“I didn’t want to be the flashy lead player. Whether it was Keith Richards, Pete Townshend, David Crosby or Richie Havens, what the left hand was doing was more fascinating to me than what the right hand was doing": The Paul Stanley interview

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

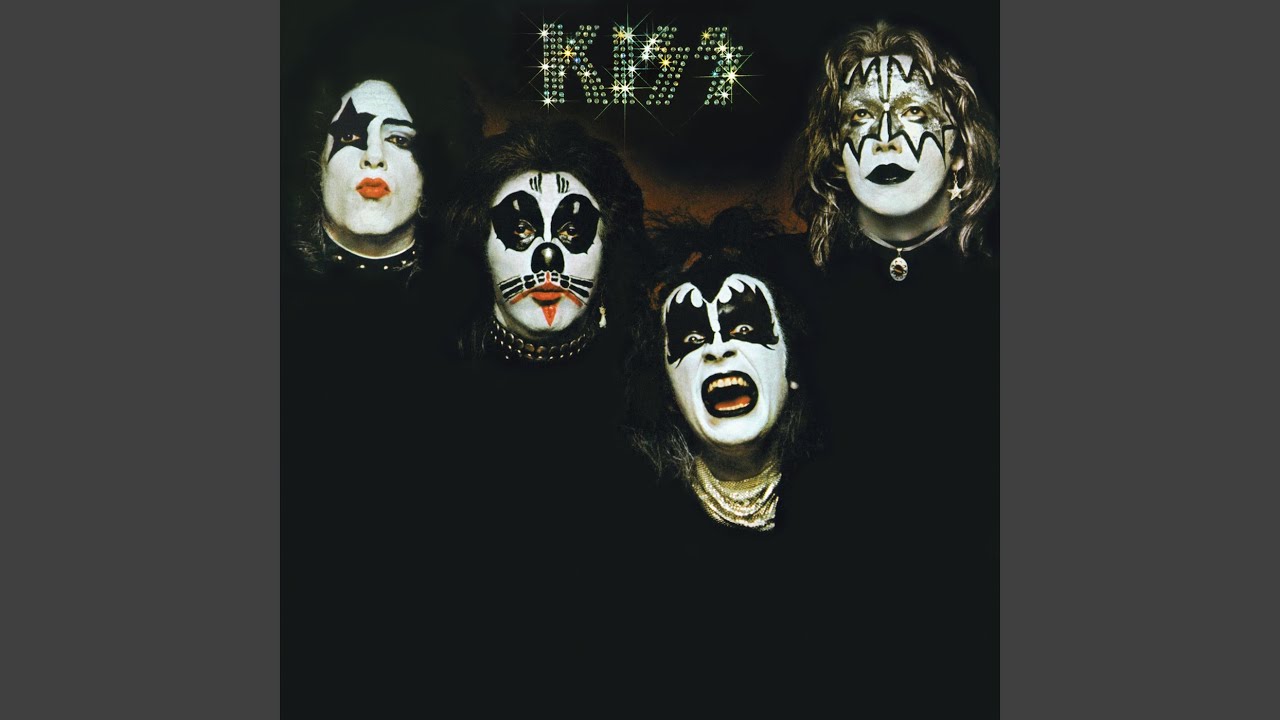

"We wanted to be a band that had heavy guitars but also songs with strong melodies and choruses. That’s the school I grew up in,” Paul Stanley says, reflecting on the birth of Kiss, the group he co-founded some 50 years ago. “It was coming more from the Brill Building kind of writers than headbanging.

"The idea was to combine some of the old Tin Pan Alley sensibilities with the Beatles’ style of songwriting and make it more guitar-driven, like Led Zeppelin, or the Rolling Stones and the Who. Interestingly, most of it was about rhythm guitar, which is the foundation of everything. Without it, everything falls apart.”

From humble roots in Queens, New York, through equal measures of talent, ambition, hard work and self-belief, Paul Stanley willed himself into becoming a rock star. His Kiss persona is the Starchild after all, and he’s been championed as one of rock’s greatest frontmen. In concert, he’s part game-show host, part gospel preacher, espousing the life-affirming spirit of anthemic, fist-waving rock and roll thunder.

