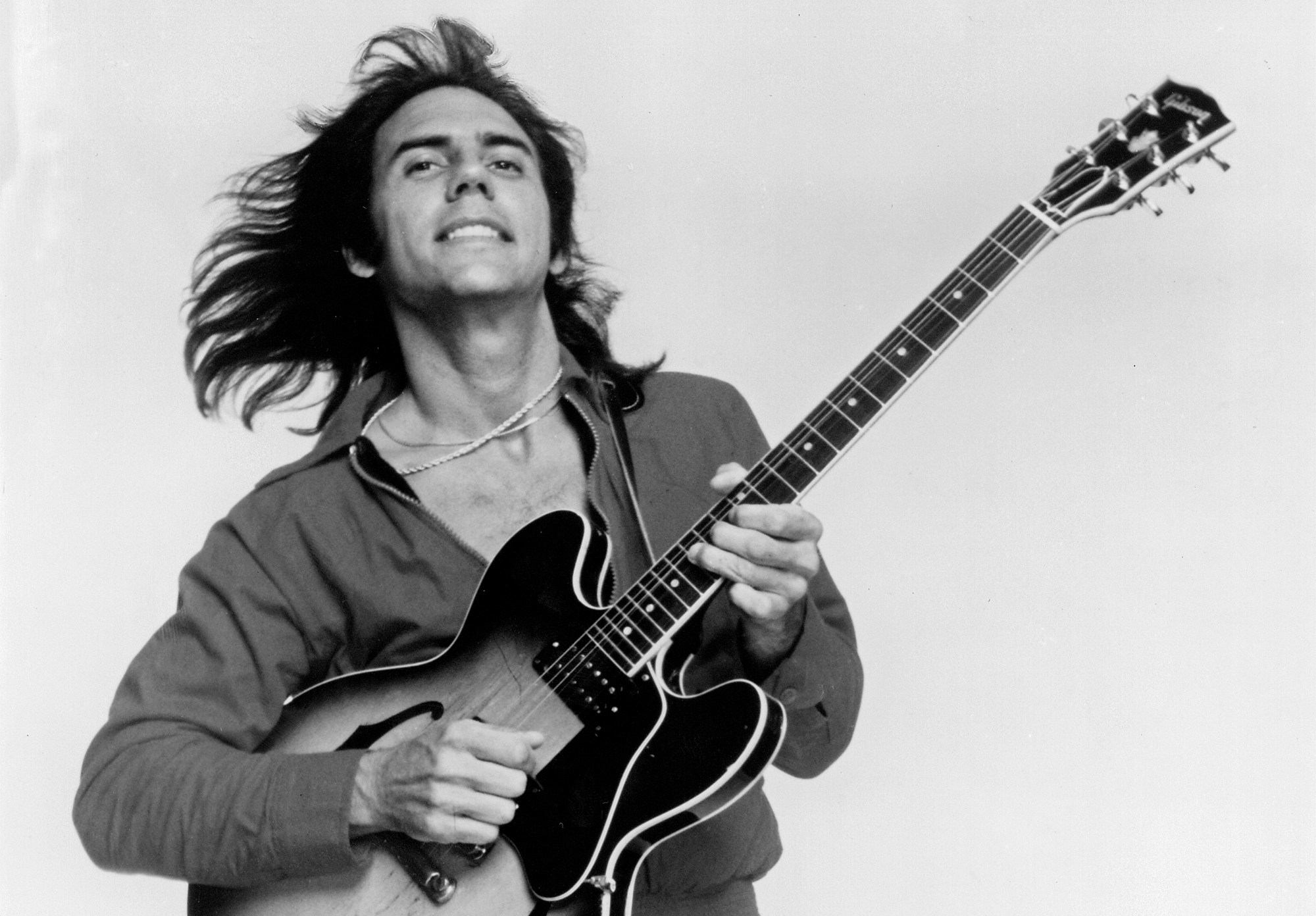

"It was a bad time for him." John Lennon's sessions for a classic solo album were chaos. Larry Carlton reveals what made him quit after just one day

He's often credited with performing on the album, but Carlton says his work never made the final cut

When it comes to recording with an ex-Beatle, there’s never been a shortage of takers for the gig — and who could blame them? In the early 1970s, playing on a John Lennon record wasn’t just a cool credit — it was the musical equivalent of a golden ticket.

However, as Larry Carlton reveals in a new interview, a studio session with one of music’s biggest names could turn out to be a real “drag.”

