“Sometimes you are going to be so frustrated you'll hate the guitar. But all of this is just a part of learning." Jimi Hendrix explains his struggles with guitar in a 1968 Guitar Player interview

Hendrix also discussed problems with his Stratocaster and band mates and offered advice for young musicians

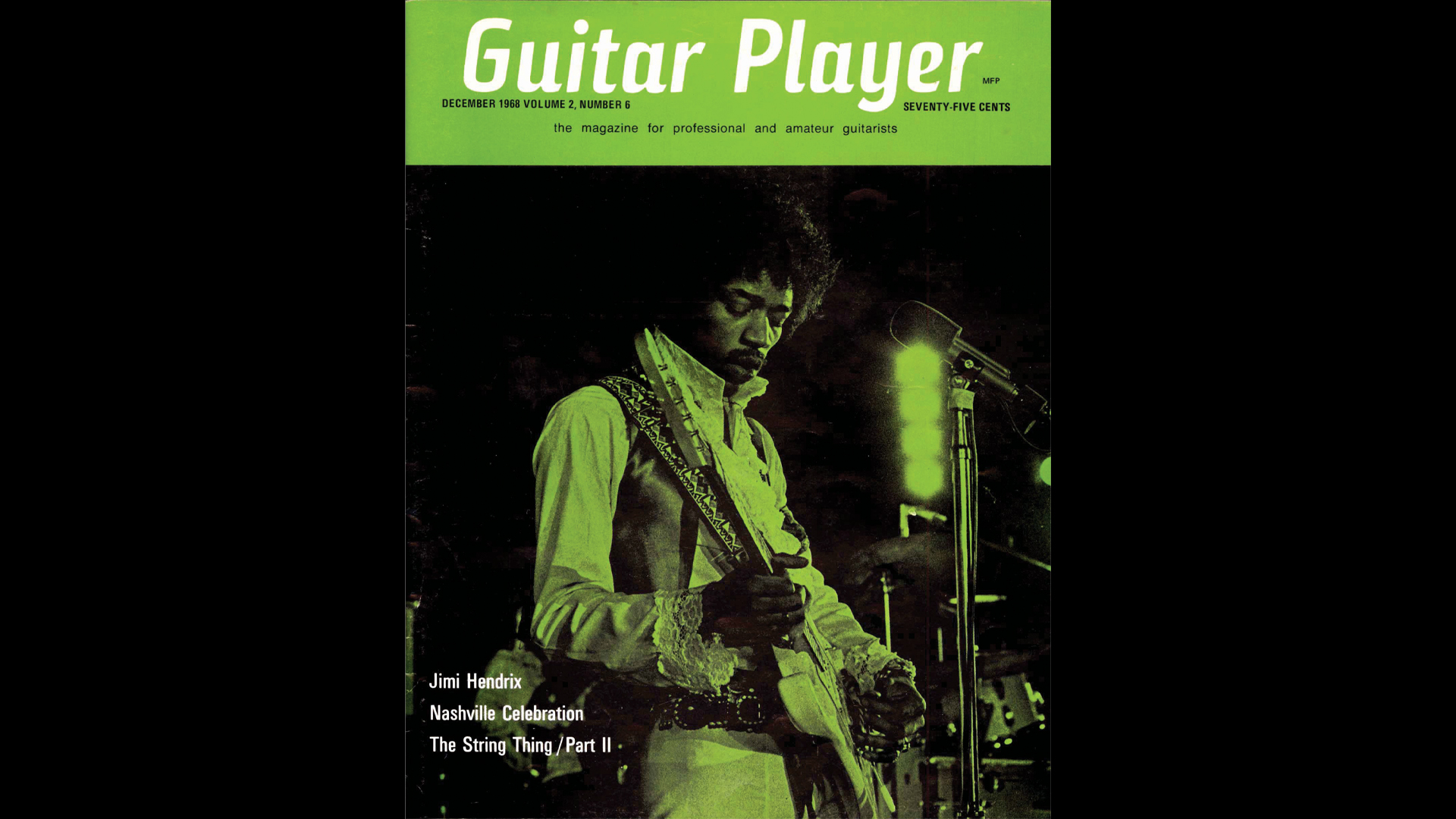

Jimi Hendrix was well into his recording career when he sat down for this interview with Guitar Player, which appeared in the magazine’s December 1968 issue. The magazine was just two years old at the time and still finding its way in the new world it had created for the guitar community. No author’s name appears on the article, and the writer makes no effort to place Hendrix’s career in context by mentioning his albums or titles released up to that time.

Still, the interview makes for fascinating retrospective reading. Jimi offers a window into his frustrations with the Experience — bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell — and his difficulties with the Fender Stratocaster, his electric guitar of choice, while he shares insights into his creative process. It's worth remembering that, at this point, few U.S. readers would have known much about Jimi, let alone his approach to guitar playing and songwriting. Decades on, it remains vital reading.