Article continues belowMore than most guitarists, Stanley embraces his vital role as a rhythm player. Think of him as the bastard child of Keith Richards’ raucous riffery, the arena-rock power-chord majesty of Pete Townshend and the boogie-rock splendor of Humble Pie’s Steve Marriott.

And like all three of those guitarists, Stanley has taken to the task with a mixture of swagger and attitude. His rowdy rhythms and arena-ready riffs on Kiss classics like “Strutter,” “Got to Choose,” “C’mon and Love Me,” “Rock and Roll All Nite” and countless others were the sonic fuel that helped transport four struggling New York City musicians into superstardom and, decades later, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Throughout Kiss’s storied career, both on record and in concert, lead guitarists Ace Frehley, Vinnie Vincent, Mark St. John, Bruce Kulick and Tommy Thayer have done the heavy lifting as fleet-fingered six-string soloists. But on the rare occasion when Stanley steps up to peel off a guitar solo, it’s always special, memorable and instantly hummable.

Neither a flashy soloist nor a speed merchant, Stanley makes each note count. He’s a distinctive stylist plucked from the George Harrison school of guitar playing, who hunkers down and takes the time to meticulously craft picture-perfect guitar solos that tell a story within a song.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When Stanley chooses to lay down a solo, whether it’s the exquisite Kossoff-flavored slow-hand finery on “Hold Me, Touch Me,” the searing metallic attack on “I Stole Your Love” or the epic David Gilmour–esque sonic flights of atmospheric fancy on “A World Without Heroes,” it’s always melodically inventive and in service to the song.

For much of the band’s ’70s heyday, his arsenal of axes leaned heavily on Gibson guitars, including the L6-S Midnight Special, Flying V, Firebird, Explorer and EDS-1275 double-neck. That all changed in the late ’70s with the introduction of Stanley’s first signature guitar, the Ibanez PS10, which became his go-to six-string.

Through the decades, his onstage rigs included models from a wide range of brands, including Hamer, B.C. Rich, Steinberger and, of course, Gibson. Stanley later aligned with Washburn and Silvertone on the creation of new signature models, but he is now back in the fold with Ibanez and involved in the development and design of his own line.

Now, as Kiss end their live career, Stanley graciously sat down with Guitar Player for a talk about his guitar journey — how it all began, and the sights and sounds from along the way. Sit back and enjoy his most in-depth and comprehensive conversation about all things guitar.

What’s your earliest memory of seeing a guitar?

Probably Eddie Cochran or Elvis. And with that you get Carl Perkins and everyone else from that era who fits the model — the guitar player as a frontman. But I’d go with Eddie Cochran and Elvis.

What made you want to play guitar?

The guitar was the messenger of rock and roll — the primary instrument. Certainly, you’ve got Little Richard with a piano, but the guitar was always the instrument of rock and roll. People think about the guitar solos and lead playing, but it was really the strumming — that was the call to arms. That’s usually what you heard first.

What was your first guitar, and how did you come to own it?

I bugged my parents, and for my 13th birthday I figured that I’d finally got them to get me an electric guitar. And as it turned out, they got me a really crappy used nylon-string guitar. I was heartbroken, because nobody that I had seen on American Bandstand or in [rock and roll concert promoter] Alan Freed’s shows, or rock and roll movies, like The Girl Can’t Help It — nobody was playing an acoustic nylon-string guitar. So I looked at it and put it under the bed and didn’t pull it out for quite a while.

But as I would eventually learn, to play guitar with some sort of depth and understanding, you really should start out playing an acoustic guitar. I think that an acoustic guitar is so much less forgiving, and it also requires nuances that the electric guitar doesn’t — or it does so in a different way. So at the end of the day, I think I was fortunate that I started out with an acoustic guitar.

How long did you play acoustic before you got your first electric?

Probably a year or so, if not more. My parents, God love them, they thought love meant denying your kids certain things, to toughen them up. So my first electric guitar I bought myself, and it was a two-pickup and pretty much a three-quarter-sized Vox copy of a Strat. It was a salmon color that Fender also used, one of their classic DuPont-type colors.

Where did you buy that guitar?

