All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Even a cursory glance at producer/engineer Ken Scott’s resume is bound to fill someone with a sense of awe. Among the iconic artists he’s worked with are the likes of the Beatles, Elton John, Jeff Beck, Lou Reed and Harry Nilsson.

During the early ’70s, Scott was the go-to man behind the console for the crème de la crème of British rock royalty.

George Harrison tapped him to engineer his classic All Things Must Pass, and John Lennon followed suit for his Imagine album.

Astonishingly, if one were to have told Scott in 1972 that a half-century later he would be reminiscing about any of the albums he was recording, he would have laughed his head off.

“I think I would have found the whole thing ludicrous,” he says. “We never thought anything we were doing had any kind of longevity,” he says. “It’s not that we didn’t think the music was any good; it’s just that we were constantly moving on to the next thing.”

We were constantly moving on to the next thing

Ken Scott

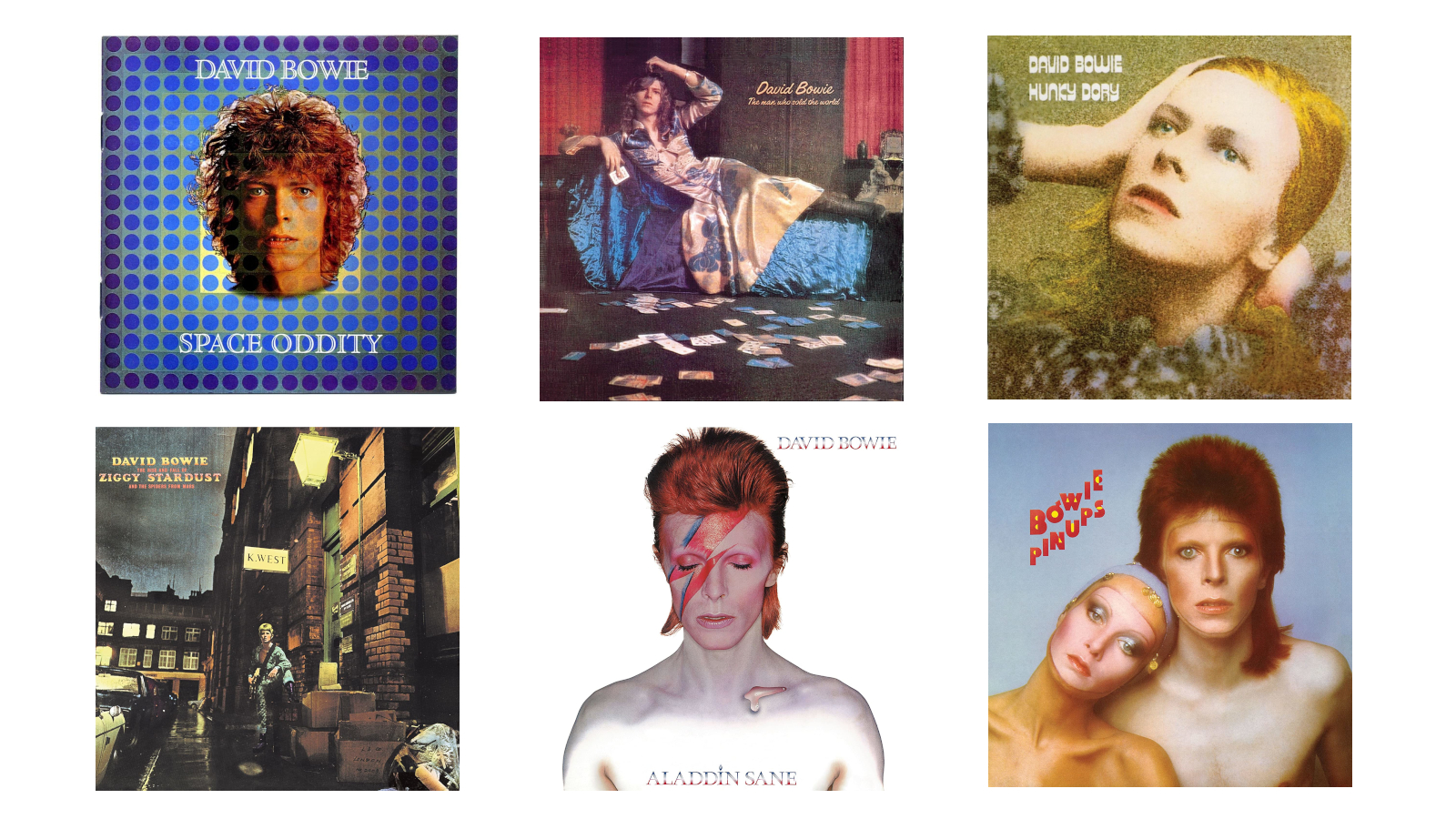

Among the records Scott had a hand in during those heady days of the early ’70s are four epochal (and star-making) David Bowie albums that he engineered and co-produced with the singer-songwriter: 1971’s Hunky Dory, 1972’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, and 1973’s Aladdin Sane and Pin Ups.

Viewed in the rearview mirror, the variety of musical styles that mercurial artist flirted with, absorbed and even pioneered on these records – there’s folk, dancehall, pop, art rock, glam, garage rock and proto-punk – now feels nothing less than remarkable.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But as Scott recalls, “The idea that we were doing something historic never entered our minds. Back then, recording contracts called for two albums a year. When we made a record, we thought, If this lasts for six months, then we’ve done our job correctly.”

Back then, recording contracts called for two albums a year

Ken Scott

Scott got his start at the age of 16 as a lowly tape logger at London’s EMI Studios and gradually rose through the ranks to second engineer and then full-fledged engineer, manning the board for the bulk of the Beatles’ sprawling 1968 self-titled double album.

He first worked with Bowie on the albums Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World.

