An Oral History of Derek and the Dominos' 'Layla'

Eric Clapton's anguished valentine to his best friend's wife reinvented his career and remains a rock and roll milestone 50 years later.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Eric Clapton never made an album as personal or as emotionally naked as the one he made anonymously: Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs.

Credited to Derek and the Dominos, and featuring an appearance by a then-unknown Duane Allman, the 1970 double-album was a valentine of aching and longing for a woman whose own identity was, at the time of its creation, known to only a few.

They included Clapton’s bandmates - keyboardist and singer Bobby Whitlock, bassist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon - his longtime friend George Harrison, and Harrison’s wife, Pattie, the object of Clapton’s affection. His Layla.

Clapton had come to know Pattie as his friendship with Harrison developed in the mid 1960s. By the end of the decade, Harrison was deep into studying and converting to Hinduism, leaving the two more time to spend together, alone.

Our names got in the way - all that supergroup hype. The best stuff we did was when we were just jamming. That’s what Blind Faith was all about

Eric Clapton

As their feelings for each other grew stronger, Clapton encouraged Pattie to leave Harrison, despite his friendship with him, and in spite of the fact that he was already deeply involved with Alice Ormsby-Gore, a socialite and daughter of the British politician Sir David Ormsby-Gore.

Pattie encouraged Clapton’s attentions, teetered on the brink, and still resisted. “I was a bachelor when I made that album, really,” Clapton said. “I had various optimisms about becoming embroiled with Pattie, but we weren’t at that moment in a relationship. It was just something I was trying to write on the wall. And so Layla was that - a proclamation. But it was as anonymous as can be.”

The name Layla - “of the night” - was more than a cover. It was a literary appropriation suited to the romantic circumstances in which Clapton chose to stake his friendship and mental health. Its source is an epic poem written in the 12th century by Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi, and based on a 7th century story that is the equal of Romeo and Juliet.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In Nizami’s telling, the young man Majnun is mad with passion for Layla, but his proclamation of love for her is considered an abomination that violates the secrecy of divine love.

Layla is given in marriage to another man, but when he dies she’s confined to her house for another two years. Layla dies in torment, and Majnun weeps at her grave before expiring. It’s torridly melodramatic stuff. And it neatly summed up Clapton’s desperation.

Beyond his feelings for Pattie, Clapton had another reason to go undercover: He was tired of fame. The 1960s had seen him rise from obscurity to prominence, first as a member of the Yardbirds and then as the hotshot guitar slinger in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

It was around that time that an unknown fan spray-painted “Clapton Is God” on a corrugated metal wall in Islington, London.

What I really loved about that album was nobody knew who we were. It was the most pure experience I’ve ever had in terms of making an album and then promoting it anonymously

Eric Clapton

In the following years, the sentiment expressed in graffiti would be embraced by guitarists and music fans across the continents when Clapton took his electric guitar playing to greater heights in Cream, the commercially successful supergroup trio he formed with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker in 1966.

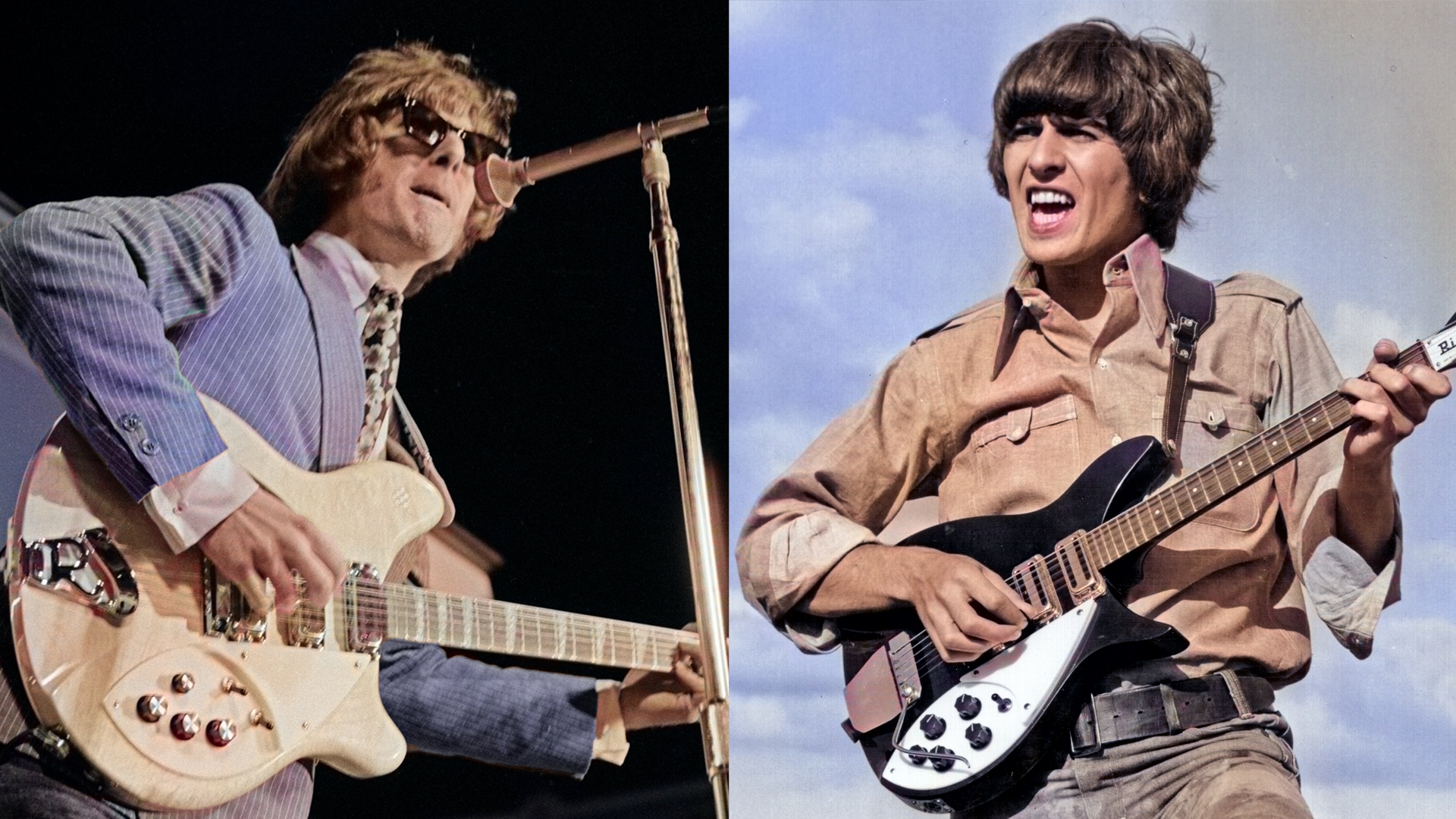

But by 1968, he’d had enough. Hoping to tone down the theatrical aspects of Cream’s blues-rock, he launched Blind Faith, a comparatively low-key affair with Baker, Steve Winwood and Rick Grech. Assembled quickly, the group recorded one album before going out on tour woefully underprepared.

Lacking even an hour’s worth of original material, they were forced to rely on playing the Cream songs Clapton had come to loathe. Audiences were delighted. It was the Eric Clapton they wanted, the one he no longer wished to be, and the band’s demise followed swiftly.