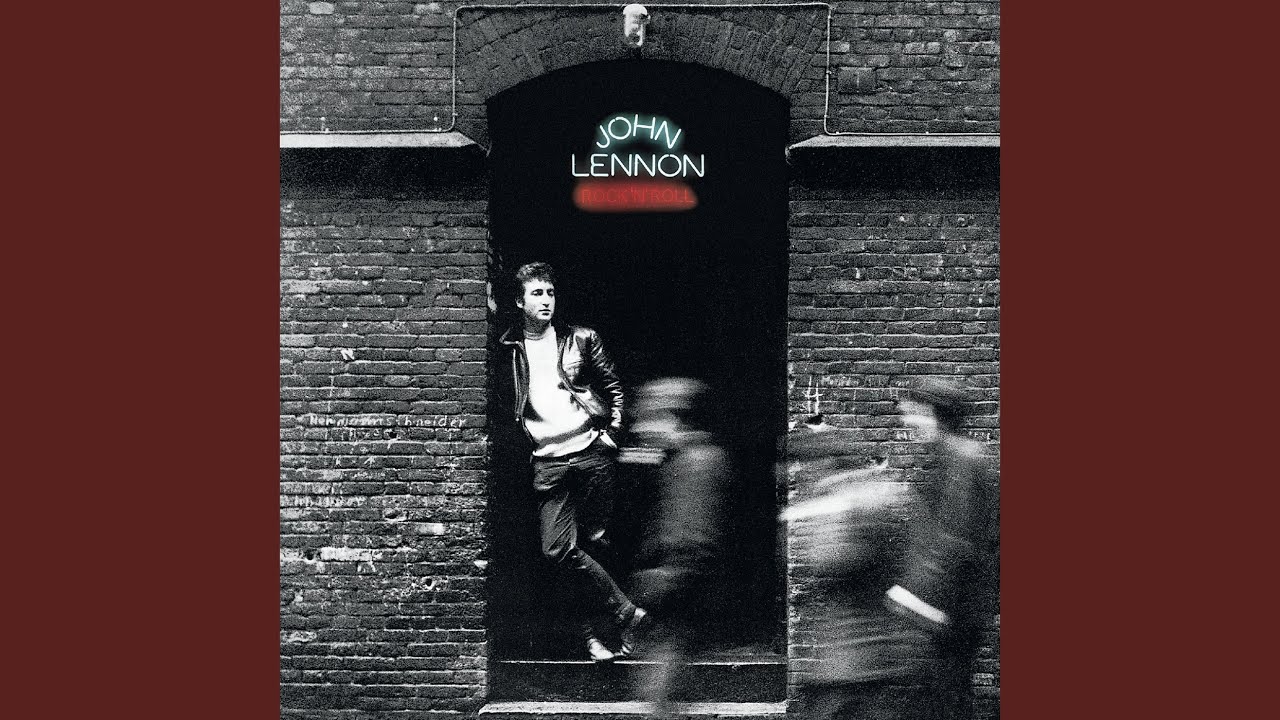

The session in question was for Lennon’s Rock ’n’ Roll, a mid-’70s covers vehicle. But to tell the story properly, we need to head back to 1969, when music publisher Morris Levy accused Lennon of lifting lyrics from Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me” for the Beatles’ Abbey Road cut “Come Together.”

Levy sued, and after years of legal back-and-forth, they settled out of court. (Interestingly, Berry himself never seemed all that bothered and even made an appearance with Lennon in 1972 on the syndicated Mike Douglas Show.) Lennon’s deal with Levy required him to record a few songs from Levy’s publishing catalog. Lennon was only supposed to knock out a few covers and call it a day, but he instead used it as an excuse to make an entire album of the rock and roll classics he’d grown up on.

He called his old buddy Phil Spector — who, as far as Lennon was concerned, had done a bang-up job on Let It Be and his 1971 solo opus, Imagine — to rally the musical troops and produce the sessions. It was all great on paper. But it quickly went to hell once the studio doors closed.