“Quite honestly, I didn’t see David’s talent at the time,” he says. “I thought he was a really nice guy who obviously had a certain amount of talent. But from what I’d seen on those two albums I did with him as an engineer, I didn’t think he had it in him to be huge.”

Scott had yet to produce a record on his own, and he was itching for an opportunity to jump into the big leagues.

Ironically, that invitation came from Bowie, who had asked him to engineer a session that the singer was producing for his clothing-designer friend, Freddie Burretti, whom Bowie hoped would become “the next Mick Jagger.”

“Being British, we were taking a tea break in the studio,” Scott recalls, “and I mentioned to David that I wanted to start producing.

“That’s when he said, ‘Well, I’ve just signed a new management deal. They want to put me in the studio to record an album so they can shop a record deal. I was going to produce it myself, but I don’t know if I’m capable. Will you co-produce it with me?’”

It was an enticing offer, but Scott was still unsure that Bowie had the goods in him. However, his mind changed a few weeks later when the singer played him demos for what would be his next album.

“At that point, I suddenly realized there was a hell of a lot more to him that I’d heard from the previous two albums,” Scott says. “And it was then that I realized that he could be huge.”

I suddenly realized there was a hell of a lot more to him that I’d heard from the previous two albums

Ken Scott

From the outset, Scott adopted a “let David be David” ethos in the studio, which he says was a stark contrast to the production style of the singer’s previous co-producer, Tony Visconti.

“Tony was the bass player, the arranger and the producer, and I didn’t get the feeling that David had much say,” he offers.

“It was David’s songs and his vocals. He had a certain amount of input, but it didn’t go that far. I learned a lot from watching people like [producers] George Martin and Gus Dudgeon. They both had the mindset of ‘the talent is put in the studio to create, and you have to allow the talent the freedom to do that,’ knowing that you can always pull them back if they go too far afield.”

Hunky Dory was Scott’s and Bowie’s “getting to know each other” album, and as Scott notes, “We both went in with a lot of fear, because neither of us had really done what we were about to do. But as things started to happen, we gained confidence, and of course, David had some wonderful songs.

“As we worked together, we started to push the envelope a little further, and we saw that things were working, so we kept at it over the next few albums.”

