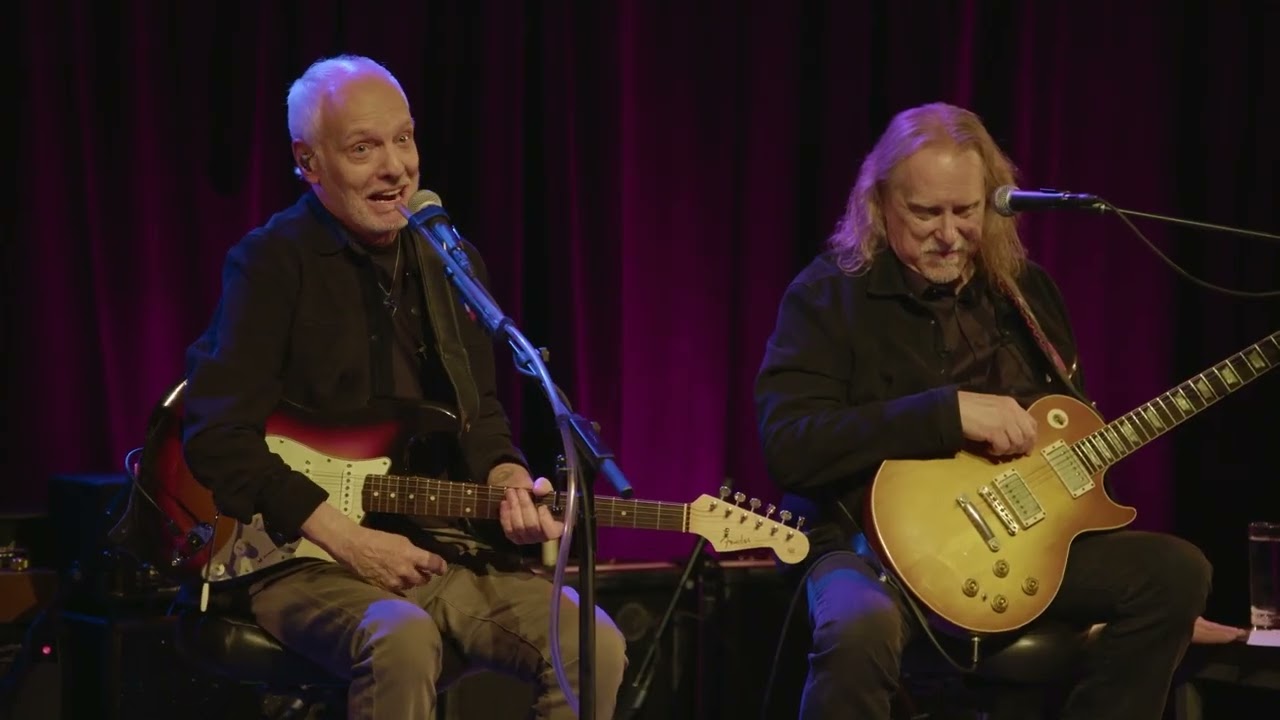

“When they told me it was the biggest record ever, I got scared.” Peter Frampton tells Warren Haynes about the “very difficult period” brought about by the monster success of ‘Frampton Comes Alive!’

The guitarist dives deep into his career in an interview and performance with Haynes for the new TV series ‘The Art of Music,’ premiering September 6