Back then, 48th Street was the holy land for guitars and amps. I used to do an almost weekly pilgrimage down there. I’d take a bus and a subway down to maybe 50th Street and then walk over there and go into all the guitar stores. It was very different then. Now you go in and they want you to play the instruments, much like bookstores.

If you went into a bookstore back then and pulled out a book, they’d say, “You’re going to buy that?” and it was very much the same with musical instruments. They were basically behind glass, and if you wanted to try something, you had to show them the money. Their first question was, “Are you buying today?” And if you said yes, they’d say, “Let me see the money.”

So I wound up buying my first guitar on 48th Street, but not at Manny’s. Manny’s was like the premier instrument store, with drums, guitars and woodwinds — everything. I would just go down there and drool and wait for rock stars to come in so I could see the people I’d seen on television.

I saw Hilton Valentine, who was the guitar player from the Animals. I also saw Leslie West. Leslie, God love him — he looked like Jimi Hendrix if Jimi Hendrix weighed 400 pounds. So it was exciting for me, and I made it a weekly trip.

What gear did you have circa 1967–’68?

I could only afford one guitar at a time, so at that point I had an SG Les Paul that cost me $120 at a pawn shop right near Tompkins Square Park in New York City. There used to be a pawn shop there, and my mom had hawked a diamond ring, which was wonderful, and got me a Fender Twin Reverb. I had no pedals or anything like that.

The people who I was most enamored with and the bands that I saw at the Fillmore East were plugged into amplifiers. Hendrix had pedals, as did some other guitar players, but for the most part your sound came from a great guitar and usually a Marshall amp, and if you couldn’t get that sound, you needed a new amp or a new guitar.

Prior to that, I had a Hagstrom 12-string electric guitar, because I couldn’t afford a Rickenbacker and I was very into the Byrds, and for that you needed a 12-string. Then I got rid of that and got the SG Les Paul. And from there, for quite a while, I would trade out a guitar to get a different one.

My next guitar after the SG Les Paul was a Gibson double-cut Les Paul, which was $200. Guitars were not out of reach at that point. Dan Armstrong on 48th Street had all these classic vintage guitars and a wall full of mid-’50s to ’59 and ’60 Les Pauls: gold tops, sunbursts.

The expensive ones could be $700, $800, which to me was a fortune. But compared to what they wound up being valued at now, they were attainable. Guitars were not investments at that point. People weren’t buying them like art or stocks.

What was your practice regimen? Were you picking up songbooks and learning from those, and slowing down records to learn and master parts?

Early on, I realized that I didn’t want to be the flashy lead player. As much as I admired them and wanted much to be like them, I became much more involved with being a rhythm guitarist. Very often, rhythm guitar was looked at as what you do before you can play lead. And there were certainly consummate guitar players who, yes, they could play lead guitar, but that wasn’t their wheelhouse, really.

Whether it was Keith Richards or Pete Townshend — or even David Crosby or one of the greatest right hands ever, Richie Havens — that was more fascinating to me: not what the left hand was doing, but what the right hand was doing.

When my son, Evan, started playing guitar — and by the way, he’s just a smoking great guitar player — in the beginning I said to him, “Right now it’s all about your right hand. It’s all about your wrist. It’s all about your palm. It’s all about those subtleties.” And that, I think, is a great foundation to start with.

How far you want to go after that is really up to you. I mean, Jimmy Page is just a killer rhythm player who happens to also be a spectacular lead player and arranger. But his rhythm playing is as good as anybody’s, and better than most.

What was the first holy grail guitar that you bought?

Well, I started collecting guitars in the mid-’70s, when I could finally afford to have more than one guitar. And I found myself wanting to acquire a prime example of what were the top guitars. At that point, the word went out and people started bringing guitars to our shows, and when we would pull in there’d be people standing out back with guitar cases. So it made it really fun.

The first guitar I bought that was of that stature was a ’58 sunburst Les Paul with cream humbuckers, and I paid $2,200 for it, which was a fortune. I wound up with nine guitars that were really outstanding examples of each specific model, and the start of it was the ’58 sunburst.

Let’s talk about some of the guitars you used early on with Kiss.

Early on I played a Gibson Les Paul ’54 reissue that came out in the ’70s. The first really good guitar I had was a 1960 Gibson SG Les Paul, which is when they were making the transition from Les Paul guitars to what later became SG guitars.

