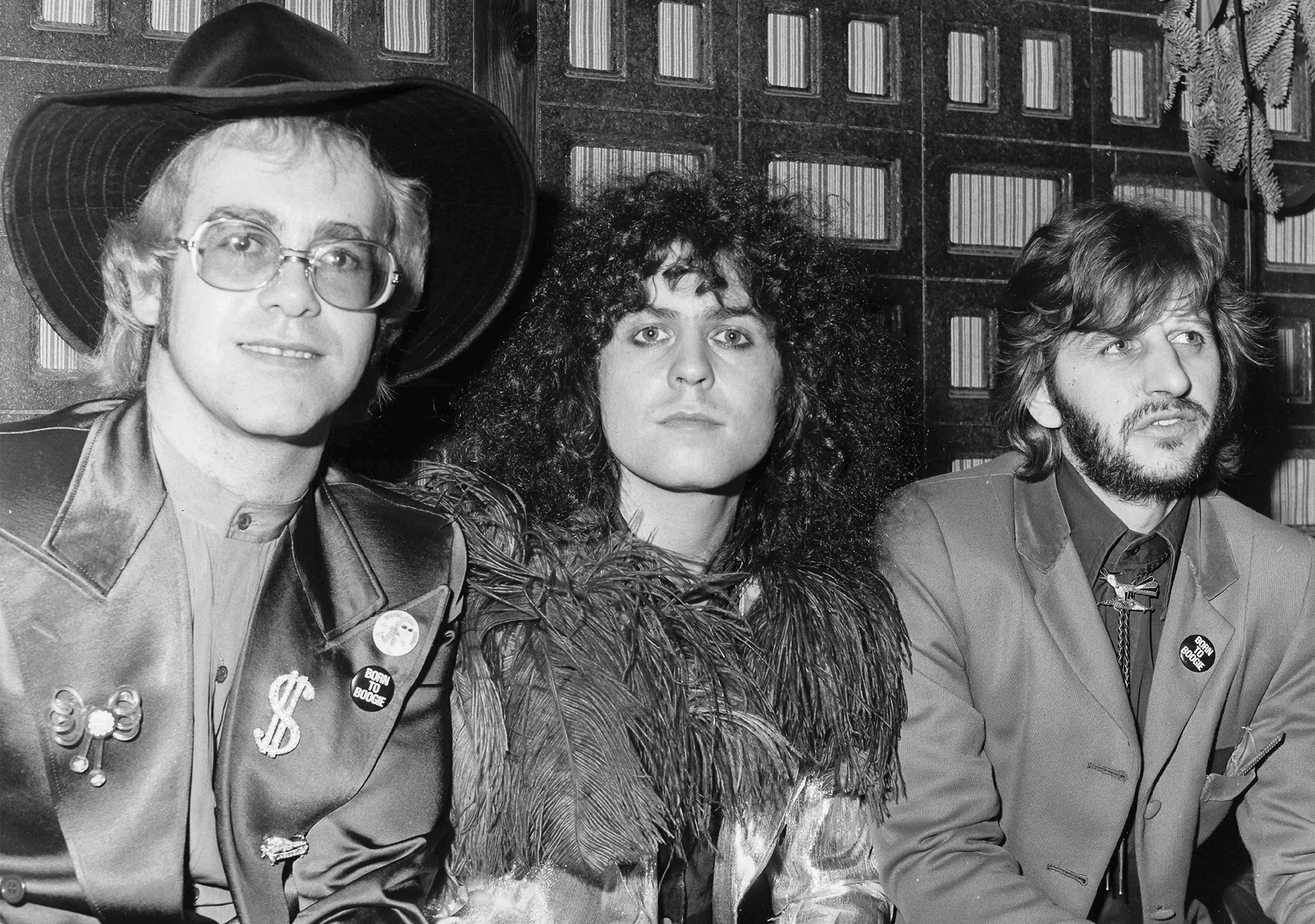

For mainstream American audiences, Bolan remains something of a cult figure. America never replicated the scenes of hysteria, audiences of girls screaming louder than the music, the media intrusion into every aspect of his life which was accorded to Bolan by the rest of the world. Ringo Starr was not only a huge fan of Bolan but also a personal friend. Both Starr and Paul McCartney commented at the time that they wondered if the adulation for Bolan in the U.K. even exceeded that of the Beatles themselves.

As for why Bolan’s success didn’t translate into a wider American audience, it was undoubtedly a case of too much too soon, to borrow an album title from a band who were heavily influenced by Bolan, the New York Dolls. Had MTV been in existence, Bolan would have been filling football stadiums.

Whereas many artists’ songs are frequently covered and re-interpreted, Bolan’s work has never really received the same treatment. This is largely due to the fact that Bolan so completely inhabits every T.Rex song. His lyrics — often derided as inane nursery rhymes — are so completely in accord with the image, the voice and his unique guitar style. His distinctive vibrato on his solos perfectly matches the vibrato in his voice, ensuring that no cover could ever come close to the original.