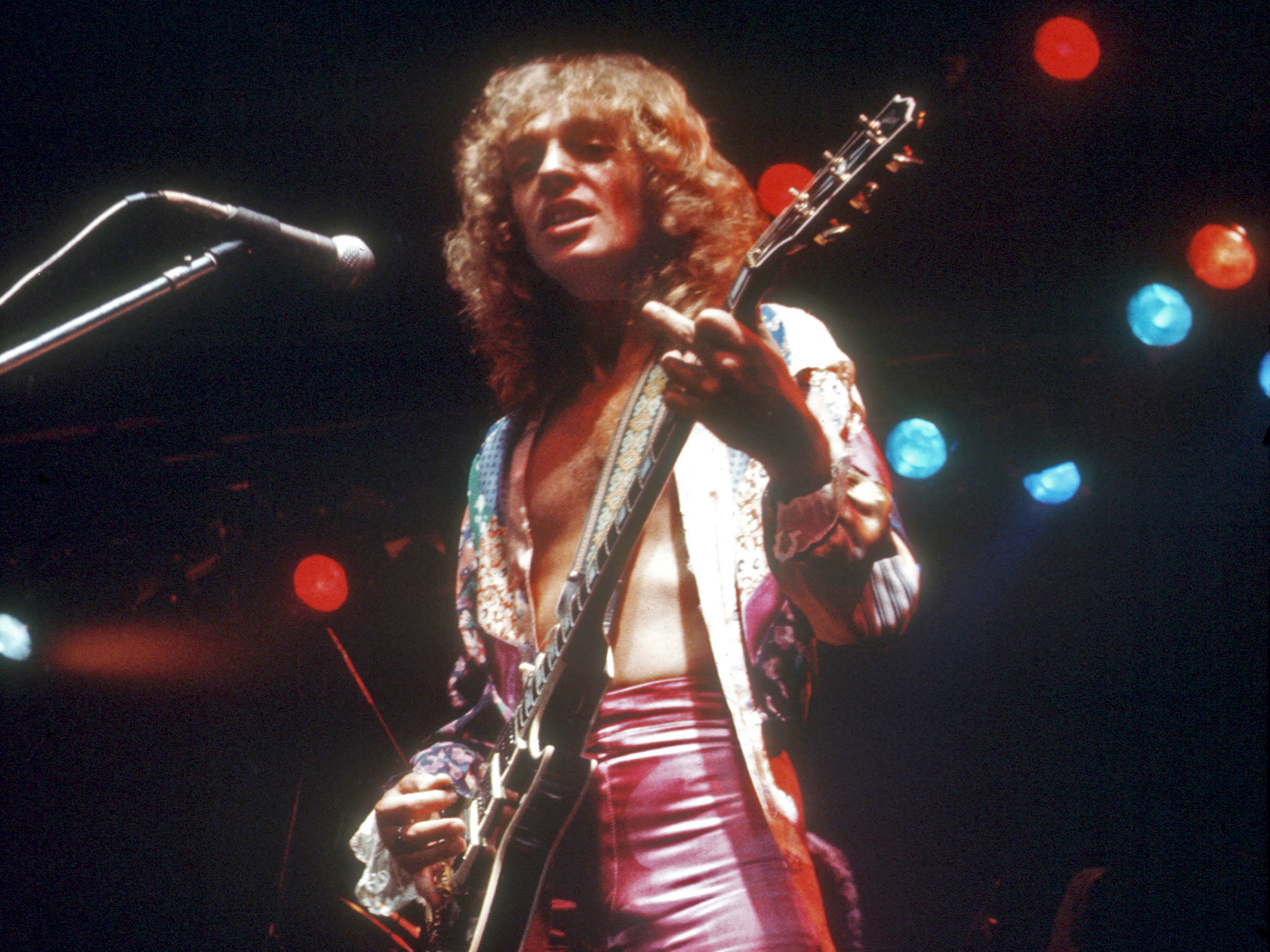

In 1976, no musical artist was bigger than Peter Frampton. His live double-album Frampton Comes Alive! was at the top of the charts and went on to become the year’s biggest seller, with its songs in constant rotation on the radio.

But as Frampton reveals in the new public television series The Art of Music, behind the scenes he was struggling with his newfound fame and the question that dogs every artist who creates a culture-shifting moment: What’s next?

“When they told me it was the biggest record ever, I got scared,” Frampton tells his interviewer, guitarist Warren Haynes. “Because you know that you've got to follow it up.”

Frampton’s revelation is one of many discussions the guitar icon has with Haynes in The Art of Music, which premieres September 6. Filmed before an audience at New York CIty’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the show combines interviews with music performances, as Haynes leads Frampton through a conversation about his musical journey and creative processes.

Frampton’s 1976 rise to superstardom is among the many topics discussed, revealing his emotional vulnerability at a time when he was at his commercial peak. As Haynes notes, Frampton Comes Alive! was a seismic event in American music, one that reverberated well beyond the album’s initial release. The album remains one of the top-selling live records of all time, with more than 17 million copies sold worldwide.