I also had a custom-made guitar, a half Flying V. It was made by a guy in the Village named Charlie LoBue [who also made Gene Simmons’ basses early on]. It was stolen at our first New York gig, with [first-wave punk artist] Wayne County.

Then one of my favorite guitars, a Gibson Firebird, got wrecked. This guy, Corky Stasiak, who was the assistant engineer on Destroyer, knocked it over in the studio and broke the neck off. It couldn’t be repaired.

So Gibson made me a copy of it. Ultimately, I lent the copy to somebody, and they sold it. [laughs]

Were you using some of these vintage guitars in the studio, onstage or both?

I would use them in the studio. I would never take them on tour, for a couple of reasons. The look of the band has always been so specific that the idea of being up there with a sunburst Les Paul wasn’t character consistent. So ultimately I wound up designing the Ibanez PS10, which really was based upon all my favorite Gibson guitars.

The specs came off a bunch of guitars that I loved, and the construction was based on a mahogany body with a maple cap, and a mahogany neck, so it was very familiar. And if you play one, it feels very familiar, because the specifics — as far as the measurements and construction and all the hardware go — are classic. They’re tried and true.

A glam-rock hero inspired the creation of your cracked mirror Ibanez Iceman guitar.

Yes, that’s right. My mirror Iceman guitar was actually not a unique or original idea. Noddy Holder from Slade had a top hat with these huge circular mirrors on it. So when they hit Noddy’s top hat with the lights, these beams seemed to come out of his head. It was such a cool idea, and that’s where the idea for the mirrored guitar came from. In many ways, Slade was the English counterpart to us. They wrote these great anthems. Live, they were simple, but, boy, did they put their boot up your ass!

Humble Pie were one of your primary influences for the sound of Kiss.

Yes, they most certainly were one of the inspirations behind Kiss’s sound. Steve Marriott was a terrific rhythm player. Seeing them perform at the Fillmore and watching Steve Marriott command and preach to an audience was something that inspired me, and his approach was something that I wanted to do onstage, but in my own way.

In terms of your chord choices, positions and inversions, who were you channeling?

In the early days of Humble Pie, Steve Marriott and Peter Frampton created a sound like one big guitar. That was a part of the template for what I wanted to do. I’ve always wanted Kiss to be like one big guitar, which means that the other guitarist and I play different inversions. The goal was to do something that one guitar couldn’t, but play it in a way so that it becomes like one big guitar.

My first exposure to the blues was Albert, Freddie and B.B. King and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. I really appreciated what they were doing, but I was more intrigued with where things went from there.

Still, I think to do your best as a musician, you need to be exposed to a variety of music that’s outside of what you innately do. That’s why there are Kiss songs where I can point out the Spinners; there are Kiss songs where I can point out the Four Tops, Free — all kinds of groups.

I grew up listening to opera and show tunes and R&B, and I went to bluegrass hootenannys and over to the Village and saw Dave Van Ronk at the Gaslight Cafe. For me, it was all about funneling everything that I was exposed to and loved into something else.

With Keith Richards, when I heard things like “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” or “Brown Sugar,” I didn’t realize that he was playing in open G, so a lot of my playing was about using sus chords and trying to get that feel. It wasn’t until, gosh, the ’70s that I realized I could take my low E string off and tune to an open G. So a lot of my playing was rhythm-based.

My songs and a lot of the riffs I came up with were based on my limitations, which sometimes can be your biggest asset. I might start a lick and not know where to go and just throw in something basic. That’s what I did with [1976’s Destroyer cut] “God of Thunder.” I had the beginning of the riff and I didn’t know where to go, so I bent those chords after the riff.

With “I Want You” [from 1976’s Rock and Roll Over], I had the riff and I didn’t know where to go halfway through it, so I did a bunch of hammer-ons on the G string. So I was inspired by a lot of people and took what I could within the scope of what I could do, or wanted to do.

With songs like “Flaming Youth,” “Shout It Out Loud”, “Comin’ Home” and countless others, I hear a lot of Pete Townshend in your playing and approach.