Visconti agrees.

“I’m not a fan of anybody’s covers,” the producer says. “I would absolutely agree that Marc made the definitive versions of his songs, and it is really hard to better that or do something different. I’ve never heard a real good cover of Marc.”

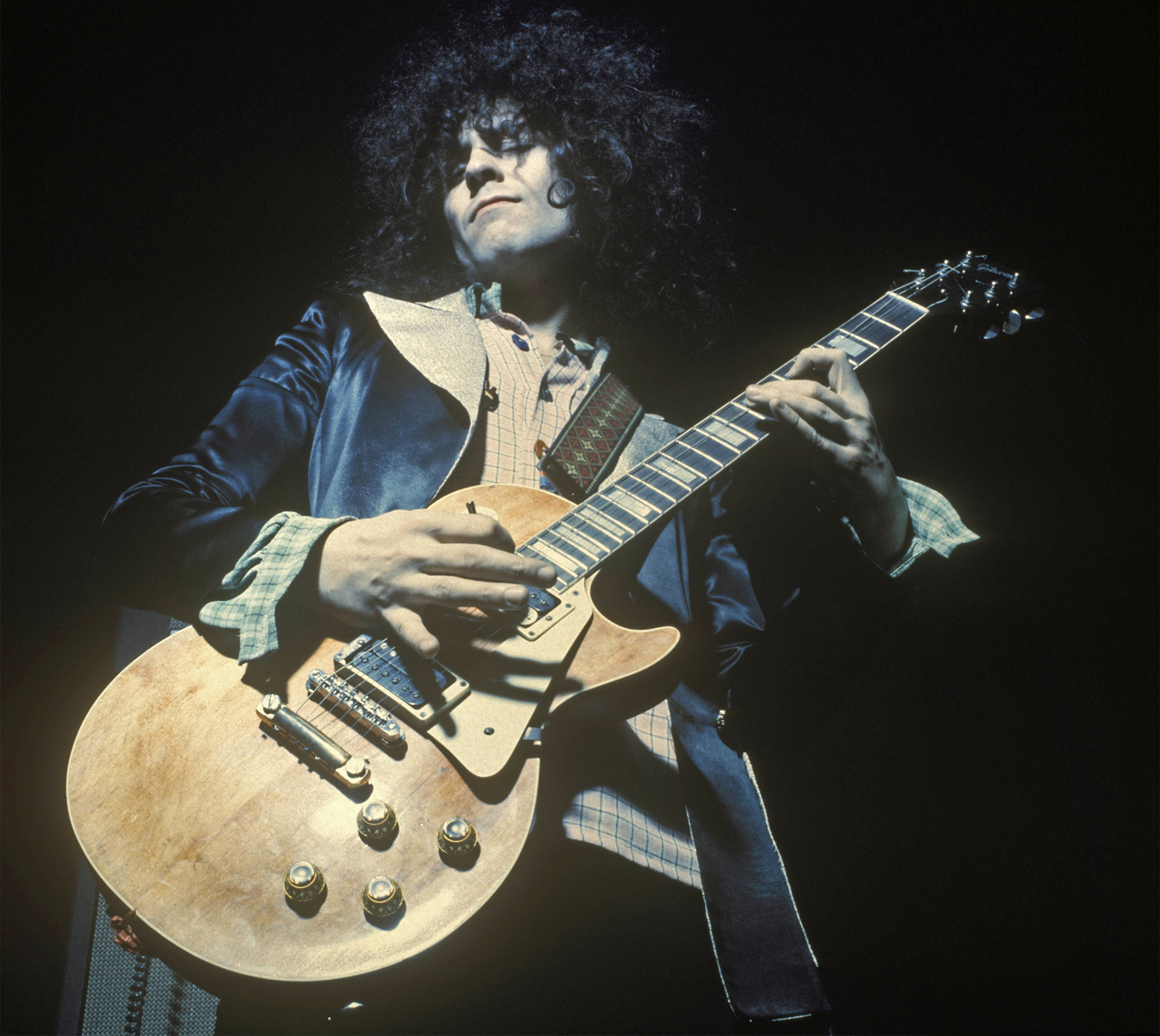

Bolan is remembered as the creator of glam rock, but he was so much more than that. Unlike Bowie, Bolan never hid behind characters, or felt the need to reinvent himself. He was 100 percent Marc Bolan, the electric warrior. A poet, an icon and a hell of a great guitarist, with his low-slung Les Paul (Marc knew what rock and roll was supposed to look like, as well as sound like) and his patented Bolan boogie rhythm electric guitar style, with the subtle pulling and pushing of the beat that was his distinctive sonic signature, Marc Bolan is long overdue for recognition.

If you still need convincing, check out “Bang a Gong” and see if you can keep your feet still and the smile off your face.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.