“It was amazing to see how the crowds reacted to the songs. And it still happens when I play them.” As Bernie Leadon drops his first solo album in 21 years, he talks about the Eagles and the birth of California’s country-rock scene

A pioneer of the West Coast sound that shaped the early 1970s, has lived a rich musical life since departing the Eagles in 1975

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For nearly a decade, it seemed like Bernie Leadon was, as the song says, “Already Gone.”

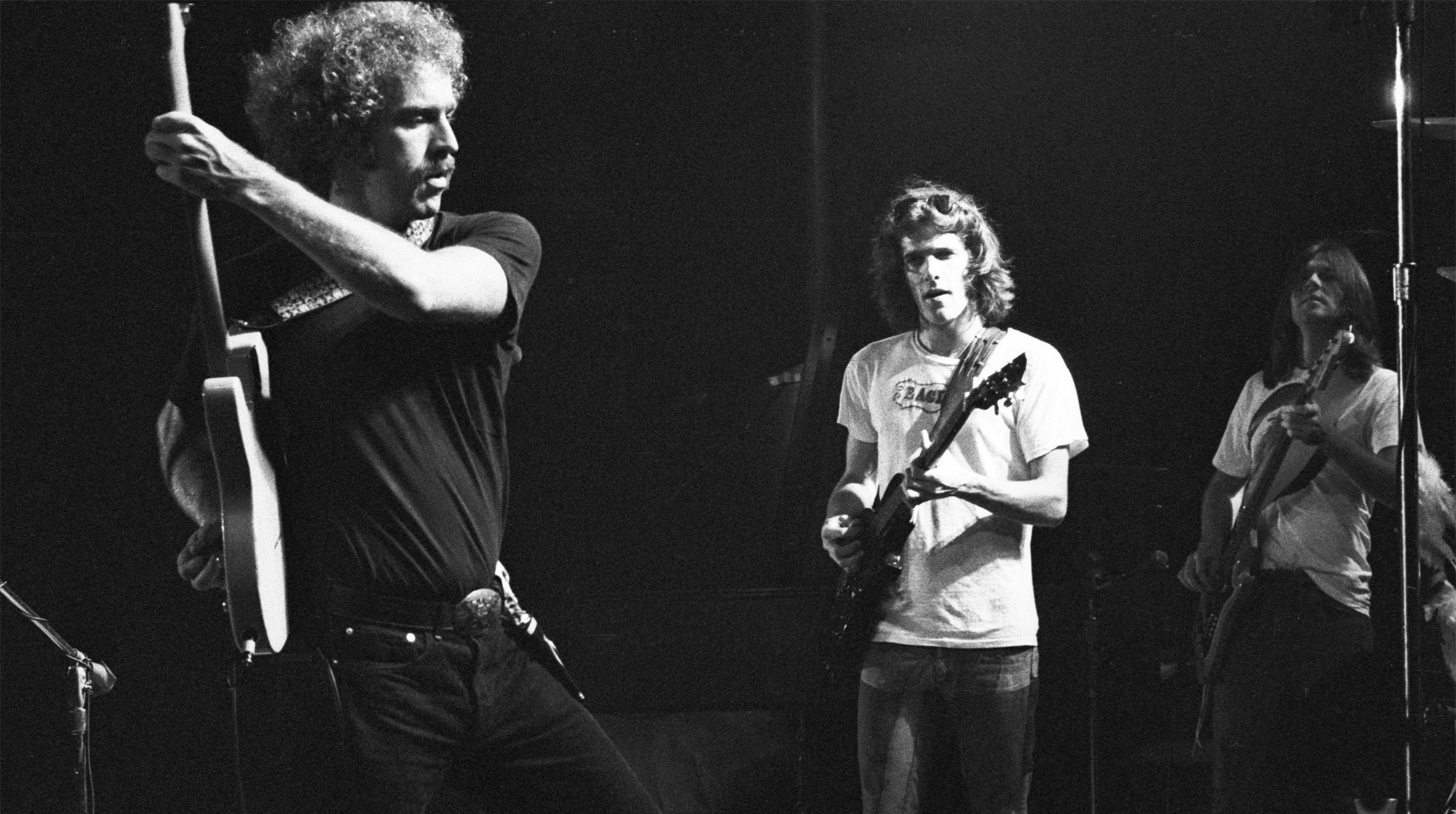

An Eagles co-founder and a Flying Burrito Brothers mainstay, Leadon is one of the architects of the California country-rock movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Back in 2015, the multi-instrumentalist wrapped up his return to the former band and its History of the Eagles tour. It was the year that he appeared on Ethan Johns’ album Silver Liner, and in early February 2016 he rejoined Eagles again to play “Take It Easy” in tribute to Glenn Frey, who’d passed away a couple of weeks prior.

Afterward, it seemed like Leadon had taken it to the limit.

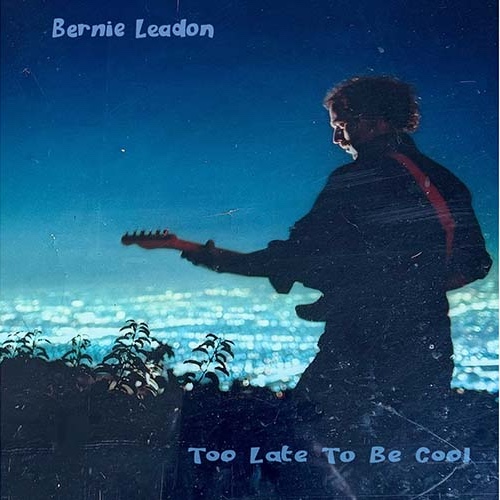

Now, however, he’s taking flight again with Too Late to Be Cool, his first solo album in 21 years. Leadon recorded the album live to tape with original Eagles producer Glyn Johns (famed for his work on the Beatles’ Let It Be and numerous albums for groups like the Rolling Stones and the Who) and an all-star band that includes bass guitarist Glenn Worf, drummer Greg Morrow and keyboardist Tony Harrell. The 11-song set shoots stylistically wide, from singer-songwriter fare such as “Zero Sum Game” to the country-leaning self-deprecation of the title track.

