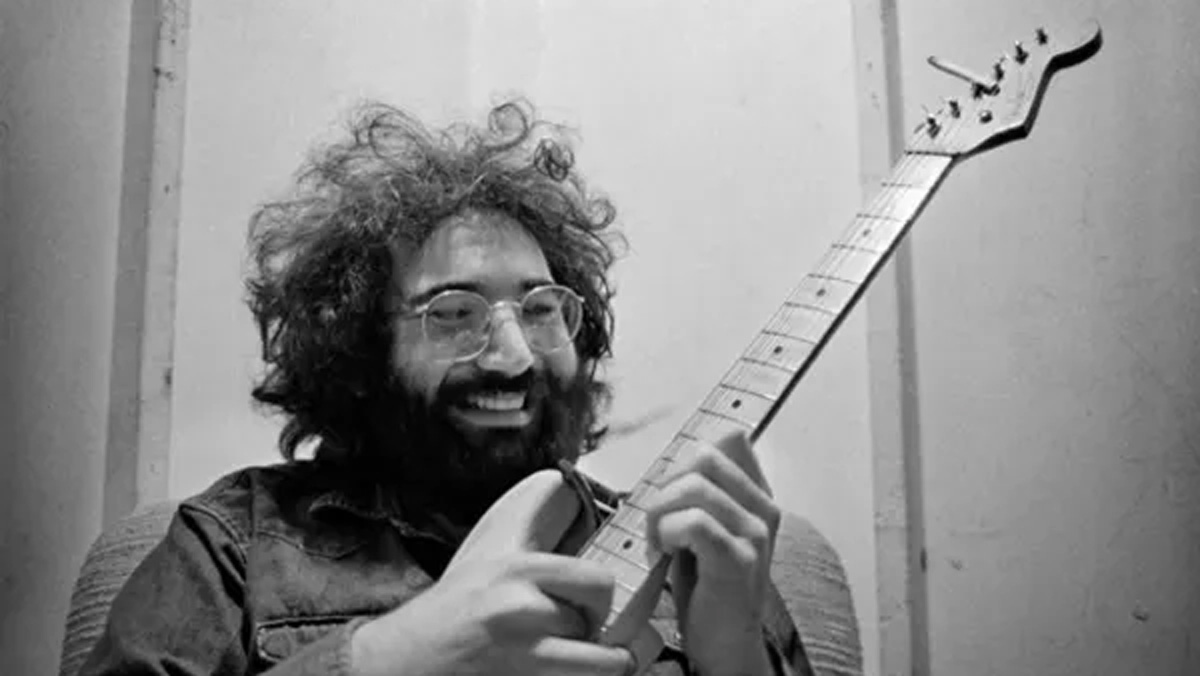

How Jerry Garcia Revolutionized the Custom Guitar Industry

He died on this day in 1995. But one of Jerry Garcia's many achievements was how he revolutionized the custom guitar industry...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ask any guitarist for a short list of players who dramatically changed the way the electric guitar is made and played, and inevitably names like Les Paul, Jimi Hendrix, and Eddie Van Halen will be mentioned. But one player who only occasionally gets similar credit, even though he certainly belongs among the list’s top five, is Jerry Garcia.

From his pivotal role in helping to establish the custom guitar industry to his very early adoption of rack systems for amplification and effects, Garcia pushed modern electric guitar technology and innovation forward in ways that few other players have since, thanks to his passion for creative freedom onstage and in the studio.

During the late Sixties and Seventies, a cottage industry grew in the San Francisco Bay Area to support the Grateful Dead’s discriminating demands for sophisticated instruments and state-of-the-art sound systems. Many of the people that the band worked with early on formed companies that are still going strong today, including Alembic, Furman Sound, and Meyer Sound.

In the Dead’s early days, Garcia played mass-produced guitar models by Fender, Gibson, Guild, and Martin, but from the early Seventies onward, he generally preferred instruments made by individual luthiers, like Doug Irwin and Stephen Cripe, or fledgling, visionary local companies, like Travis Bean.

Raised in a musical family — his father was a professional musician who played reed instruments in swing bands, and his mother played piano and listened to opera — Garcia started taking piano lessons early in his youth. In 1947, when he was only five years old, his father died in a fishing accident, and shortly afterward Garcia moved in with his grandparents, who introduced him to country music.

Sometime in the late Forties, he heard Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs’ Mercury recordings and decided to learn to play bluegrass banjo. Even though he had lost the tip of his right hand middle finger in an accident when he was only four, Garcia managed to master the intricate right-hand fingerpicking technique required for playing bluegrass banjo, using his thumb, forefinger, and ring finger.