“Our names got in the way - all that supergroup hype,” Clapton told Guitar Player back in 1970. “The best stuff we did was when we were just jamming at Steve’s place, or at my house. We have tapes of that, which are just hours of instrumental, fun-type jazz things. That’s what Blind Faith was all about, but it was never exposed to the public.”

With Derek and the Dominos, however, Clapton set out to create a hard-working blues-rock band lacking the kind of star power of his earlier groups. Working with skilled, seasoned American musicians, none of whom were known to audiences on either side of the Atlantic, Clapton could slip undetected into record bins, charts and venues.

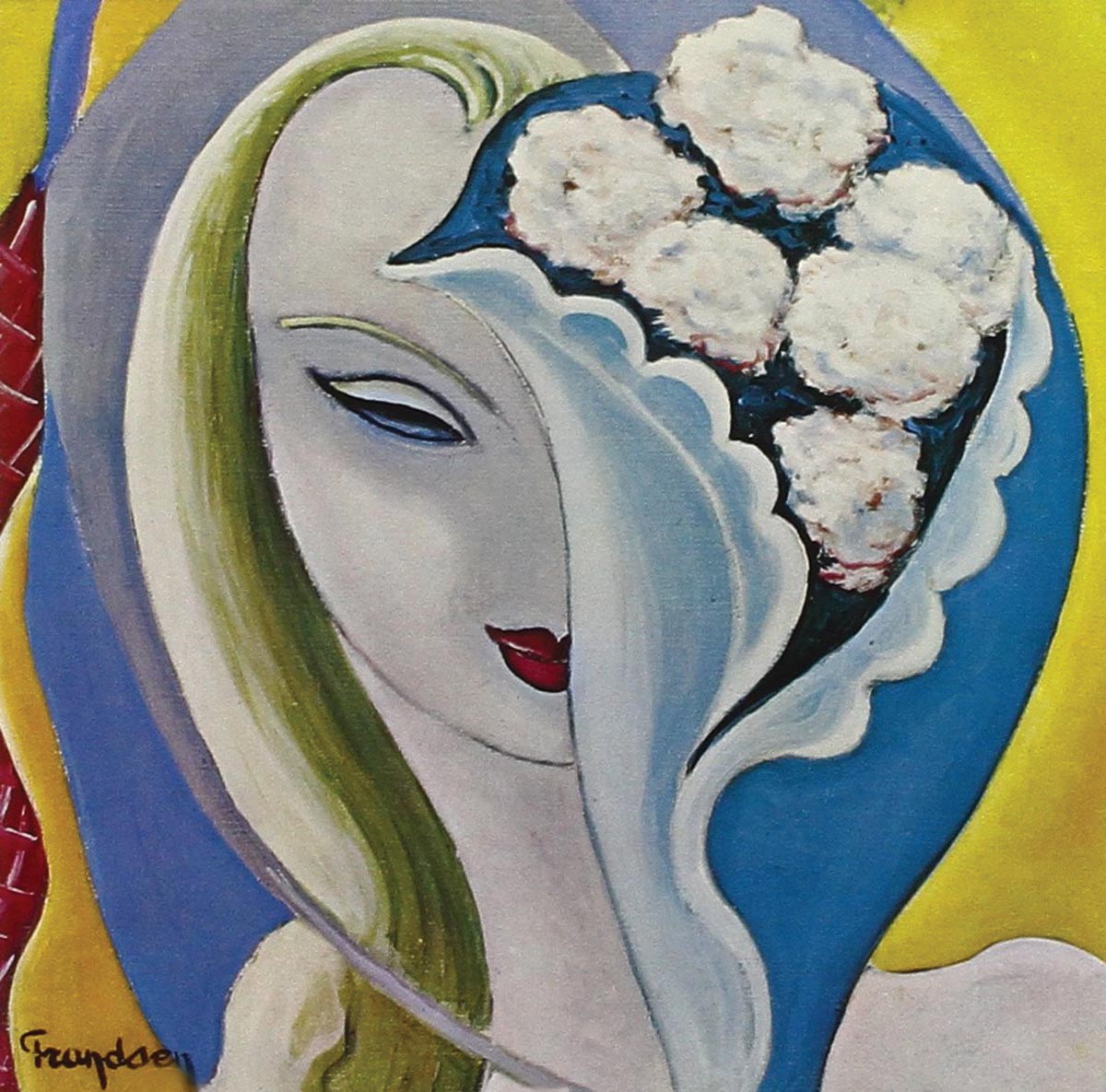

It worked. Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs was released without fanfare in November 1970. Its cover featured no band name or title, simply a rendering of the painting La Fille au Bouquet - The Young Girl with the Bouquet - by French-Danish painter Emile Frandsen de Schomberg.

We jammed a lot, sometimes it seemed like for days. We used to jam before everything when we were living at Hurtwood, and we carried that over to the sessions

Bobby Whitlock

Its back cover showed a photo of a guitar - Brownie, the 1956 Fender Stratocaster that Clapton played on the album - with a pair of black-and-white square-toed derby shoes, surrounded by a tumble of dominos.

There was nothing to indicate that the sleeve contained two slabs of anguished, potent blues rock played and sung by one of the day’s most popular and influential guitarists.

“What I really loved about that album was nobody knew who we were,” Clapton said. “We even did a tour of England, playing little clubs, and there would be nobody there, because nobody knew who we were, so they didn’t come!

“And yet there was this quartet that was one of the most powerful bands I’ve ever been anywhere near - and I was in it! The rhythm section on its own I would have watched all night. And it was a funny time, ’cause it worked by word of mouth.

“As we began touring, bit by bit people were talking about us and saying, ‘Who is this?’ ‘What is this band?’ They kind of figured it out. It was the most pure experience I’ve ever had in terms of making an album and then promoting it anonymously. It’s almost unheard of.”

But writing an album to the woman of your dreams and using it to slip undetected back into the world where you’d been a kingpin - these are acts of desperation. 50 years ago, the real salvation Derek and the Dominos offered Eric Clapton was time - a break from his past in which he could figure out what he wanted to do with his career.

“He didn’t know what his next step was going to be, but he wasn’t ready to be a solo artist and front his own group,” says Bobby Whitlock, Clapton’s co-singer, co-songwriter and keyboard-playing partner in Derek and the Dominos. “The Dominos was really just a stepping stone to his solo career, of his being able to go out there on his own and be the Eric Clapton that he became.”

The Dominos was really just a stepping stone to his solo career, of his being able to go out there on his own and be the Eric Clapton that he became

Bobby Whitlock

If Pattie Harrison served as the inspiration for Layla, it’s fair to say that her husband delivered the band. In late 1968, while in Los Angeles turning over the Beatles’ White Album master tapes to Capitol Records, George Harrison met Delaney Bramlett, a young guitarist who performed with his wife, a singer named Bonnie.

Delaney & Bonnie’s music was a mix of southern rock and soul, delivered with the raucous enthusiasm of a gospel revival. Harrison and Bramlett hit it off, and when Delaney & Bonnie issued their second album, Accept No Substitute, in 1969, they sent him a copy.

Harrison liked the record and shared it with Clapton, who heard in its muscular southern-rock hybrid an inkling of the authentic American music he wanted to make. When Blind Faith went on tour in the U.S. and Canada that summer, Clapton invited the group to open for them, joining the bill with Taste, the Irish blues-rock band fronted by guitarist Rory Gallagher.