As we worked together, we started to push the envelope a little further

Ken Scott

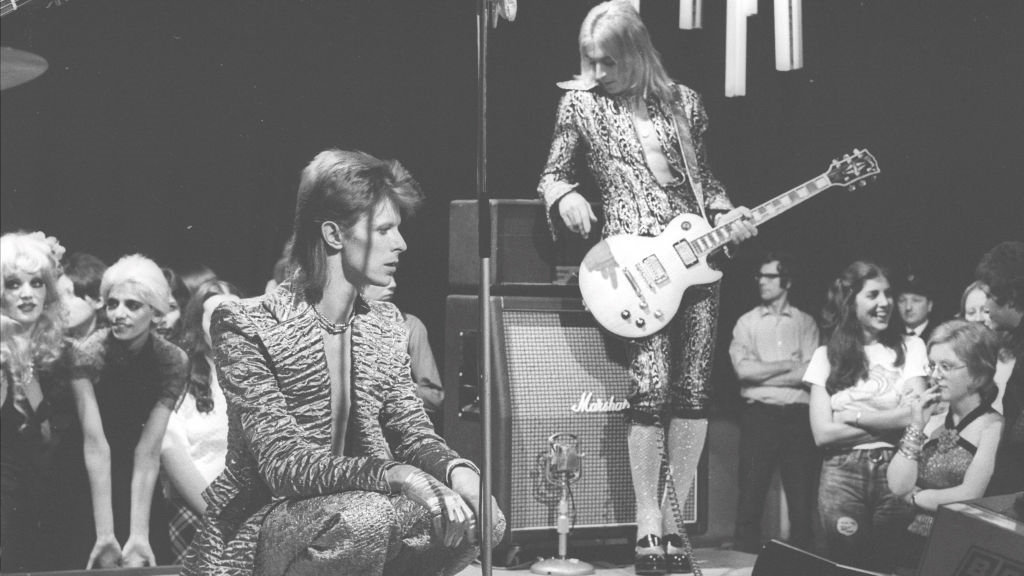

It also helped that Bowie brought with him an ace band, the Spiders from Mars, consisting of bassist Trevor Bolder, drummer Mick Woodmansey and guitarist Mick Ronson, the latter of whom would soon become the singer’s flashy onstage foil and main studio sound architect.

“I already knew Ronno and Woody a little from their playing on The Man Who Sold the World, and I knew they would work perfectly,” Scott says.

“They were easy to work with, very professional and fun. Ronno was definitely the band leader when one was required, but generally the guys just knew what they had to do and what was needed.”

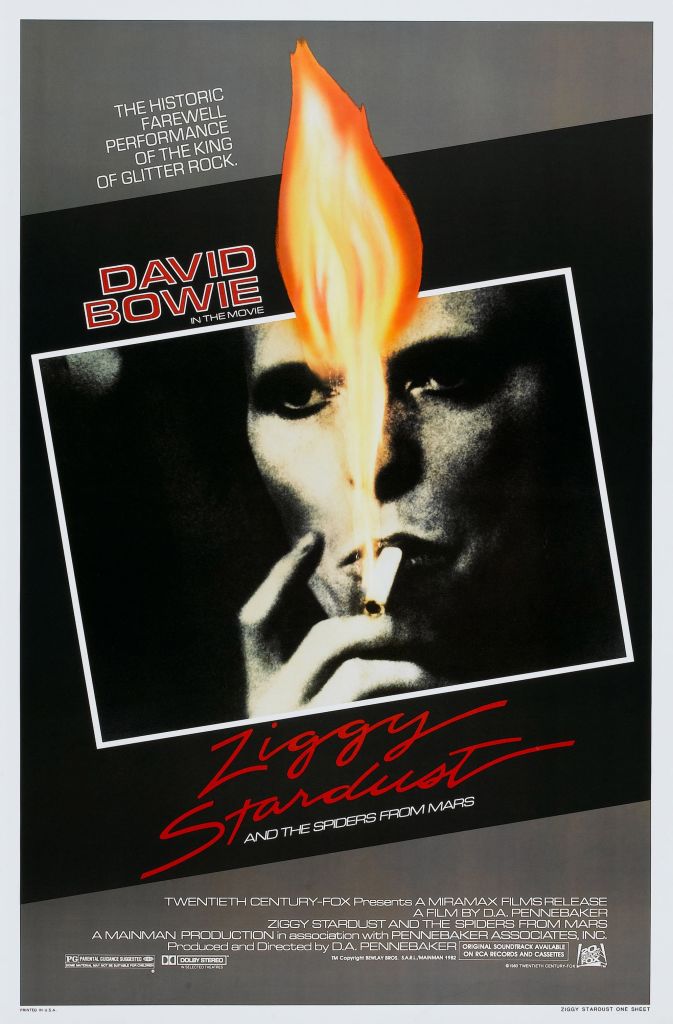

Ziggy Stardust is viewed as one of rock’s great concept albums, but you once said that it didn’t start that way at all.