Well, if an orchestra played the same figures the same way time and time again, it would get repetitious. But it’s how you build on a theme, and that theme can be chordal; it can be a riff. But to me, the best themes don’t stay stagnant; they evolve as the song evolves.

Back to Zeppelin, Jimmy is Beethoven. Jimmy uses textures and layers, different kinds of guitars, and builds parts and elaborates on themes. I’ve said to him, “The first time I saw Zeppelin, I was 17, and it raised the bar for me to a level that I felt I can’t achieve. But it’s important to know that that level exists.”

Jimmy Page reigns supreme as your guitar god.

I was aware of the lineage and the history of the role of the hot-shot guitar hero in the Yardbirds, starting with Eric Clapton who left to join John Mayall’s Blues Breakers and was replaced by Jeff Beck, who at one point was joined by his friend Jimmy Page.

Although I didn’t see that lineup, I saw the Yardbirds in New York after Beck had left and Jimmy was playing lead. When I saw the Yardbirds live, I was blown away by his ability to play what had already been done and still give it his own interpretation. For me, in many ways, he was the future.

What was interesting about the guitar players in the Yardbirds is how they all had a love for the blues and took it in different directions, particularly when you listen to Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, who seemed less purist and more adventurous. It’s interesting to note that both the Jeff Beck Group, which Beck formed after his stint in the Yardbirds, and Led Zeppelin virtually came about at the same time.

Led Zeppelin’s first show as Led Zeppelin was October of 1968, and they were rehearsing before that. The Jeff Beck album Truth came out in late July of ’68, so both in a sense were incubating at the same time.

It’s interesting how Jimmy Page’s vision of what was possible was so much broader and wider. He understood the complexities and subtleties of producing and arranging and brought that to his band.

As brilliant as Jeff Beck was, that’s something he couldn’t do, whether it was the limitations of the people he played with, which he himself has said he found frustrating, or just the fact that Jimmy Page consistently turned out to be a visionary. Beck had to use his phenomenal guitar talents to compensate for a lack of interesting or original material.

Ace loved Jimmy Page. He very much had a Page sensibility to his playing. The idea of having another guitar player, at least to me, was to play the stuff I couldn’t. I had no problems holding down the fort in terms of chords and rhythms, but somebody had to blow the roof off with a wailing solo, and Ace really had the goods.

As much as Ace loved Clapton, Beck and Hendrix, and he really did, there’s so much Page and so much swagger in his early playing. It’s so clear and so obvious that some of Ace’s signature licks are very much inspired by Jimmy Page. There’s a lot in “100,000 Years” [from Kiss’s self-titled 1974 debut]. There’s loads of things there that are, at least for my money, quintessential Page.

Let’s talk about your guitar interplay with Ace. What made that chemistry work for such a long time as a complementary partnership?

Ace was a very good rhythm player and really played methodical solos. His solos made sense. They weren’t noodling. They were thematic, and as a rhythm guitar player he was solid and could play more than your basic first position. So it helped to create what I wanted to do, which was have that sound of one big guitar. And as I said, that has always meant two people playing different inversions and playing tight enough that it’s something that neither one could do on their own. Ace and I played well together. We really did.

In the studio when you’re working up songs, was there a lot of discussion between you and Ace coming up with complementary parts for each to play?

Thankfully, there wasn’t a lot of that. We didn’t have to work at it. It was intuitive, and we were both capable of playing rhythm, and that gave us the flexibility and the ability to pretty instinctively play different inversions of chords and do things that at least to our ears were sonically pleasing.

What was the process in terms of layering guitars? Would you change up guitars if you were doubling a rhythm track yourself? Would you try an SG and then bring in a Les Paul, or would you pretty much stick with the same guitar?

Depends on what we were doing. At one point, we would record a guitar part, and then we would vari-speed the tape ever so slightly when we doubled it so that between the two guitars there was much more of a shimmer as opposed to just doubling it. That’s something Bob Ezrin taught us. For the most part, a “double” meant doubling my part, not changing and using another guitar.

I think that, at least for this kind of music, you can overthink it. It’s not unlike when we were in the studio at one point with one producer and he brought in all these amps and said, “Well, this sounds like a Marshall and does this, this and this, and this amp sounds like a Fender.” And I said, [laughing] “Well, if it sounds like a Marshall, then let’s just get a Marshall.”