By then, Delaney & Bonnie’s troupe had expanded to include several more musicians, including Whitlock, former Traffic guitarist Dave Mason, bassist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon, then one of the most popular session drummers of the period, with credits that included the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Mason Williams’ “Classical Gas,” several albums by the Monkees and the just-released Crosby, Stills & Nash album.

Delaney & Bonnie and Friends proved an even more potent act onstage than on record. “For me, going on after Delaney & Bonnie was really, really tough, because I thought they were miles better than us,” Clapton recalled. Eventually, he began sitting in with them and tapping a tambourine before finally playing along on guitar.

By the time the tour ended in Honolulu on August 24, 1969, Blind Faith were done as a group, and Clapton was entrenched in Delaney & Bonnie and Friends. Delaney, charismatic and brotherly, had already influenced Harrison by revealing his slide technique, which Harrison perfected into his own signature style.

Now he worked his magic on Clapton, writing songs with him, turning him on to the country-rock stylings of guitarist and songwriter J.J. Cale, and even influencing his new shaggy, bearded appearance.

We just clicked. It was like Lennon and McCartney, or Jagger and Richards. We were a quintessential writing team

Bobby Whitlock

When Clapton began recording his self-titled debut solo record that fall, it was a given that Delaney & Bonnie and Friends would serve as his backup band. Reviews for Eric Clapton were positive, and there was something on it to please both old and new fans.

“Blues Power,” composed by Clapton and pianist Leon Russell, one of the group’s Friends, was a rock number in Russell’s southern funk-soul style on which Clapton cut loose with the kind of fiery soloing that guitar fans longed to hear him play.

The acoustic “Easy Now” nodded to the gentle folk emerging from California’s Laurel Canyon, while the jangly “Let It Rain” evoked the psychedelic rock of the Byrds filtered through Delaney & Bonnie’s rousing southern gospel-revival style.

Most noteworthy, Clapton’s uptempo cover of Cale’s “After Midnight” became a hit when it was released as a single in October 1970 and would serve as the guitarist’s signature tune over the next two decades. But when recording of Eric Clapton wrapped in March, its creator had no plans to tour behind it.

He was lying low, plotting his next move and trying to convince Pattie to become his lover. He had also begun taking cocaine to salve his longing. Like his pal George, Clapton had moved from London to the countryside to escape the rock and roll lifestyle. He’d settled in Ewhurst, in Surrey, where he lived alone in a large 1910 Italianate villa called Hurtwood Edge.

It was an appropriately named hideaway for a man nursing an unrequited jones for his best friend’s wife and a growing flirtation with potentially lethal narcotics. That’s where Bobby Whitlock found him. Just 22 at the time, Whitlock was, like Clapton, uncertain of his next move.

Born in Memphis, he’d been raised in poverty, and picked cotton to survive. But Whitlock was a talented singer, organist and guitarist, and by his teens he’d established himself as a local musician with a powerful voice and easygoing manner.

Through his performances he’d befriended many of the acts signed to the local Stax label, including Albert King, Sam & Dave and the label’s house band, Booker T. and the MGs.

He’d also become the first solo white artist signed to the label. It was there that he met Delaney & Bonnie when they recorded their 1968 debut, Home, as Stax artists. He joined up as one of their Friends for the 1969 followup, The Original Delaney & Bonnie, popularly known by its subtitle, Accept No Substitute.

The work was enjoyable, and touring with them allowed Whitlock to meet performers like Harrison and Clapton. But following their work on Eric Clapton, the couple considered themselves stars. As the group’s dynamics changed, the members peeled away. Whitlock was among the last to leave.

He departed in early 1970 during the making of To Bonnie from Delaney, an album helmed by future Layla producer Tom Dowd and featuring an appearance by Duane Allman, who would soon be making his way into Whitlock’s world.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do after I left Delaney & Bonnie,” Whitlock says. “I just knew I didn’t want to go back to Memphis, and I didn’t want to stay in L.A.” Despondent, he called an old friend from Stax, guitarist Steve Cropper, and asked for his advice.

Bonnie and Delaney had Eric completely cornered. No one could get near him when they were around

Bobby Whitlock

“Steve said, ‘Call Eric and just see what he’s up to,’” Whitlock recalls. “He said, ‘Just ask him if you can visit for a couple days.’ I said I didn’t have any money, and he said, ‘Don’t worry about that. Just call him.’

“So I called, and Eric picked up the phone! And I told him, ‘Hey, I just left Delaney and Bonnie, ’cause they’re driving me nuts, and I have to get out of here.’ And he said, ‘Why don’t you come on over?’ And that was a Wednesday. And I called Cropper back, and he said, ‘I’ll have a ticket for you tomorrow.’

“And so the next day, a one-way ticket to London showed up with my name on it. I got on the plane and took off with three hundred dollars, my guitar and a suitcase, and the clothes on my back. I arrived at Heathrow and exchanged my dollars for pounds. I got a cab and said, ‘Take me to Hurtwood Edge!’”

It was a presumptuous move on Whitlock’s part. Clapton had been impressed by Whitlock’s keyboard talents and even allowed him to stretch out his gutsy vocal chops singing a soulful response vocal on “Let It Rain.” But the two men weren’t close.

“It was a cordial friendship,” Whitlock explains, “’cause Bonnie and Delaney had him completely cornered. No one could get near Eric when they were around. Our friendship didn’t really begin until I went to England to visit him.”

Over the next weeks, Clapton took the young American around London and introduced him to his friends, including former Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky, and showed him some of London’s hot music spots. Mostly though, they hung around Hurtwood Edge, playing guitar and writing songs together in the manor’s TV room.

“‘I Looked Away’ was the very first one,” Whitlock says. “And then ‘Anyday,’ and then ‘Tell the Truth.’ It felt really natural for us to write together, because we were friends first and we weren’t writing to make money or anything like that. We were just writing songs to have something we could play together.”

Guitars were everywhere at Hurtwood Edge, and Clapton constantly tinkered with them, exchanging hardware and making sure the action was precisely an eighth of an inch high.

Years before, he had fallen for the Gibson Les Paul model when he saw Freddie King playing one on the cover of Freddie King Sings the Blues.

I remember hearing ‘Hey Jude’ by Wilson Pickett and calling either Ahmet Ertegun or Tom Dowd, and saying, ‘Who’s that guitar player?’ To this day, I’ve never heard better rock guitar playing on an R&B record

Eric Clapton

“I went out after seeing that cover and scoured the guitar shops and found one,” Clapton said. “That was my guitar from then on, and it sounded like Freddie King.” But in 1967, while in Cream, Clapton bought his first Fender Stratocaster, a model played by his idols Buddy Guy and Otis Rush. He’d first put the Strat, dubbed Brownie, to use on Eric Clapton.

Now, more and more, it was the only electric guitar he played. Clapton and Whitlock worked on songs daily and were surprised to find they were such natural and prolific collaborators. “We just clicked,” Whitlock says. “It was like Lennon and McCartney, or Jagger and Richards. We were a quintessential writing team. The collaboration was just perfect, and the songs poured out effortlessly.”

For Whitlock, life at Hurtwood Edge was idyllic. Clapton was a gracious host and was now becoming both a musical partner and friend. But the young American had arrived in England with little money in his pockets. After just a few weeks, he was nearly penniless.

“Eric and I were out having lunch one day, and I said to him, ‘Let me get it!’” Whitlock recalls. “And I went to pay - and I didn’t have any money for that dad-gum meal. And I said to him, ‘I’m going to have to go back home. I’m running out of money.’