I don’t think there ever was a concept to it, but somehow that became applied to the record. People find small things to put a story together.

One of the mainstays of the whole concept album thing is the track “Starman.” Without that song, the whole concept falls apart.

Originally, we had Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around” in that place. It was only when RCA said they didn’t hear a single that we went back in and recorded “Starman.” Had that not happened, the concept idea would’ve been out the window. They wouldn’t have had anything to pin it on.

It was only when RCA said they didn’t hear a single that we went back in and recorded ‘Starman’

Ken Scott

Generally speaking, how did David present songs to you? Were they demoed? Were some cuts written in the studio?

Some songs were demoed, but nothing was really written in the studio. I remember on Hunky Dory, “The Bewlay Brothers” was the last track that we did.

It came together in the studio, but it wasn’t written there. David came in toward the end of the recording and said, “We’ve got to do one more track. I’ve got this song, but don’t listen to the lyrics.”

Some songs were demoed, but nothing was really written in the studio

Ken Scott

I asked him why, and he said, “Because they don’t mean anything. I just wrote it for the American market to see what they would read into it.”

This was during the “Paul is dead” period. David picked up on how people in America were reading into things that weren’t there, so he came up with lyrics specifically for that kind of thing, to see what would happen.

Over the years, I’ve heard many different interpretations of what it’s about, and I’m sure David agreed with all of them.

Was David generally efficient in the studio?

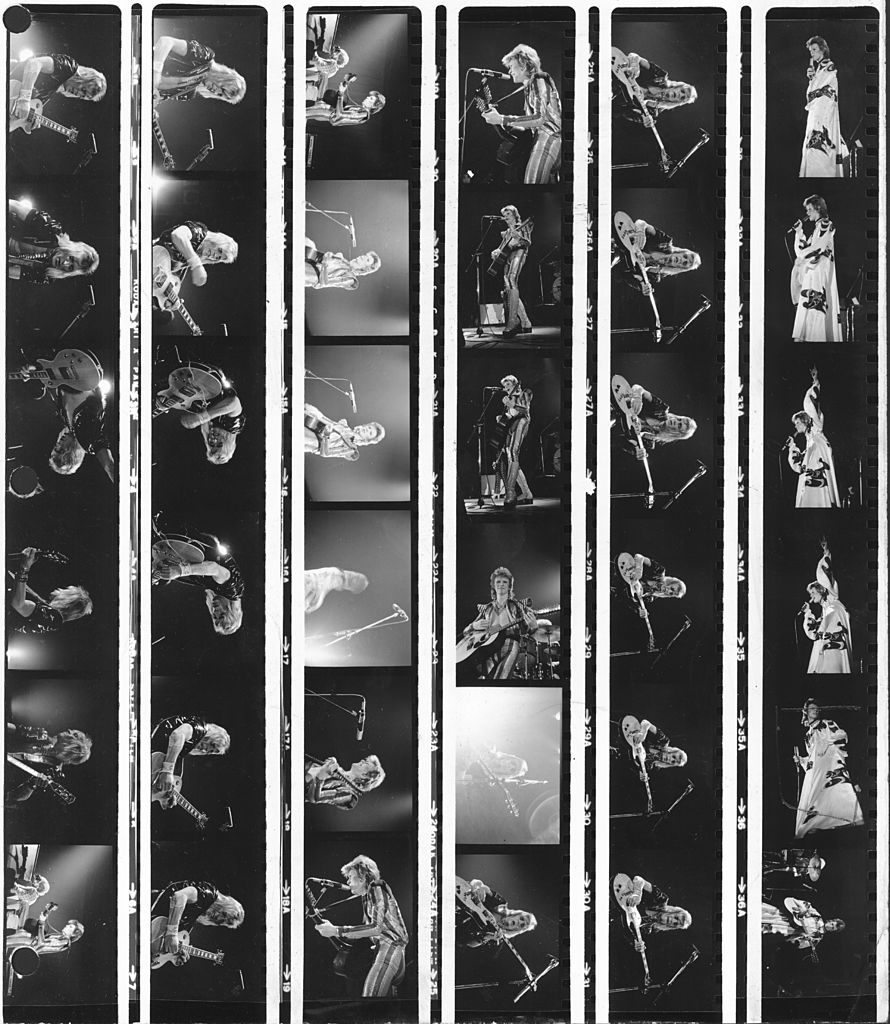

Are you kidding? [laughs] He petrified Woody, Trevor and Ronno. They were always on edge, because they always felt if they didn’t get the track quickly, David would just say, “It’s not happening. Let’s move on to something else.”

