“If I chicken out this time, I cop out to myself too.” After quitting John Mayall and Cream, Eric Clapton thought his legendary band would last “a long time.” They fell apart after one album

The guitarist knew he was the reason his previous groups had broken up. This time he planned to make it stick

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

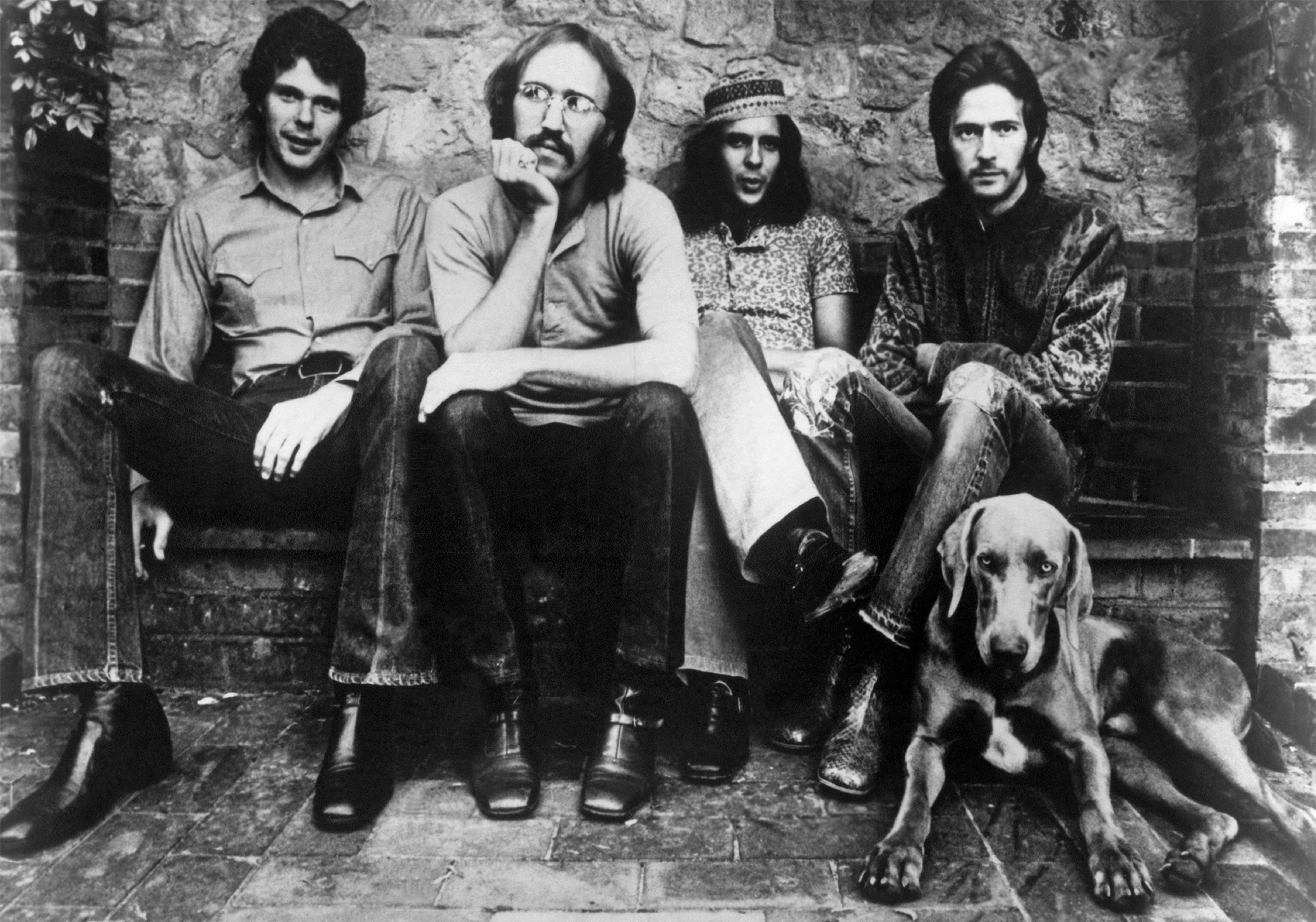

Derek and the Dominos were a blink-and-you’ll-miss-them group. After forming spontaneously in the summer of 1970, the Eric Clapton–led quartet recorded an album, Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs, with assistance on electric and slide guitar from Duane Allman, who was then becoming famous with his group, the Allman Brothers Band. Around the time of the album’s release, on November 9, 1970, the band went on a short U.S. tour, from October through December. On January 6, 1971, they appeared on The Johnny Cash Show, their only TV appearance, where they received an enthusiastic reception from the studio audience.

And then nothing. The band was, in effect, history.