“And he said, ‘Me too. As a matter of fact, I thought we were gonna put a band together. Let’s go to the office tomorrow and get both of us fixed up with a weekly draw.’” The next day, they visited Clapton’s manager, Robert Stigwood.

The guitarist introduced Whitlock as his new bandmate, and Stigwood set them up with a weekly allowance of £150, about $2,300 in 2020. Says Whitlock, “I’d never had that much money in my life.” Steve Cropper’s advice had paid off. Whitlock suddenly had money, a music partner and the beginnings of a band. And, almost immediately, he was offered the gig of a lifetime.

They did whatever seemed best at the moment for a given part. It just happened, and if you didn’t catch it, you blew it. The spontaneity of that whole session was absolutely frightening

Tom Dowd

“Shortly after our meeting with Robert Stigwood, Eric and I were having lunch at Hurtwood, and the phone rang,” Whitlock recalls. “Eric picked it up, and he was going, ‘Mm-hmm. Yeah. Okay. Let me ask Bobby and see what he thinks.’

“He hung up and he says to me, ‘That was George.’ And I said, ‘Harrison.’ He says, ‘Yeah. He wants us to put together a group and be the core band for his new record. Why don’t you give Jim and Carl a call and tell them what’s up?’

“So I called Jim Keltner - I thought that was the Jim he meant,” Whitlock continues. Keltner had preceded Jim Gordon as Delaney & Bonnie’s drummer. “But he was busy with [Hungarian guitarist] Gabor Szabo and wouldn’t be free for a month. So I called Carl Radle, and he was finishing up a jazz album, but he said he’d be out shortly. And all of the sudden, Jim Gordon shows up!”

Radle and Gordon had just finished their stint as part of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour and returned to Delaney and Bonnie, only to learn they’d been fired. After receiving Whitlock’s invitation to come to England, Radle called Gordon. The drummer was so eager that he arrived ahead of the bassist.

Heroin was something I had to go through. We all went through it. And there was a lot of it

Bobby Whitlock

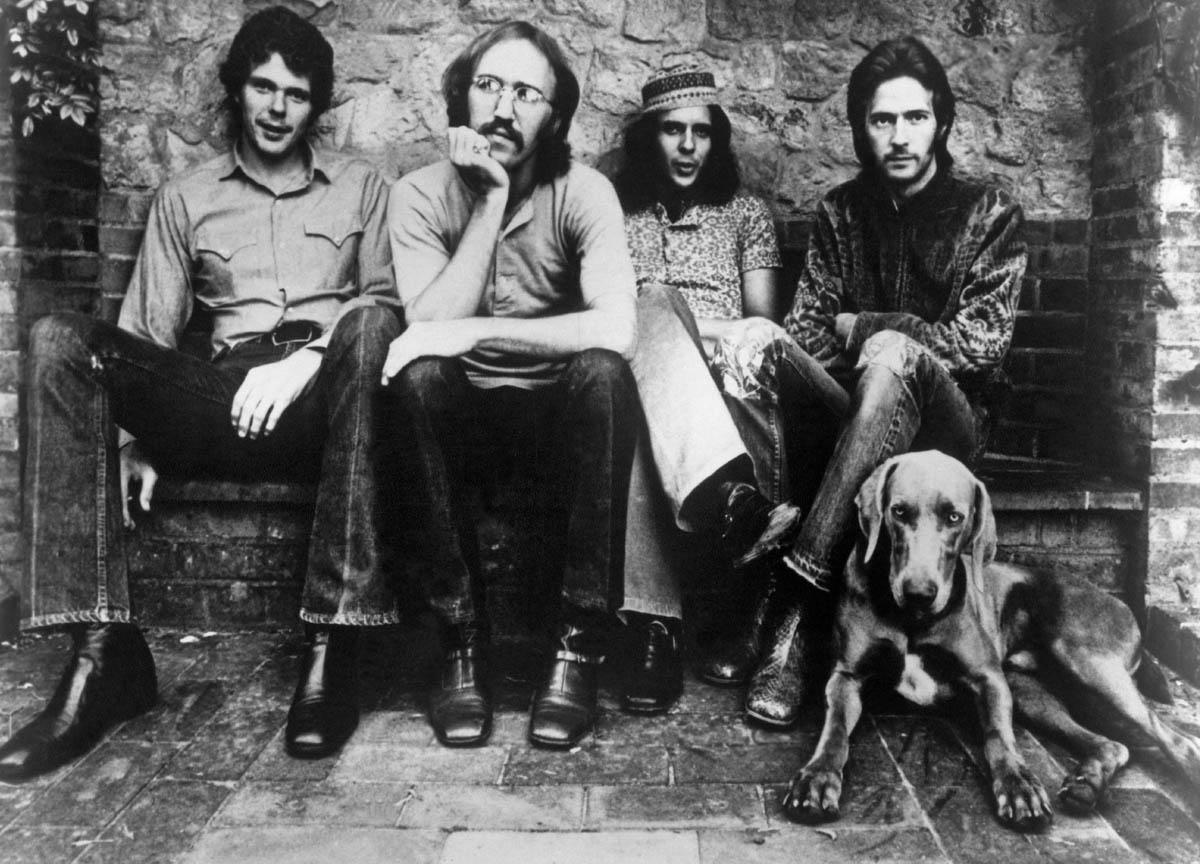

“We’d really wanted Jim Keltner, and now Jim Gordon was here,” Whitlock says. “So we had a little powwow, Eric and me. And I said, ‘Keltner isn’t going to be here for a month, and Gordon is here now. Why don’t we just ask him to do it?’ Eventually Carl showed up, and we all were living there at Hurtwood. And that’s how Derek and the Dominos came together.”

Over the next month, Clapton, Whitlock, Radle and Gordon lived communally at Hurtwood Edge while working on Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. Though it’s unknown exactly who played on which of the album’s songs, Whitlock says he, Clapton and Gordon were among the performers on its breakout hit, “My Sweet Lord.”

Radle likely arrived in England after the track was recorded and appears elsewhere on the album. When they weren’t working on Harrison’s sessions, they rehearsed their own songs.

Singing about his unrequited love for Pattie while logging hours on her husband’s debut solo album was too much for Clapton. He’d threatened her that, if she didn’t leave George, he’d start taking heroin, and he began to make good on the promise. Being a wealthy musician, Clapton could afford the best. The purity of product was such that he didn’t need to inject it; he could get high just by snorting it.

Eventually, all the Dominos got onboard the smack wagon. “It was something I had to go through,” Whitlock told author Jan Reid. “We all went through it. And there was a lot of it.” The recording of All Things Must Pass lasted through October, but the basic tracks involving Clapton, Whitlock, Radle and Gordon were wrapped up in June.