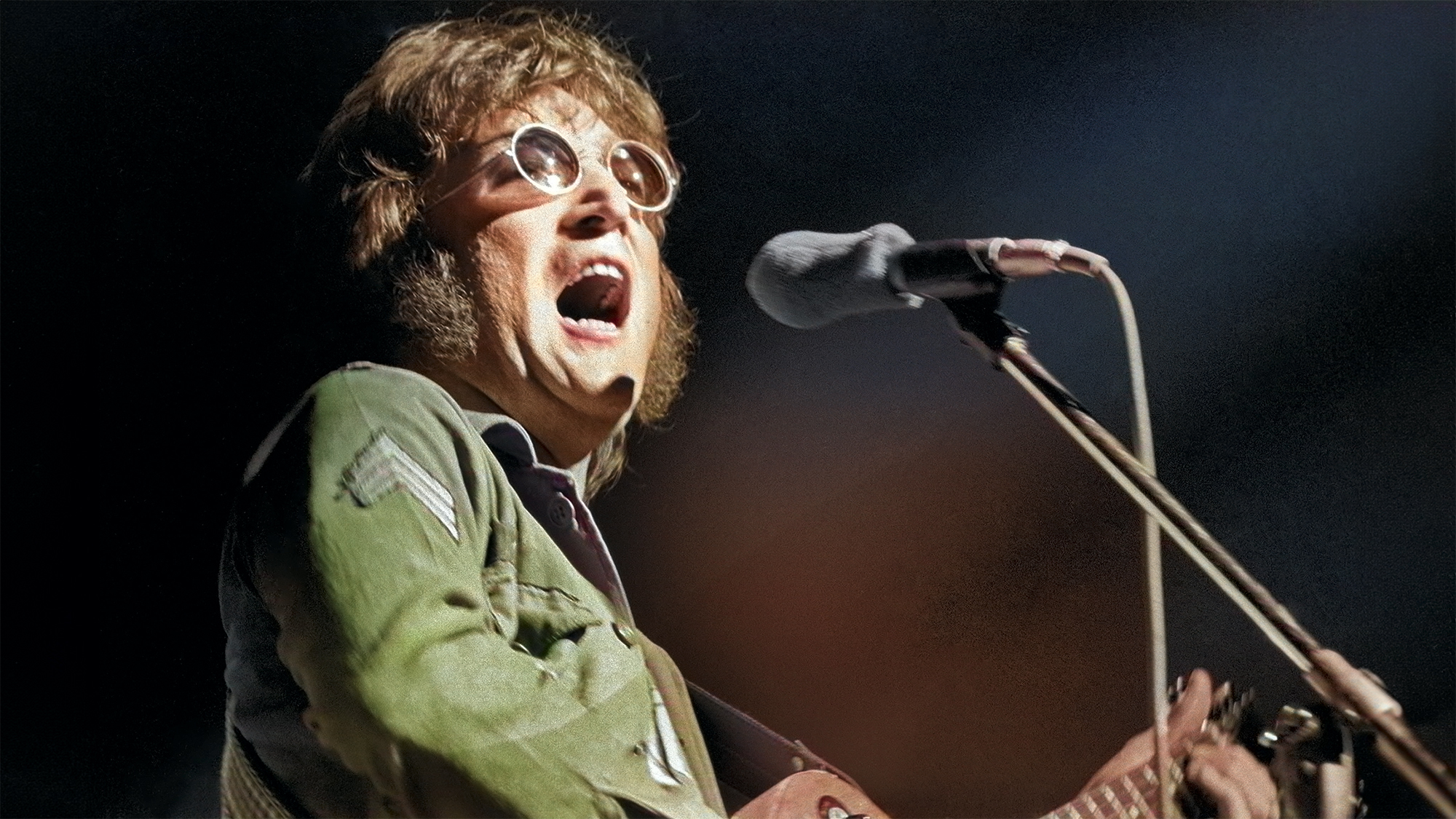

The Rock ’n’ Roll recordings took place sporadically from 1973 to early 1975, with the album dropping in February of that year. From day one, the sessions were unruly. Lennon, newly split from his wife, Yoko Ono, was in the throes of his “Lost Weekend” out in L.A., running wild with Harry Nilsson and the Hollywood Vampires. Spector was largely calling the shots, and allegedly fired a few — but more on that later.

Of all the bad habits on display, Spector, never shy on eccentricity, developed a new, soon-to-be infamous one: At the end of each night, he’d slip out the door with the master tapes under his arm, like a villain in a heist movie.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It was somewhere in the midst of these sessions that Larry Carlton found himself called to A&M Studios for a week's work on the album. Armed with his signature Gibson ’69 ES-335 electric guitar, the 26-year-old player was a major name in the session world, having cut tracks with the Partridge Family, Linda Ronstadt, Vikki Carr, Tom Scott and Andy Williams, and even turning up on TV and film scores. He was also a key part of Quincy Jones’ massive orchestral pop and jazz productions of the era.

In short, if you needed a guitar part in L.A., you were probably calling Larry Carlton. His reputation was built on always delivering, sometimes on a literal moment’s notice, and always with total professionalism. And that was what he expected in return, no matter the star power.