“For me, the banjo is kind of the gateway to music,” Garcia told Relix magazine. “That’s how I found my way into music. I liked the sound of the music that was made with a five-string banjo — the incredible clarity and the sparkling brilliance of it. I was attracted by the intensity of the Mercury [Flatt & Scruggs] album with ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ and ‘Pike County Breakdown.’ I couldn’t believe the sound of it. It was startling.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In 1953, when Garcia was 11, he moved back in with his mother and new stepfather. During this time, his older brother Clifford introduced him to rock and roll and blues music, and the two sang doo-wop harmonies together. Garcia soon found the sound of the electric guitar irresistible, but he didn’t start playing the instrument until a few months after his 15th birthday, in 1957. Having received an accordion from his mother as a gift, he eventually convinced her to trade it for a Danelectro guitar and a small amp.

“I learned by ear, mostly from records,” Garcia told Jon Sievert in a 1978 Guitar Player magazine interview. “I listened to Freddie King and B.B. King extensively. That was my first exposure, mostly because the Bay Area didn’t have that many guitar players back when I started playing.”

During the early Sixties, Garcia played in a variety of musical settings that foreshadowed the stylistic diversity of the music he later played with the Grateful Dead. He performed as a solo artist, accompanied by a 12-string acoustic guitar, and in 1962 he started playing banjo and guitar with a variety of old-time string and bluegrass bands. One of those bands, Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, also included keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and guitarist Bob Weir as members. After discovering the Beatles, Garcia, McKernan, and Weir decided to change musical direction, abandoning bluegrass and performing rock and roll in a new band they formed in 1965 called the Warlocks. Eventually, they changed their name to the Grateful Dead.

With the Warlocks, Garcia played a stock circa-1964/’65 cherry-red Guild Starfire III with a thinline single-cutaway body, a pair of Guild humbucking pickups, and a Bigsby B-6 vibrato. This remained his main guitar for the next two years, and he used it to record the Grateful Dead’s eponymous debut album. He played the Guild through a Fender Twin Reverb combo while with the Warlocks, but by 1967 he had expanded his rig with the addition of a Fender Showman head and a Fender 2x15 speaker cabinet.

After the release of The Grateful Dead, Garcia began to acquire and play a variety of different Gibson solidbodies for the next three years. At first he played a black 1957 Gibson Les Paul Custom with P-90 single-coil pickups and a Bigsby vibrato, but he soon switched to a mid-Fifties Les Paul “Goldtop” fitted with a Tune-o-matic bridge and a nonstandard trapeze tailpiece.

During the summer of 1968, Garcia was seen onstage with another late-Fifties Les Paul Custom, but this one had a standard stop tailpiece instead of a Bigsby. These P-90–equipped Les Pauls were likely the guitars that he used in the studio to record the Dead’s Anthem of the Sun and Aoxomoxoa albums. As the venues that the Grateful Dead performed in became larger and larger, so did Jerry’s rig, which by this point in his career consisted of three Fender Twin Reverb amps driving two 4x12 cabinets loaded with JBL D120 speakers.

By late 1968, Garcia switched allegiance to humbucker-equipped Gibson SG Standard models. His first SG was a Bigsby-equipped 1967 model that he purchased new. Garcia used this SG, which also featured a round American flag sticker and large “double” pickguard, for the concerts recorded for the Grateful Dead’s first live album, Live/Dead, as well as for the group’s performance at Woodstock Festival on August 16, 1969. In 1970, he acquired an early Sixties Gibson Les Paul Standard with an SG-style body, which had its original “sideways” vibrato unit replaced by a stop tailpiece.

Garcia also started playing Fender guitars around this time. A performance filmed at New York City’s Fillmore East on February 14, 1970, shows him with a sunburst 1963 Fender Stratocaster. During the summer of that year, when the Grateful Dead and Delaney & Bonnie were on tour together in Canada, Delaney Bramlett loaned Garcia a rosewood Telecaster previously owned by George Harrison. However, the most famous Fender associated with Garcia is a hybrid Strat with a 1957 maple neck and a 1963 ash body that Graham Nash gave to him in 1971. Nicknamed Alligator for the cartoon alligator sticker that Garcia affixed to its pickguard, this Strat marked the beginning of Garcia’s radical departure from the mostly stock, off-the-shelf guitars he had used previously.

Increasingly dissatisfied with the limited tonal palette of most production guitars, Garcia sought a single instrument that could provide him with a wide variety of tones and textures at will, allowing him to obtain any sound he pleased during the band’s extended jams. Unlike most guitarists, who simply changed guitars between songs when they needed different sounds (and justified their habit of acquiring an ever-growing collection of instruments), Garcia preferred to use the same guitar for an entire set, changing instruments only when necessary, if a string broke or a technical problem arose.

