"It hit me like a ton of bricks: I’m playing live with Pink Floyd and trading licks with David Gilmour!” From jamming with Gilmour to getting guitar lessons from the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards — one guitarist has lived out every player’s fantasies

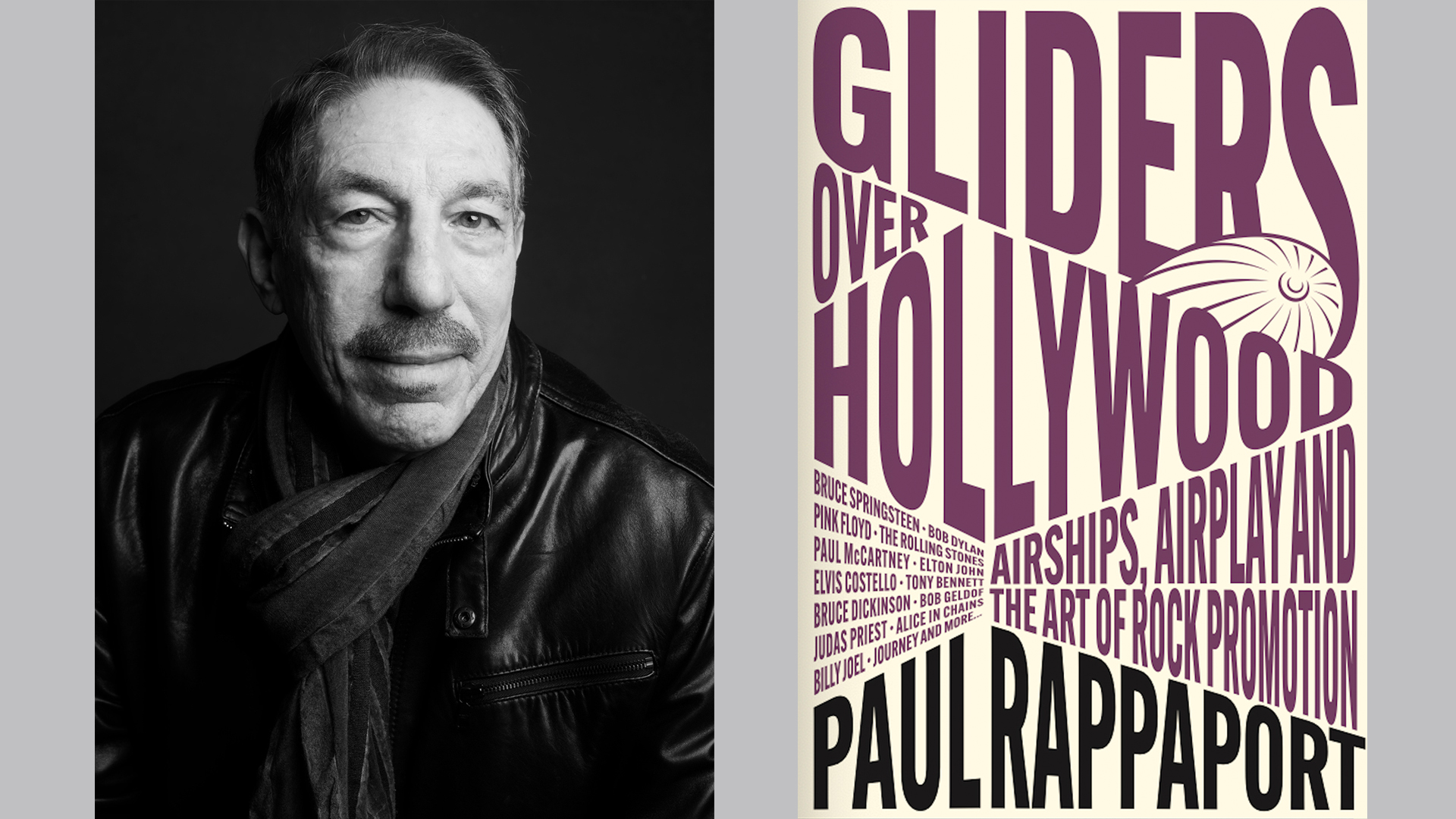

Former record exec Paul Rappaport recounts his adventures with Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen and other rock legends in his new memoir, ‘Gliders Over Hollywood’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Being a big-time record company executive certainly comes with perks. And some of Paul Rappaport’s most treasured bonuses were of the six-string variety.