All the bands and all the people that I loved and saw and inspired me, they were basically playing a Gibson guitar plugged into a Marshall amp. And if you got a Gibson guitar and a Marshall amp and it didn’t sound good, you either needed a new Gibson guitar or a new Marshall amp. It was just that simple.

Even in the last decade, there have been times where guitar players and other bands have said, “Your guitar tone is so great. What are you using?” And it’s a guitar and an amp and all those other things that people use to try to replicate that vintage sound. I think they’re on the wrong track. It’s in your hands and it’s in your guitar and amp.

With respect to your lead playing, I definitely hear a lot of Paul Kossoff, with that great slow vibrato. When I was speaking with Bob Ezrin about your guitar solos, he described them as vocal melodies that are beautifully constructed.

Bob is right. I tend to think melodically and vocally when I play a solo. It’s not enough to me to play scales. I’d rather memorize a solo based upon a melody as opposed to a scale.

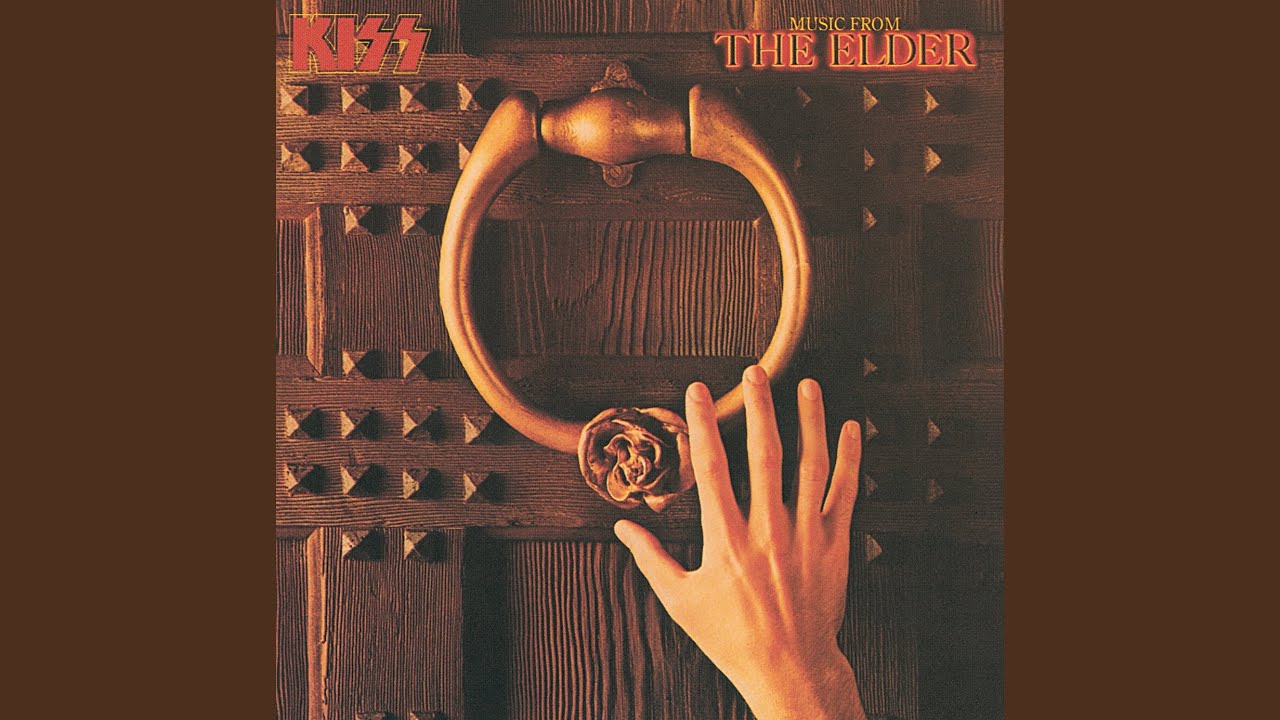

Your solo on “A World Without Heroes” from (Music From) The Elder may be your shining moment as a lead player. Did you experiment in the studio to come up with that, or was it prepared beforehand as a written solo?