It’s a welcome new adventure in Leadon’s stellar career, one that saw him come out of Gainesville, Florida — where he was friends with eventual Eagles bandmate Don Felder — and then make his way to California, where he played with Hearts & Flowers (including future Burritos mate Chris Hillman) and Dillard & Clark before joining the Burritos in 1969, in time for its sophomore album Burrito Deluxe and the group’s self-titled follow-up.

He moved from there into Linda Ronstadt’s band with Frey and Don Henley, forming Eagles with the duo and former Poco bassist Randy Meisner. Felder tells us that Leadon “can play anything — any instrument with strings, any style of music. His ability is just… supernatural.” And Leadon proved that to be true with his skills and electric and acoustic guitar, banjo, dobro, mandolin and pedal steel.

He departed Eagles acrimoniously after five years and four studio albums, unhappy with the group’s shift toward the rock and pop mainstream and frustrated by a lack of opportunity for his songs. He was hardly wanting for work, however; already an in-demand session player and guest, he appeared on albums by Hillman, Ronstadt, Stephen Stills, Randy Newman, Emmylou Harris, John Hiatt, Alabama, David Crosby, Stevie Nicks, the Jayhawks and scores of others before disappearing into the proverbial long grass.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With Too Late to Be Cool bringing him back into view, we caught up to Leadon via Zoom from his current home near Nashville, to talk about the album and his career of genre creation.

It’s great to have you back. Where’ve you been?

I’ve been writing. The History of the Eagles tour ended in 2015 and my juices were flowing from having been out playing all the time. I built a really nice studio after the tour in 2015 and it’s mostly analog; it has ProTools and digital in it, but it’s, like, an old API vintage console and some tube mics and an old Ampex 16-track, two-inch tape machine. Then I got this engineer nobody’s heard of — Glyn Johns [chuckles] — to come in and record the songs and, dang, it sounded good, so we kept going and finished an album.