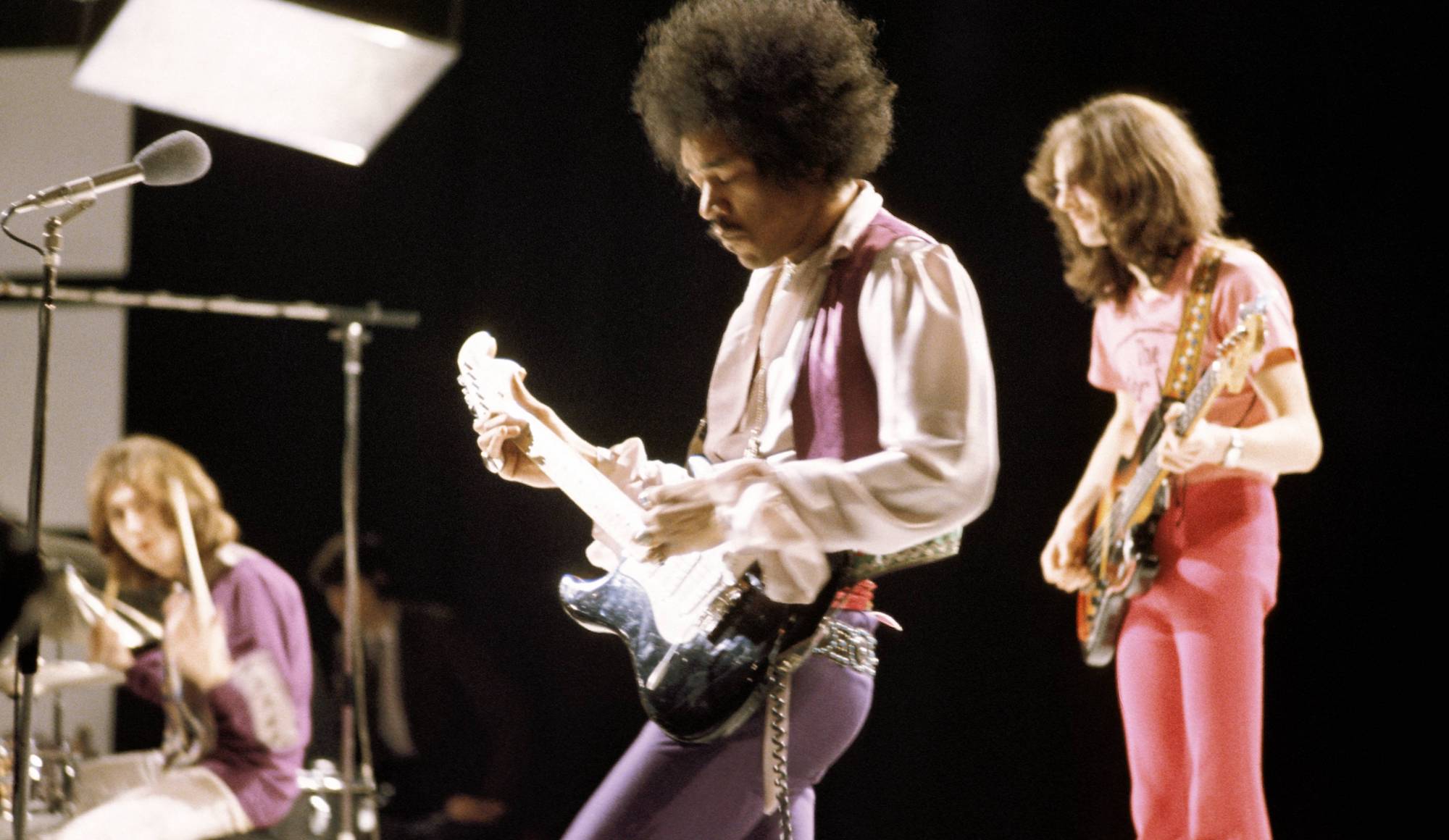

When Jimi Hendrix plays, the house comes down. It doesn't fall in small pieces but in chunks, and the whole place topples on the audience, but it doesn't touch them because he's got them flying up there with him somewhere. That's the way it was at Winterland in San Francisco when we interviewed Jimi Hendrix. That's the way he makes it.

"All my songs happen on the spur of the moment," he says, and he's not handing you a line — you know he's leveling with you. So you ask him if he has to compensate for this spontaneity by using gimmicks.

"On some records you hear all this clash and bang and fanciness, but all we're doing is laying down the guitar tracks and then we echo here and there, but we're not adding false electronic things. We use the same thing anyone else would, but we use it with imagination and common sense. Like ‘House Burning Down’ — we made the guitar sound like it was on fire. It's constantly changing dimensions, and up on top that lead guitar is cutting through everything."

He tells you his most important thing is to communicate with the audience, to communicate with them honestly. His stage presence is usually expected to be sort of obscene, with lots of gesturing, but this is not true most of the time. Jimi's presence is always cool, and he lets his emotions come through strong. At times he has turned his back on the audience — if that's the way he really felt. "When I don't say 'thank you,' or I turn my back to the audience, it's not against them, I'm just doing that to get a certain thing out. I might be uptight about the guitar being out of tune or something. Things have to go through me and I have to show my feelings as soon as they're there."