But apparently Clapton had no intentions of letting the group dissolve so quickly. In an October 1970 interview with journalist Howard Smith, the guitarist expressed his dedication to the band, and suggested he saw it as a test of his will to commit to a group after a period of aimless wandering.

At the time, two years had passed since the demise of Cream, the first group to which he shown any devotion. In the interim he’d formed and dissolved Blind Faith and performed as a sideman to Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, with whom he subsequently released his 1970 self-titled album.

But the solo career never took off, and by the summer of 1970, Clapton had formed Derek and the Dominos with three Delaney & Bonnie cohorts: keyboardist and singer Bobby Whitlock, bass guitarist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon.

At the interview’s outset, Smith offers Clapton a list of the bands he’d played with up to that time, including the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and the previously listed acts. Why, Smith wondered, did Clapton leave so many bands in such a short period of time.

“Dissatisfaction, the desire to move on. That's probably the whole thing,” Clapton offered. “The group dissolves. It's a natural thing.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Certainly, Cream was the one act that lasted the longest, from 1966 to 1968. Clapton attributed its demise to a lack of productivity.

“It depends on how powerful and how productive the group is,” he explained. “With a group like Cream, it was very spontaneous but not necessarily very productive. So it didn't last very long.”

But when asked about his then current group, Derek and the Dominos, Clapton had a very different outlook. He anticipated the group being together for quite a while.

“Do you see that lasting a long time?” Smith asked. “Absolutely, yeah,” Clapton answered.

Despite his assurance, and the fact that the group had just completed an album, there were no formal ties holding its members together.

“We still haven't signed a thing,” Clapton admitted. “No one in this group has signed one contract.”

The only times I've ever signed anything on a piece of paper, it's always meant that pretty soon after doing it, I'd get disillusioned,”

— Eric Clapton

The group's integrity, he admitted, was entirely in his hands, not a legal document.

“In fact, I'd shy away from the idea, because the only times I've ever signed anything on a piece of paper, it's always meant that pretty soon after doing it, I'd get disillusioned,” he said. “I mean, so far, the fact that we haven't signed anything has been part of the reason why we stuck together.”

As far as Clapton was concerned, his devotion was the main reason the group would last. He clearly had strong feelings about Derek and the Dominos, going so far as to disguise his role in it to avoid fans from seeing it as an Eric Clapton project.

“I wanted the audiences to accept the fact that it was four musicians rather than me being backed up by other guys,” he told Smith. “Although a lot of the time it does come out like that, because I sing a lot of the lead — in fact, too much of the time. But I still really nourish the idea of the thing being a group instead of one guy with a rhythm section.”

From everything Clapton says in the interview, it sounded like he’d found a home.

“It would have to be a pretty strong reason for this group to break up. Because, you see, most of the times before, it was me that left,” he admitted.

“But this time I can't leave, you see, because I'm at the forefront of the group. I'm responsible, in a way. This is the first time I had a responsible part in any groups I've been in.

“So? I've gotta live up to it. I mean, if I chicken out this time... I cop out to myself too.”

I can't leave, you see, because I'm at the forefront of the group. This is the first time I had a responsible part in any groups I've been in.”

— Eric Clapton

He didn’t chicken out, but neither did he have the strength to endure the hardships that followed. He was devastated by the death of Jimi Hendrix in September, shortly before his interview with Smith. His pain was compounded when, in October 1971, Allman — the guitarist he connected with more closely than any other — died in a motorcycle accident.

Privately, Clapton was nursing his grievance over the reception Layla received upon its release. Although it had favorable reviews in Rolling Stone and The Village Voice, other critics were less kind. Despite just missing the top 10 in the U.S, the album failed to chart at all in the U.K.

In Clapton’s estimation, the album “died a death” upon its release. Many believed it would have done better had he not been so reluctant to put his name on it.

Perhaps he decided they were right. Although the band attempted a second album in mid 1971, the Dominos "broke down halfway through,” Clapton told music critic Robert Palmer, “because of the paranoia and tension. And the band just dissolved."

A few of those later tracks— including "Snake Lake Blues," "Evil," and "One More Chance" — eventually saw release on box sets, including 1988’s Crossroads box set and the 2020 50th anniversary edition of Layla.

But Clapton would never again attempt to form a band. After a year-long seclusion to nurse his wounds and deal with his heroin addiction, he re-emerged with a new devotion: his own solo career. Admitting that he’d wasted the past three years of his life, he got to work re-energizing his love of guitar and the blues with 1974’s 461 Ocean Boulevard. He’s been solo ever since.

But he didn’t leave Derek and the Dominos behind forever. The group and its sole release, Layla, are celebrated as one of the high points of his career. Since the 1980s Clapton has performed its title track — a song for which singer Rita Coolidge claims she is owed a co-writing credit — in a revised blues acoustic guitar style, allowing Clapton to acknowledge his devotion to a band he loved but ultimately had to leave behind.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.