Are there things on Too Late to Be Cool that you feel you haven’t done, or haven’t played this way, before?

I got to stretch a bit and just go for solos, which is kind of a new thing for me. I used to always plan and come up with a solo and learn it, and then concentrate on playing it. But I actually just went for some stuff on this record, and I love it.

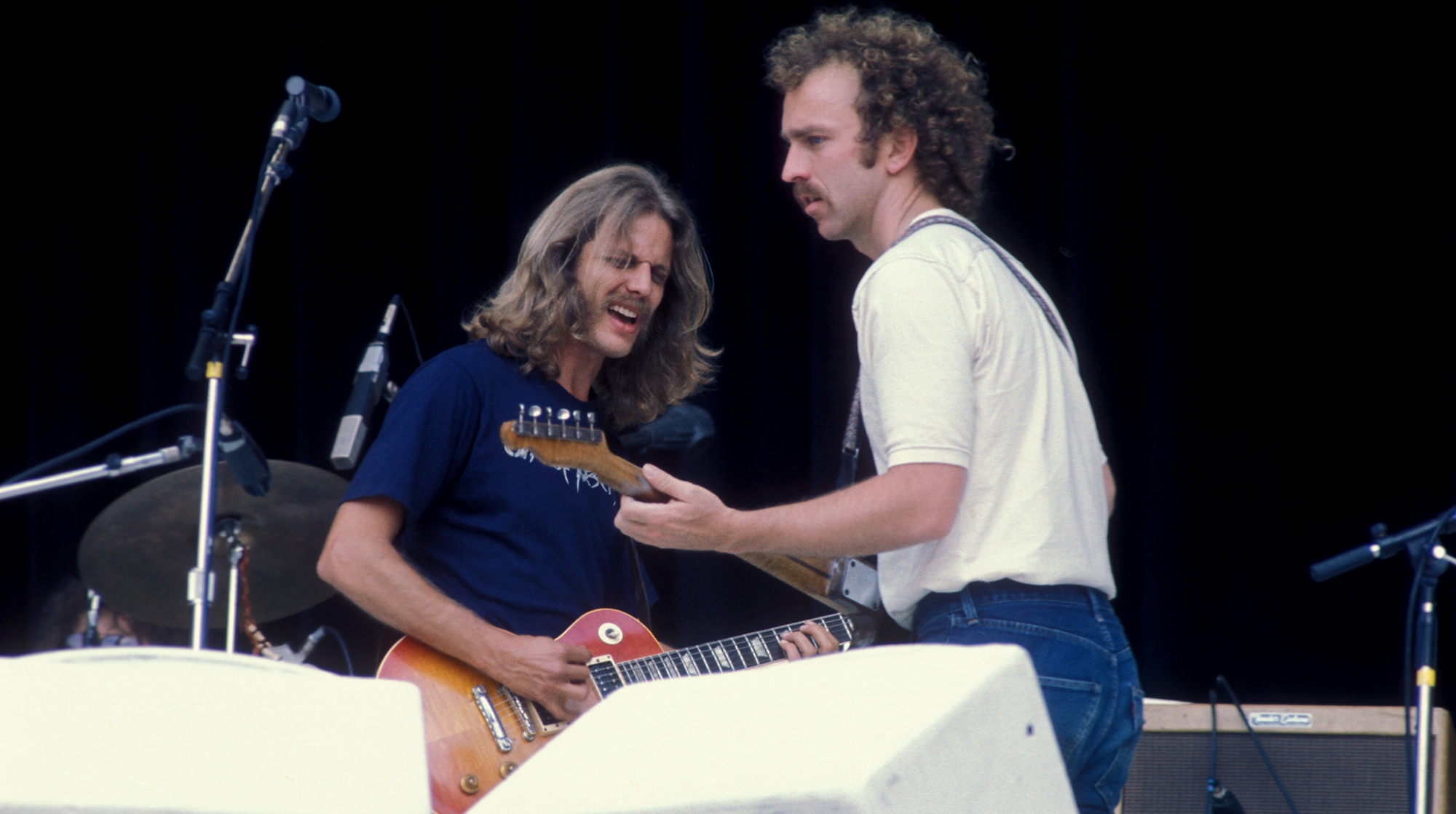

Getting back with Glyn Johns is interesting, since Eagles famously fell out with him while making On the Border. How was it?