One problem Jimi has is that his instruments won't hold up. “Like these two guitars I have now, they've been around for a while and they just don't stay in tune. They might slip out of tune a bit right in the middle of the song, and I'll have to start. fighting to get it back in tune. We tune up between every song because it's not a Flash Gordon show — everything all neat and rehearsed — it's not one of those kind of things. It's important for us to get our music across the best way we can. It means we have to do it natural, like tuning up before songs."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Sometimes they might want to tell me something and I might not be able to understand, and it gets frustrating."

—Jimi Hendrix

He tells you about the trio, about working with Mitch Mitchell the drummer and Noel Redding on bass, and how tough it gets sometimes. "Sometimes they might want to tell me something and I might not be able to understand, and it gets frustrating. Anytime you make a song, you want your own personal thing in it as well as the group. We don't compromise with each other very much, you know. Like one guy thinks one thing and he's going to stick with that one thing, so he does it the way he wants it."

Jimi admits the trio doesn't do much practicing. "Most of our practice is thinking about it. They might hear the same tune I have, so they throw it around in their minds and picture the fingerboard. So then, when we go to the studios and I give them a rough idea, maybe Mitch and I will lay a track down completely by ourselves and then add the rest. As far as jamming out here on a show... we try to listen to each other.

"I just keep my music in my head. It doesn't even come out to the other guys until we go to the studio. Sometimes, if I have a new song, or if the guys want to take a vacation or something like that, maybe I'll go to the studio by myself and have an acid tape made and have a rough idea about the drums, guitar, bass and vocal. Then, other times, I'll just come in banging away on the guitar and be singing and say this is a new song. We try to put our own self into it no matter what song we play."

That's how he feels about Jimi Hendrix, but how does a musician look at other musicians?

"When I see a group I look for feeling, not the jump-around kind of feeling... and then I look for togetherness, a communication between the musicians. Originality comes about fourth or fifth."

The night we talked with Jimi Hendrix it was the second anniversary of the trio. Jimi himself was born in Seattle, Washington, 21 years ago. He left school early to join the Army Airborne. "I've played with millions of groups, played behind cats who are making it now."

Jimi feels that those who influenced him while he was trying to make it were Muddy Waters, Elmore James, Eddie Cochran and B. B. King among others. But Jimi's style is not a mixture of the past, it is something which comes out of himself. "I write songs to release frustration. I like to play lead sometimes so I can express myself. But the way I play lead is a raw type of way. It comes to you naturally."

The way Jimi Hendrix plays may be natural for Jimi Hendrix, but it's the opposite of most other guitarists. He plays a backwards/upside-down guitar, holding the neck in his right hand and playing with the bass strings on the bottom and the high strings on the top of the guitar.

"I write songs to release frustration. I like to play lead sometimes so I can express myself. But the way I play lead is a raw type of way. It comes to you naturally."

—Jimi Hendrix

Jimi mostly uses a Stratocaster with Fender light-gauge guitar strings. He also has two Gibsons. "Some of the tracks on our new LP have a Gibson on them." [Jimi would have been referring to Electric Ladyland, which came out in October 1968.] He uses Sunn guitar amps. "It doesn't make any difference what size the amps are as long as I know I have it. I'm not necessarily trying to be loud; I'm just trying to get this impact. I don't like to use mics. To get the right sound it's a combination of both amp and fretting."

He uses light-gauge strings because he doesn't like them to scratch the board too much. Jimi feels it's important not to have a closed mind to new things that are happening. "You can't just get stuck up on guitar; you have to use a little bit of imagination and break away. There's millions of other kinds of instruments. There's horns, guitars, everything. Music is getting better and better, but the idea now is not to get as complicated as you can, but to get as much of yourself into it as you can.

"Music has to go places. We'll squeeze as much as we really feel out of a three-piece group, but things happen naturally. We've got about four tracks that we haven't released yet. One has a very simple rhythm with a funky horn pattern in it, and a tiny bit of echo to make the horn sharper. It happens naturally, like when you hear something you might want to use strings with. But we haven't been able to get these things together because we've been on tour."

You see that there's not much more to ask him, except maybe, that old cliche about what can he say to guys who are still out there trying to make it . . .

"It's pretty hard to give advice, but if these guys have really gotten into it and everyone —mothers and friends — have said 'Wow,' then they should try to get in touch with a major musician or have a representative of a record company come to one of their gigs. But tell them it's best not to sign anything too soon. Tell them to get some lawyers. Managers may not know it all, and a lawyer knows what's right."

"You have to stick with it," he says, "Sometimes you are going to be so frustrated you want to give up the guitar you'll hate the guitar. But all of this is just a part of learning, because if you stick with it you're going to be rewarded."

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.