Bear in mind that, vocally, he was absolutely astounding. Of the four albums I co-produced with him, 85 to 90 percent of the vocals were first takes from beginning to end.

Of the four albums I co-produced with him, 85 to 90 percent of the vocals were first takes from beginning to end

Ken Scott

I would run the tape a little just to get him to sing so I could get the sound levels, and then once I hit “record” to get a real take, he would nail it.

A lot of those performances are what you hear today. He didn’t hold back. On the song “Five Years,” by the end of the take, he was bawling his eyes out. Tears were rolling down his face. He was amazing.

How was David’s relationship with Mick Ronson as guitar players? Did he give Mick guidance as to what he wanted, or did he let him come up with his own parts?

The feeling that I got – or I get in hindsight – was that David was very good at picking teams. He looked for people who could give him exactly what he was after without necessarily telling them what he wanted.

He would show them the song, and then people sort of worked out their own parts. But it usually would be exactly what he wanted.

David was very good at picking teams. He looked for people who could give him exactly what he was after

Ken Scott

There might have been times when something would’ve been said, but most of the time it was left up to everyone to sort of come up with their own parts.

With me, David never came to the mixes. He would leave me to get on with it and do what I did best.

What were your feelings about Mick as a guitar player?

Oh, he was great. He was also quick – one or two takes. Then we’d listen and decide what should be doubled or harmonized. He knew what a song needed.

Quite often I’d say, “Okay, Mick, it’s time to –” and he would say, “I know, the solo. I’ll do it right now.” And he would do what was needed right away.

David played a lot of acoustic guitar in the studio, but did he ever play electric?

I don’t remember David ever playing electric guitar, but there were times when Mick would play acoustic guitar.

What kinds of guitars would Mick bring to the studio? He liked his ’68 Les Paul Custom.

It would always be his Paul, his Marshall stack and his Cry Baby wah.

With the wah, he would park it to the one setting and leave it there, which made things very easy for us in terms of finding a sound. There was none of the messing around with the amp.

Keeping the wah at one setting gave him more of a unique sound because it was more compact. He just sounded different from everybody else who would go in and turn up loud.

Keeping the wah at one setting gave [Mick Ronson] more of a unique sound

Ken Scott

On Ziggy Stardust, there’s a great marriage of electric riffs and solos with the sound of acoustics. Was that combination ever discussed?

It wasn’t discussed, really; it was just understood: “This is the sound for this song.”

For me, the acoustic thing served two purposes. All of those old rock and roll songs by Eddie Cochran, Presley, Bill Haley – all those guys – they had acoustic guitar on them. To get that early rock and roll sound, we needed acoustics.

There was that, but something I didn’t realize was how they took the place of cymbals. During that period, I didn’t like cymbals, so I would tend to keep the overheads down on the drums, but I also had a very bright sound on the acoustic, and that sound covered what cymbals would normally do. At the same time, we got a totally different feel than what cymbals would have achieved.

You have that mix of acoustics and electrics on “Suffragette City,” which is now seen as a proto-punk song. The solo is one of Mick’s best. Did he just pull that out of the air one day?

Probably. Like I said, he was very fast. We had two weeks to make an album, so we had to do everything quickly, including solos. We didn’t micromanage anything.

We had two weeks to make an album

Ken Scott

Now Mick wasn’t just the guitar player; he did the string arrangements too.

He did. He was great with that. He had his way of doing things. He’d work on arrangements the night before a session, and apparently he would fall asleep before completing his work.

So he would run into the studio, lock himself in the bathroom and complete it there. Twenty minutes would go by, and he’d come out with a stack of music paper. He’d go into the studio and hand it out to the musicians.

At the point when you recorded Aladdin Sane, David was a star.

[laughs] Yes, very much so.

Did you notice any changes in him that made working with him different?

Working with him? No. There was a change, I think, for both of us: We’d gained confidence. Obviously, when you’re working on something and then it’s suddenly successful, that gives you a lot of confidence to try other things. But we basically worked the same.