Rappaport spent an appropriate 33 1/3 years working in radio promotion for Columbia Records, ascending to the role of senior vice president of rock promotion and working with a who’s-who roster of artists that included the Rolling Stones (individually and collectively), Paul McCartney, Pink Floyd and a score of others.

He also help launch the careers of Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Blue Öyster Cult, Loverboy and Alice in Chains. He went on to win an Emmy Award for Live by Request, a performance series he created for the A&E Network that ran from 1996 to 2004, and pen the popular blog Backstage Access. He chronicles all of this in a new memoir, Gliders Over Hollywood: Airships, Airplay and the Art of Rock Promotion, from Jawbone Press. (The title refers to a promotion for Aerosmith’s debut album.)

Rappaport is also a player from his youth, first inspired by the regional Country Music Time morning TV show broadcast to his hometown of Los Angeles.

“As I watched the performers, I was immediately entranced by the guitars they played,” Rappaport — also a master magician and fencer — writes. “Most striking to me was that each guitar seemed to have its own soul. When the player hit the strings, a unique voice would ring out helping to bring the singer’s songs to life. The attraction was so strong I told my parents I needed to learn how to play guitar.”

He did just that, taking lessons at a local music shop and learning to play Spanish and Hawaiian styles, country and folk before rock and roll.

Rappaport played in a variety of bands (the late Karen Carpenter was a classmate at Downey High School) and saw early shows by the Stones, the Jimi Hendrix Experience and others before attending UCLA and joining Columbia as a college rep before taking on a full-time job with the label after graduation. There was always a guitar close by, however.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I love to play,” he tells Guitar Player via Zoom, in an office that has a 1959 Les Paul reissue visible in the background amidst gold and Platinum record plaques and other memorabilia. He also has a 1952 Les Paul goldtop reissue and a 1962 Les Paul Junior that he received as a gift.

“I’m a Les Paul guy,” he notes. “I like the sound, that real creamy, dreamy tone you get from them.”

Other models, however, account for some of Rappaport’s best guitar stories in Gliders Over Hollywood.

Arming Elvis Costello’s Forces

“I don’t part with a lot of guitars; they become your friends,” he notes. But one he gave away was a 1967 red Rickenbacker with an F-hole and sharp body edges — to Elvis Costello.

“I loved Roger McGuinn and the Byrds and that 12-string Rickenbacker sound,” Rappaport says. “But I bought the six-string because I was playing in a band and I needed something more versatile. Still got the jingle-jangly sound, but I could play any style of music with it.”

While squiring Costello and his Attractions on their first U.S. tour, Rappaport learned that Costello also loved the Rick sound and wanted to buy one, but was having a hard time finding one with its original pickups intact. Rappaport had at the time switched to a Gibson Melody Maker as his main axe and was not playing his Rick much, “so I told Elvis I’d give him my Rickenbacker.

“I was such a fan of Elvis’s music,” he recalls. “People had given me guitars. The Melody Maker was given to me by one of my best friends in life, from my high school band. As a musician, there was this little voice inside that said, I think I’m supposed to give one back.

“Elvis said, ‘At least let me buy it from you.’ I said, ‘Y’know, El, we’re becoming friends. It would mean more to give it to you. It feels natural to give it to you.’ A guitar needs to be played, right? Not sleeping like a princess under my bed.

“Then he goes off and uses it all over Armed Forces. I was jumping up and down: ‘My Rickenbacker is famous!’ It was in good hands. It did what it needed to do. So I never looked back.

“Sometimes I think, ‘Does he still have it? Would he give it back?’ But I don’t need it now for the kind of music I play. I’m just glad it went on to the next life it was meant to have.”

Running Like Hell with Pink Floyd

Rappaport became friendly with Pink Floyd when the band signed with Columbia during the early ’70s and worked on campaigns for Wish You Were Here, Animals, The Wall and The Final Cut, as well as the members’ solo albums.

After helping the band navigate its difficult comeback, sans Roger Waters, with 1987’s quadruple-Platinum A Momentary Lapse of Reason, Floyd manager Steve O’Rourke contacted Rappaport later in the year, telling him the band wanted to give him a special Christmas present as a thank-you for his efforts.