The first attempt to satisfy Garcia’s wishes was a guitar made by Rick Turner of Alembic, which at the time provided the Dead with sound reinforcement, recording, and instrument support. During the late Sixties, Turner built a guitar featuring a neck from an early Sixties Gibson Les Paul/SG Custom, his own mahogany and walnut body design (similar to that of Turner’s later Model 1 guitar, sans cutaway), three pickups, and custom two-channel/stereo wiring. Garcia played Turner’s guitar for only a few months before switching to Alligator, but from that point onward, his preference for customized guitars never faded away.

Garcia frequently handed Alligator over to Turner and Alembic’s Frank Fuller to perform various modifications on it between March 1971 and August 1973. The most obvious mods were the installation of a brass bridge, tailpiece, and control panel, but the most innovative feature was the Alembic Strat-o-Blaster preamp, which boosted gain and also prevented signal loss when using long cables on large stages.

In 1972, Garcia bought another custom guitar, one built by Doug Irwin. A guitar designer and builder, Irwin had, in 1970, joined Alembic, where he was trained by Fuller and Turner, but he was working on his own when Garcia approached him. The guitar Garcia purchased from him was called Eagle, and it was the first guitar that Irwin made entirely by himself for Alembic. It featured a laminated bird’s-eye maple and amaranth (a.k.a. purpleheart) body, brass hardware, and Bartolini Hi-A pickups. Garcia purchased the guitar for $850 and was so impressed with Irwin’s work that he immediately asked him to build another guitar to his custom specifications.

This was the beginning of Garcia’s long and productive relationship with the builder. Irwin completed Garcia’s first custom-order guitar in May 1973, selling it to him for an astounding (at that time) $1,500. After receiving the guitar, Garcia gave his first Irwin guitar to his guitar tech, Ram Rod, who sold it in a Bonhams auction in 2007 for $186,000. The new custom featured a neck-though-body design made of maple and amaranth, but unlike Garcia’s previous Irwin guitar it had a slimmer profile and asymmetrical shape that provided better balance.

Irwin installed an Alembic Strat-o-Blaster preamp and three Strat pickups in the guitar with traditional Strat wiring, but knowing that Garcia would likely experiment with different pickups and electronics, he wisely mounted the pickups on a removable plate and routed a completely hollow pickup cavity. Irwin even provided Garcia with a second plate, ready to go, with humbuckers installed on it.

Garcia instantly fell in love with the guitar — nicknamed Wolf, for the cartoon wolf sticker that he affixed below the bridge — and it became his main instrument. A few years after he received Wolf, the guitar suffered a couple of falls during a European tour and was returned to Irwin for repair. While it was in his shop, Irwin replicated the wolf sticker with wood inlays and replaced the headstock overlay with one featuring his eagle logo.

In 1977, at Garcia’s request, Irwin installed an innovative buffered effect loop in Wolf. “It allows me to have all my effects pedals wired to the guitar and bypass them all with a switch,” Garcia told Jon Sievert. “I use a stereo cord, and the signal goes from the pickups to the tone controls and pickup switch. The signal then goes through the effects, back into a network box, and up the ‘B’ side of the stereo cord, back into the instrument before the volume pot, and then out to the amp. The effects always see the guitar as if it had full output voltage.”

As much as Garcia loved Wolf, he continued searching for other instruments. In 1976, while Wolf was being repaired, he discovered a new company making guitars in the San Francisco Bay Area: Travis Bean, named after its main luthier and founder. Garcia initially mocked the aluminum necks featured on Travis Bean’s guitars, but he was pleasantly surprised after trying one and eventually added two Travis Bean models — a TB1000A with humbuckers and a TB500 with single-coil pickups — to his arsenal. Garcia performed with these guitars often during the late Seventies and even had the TB500 modified with the same buffered effect loop installed in Wolf as well as a unity-gain buffer made by John Cutler.

Beginning in the mid Seventies, Garcia experimented in a similar fashion with amplification and effects. During the early Seventies, he was using a rack-mounted setup consisting of a preamp section from a Fender Twin Reverb amp and McIntosh power amps, starting with MC3500 models, which were later supplanted by MC2300 amps. He replaced the Fender Twin with a Mesa/Boogie Mark I in 1975, although he went back to using Twins onstage in the late Seventies. Garcia’s effects setup evolved dramatically as well, starting with just a Vox wah at the beginning of the decade but quickly growing to consist of an MXR Analog Delay, MXR Distortion Plus, MXR Phase 100, Mu-Tron III envelope follower, Mu-Tron Octave Divider, and Mu-Tron Vol-Wah.

Garcia continued to modify Wolf after he got the guitar back from Irwin in 1977. In 1978, he installed DiMarzio Dual Sound humbuckers in the bridge and middle positions and a DiMarzio SDS-1 single-coil at the neck. Irwin also installed coil-tap switches for each humbucker. Garcia played Wolf until July 1979, when Irwin finally completed a guitar that Garcia had ordered in 1973 at the same time that he had picked up Wolf. This guitar was known as Tiger, after the image of a tiger inlaid in the oval preamp cover, below the bridge.