I became really good friend with him when he did the albums with the Eagles. He used to have me come stay with him. He had a young family at the time, and it was great to not be in a hotel. Then, when I left the band in ’75, he started using me on other people’s records and flew me over to England or L.A. or wherever.

So I played on a lot of his projects through the years, and we were really tight. We’d come and visit each other, that kind of thing. He knew I’d been building this studio and I’d been writing. I went and visited him during the Eagles tour, in England, and he finally said, “Hey, you want me to come over and mess around and see how it sounds?”

He wanted to help me sort out the studio, and he gave me a list of things — soundproofing to put in the room, drapes instead of packing blankets... that kind of thing. And then we did the album. He works fast. He makes decisions. It was just four players looking at each other in the same room at the same time. We even sang some of the vocals live that are on the record.

It had been a while for you. Was it like riding the proverbial bike?

In a way. I had to relearn how I recorded some of those songs with a flat pick and two fingers, and my muscles were kinda going, “Are you sure you want to do that? You did it in the past, man... come on!” [laughs] But I think I’m a better guitar player, a better singer, a better writer, so that’s fun. It’s fun to be getting better.

Can you talk a little more about the technique. Where does that come from?

Take Doc Watson — his two main styles were flat pick, or he played fingerpicking with a thumb pick, I believe. I’m a banjo player also, so in my early learning to play I took up guitar and banjo — at the same time. I played bluegrass-style banjo with two finger picks and a thumb pick, so I started playing guitar that way back then and emulated Doc Watson’s finger-pickin’ stuff.

But I also played rhythm with a flat pick, and I got into bluegrass slapping, too. James Burton was one finger with a finger pick, but I didn’t use a finger pick. Clarence White, I think, used one or two of his fingers. Because I was a three-finger banjo player, I used flat pick and two fingers, and I could play a lot of banjo rolls with that. I used that on some of the leads in the Eagles stuff, but after I stopped touring with them I stopped playing like that.

And then I evolved this thing where I just dropped the pick and used three fingers and my thumb and then just other things, like beating on the guitar like an early folk singer. They did the strumming with their hand, usually on a gut-string guitar, but I do it on a steel-string guitar. So it was really just combining all these styles.

Sounds like a lot of trial and error was involved here.

You have an idea, I guess, or you experiment with a style. I guess the two fingers with the flat pick was out of trying to do three-finger picking for a minute, but I had to use the flat pick for the rhythm, so that just evolved. I was aware James Burton used one finger pick, but I like the sound of the bare finger, ’cause it’s a mellower tone. You just try something ’til you make a noise that you like, and it sounds good. Then the analyzing comes later, by people who like doing tablature to figure out what so-and-so did.

But I don’t think the person who originated something thought about it in that way; I think they just play. It’s the attitude of jazz singers, how they typically state the theme and then start improvising and doing modulation and all kinds of interesting stuff. There really are no rules, right? You learn the rules so you can learn a structure, and then you break the rules.

How has the approach, or attitude, changed over the years?

I don’t worry about anything too much. Is there a lyrical idea that’s actually interesting, and is there a guitar figure that’s actually interesting? A verse and a chorus and maybe a bridge that fit that don’t jerk you around too much and don’t get too complicated?

Like Tom Petty said once on his Buried Treasure show — he was playing some record and he cut in and said, “Stop changing keys!” We can over-intellectualize anything, but if you’ve got a basic groove and a nice melody and a little lyric that makes sense and is fun, then just have fun with it. If we write something quickly and it’s fun, maybe it has legs and then maybe I’ll still like it in a few months and then maybe I’ll play it for somebody else. It’s not that complicated.

How did you apply that sensibility on Too Late to Be Cool?