Rappaport waved it off, but early in the new year O’Rourke called back with an offer to join the band onstage during its summer tour — a gesture inspired by Rappaport’s assistant, who had told the manager about his dream to play live at a massive venue

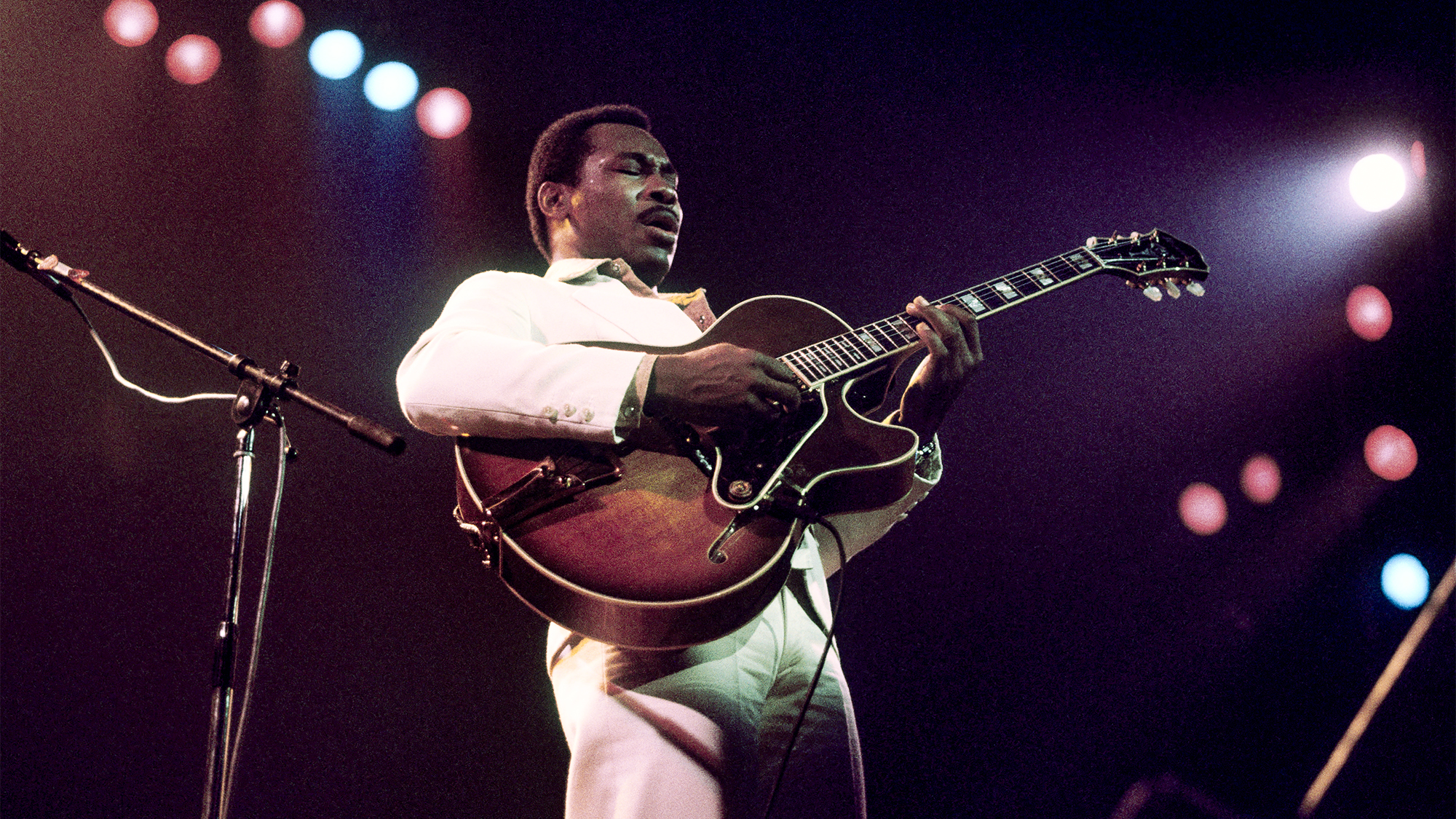

Rappaport chose an August show at London’s Wembley Stadium and flew across the pond for what he describes as “a full rock-star treatment” from before the gig through the after-party. He spent three months learning “Run Like Hell,” the show’s final song, even studying its nuances with the guitarist from a local Pink Floyd tribute band.

“I was a real player, so I wanted to be serious about it, not like... a lark,” he says.