When Garcia ordered Tiger, he gave Irwin complete freedom to make the best guitar he could. The result was a true work of art, with a body constructed from dazzling, contrasting layers of cocobolo, maple, and vermillion, and featuring brass binding and a floral pearl inlay on the back. The neck is western maple with a padauk center strip, its ebony fretboard featuring exquisitely detailed pearl inlays. Irwin’s electronics were as innovative as his craftsmanship was stunning. Pickups initially consisted of DiMarzio Dual Sound humbuckers at the bridge and middle (replaced by DiMarzio Super IIs in 1982) and a DiMarzio SDS-1 at the neck, with coil-tap switches for the humbuckers, a five-position pickup selector, a master volume control, neck/bridge and middle pickup tone controls, a unity-gain buffer, and a mini toggle switch for the effect loop.

Finally, Garcia had a guitar that was capable of producing the various sounds he needed onstage from one instrument. “I’m the kind of player who generally plays one guitar at a time so I can learn its idiosyncracies,” Garcia told Sievert in an interview conducted before Tiger was completed. “I really seek a kind of universal guitar, something that will sound like anything I want it to at any given moment.”

With Tiger, he had at long last achieved that goal. “There are 12 discrete possible voices that are all pretty different,” he said. “That gives me a lot of vocabulary of basically different tones.” Tiger remained Garcia’s main guitar for the next 11 years — the longest any of his guitars enjoyed that status for a continuous run.

In 1990, Irwin completed Rosebud, which Garcia considered the guitar builder’s masterpiece. Rosebud was similar to Tiger, but it featured three humbucking pickups, a Roland GK-2 hexaphonic guitar synthesizer pickup with its MIDI and synth controls internally mounted, and hollow body cavities that reduced the overall weight by two pounds. Garcia started using guitar synths in the late Eighties, installing a Roland hexaphonic pickup on Wolf, which he brought out of retirement and used mainly for the extended free-improvisational jam section of the Dead’s concerts, known as “Space.” With Rosebud and the Roland guitar synth, he finally had a single instrument that provided him a full assortment of guitar tones and other sounds, like brass and woodwind instruments, vocal samples, percussion, violins, mandolins, and special effects.

As much as Garcia loved his Doug Irwin guitars, he was absolutely blown away when aspiring luthier Stephen Cripe presented him with a custom-made replica of Tiger called Lightning Bolt, so named for the trademark Grateful Dead design inlaid on the cover plate below the bridge. Garcia called it “the guitar I’ve been waiting for,” and it immediately succeeded Rosebud as his main guitar after Garcia had San Francisco luthier Gary Brawer replace the electronics and install a Roland guitar synth pickup and controller in it. Garcia ordered a backup from Cripe, who made a second guitar called Top Hat, named for the graphic design on the control cover, which depicted a skull wearing a stars-and-stripes top hat. Delivered in April 1995, the guitar was in Garcia’s possession just over three months before he died, so it never enjoyed significant playing time with him.

A few other electric guitars briefly passed through Garcia’s hands during his career, including a late-Fifties Gibson Les Paul Special, an early Seventies Les Paul Deluxe, and an Ibanez Musician MC-500, which was inspired by Alembic’s designs. He also frequently played acoustic guitar both with the Dead and in various side projects that included the Jerry Garcia Band, Old and in the Way, and several collaborations with mandolin virtuoso David Grisman. In the studio he preferred to play Martin D-18 and D-28 dreadnoughts, while onstage he performed with Takamine acoustic-electrics during the early Eighties and, later, various custom Alvarez-Yairi GY1, GY2, DY98, and DY99 acoustic-electric models that he helped design.

On July 9, 1995, at Soldier Field in Chicago, Illinois, Garcia performed his last concert with the Grateful Dead. Because Lighting Bolt was in the shop for repairs, Garcia played Rosebud instead. However, about halfway through the set the guitar began to experience technical problems, so Garcia finished the show with his old friend Tiger, which he had brought along as a spare. It was an unexpected but fitting twist of fate that Garcia played his last notes onstage with the guitar that was his trustworthy companion longer than any other instrument he had owned.

But perhaps the most fascinating ironic twist is that the very last guitar that Garcia may have ever played was not one of his iconic custom electric creations but rather an uncharacteristic — for Garcia — vintage archtop acoustic 1939 Gibson Super 400N that he used to record “Blue Yodel #9.”

This performance, recorded in the studio with his good friend David Grisman on July 16, 1995, was Garcia’s last recording session before he checked into a drug rehabilitation facility a few days later. About four weeks afterward, Garcia passed away after suffering a heart attack, on August 9, 1995.