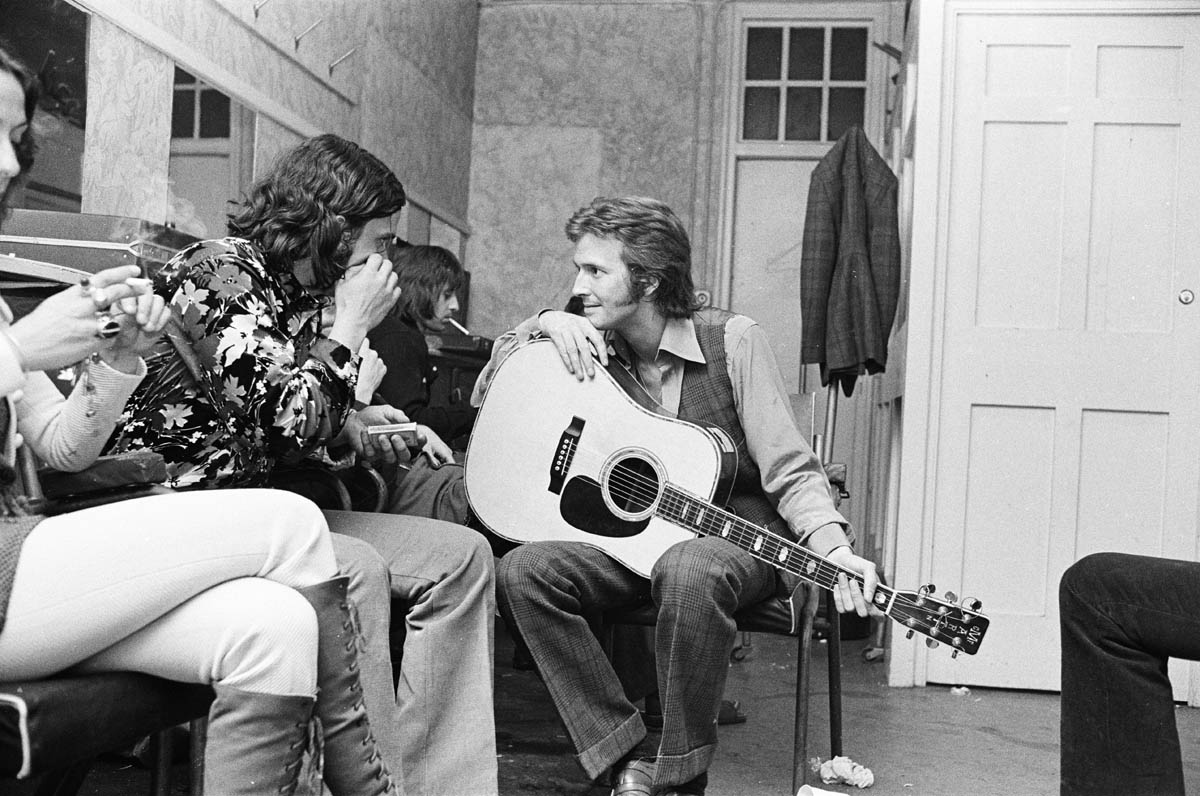

With guitarist Dave Mason in tow, Clapton and his musical partners decided it was time to bring their new music to an audience. On June 14, the group performed at a charity concert at London’s Lyceum Ballroom. Among those appearing were Harrison and English pianist Tony Ashton, who had a past association with the Beatles and, in particular, Harrison.

Ashton had taken to calling Clapton by the nickname Del in homage to Delaney’s influence on his music and shaggy appearance. Clapton recalled that, when the subject of the band’s name came up backstage, Ashton suggested Del and the Dominos. Whitlock says the name was actually the Dynamics, while Jeff Dexter, who announced the band at the show, claims Derek and the Dominos had been selected.

Whatever the real story, the audience at the Lyceum was underwhelmed by the performance. They wanted to see Clapton as a guitar slinger, not as a singing frontman for a band of unknown musicians.

Regardless, on August 1, Derek and the Dominos launched a three-week tour of small clubs in England. Clapton’s name was never mentioned in the publicity, and the entry fee was never more than £1.

I think there were five guitars on 'Keep on Growing' - everybody was like racehorses at the starting gate, just waiting to shove those faders up to see what this sounded like

Bobby Whitlock

Clapton says the group performed to “no more than 50 or 60 people” at any show. “And I loved it.” If nothing else, the small tour convinced Clapton that he had to get the band into the studio while it was hot.

He had Stigwood ring up Tom Dowd, the producer who had worked on To Bonnie from Delaney. A venerated recording engineer for Atlantic Records who had shaped the sound for countless artists on that label and its subsidiaries, Dowd had engineered Cream’s Disraeli Gears and the studio-recorded half of Wheels of Fire.

Clapton’s choice of Dowd was serendipitous. At that moment, the audio guru was at Atlantic’s Criteria Studios, in Miami, producing the second album from a rising young rock group from Jacksonville, Florida, called the Allman Brothers Band.

Dowd already knew their guitarist Duane Allman from his session work for Atlantic artists like Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett. The sessions for Derek and the Dominos’ album would slot in nicely for late August. The date was set. On August 26, hot off their three-week tour, Clapton, Whitlock, Radle and Gordon arrived in Miami to begin recording Layla, at Criteria.

Whitlock recalls the sessions as fast moving and productive. The songs were tracked live in the studio in a matter of one or two takes, and in essentially the same order that they appear on the album. Overdubs consisted mostly of additional vocals, guitar parts and percussion, and were created immediately after the main recording was made.

Eric had the ability to get great tone with just his Fender Strat and a tiny little tweed Champ or a battery-powered Pignose. It was just about making it simple

Bobby Whitlock

But between the songs, the group jammed for hours, “We jammed a lot, sometimes it seemed like for days,” Whitlock says. “We used to jam before everything when we were living at Hurtwood, and we carried that over to the sessions.”

From the start, the sessions proved fruitful. The band quickly dispatched with “I Looked Away,” the first song Clapton and Whitlock wrote together. The two recorded their Sam & Dave-style vocals live, occasionally singing slightly off mic, a tendency that carried through the album’s sessions and enhanced its sometimes rough, live-in-the-studio feel.

Next up was “Bell Bottom Blues,” another Clapton–Whitlock tune, though, due to a clerical error, only Clapton was credited as its writer on early album pressings. The song’s lyrics were inspired by Pattie, who had requested Eric bring her a pair of hip-hugging Landlubbers bell-bottom blue jeans from America.

The band’s penchant for jamming showed itself early on and resulted in one of the album’s funkiest songs, “Keep on Growing.”

“After recording ‘I Looked Away’ and ‘Bell Bottom Blues,’ we were jamming on this thing with a kind of Latin beat, and it was just really great,” Whitlock says. “And when we were finished, Eric said, ‘I want to put another guitar on this,’ and he put on a second part without even listening to the first part he’d recorded.

“All he was listening to the whole time was bass, drums and organ. And when he was done with that, he did it again. And I’ll be damned if he didn’t do it again! And all he was doing was putting in sporadic notes here and there. And I was thinking, 'He’s got something going on.'

I got halfway through the first verse, and I said, ‘Stop!’ I said, ‘Come out here and sing this with me, Eric. Let’s do our Sam & Dave thing

Bobby Whitlock

“And sure enough, when he was done - I think there were five guitars on there in the end - everybody was like racehorses at the starting gate, just waiting to shove those faders up to see what this sounded like. And when they did - whoa, boy! It all fit together like cogs in a wheel. It was amazing.

“And Tom Dowd said, ‘Well, let’s just can this one’ - you know, put it up on the shelf. And I said, ‘No, man, give me 20 minutes to write some lyrics.’ So I went out to the foyer of Criteria and sat down with a manila envelope and a pen, and the words just poured out like water.”

Inspired by Whitlock’s early life in Memphis, “Keep on Growing” is about feeling those first hopeful, romantic longings, a sentiment that fit perfectly into Layla’s theme of idealized love and its eventual dissolution.