I play acoustic on the basics of probably more than half of the songs. There’s this one shuffle — acoustic blues, basically, in E — but it’s kind of a happy little song. The piano player, Tony, and I split a solo; I play first, and also I’m playing hand style, without a pick most of the time, and hitting the guitar with the back of my hand and picking and playing.

The idea when I was writing was I can play the bass line and triads and chords on top and play the lead with enough bass notes so that people know what the chord’s supposed to be, right? For me that’s kind of fresh, playing this hand style. I’m picking a lead and playing the bass note, and then when the piano player starts I just automatically go into, like, a vamp thing. I’ve made a lot of my living as a rhythm guitar player on records, so it’s easy for me to just fall back into the rhythm with the band and not think about it.

Where did that hand style come from?

Well, Stephen Stills was kind of notable as an acoustic guitar player with that early Crosby, Stills & Nash stuff. He also played with no pick, usually, and he used tunings and also a lot of compression; in fact, he used to double compress his acoustics — that’s what the sound of a lot of his stuff was. So I kinda got into that.

There’s a couple things on the early Eagles records that are emulating that. But I have a dear friend named Michael Georgiades who I did an album with in the late ’70s [Natural Progression, 1977], and he plays what he calls hand style, which includes picking and hitting guitar strings with the back of your nails.

So I just experimented with all that, and the idea is to be a little mini orchestra and be able to play enough of the arrangement that’s in my head so it’s basically all present. I really do it just to entertain myself and be able to play what I hear in my head as much as possible. I’ve just kind of evolved it. It’s still good to use a pick sometimes, especially for the rock songs. It’s just fun to try different things, right?

Was it country first for you and then rock? Vice versa? Both at the same time?

I started in folk music, and folk banjo — before it was anything other than folk music. Then I discovered better players, like Doc Watson or Earl Scruggs on guitar and banjo, and learned more complicated playing.

Then I learned country stuff. I got a Telecaster, but before that I learned country lead, per se, when I was in a Top 40 band with Don Felder in Gainesville, Florisa. We learned all the hits of the day, which was a lot of fun. I learned Stones songs. I learned Chuck Berry songs, and interesting bands like the Yardbirds.

So that was a real education about styles and how to play rock and roll rhythm, especially the Chuck Berry rhythms. There’s just so much stuff in my brain from all those different eras and styles, so when I write stuff it just kind of comes out as needed, to fit the mood on the table.

Did that help make the fusion of country and rock more organic?