I just created it while in the studio. It had an emotional feel to the song, and all I was doing was connecting to that. A solo has got to be so much more than playing in the right key. It’s about the expressiveness and the emotion. I think that comes more from a solo that somebody can sing. That’s going to have more emotion in it than somebody doing acrobatics. I may be impressed by the acrobatics, but it does nothing for me emotionally.

I’m not that kind of player, and I’m not interested in others who do that. I certainly respect and appreciate people who can play with dazzling speed and cram more notes into a measure than the average player, but it does nothing for me. It’s an exercise in futility. It’s nothing more than gibberish.

With Ace, and then later with Vinnie Vincent, Mark St. John, Bruce Kulick and Tommy Thayer, how much input would you have into their solos?

I have to say that when Ace was great, he was great, and he came up with so many memorable parts and solos. I can’t remember anything that he was told to do, except the run up in “Love Gun,” which is from a Blues Magoos song called “(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet.” Deep Purple nicked that same run.

But other than that, Ace really came up with some very identifiable and really stellar guitar solos, not because they were incredibly intricate but because they made a lot of sense and some of it was counterpoint to what we were playing rhythmically. He did some very interesting things.

So when it came to working with Ace, I don’t remember ever suggesting anything to him. He took the reins and galloped on. I can say that there are solos later on after Ace was gone, that, if I didn’t play them, I sang them to the guitarist and they learned it. I will say that many of the solos and pieces on Creatures of the Night certainly sound familiar to me. I mean, just because I can’t play something doesn’t mean I can’t sing it, right?

Gear Tour

T.J. Silljer, Paul’s End of the Road guitar tech, fills us in on the Starchild’s stage arsenal for Kiss’s final shows.

When it comes down to it, all it takes for Paul Stanley to get his game on is a guitar plugged straight into an amp. ”We have tried different things in the rig, as far as modular effects or overdrives,” explains T.J. Silljer, Stanley’s guitar tech on the End of the Road tour.

“But at the end of the day, we usually just plug directly into the amp and Paul ends up saying, ‘Nothing sounds better than a great guitar plugged straight into a great amp.’ We only use one channel on the amp for the whole show.

“If he wants a little less gain, he uses his volume knob to clean it up a bit. That’s one of my favorite things about Paul: I love how old school he is with regard to guitar.”

MAIN GUITARS: Ibanez PS10 (Black, Gold, Cracked Mirror, Rhinestone) Gibson Custom Shop “Custom” V Modified by Billy Rowe Ibanez PS60 (used as breakers) According to Siljer, “Each V was customized to suit Paul’s specifications. Body contour, neck profile, frets, hardware, finish and pickups were all changed to make a unique Paul Stanley version of a Gibson classic.

“Paul doesn’t want to play the same thing everyone else is playing, so he prototyped his own version of the V, making changes to the neck, hardware, body, finish, frets, pickups and adding a custom tailpiece. He wanted a great-playing and great-feeling guitar, but also wanted a unique piece of art you can’t find anywhere else.”

PICKUPS: Ibanez PS10 Seymour Duncan SH-1N ‘59 Seymour Duncan SH-14 Custom 5 Gibson V Seymour Duncan SH-1N ‘59 Silljer Pickups True Heritage P.A.F.

STRINGS: PS10 Ernie Ball Custom Gauge 13–52 Gibson V Ernie Ball Beefy Slinky 11–54 PICKS Dunlop celluloid .73

GUITAR TUNINGS: D standard on all guitars

AMP & CABINET: ENGL Paul Stanley signature model Marshall 1960B Cabinet

“Paul knows exactly the sound he is looking for,” Silljer explains. “When playing the PS10 guitars, we have the Duncan Custom 5 in the bridge. That pickup is straight rock and roll tone, and his custom ENGL amp was built around this guitar and pickup.

“With this guitar-and-amp combination, we usually run everything at 12 o’clock and make small adjustments from there. For the Gibson V, we run a slightly lower-output PAF-style pickup I wound, and I bump up the gain to match output for the front of house.”

STRAPS: Custom leather beaded strap by Carlino Guitars

MICS: Shure SM58

For more information, visit paulstanleyguitars.com