“It was like I was expressing my relatively short, inexperienced life,” he explains. “And when I was through writing, I went back into the studio. Eric and Tom were in the control room, and I said, ‘Hit “record.”’ I got halfway through the first verse, and I said, ‘Stop!’ I said, ‘Come out here and sing this with me, Eric. Let’s do our Sam & Dave thing.’ And he did, and it just happened like that. It’s exactly what you hear on the recording.”

The recording even captured a vocal miscue, saving it for posterity. Amid one of Clapton’s lengthy solos, he and Whitlock launch into another verse, singing “Baby” before realizing the solo hasn’t finished yet. “We just left that in,” Whitlock says. “That’ll give you a clue to how raw that thing was. We made an error in judgment. But it worked.”

Duane Allman was excited when Dowd told him he was producing the debut album from Clapton’s new band.

“Duane said he’d love to meet him, and I said I could arrange that,” Dowd told John Tobler and Stuart Grundy, authors of 1982’s The Record Producers. “But he said he’d rather sneak in some day when we were recording.” Allman didn’t know it, but Clapton was already familiar with his work on Wilson Pickett’s 1969 cover of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.”

“I remember hearing ‘Hey Jude’ by Wilson Pickett and calling either [Atlantic president] Ahmet Ertegun or Tom Dowd, and saying, ‘Who’s that guitar player?’” Clapton said. “To this day, I’ve never heard better rock guitar playing on an R&B record.”

As it happened the Allman Brothers Band was playing a benefit concert at the Miami Beach Convention Center on the night of August 26, the first day of the Dominos’ sessions. “Tom said, ‘Hey, man, the Allman Brothers are in town,’” Whitlock recalls. “‘Do you wanna go see them?’”

In an oft-told story, the four members of Derek & the Dominos were snuck into the show and placed between the security barrier and stage as the band were performing. “It was an open-air concert, and the roadie sat us down on the grass about six feet from the apron of the stage,” Dowd recalled.

Allman, who was in the midst of an extended solo and had his eyes closed, didn’t see the group come in. “Eric was looking up, and Duane opened his eyes and stopped playing,” Dowd continued. “His mouth dropped open to about his chest, and he went, ‘Aaah…’” Allman quickly recovered but turned his back to the audience, fearful of making eye contact with Clapton.

When Duane arrived, that’s where ‘Key to the Highway’ and the other covers came in. The whole thing changed

Bobby Whitlock

“When the concert was over, he said, ‘Why did you bring him here? I’m not playing well tonight,’” Dowd continued. “And in the meantime, Eric is saying, ‘I want to meet him. How does he do that?’ It was love at first sight.”

Afterward, the two bands convened at Criteria for a night of jamming. When it was over, most of the Allmans left, but Duane stuck around.

“Eric and Duane just clicked in a special way,” Whitlock says. “They could both relate through their love for Elmore James and Robert Johnson, and all those great blues guitarists. When Duane arrived, that’s where ‘Key to the Highway’ and the other covers came in. The whole thing changed when he came onboard.”

Allman’s very first session with the group provided Layla with one of its most inspired jams, “Key to the Highway.” At the same time that the Dominos were recording at Criteria, one of its studios was being used to record a new album by 1960s pop singer Sam the Sham.

Born Domingo Samudio, the Memphis musician was an old family friend of Whitlock’s who had made his name on novelty songs like “Wooly Bully” and “Li’l Red Riding Hood.” With his career having pretty much run its course, Sam was hoping to kickstart it again with a new album under his real name.

The Dominos heard him playing the blues standard “Key to the Highway” and quickly began jamming it themselves, as it was one tune that both the group and Allman knew. Though Dowd had decreed that the tape machines had to be running at all times during the sessions, he’d briefly departed the control room before the group began playing and had left the mixing console’s faders down.

Hearing the music begin, he ran back to the control room, yelling, “Push up the faders!” The remainder of the song was captured, but the recording’s unusual fade-in is due to Dowd’s uncharacteristically poor timing.

“They did whatever seemed best at the moment for a given part,” Dowd later recalled. “It was never gonna happen again. It just happened, and if you didn’t catch it, you blew it. The spontaneity of that whole session was absolutely frightening.”

One thing the sessions weren’t was very loud. To Dowd’s surprise, Clapton had done away with the Marshall stacks from his time with Cream. He walked into Criteria carrying just a pair of small Fender combos, although exactly which models remains something of a mystery, even to those who were present.

It was a purist sound. There was no slapback echo, no fuzz tones

Bobby Whitlock

In one telling, Dowd recalls Clapton showing up with “a Champ under one arm and a Princeton under the other, and that was it. He and Duane used those amps, switching back and forth.”

To the contrary, in an interview with Vintage Guitar magazine, Joe Bonamassa said Dowd told him Clapton used a blackface Vibro-Champ into a blackface Princeton Reverb with the volume and treble on full and the bass dialed down to zero.

Whitlock muddies the waters further by claiming Clapton alternated between a five-watt tweed Champ and a prototype Pignose battery-operated amp. “It was one of the very first ones ever made,” he says of the Pignose. “This guy brought two of them by and gave them to Eric, and Eric gave the other one to Duane when he finally showed up.”

Though the Pignose wouldn’t officially debut until the 1973 NAMM show, its creators reportedly had been offering preproduction models to guitarists since 1969. For Clapton, getting back to basics meant relying on an irreducible rig - his Fender Strat straight into the most Spartan of amps.

There are conflicting stories over which amps Eric Clapton and Duane Allman used in the studio, but producer Tom Dowd remembers a Fender Champ in the mix.