David Gilmour offered Rappaport one of his Fender Telecasters, but the exec instead chose one he brought with him from the States because he preferred the lighter-gauge strings. Gilmour also instructed Rappaport to leave the soft chords from the recording alone and concentrate on the major and power chords the group favored in live performance.

Rather than a blur, Rappaport recalls everything from the sound check to his conversations with Gilmour’s guitar tech Phil Taylor and the actual performance.

“I was already in a euphoric state and then things got even better,” he recalls. “In the middle of a song, after a trippy Richard Wright keyboard solo... David played a lick, then turned around and motioned with his finger for me to answer. Instinctively, I did, and the next thing I knew we were trading licks.

“All of a sudden it hit me like a ton of bricks: Let me get this straight; I am in Wembley, playing live onstage with Pink Floyd, and I’m trading licks with David Gilmour. Is that what the fuck’s happening?”

I threw my pick into the audience and waved my hand. For just a little over seven minutes, I was in Pink Floyd — for real.”

— Paul Rappaport

Gilmour and drummer Nick Mason brought Rappaport to the front of the stage to take the final bow with the band.

“I felt like I’d played well, and now I could finally take in all the applause and hoopla happening around me. I took a bow standing next to David and Nick, threw my pick into the audience and waved my hand. ‘See ya next time!’ What a fucking blast.

“The band’s other keyboardist, Jon Carin, walked by and gave me a thumbs-up and a smile. That meant so much to me — like I was on par with the gang. And, for just a little over seven minutes, I was. I was in Pink Floyd — for real.”

Rappaport never repeated the guest spot with Pink Floyd but did continue to work with the band, including a campaign to announce its 1994 album, The Division Bell, and the accompanying tour with a seven-figure blimp blitz that traveled around the country.

"5 Strings, 3 Notes, 2 Fingers..." and Keith Richards

Rappaport says that in doing his job, “It meant a lot to me to help these artists, who were heroes of mine. My life was shaped by them... It was one of the joys for me that I could give back to them, ’cause I grew up with these people.”

And it was particularly resonant to meet, become friendly and ultimately get to play guitar with Keith Richards.

“I was a Rolling Stones nut,” he says. “I learned to play electric guitar listening to those early Stones records, listening to Keith Richards, so I really wanted to do something good for those guys because I love them. And it meant a lot to me to have a relationship with Keith Richards. The guy’s my idol.

“And then all of a sudden I’m getting a guitar lesson from this guy. How cool is that?”

That occurred during the video shoot for the Stones’ 1986 rendition of Bob & Earl’s “Harlem Shuffle” for the group’s Dirty Work album. Rappaport had gotten to know Richards during the New Barbarians tour a few years earlier (Stones mate Ronnie Wood’s Gimme Some Neck came out on Columbia in 1979), but found a more lucid musician and man at the Midtown Manhattan soundstage — where Richards even apologized for anything he did years earlier that might have offended Rappaport.

Rappaport used the opportunity to “gush on” Richards. “We were now just two guys talking guitar,” Rappaport writes. Richards explained why Rappaport’s attempts to cover Stones songs with his teenage bands failed, telling him about the G tuning he learned from Don Everly. He instructed Rappaport to go home, remove the bottom E string from his guitar, then tune the A string to G and the top E to D.

Further instructions: “Bar any fret you like, play an open chord, and add your second finger one fret up on the B string, your third (finger) two frets up on the D string, hammer on and off, then report back.”

When I came back to the video shoot the next day, I don’t know who had the bigger smile on his face, me or Keith.”

— Paul Rappaport

It was a lesson well-learned, as “all of those Rolling Stones hits start(ed) falling effortlessly out of the guitar... When I came back to the video shoot the next day, I don’t know who had the bigger smile on his face, me or Keith.”

Rappaport would go on to have even greater success for the Stones with 1989’s Steel Wheels album, scoring three number one Billboard Mainstream Rock chart hits with “Mixed Emotions,” “Rock and a Hard Place” and “Almost Hear You Sigh.” The album also went top five and double Platinum.

Though the group would move to another label after that, he subsequently sent Richards a photo Henry Diltz had taken of the guitarist, warming up in a dressing room. It was signed, “To Paul, 6 strings, 3 notes, 2 fingers, 1 asshole — Love, Keith.” Rappaport keeps it in view in front of him in his home office.

Gliders Over Hollywood: Airships, Airplay and the Art of Rock Promotion, by Paul Rappaport, is out now from Jawbone Press.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.