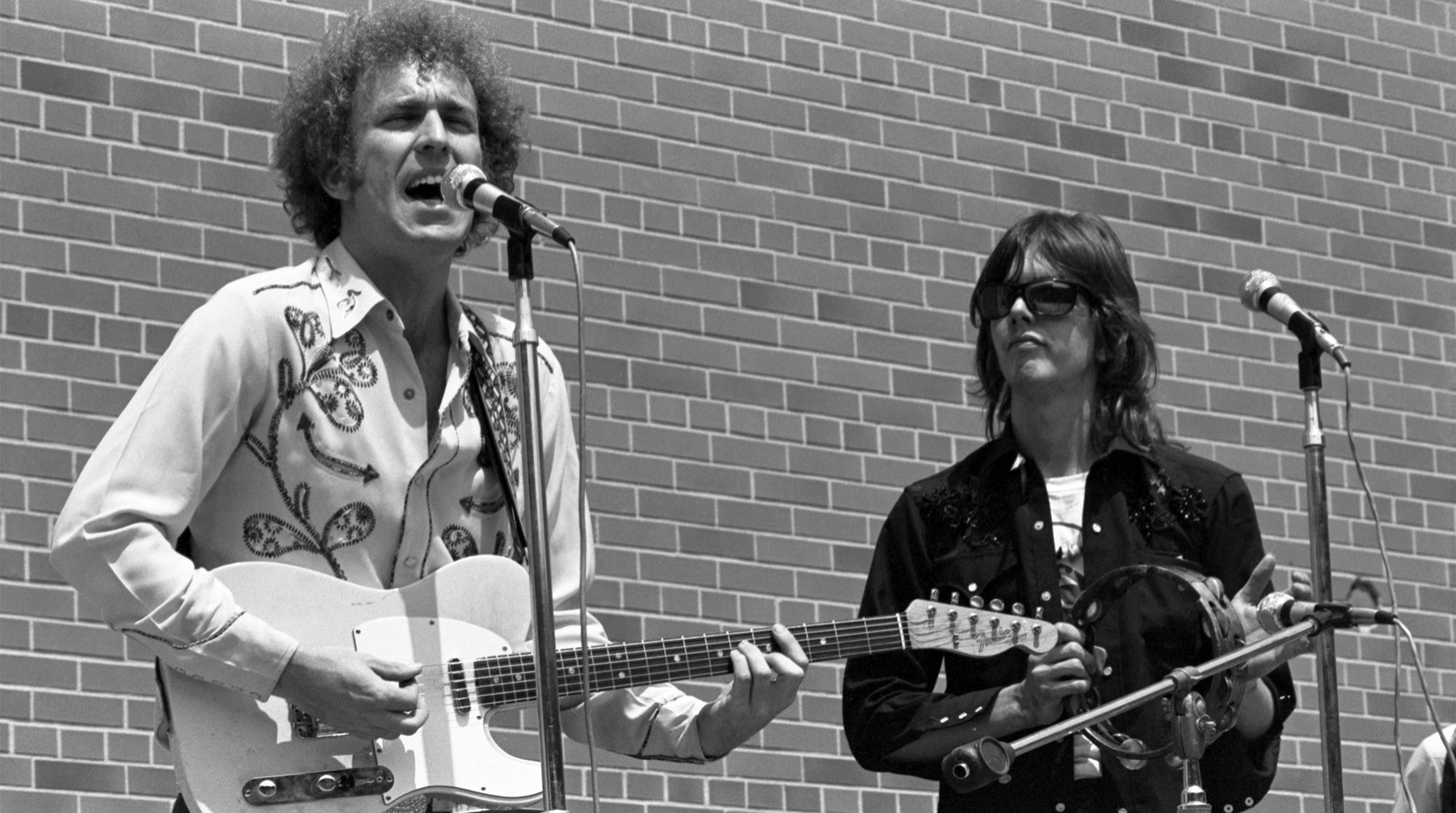

It just kind of evolved. I was in Dillard & Clark — Doug Dillard the banjo player and Gene Clark from the Byrds, and he played acoustic guitar, mainly. We would jam songs and then Gene would come back the next day with lyrics, and it was his very interesting lyric abilities and melodic abilities with the banjo-guitar stuff that brought those styles together.

Near the end of that band, before it broke up, we were changing to electric instruments and I was trying to play Telecaster-type country stuff. Then the band broke up and the Burrito Brothers asked me to join, so now I had to do the Tele stuff to much more hardcore country tunes and arrangements. We listened to Merle Haggard a lot at that time.

What did you get out of those?

There were a couple Merle albums that were James Burton, one of my heroes, on guitar and whoever was in his house band. I found out later that Merle Haggard played guitar on a lot of stuff, too. And I just absorbed more of that stuff.

But the country-rock synthesis just came about organically, and when the Eagles started we just explored it more. And the Burritos had brought in classic R&B to mix with the classic country. Around that time Ray Charles came out with his country album, and that showed you could do it another way, too; you can take a country song and a great R&B artist could do it.

The boundaries between genres are kind of artificial, really. The musicians don’t see it that rigid. The stores needed different bins to put different records in, so they came up with genres — “That’s country. That’s rock. That’s R&B. That’s bluegrass.” I don’t think musicians see it that way. We don’t worry about classification.

There’s probably a bit of a mental hurdle to get to the point where you don’t worry about it, just do it.

Yeah, exactly. The Eagles evolved through a lot of different stuff, right? You could say the One of These Nights album, which we recorded in Miami, Criteria Studios — where the Bee Gees recorded — is the Eagles’ disco album, really. It kinda sounds like it, now; when you hear “One of These Nights,” it’s a disco song, man. Even the background vocals, way up there.