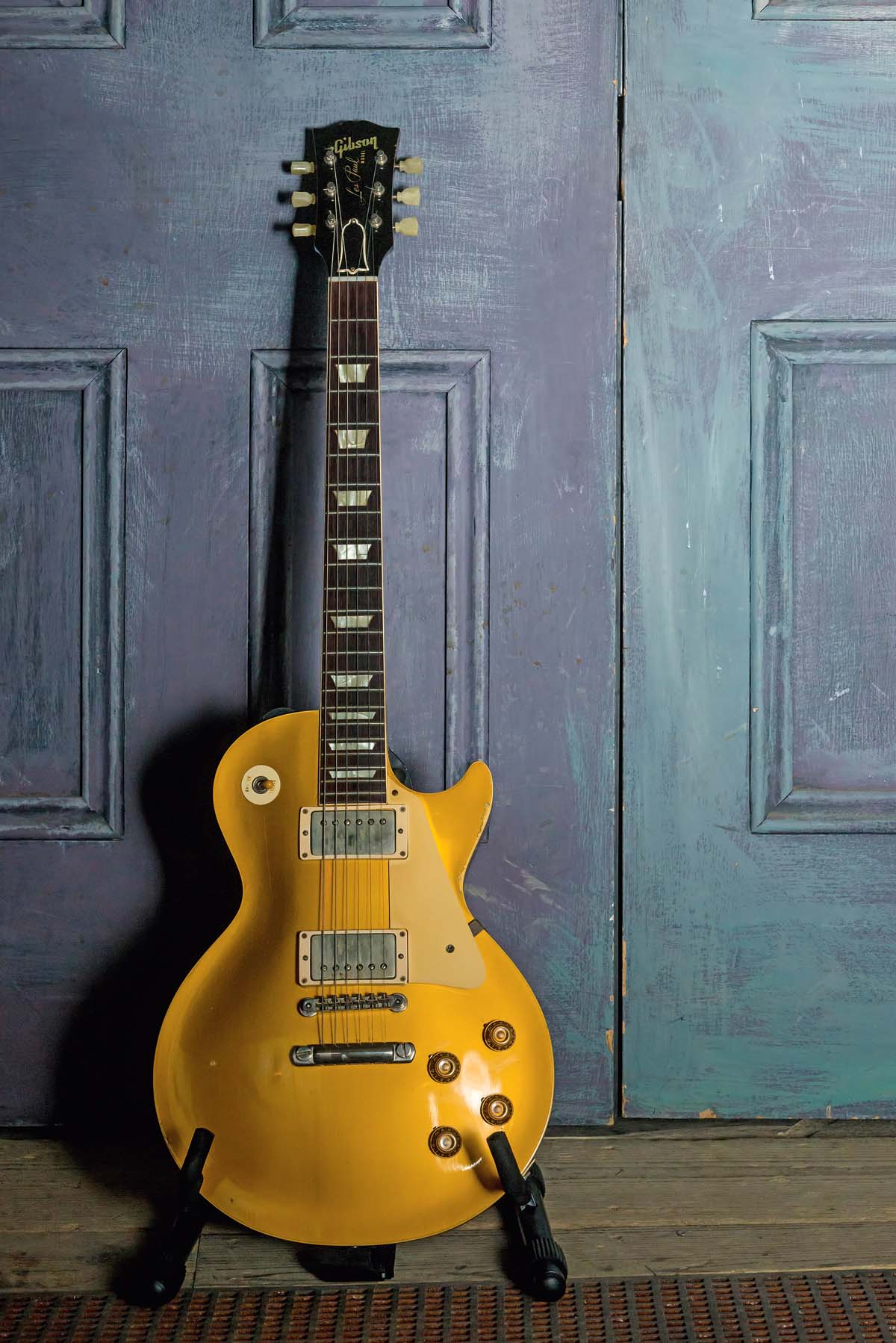

Duane Allman tracked his parts on a '57 Goldtop, serial number 7 3312.

“It was a purist sound,” Whitlock explains. “There was no slapback echo, no fuzz tones. It was keeping it real simple and getting back to being pure. Eric had the ability to get great tone with just his Fender Strat and a tiny little tweed Champ or a battery-powered Pignose. It was just about making it simple.”

In addition, Layla engineers Ron and Howard Albert recall that two Champ amps were used during the recording of the piano coda to “Layla,” and both were placed on top of the studio piano.

“If you looked through the control-room glass, the piano was to the left,” Howard Albert told Sound on Sound magazine, “and on top of the piano, which had the lid closed, were our [Fender tweed] Champ amps that Eric and Duane both used.”

The Alberts also recall that Clapton used a Fender Vibratone rotary speaker on “Layla,” which can be clearly heard near the top of the piano coda in a riff Clapton plays just before the full band kicks in.

Clapton had been a fan of Leslie rotary speakers since first hearing Robbie Robertson use a homemade rotary speaker created by Garth Hudson, the Band’s keyboard player, on that group’s debut album.

“Eric was enamored with [the Vibratone], and we used it a lot,” Ron Albert says. “We had a great big Variac speed control on it,” Howard adds, “so we could actually change how fast it went.”

As for guitars, it’s well established that Clapton relied on Brownie, the 1956 Strat he’d purchased in 1967 during his tenure with Cream. Allman, for his part, used his gold-top 1957 Gibson Les Paul.

“The sound of those two guitars together was perfect and complementary,” Whitlock says. “You just couldn’t have asked for anything better that that.” As it happened, Clapton and Allman’s friendship was as symbiotic as their guitar playing. Whitlock witnessed many moments of camaraderie between them and recalls the profound impact it had on his own awareness of what they were accomplishing in the studio.

“One night after we had finished up recording for the day, we went on back to Eric’s room,” he remembers. “We were all drinking whisky and playing guitars, and I was listening to Eric and Duane talking about Robert Johnson, Elmore James and so on, and playing Bill Broonzy stuff. ‘Cause Eric’s like a volume of history when it comes to the blues. He knows all about it, and who did it, and who played what lick where.

“But I was standing there, leaning up against the wall and taking all this in, knowing that this is some really important stuff that’s going down, and I’m a witness to it. And these two young guys - we were all in our 20s --they were like two old, sage black blues guys talking it over with a bottle of whisky, and then playing the music, right there. Man, it was so cool!

“And it was then that I took the photo of Eric and Duane together that’s in the album gatefold. It was the one time I felt truly privileged to be there, at the right time, the right place, and in the right frame of mind.”

With Duane Allman onboard, the sessions continued to move at a quick pace, with the band performing both originals and covers as well as playing extended jam sessions.

Among the originals was “I Am Yours,” a Clapton composition that includes lyrics taken directly from Nizami’s poem about Layla and Majnun, and “Anyday,” a Clapton-Whitlock tune with an optimistic message, on which Clapton handles slide work. (“Perfectly in tune, too, I might add,” Whitlock notes).

Clapton and Whitlock do their Sam & Dave thing again on the uptempo “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” another joint composition and one that encapsulates Clapton’s frustrations over his relationship with Pattie Harrison - indeed, the song’s name could serve as a subtitle for the album.

The group also tackled “Tell the Truth,” a Clapton-Whitlock song first recorded at a faster tempo during the All Things Must Pass sessions in England, with Phil Spector producing.

In addition to “Key to the Highway,” the band covered “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” a blues standard written in 1923 by Jimmy Cox and popularized by Bessie Smith. Recorded by the Dominos at the suggestion of Sam the Sham, the song was one of the first blues standards Clapton learned to play in the acoustic fingerpicking style of Big Bill Broonzy.

The guitarist also led the band through a performance of “Have You Ever Loved a Woman,” a Billy Myles blues standard recorded by Freddie King in 1960. Clapton had previously recorded a live version with John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers.

Also included among the selections was the Chuck Willis country blues tune “It’s Too Late,” recorded, by Whitlock’s account, as an audition for The Johnny Cash Show, the country legend’s music-variety TV show, on which the Dominos performed on November 5, 1970.

Jimi Hendrix had sat in with us a couple of times when we were out playing. Eric wanted to do ‘Little Wing’ as a tribute, because he really revered him

Bobby Whitlock

But of all the covers on Layla, there is little to compare with the group’s version of Jimi Hendrix’s “Little Wing.”

Originally recorded by Hendrix as a sensuous slow blues for his album Axis: Bold As Love, the song becomes a torrid lament in the hands of Clapton and the group. Both Clapton and Whitlock wail the lyrics in tandem, while the band attacks the arrangement with one of the heaviest performances on the album.

“Jimi Hendrix had sat in with us a couple of times when we were out playing,” Whitlock recalls, “so I knew him and had met him. Eric wanted to do ‘Little Wing’ as a tribute, because he really revered Jimi Hendrix.”

Unlike Hendrix’s original, the Dominos’ version features a powerful three-chord riff, created by Allman, that opens the tune and appears between its verses.

Whitlock says he was unfamiliar with the song when they cut it. “I was writing out the chord sheet and lyrics for myself when Eric and Duane were working out their parts,” he explains. “We played the song part way through to get the balance [levels], and then it was ‘roll tape.’ And it was first take. Done.”

Allman’s “Little Wing” chord riff provides the tune with a central memorable motif missing from Hendrix’s recording, turning the gentle ballad into a mammoth blues-rocker that is among Layla’s most powerful cuts. Remarkably, Allman worked his magic a second time on the sessions with Layla’s title track when he devised the seven-note opening lick that is the song’s calling card.