“Phil Spector, the producer, had booked a lot of us musicians for seven o’clock every night that week, five nights,” Carlton remembers. The players arrived. Among them was piano great Leon Russell, who had performed at George Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh.

But seven o’clock came and went. Then eight. Nine-thirty arrived, but there was still no sign of Lennon or Spector.

“Leon Russell and I went into another studio,” Carlton recalls, “and he sat at the piano, and we just kind of jammed a little bit."

By the time Lennon and Spector arrived, around 10 o’clock, the vibe had turned dark.

“It was a bad time for John,” Carlton explains, “He was drinking.”

The song for this night's session was "Bony Moronie," a classic rock and roll hit written and recorded by Larry Williams in 1957.

So John’s calling the chord changes — it’s only three — and he’s going, ‘A, I got a gal named Bony Moronie. D.’ I said, ‘I got it.’ It was a drag.”

— Larry Carlton

“Now, I played ‘Bony Moronie’ when I was 12 years old,” Carlton recalls. “So I’m in my cubby right here, and John’s right here. And he had been drinking. So he’s calling the chord changes — it’s only three — and he’s going, ‘A, I got a gal named Bony Moronie. D.’ I said, ‘I got it.’

“It was a drag. It was. It was not professional and not what I expected.”

When the session came to an end — seemingly not too long after it finally got underway — Carlton ended up driving Leon Russell back to his hotel.

“I said, ‘Man, that was a drag. Darn it,’” he recalls.

“And with his Oklahoma accent, Leon just looked at me and goes, ‘You kidding? I’m back to Tulsa in the morning.’”

Carlton laughs about it now, but at the time it must have felt like a missed opportunity, and a difficult decision to make.

“I got home and called Phil Spector’s office and just left a message at midnight. I said, sorry, I can’t make it the rest of the week. So I cancelled. That wasn’t how I wanted to spend my time. It could have been so cool. But... one of those things, you know?”

By late 1973, Spector had vanished completely, with the tapes in tow. Then, like some kind of Batman villain, he cold-called Lennon to announce, in a sly nod to the Watergate scandal, “I’ve got the John Dean tapes” — and he wasn’t giving them back without a deal.

As if that wasn’t enough, in March ’74 the producer was in a serious car crash that put him in a coma, freezing any hope of making progress on the album or retrieving the tapes. In the meantime, Lennon pivoted to working on a different project that became his 1974 album, Walls and Bridges.

If you’re gonna shoot me, kill me, but don’t mess with my ears, Phil.”

— John Lennon

Meanwhile, record execs at Capitol were tasked with getting the tapes back, and after a drawn-out process, they reportedly shelled out around $90,000 to recover them from Spector.

In the end, nothing about the recording sessions appears to have gone smoothly. Spector was producing, which meant you could expect a wall of sound and some chaos — and that’s exactly what happened. His behavior in the studio became so extreme that there are rumors of him firing a gun in the A&M control room in close proximity to Lennon’s head. Lennon reportedly told him, “If you’re gonna shoot me, kill me, but don’t mess with my ears, Phil.”

So who actually played guitar on the version of “Bony Moronie” that appears on the finished album? For years, even reputable compendiums like The Beatles Bible listed Larry Carlton as a guitarist on the Larry Williams cover. But as Carlton himself said in his new interview on the Thinking About Guitar YouTube channel, he “didn’t end up on the album.” The finished version likely features Steve Cropper and Jesse Ed Davis, considering their handling of the guitar duties in the sessions that followed, but the jury’s still out.

Lennon would eventually finish the album in New York, producing the last sessions himself at Record Plant East. Rock ’n’ Roll was released in February 1975 and stands today as a rowdy time capsule of the man’s musical life at that stage. It would be Lennon’s last true solo album before 1980’s collaborative effort with Yoko Ono, Double Fantasy. Tragically, Lennon was shot and killed outside his and his wife’s apartment at the Dakota, in New York City, just a few weeks after the latter’s release.

Had he lived longer, it’s easy to imagine Lennon and Mr. 335 might have crossed paths in a studio somewhere in the world, but in the end, it’s another one of music’s “what could have been.” Looking back, Carlton stands by his call. “Yeah, that wasn’t fun. I’m an admirer, but that was a bad time.”

The Editor in chief of Guitar Interactive since 2017, Jonathan has written online articles for Guitar World, Guitar Player and Guitar Aficionado over the last decade. He has interviewed hundreds of music's finest, including Slash, Joe Satriani, Kirk Hammett and Steve Vai, to name a few. Jonathan's not a bad player either, occasionally doing gear reviews, session work and online lessons for Lick Library.