So the Eagles evolved through a lot of styles, especially from the beginning. That’s just how somebody wanted to do it. That’s what somebody was writing, and the marketplace, luckily, went along with us.

That may be an understatement.

What was amazing was to see the crowd and how they reacted to the various songs... and it still happens if I play those songs. The fact the songs mean something to people, and maybe they got married to that song or that song was when they were dating and who knows what life event.

That’s really significant to me. The songs become married to individual people when they’re living their lives, and they held on to them. And the general feeling is almost like, “Why me?” I know we all had the intention to do this when we were young, to do well and be successful, but it’s pretty amazing it did come true.

You mentioned the Telecaster earlier. How did that become such an important guitar for you?

Y’know, a Stratocaster has cut-outs in the back, and it’s actually uncomfortable to sit it on your lap, ’cause it doesn’t have a flat side on the bottom. A Gibson Les Paul has a carved top, so it’s not exactly flat like on an acoustic guitar. But a Telecaster has a flat slab front and back, and it has a flat bottom so you can put it on your leg. It’s quite comfortable for an acoustic guitar player to pick up and play. And then the tone being bright, it was a little bit like a banjo. It just felt comfortable to me.

What was your first Telecaster?

Luckily, early on I stumped into ownership of a 1953 butterscotch Tele, and that guitar just suited me to a T. So I’ve played that particular guitar ever since. And I’ve cut up some ones that weren’t as valuable as that one to put on B-benders and that kind of thing. A lot of the stuff I did in the early Eagles wasn’t B-bender pull strings, actually; it was finger bends.

Which instrument in your collection has the coolest story?

I’ll mention the guitar that I played on everything, from when I went to L.A. in August of ’67 and started recording until after I left the Eagles. It was a 1966 Brazilian rosewood Martin D-35; I bought it new in a store I worked in at the time in Gainesville and I broke it in.

I don’t know why it sounded better than a D-28, but it did. The whole body’s a little thinner in the dimensions of the wood. It has a bound neck, and I played that because that’s all I could afford was that one guitar. I had to sell a ’64 Gibson 335 to buy my first Tele ’cause I couldn’t afford both. That’s how it is when you start. I just had instruments that were my journeyman tools, and I used those for most of my career. Then later on, when I had a little money, I could buy a collective one or two.

You’ve played with so many people over the years—in your bands, in sessions. Who sticks out the most?

I guess maybe I’ll mention that maybe my favorite Tele players over the years were James Burton and Clarence White on the country side, and then Steve Cropper and Jesse Ed Davis on more of the bluesy or R&B side. Jesse Ed Davis could play all of it; he could play R&B, blues, country, everything. All of those guys had tremendous tone, and they were just tremendous players, all of them.

And I love a good rhythm section; a good bass player’s super important, so I played with a lot of good ones, and I think Randy Meisner was underrated as a bass player. Like you say, I played with a lot of people... and a lot of great ones.

Is there anything you’d still like to do, musically, that you haven’t yet?

No. I’m singer/songwriter/guitar player, basically. I’ll stick to those nuts and bolts. Stylistically I’m driving around more, and I like that. But there’s not anything stylistically that’s like, “I wish I could do that.” I’m not a jazz player, per se, but I can appropriate things from jazz. And I don’t want to become a jazz player; I think it’s probably too late to get that good with it, anyway, to learn the whole jazz songbook. That’s really not something I want to do, but I do love jazz.

Has experience, or age, made you braver and more confident when you step up to do something?

[laughs] Yeah. Actually, Glenn Worf accused me of being brave after we did the song on the new album about dancing in the kitchen with Ella and Frank [“Everyone's Quirky”]. It was a challenging acoustic guitar part, with a bunch of sections, so it’s just a little unusual.

And he accused me of being brave. I hadn't really thought about it that way, but that one took us about four hours to get, where most of the songs were first or second takes. But I love the whole thing. I think the quality of the songs is good and the performances are great, by those guys particularly.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.