“Duane suggested it, and he came up with it,” Whitlock confirms. “We already had the song together, but it just started out completely different when we worked it up in England. And Duane said, ‘How about starting it this way?’”

Perhaps playing off the desperation in Clapton’s lyrics, Allman cleverly lifted the first half of the opening melody from Albert King’s “As the Years Go Passing By,” where the bluesman sings, “There is nothing I can do if you leave me here to cry.” Whitlock recalls that, originally, Allman played the line slower than it’s heard on the recording.

“It was Eric’s idea to play it fast,” he says. “Duane played it, but Eric sped it up.” At this point, “Layla” consisted of only the first three minutes and 10 seconds heard on the recording. With that track finished, the album sessions were completed on September 10.

Duane is out of tune, that’s all there is to it. But you know, it’s almost become endearing after all this time

Bobby Whitlock

“Afterward, we were in the foyer just having a drink,” Whitlock recalls. “And Eric said, ‘We’ve got room for one more on this’ - because it was going to be a double album. ‘Why don’t you do “Thorn Tree”?’ So we went back in and did ‘Thorn Tree.’” “Thorn Tree in the Garden” is a Whitlock composition that predates Layla by a year or two.

Whitlock wrote it while living communally with the Delaney & Bonnie group. The keyboardist had brought a cat and dog into the house, but the others felt the space was already too crowded. Whitlock found a home for the cat, but upon returning to the commune found his dog had been given away. Distraught, he sat in his room and put his grief into a song about losing a lover.

With its gentle acoustic guitar work and late-hours mood, “Thorn Tree in the Garden” made a fitting after-party coda to the album’s raucous electric guitar blues-rock and, particularly, Clapton’s own strained and appropriately histrionic vocal performance on “Layla.”

Everybody wanted Eric to play with abandon, like he had with Cream. What we were doing was so far from that, because he was a blues purist, and his roots are in the blues

Bobby Whitlock

The band was back in England when Whitlock says they were told to return to Criteria for one final recording. Musically and emotionally, “Layla” was perfect. But Clapton decided that, as the album’s title song and penultimate track, it needed something more.

That something was a piano composition written by drummer Jim Gordon and his former girlfriend, Rita Coolidge, who had been a popular singer with Delaney & Bonnie as well as with Joe Cocker.

“Jim and Rita had written this song called ‘Time,’ back in the Delaney & Bonnie days,” Whitlock explains. “They wanted me to play piano on it, with Rita singing. But I told them, ‘I don’t feel this at all.’ And it turns out that Jim brought it to Eric after we’d already recorded the album, and Eric wanted to add it to the end of what we’d recorded for ‘Layla.’ And I was totally against it. It didn’t seem like it was part of anything that we were doing.”

For years, guitarists have noticed that “Layla” is pitched slightly sharp. No one seems to know why, but it’s possible the recording was sped up to bring it in tune with the piano coda when the two were joined together. What’s particularly evident is that Allman’s slide guitar, which is in tune for the first half of the song, is decidedly flat for the piano coda.

As Whitlock confirms, his slide part was overdubbed on the coda, most likely with his guitar tuned to pitch rather than to the modified pitch of the recording. “Duane is out of tune, that’s all there is to it,” Whitlock states flatly. “But you know, it’s almost become endearing after all this time. People actually try to play out of tune when they do the song now.”

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs was issued on November 9, 1970, less than three months after the release of Clapton’s own solo debut, Eric Clapton. Though it may seem surprising today, Layla received mixed reviews, with some critics commending Clapton’s vocals and others declaring them “weak” and even “atrocious,” while giving high marks to songs with fiery guitar work and low scores to the love songs.

“Everybody wanted Eric to play with abandon, like he had with Cream,” Whitlock says. “Everybody wanted that flurry of guitar activity. What we were doing was so far from that. He wanted to get away from that himself because he was a blues purist, and his roots are in the blues.”

Although Layla initially failed to get much airplay in the U.S., the album sold fairly well, reaching Number 16 on the Billboard Top LPs chart. In Clapton’s native country, it failed to chart at all, in large part because Polydor refused to put promotion behind it. In desperation, Stigwood had stickers declaring “Derek Is Eric” printed up and placed on the records, but to no avail.

Remarkably, Layla began to take off in the years after its initial release. The album re-entered the U.S. charts in 1972, 1974 and 1977. By the end of the decade, many critics had begun to reassess it favorably. Around the time of Clapton’s career revival in the 1990s, following his MTV Unplugged performance, Layla began to be embraced as one of his finest albums, and a rock and roll milestone.

As for Derek and the Dominos, the group fizzled out not long after the album was released. Following a tour in the U.K. and U.S. from September 20 through December 6, the group attempted a second album but broke up before it could be completed.

Tragedy was partly to blame. Clapton was crushed by the death of Jimi Hendrix on September 18, 1970, just two days before Derek and the Dominos commenced their U.K. tour.

Then, on October 29, 1971, Duane Allman died of internal injuries after crashing his Harley-Davidson Sportster motorcycle in Macon, Georgia. He was just 24. Clapton, who considered Allman “my musical brother,” was devastated. But he was also demoralized by the response to Layla.

Most crushing was the reaction of Pattie Harrison, who finally told him their relationship was over. The rejection pushed Clapton deeper into drug addiction and depression, resulting in a three-year career break punctuated only by his participation in George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh, on August 1, 1971.

Being Derek was a cover for the fact that I was trying to steal someone else’s wife. That was one of the reasons for doing it

Eric Clapton

Speaking of the Dominos, in 1985, Clapton allowed, “We were a make-believe band. We were all hiding inside it: Derek and the Dominos - the whole thing. I had to come out and admit that I was being me. Being Derek was a cover for the fact that I was trying to steal someone else’s wife. That was one of the reasons for doing it, so that I could write the song, and even use another name for Pattie. So Derek and Layla - it wasn’t real at all.”

Pattie would eventually leave Harrison for Clapton. They were married in 1979, but the union was short-lived and ended in 1989. After the group broke up, Gordon and Radle went their own ways.

“Jim had plans to play with Traffic after our second, failed attempt in the studio,” Whitlock says. “Carl was going back with Leon [Russell]. It was just me and Eric, and I was just trying to wait it out.” And so he did, in vain. “I waited two years for him to come out of isolation, and it wasn’t happening. So that’s when I said, ‘Oh hell, I’m just getting out of here. I’m going back to the United States.’ Sitting there waiting on Eric Clapton to come out of his heroin haze wasn’t very productive for me. I started going downhill.”

It’s great music. And it’s real. It became a success on its own, not because of promotion and not because of Eric Clapton

Bobby Whitlock

Still, 50 years on, Whitlock cherishes his memories of the band and continues to perform songs from Layla live with his wife and musical partner, CoCo Carmel. As for why he thinks Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs continues to resonate with audiences?

“It’s great music,” he says. “And it’s real. It became a success on its own, not because of promotion and not because of Eric Clapton. I remember when we were doing our tour of the United States. We were riding in a station wagon somewhere up in Minnesota, heading to a gig, and ‘My Sweet Lord’ comes on the radio.

“At the time, it was the number-one record in the country. And there we were, four guys in a car, heading to some little gig somewhere. I mean, we were the guys on a number-one record, and nobody even knew who the hell we were!” ‘

- Derek and the Dominos Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs is available on vinyl via Motown Records.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.