The weirdest thing for me was recording some of the stuff at RCA in New York, because the studio was heavily unionized

Ken Scott

The weirdest thing for me was recording some of the stuff at RCA in New York, because the studio was heavily unionized, and I had to play the typical producer, sitting at the end of the desk. I wasn’t allowed to touch anything.

I remember once when I pushed a button on the desk while the engineer and assistant engineers were out eating: I was just trying to make sure the band could hear themselves on their headphones and rehearse the next track.

When the engineer came back, he hit the roof. I could have taken the entire studio out. Everyone could have gone on strike because I pushed one button.

Aladdin Sane is a tougher-sounding album than Ziggy Stardust.

It is tougher sounding, and I think that’s a result of the band touring the States. It changed them in certain ways. They got a bit heavier and grew some balls.

It was recorded very much the same way as the others; we just went in and did what we did. But yes, David’s songs were heavier because of the American influence.

It’s there in “The Jean Genie,” which uses Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man” riff as it was interpreted by the Yardbirds, but in a bluesier style.

Absolutely. David was picking up on all that stuff.

It’s not like nowadays, when people take two years to make a bloody record. They micromanage every single eighth note or whatever

Ken Scott

Because the band was touring so much, was it harder for you as a producer to get everyone’s attention? Their world was now moving a lot faster.

In some ways, but as I’ve said, we just went into the studio and did what we did. It’s what we knew. We didn’t think about the time frame. It’s not like nowadays, when people take two years to make a bloody record. They micromanage every single eighth note or whatever.

Do you remember what brought about the cover of “Let’s Spend the Night Together”?

Not really. David always liked to do covers. I guess he wanted to do a Stones song because of his friendship with Jagger.

You recorded a few amazing songs that didn’t make Aladdin Sane. There was “John, I’m Only Dancing.”

That was a very strange one. There are so many different versions of that, some of which I was part of and some I wasn’t. But they’re all almost identical.

David always liked to do covers

Ken Scott

There was also “All the Young Dudes.”

Oh yeah. I really enjoyed that one, but it just didn’t work for the album. That happens. When I worked with Supertramp, we had the song “Breakfast in America” for their Crime of the Century album, but it didn’t fit the record. It came out much later [as the title track] on what became their biggest album.

Finally, there’s Pin Ups. Is it fair to call that kind of a “stop-gap” album?

I think so. That was a strange one in many respects because David had just fired two members of the band: Trevor and Woody. In that respect, there was a lot of ill feeling.

The bass player who was originally supposed to be playing on the album pulled out at the last minute, so David had to go back to Trevor and say, “Will you play bass?” After you’ve just fired the guy, that’s a very hard thing to do. You can imagine how Trevor felt about it.

Ronno, I think, was in a difficult place because he knew that he wasn’t going to be doing much more with David

Ken Scott

Ronno, I think, was in a difficult place because he knew that he wasn’t going to be doing much more with David.

Tony Defries, their manager, had said to Mick, “I’m going to make you a star just the way I did David.” Which was bullshit. Defries just wanted all of them out of the way, because they had threatened a strike when they were going over to Japan.

With Mick being fired before the start of the record, was he harder to work with?

He was fine. He was good. It was a very strange album, because things were changing and had changed.

My wife was going to give birth to twins while I was in France. I flew back the night before, but I still managed to get to the hospital late, after she’d already given birth. There were distractions for everyone.

Outside of the studio, did you and David socialize much?

We did, but not often. We were generally too busy.

As you were finishing Pin Ups, was there any indication where David was headed next?

Not at that point. It became more obvious a little later, because I continued working with him a little.

There was something called “The 1980 Floor Show,” which was for [NBC’s] The Midnight Special. I did that.

The musicians were so totally different, but he was after the American feel

Ken Scott

Just before we recorded it, there were two songs that David had put together that were on Diamond Dogs: “1984” and “Dodo.” They were one song.

That was one of the few times that David came to a mix, and he kept on putting on Barry White. It was sort of a Philadelphia soul-type sound. He kept on reverting to that, saying, “I want it to sound more like that.”

We could never get that, because the musicians were so totally different, but he was after the American feel.

He was getting into soul and funk, but certainly not the electronic music that he would help to pioneer later in the ’70s.

Oh, no, no. That certainly came about much later. But it was that shift to what he would call “plastic soul,” and that started to become obvious.

That was the last time I worked with him. There was that track, and then we did “The 1980 Floor Show,” and then we never worked together again.

Browse the David Bowie catalog here.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.