“In 1976, it was the biggest-selling record in America,” Haynes says. “But in 1977, it was still the 14th biggest-selling record in America. That's amazing.

“So now we’re back to that question of what happens when you do this?” he asks, raising his hand. “Like, your career just went skyrocketing.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Frampton doesn’t miss a beat.

“What goes up….” he deadpans, drawing laughter from the audience.

The rocket analogy is appropriate. As the guitarist explains, Frampton Comes Alive! was the culmination of all the work he had done both solo and with Humble Pie, the British blues-rock group he formed in 1969 with former Small Faces singer/guitarist Steve Marriott. After years of working to build an audience, Humble Pie had a bona fide hit with Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore, the live 1971 album containing their hit version of “I Don’t Need No Doctor.”

But Frampton exited the band before its release to launch his solo career. Over the next four years he put out a quartet of albums, building momentum with tunes like “Lines on My Face” and “Do You Feel Like We Do?”

Then came Frampton Comes Alive!, a live double-LP document of the tour for his 1975 studio album, Frampton, which contained the songs “Baby, I Love Your Way” and “Show Me the Way.” Both tunes, as well as “Do You Feel Like We Do?,” became monster hits when they were released as singles from Frampton Comes Alive! Their success helped propel the album to the top of the charts, where it spent 10 nonconsecutive weeks from April through October of 1976.

You're only as good as your last record, and I should not never have made any other records.”

— Peter Frampton

But while the album made Frampton a global star and established him as one of the 1970s’ top performers, privately he was rattled by his sudden ascension.

“First of all,” he explains in The Art of Music, “it had taken me six years to write all that material, culled from Humble Pie, from all my solo records up to that point — and a cover,” he adds, referring to his live version of the Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.”

“So, yeah, it was a very difficult period for me, especially when they told me that I was not only number one in the charts but that I'd sold more than Carol King's Tapestry, which was the top-selling record ever at that point.”

But while teens grooved to his music and lined their bedroom walls with posters of the album’s cover — featuring Frampton playing his celebrated Gibson Les Paul Custom electric guitar — he fretted over his next move.

“You're only as good as your last record, and I should not never have made any other records,” he tells Haynes. “I should have just [said], ‘That's it!’

“But there's nothing better than having the biggest record in the world, I guess,” he adds with a wry laugh.

Haynes — who has had his own share of career transitions between his time with Dickey Betts, the Allman Brothers Band and Gov’t Mule — certainly knows a thing about riding music’s unpredictable waves. It undoubtedly informs his followup question.

“Did you feel like you had to rethink everything from that point?” he asks. “Like, take some time and figure out what’s going to be next?”

As Frampton explains, he did reach that point, but not until after he’d released his next album, 1977’s I’m in You, almost a year and a half later. It hit number two on the charts to become his most commercially successful album.

But as he reveals in The Art of Music, he was never fond of it.

“After the I’m in You record came out — which I didn't want to make, let alone release — I realized that it was time to take stock, and a lot of things happened there,” he says. “Money was going astray by the hundreds of thousands. And so I needed to sort all that out.

I realized that it was time to take stock. Money was going astray by the hundreds of thousands. And so I needed to sort all that out.”

— Peter Frampton

“And that's when I sort of stopped working and basically just started writing on my own and getting ready for something that was to come.”

Frampton credits his long career to his resilience in the face of adversity. And he's continued to demonstrate it in his 10-year fight with Inclusion Body Myositis (IBM), a degenerative order that weakens muscles.

“I’ve always been knocked down,” he says, “and then you take a second or two, and if you don't go to 10, you're okay. You get up on nine, and then you start again. And it's never too late to start again.”

In addition to the great and informative discussion, The Art of Music features Frampton and Haynes performing live, with assistance from bass guitar player Alison Prestwood and keyboardist/musical director Rob Arthur on “Baby, I Love Your Way,” “Lines on My Face” and “Do You Feel Like We Do,” shown below.

Created and executive produced by iMaggination’s Don Maggi, The Art of Music was developed to give viewers a rare look inside musical artists’ lives and their creative practice before an invited audience at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Frampton’s episode will air on public television stations nationwide beginning September 6, 2025. Viewers can also stream it on the PBS app and watch it on the Art of Music website, where additional artists in the series will be announced.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.