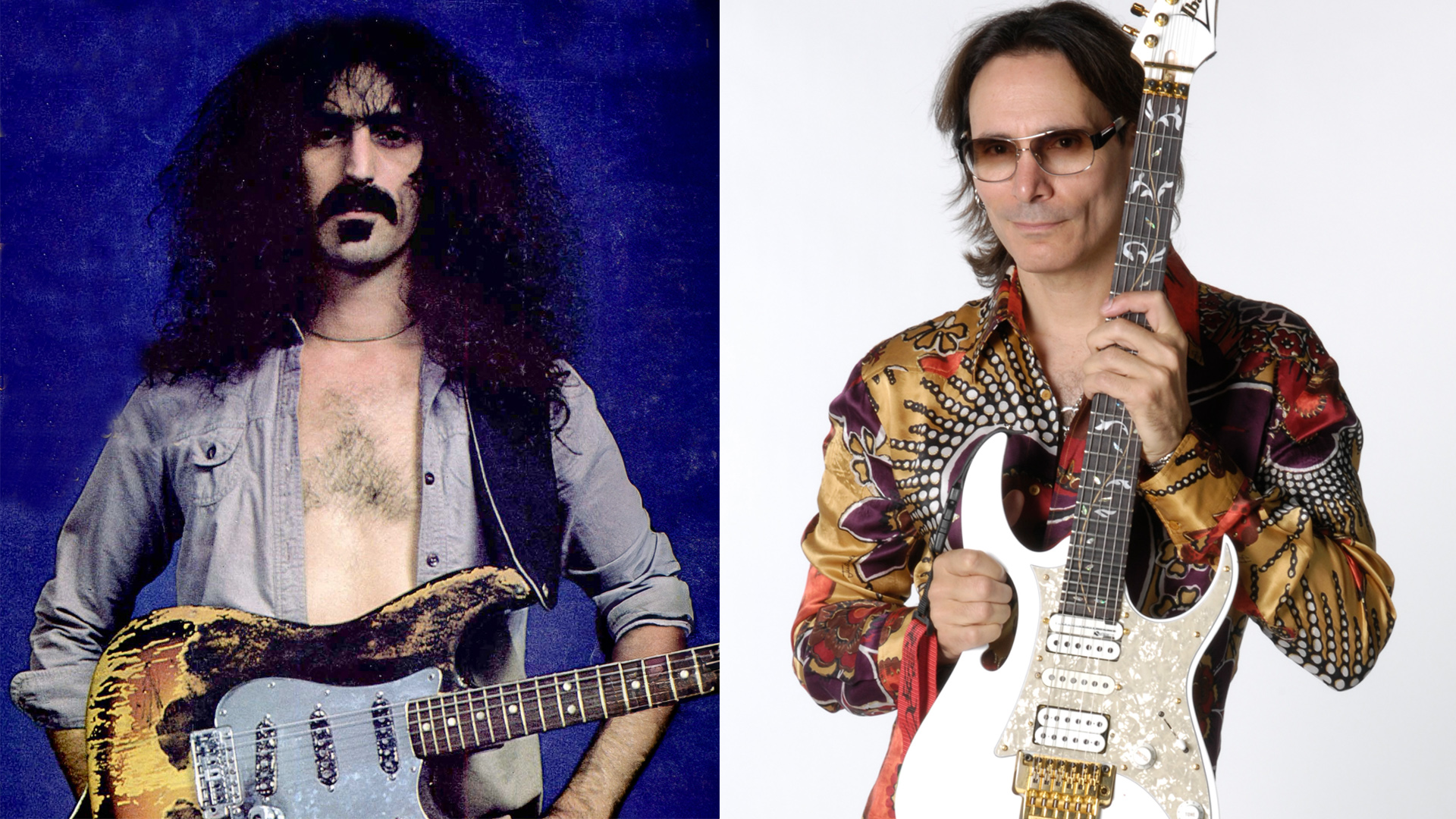

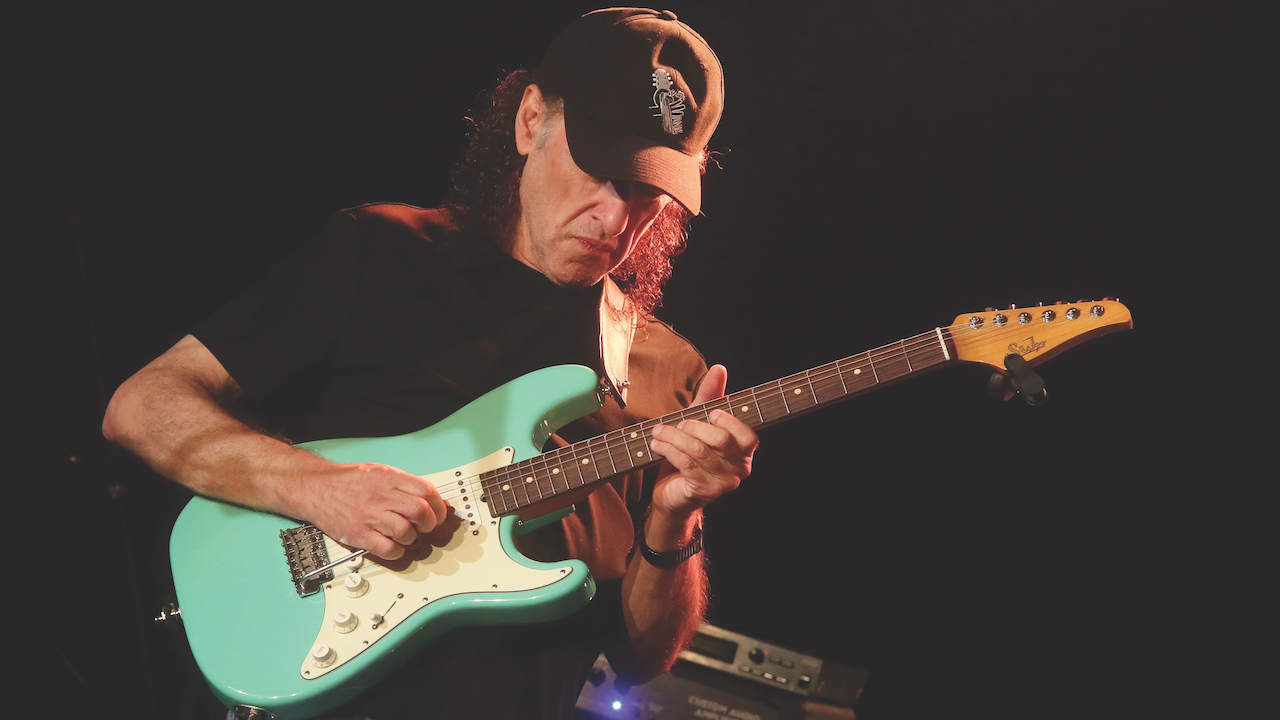

“I try to avoid using my middle pickup. That’s the Stevie Ray Vaughan sound. My treble pickup sounds more like me”: Scott Henderson on trombone-emulating pedals, and balancing dense arrangements with blues progressions

Scott Henderson spent lockdown training his ears and building improv skills. As his new album, Karnevel!, shows, his jazz chops reached new heights, but his blues-rock roots remain as strong as ever

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Growing up as a die-hard blues-rocker in 1970s South Florida, Scott Henderson fell in love with the sounds of that era’s big-name rock guitarists.

“Ritchie Blackmore, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck… I grew up listening to all those guys,” Henderson tells Guitar Player. “I mean, your influences stick with you, man. I learned how to play by ear from listening to cats like that, and I don’t think you ever lose those roots.”

A decade later, Henderson would make a name for himself, not as a blues-rocker, but as one of the prominent fusion guitarists of the ’80s and ’90s, carrying on in the tradition of his mentors Jean-Luc Ponty, Chick Corea, and Joe Zawinul, all of whom he had toured and recorded with. And while Henderson may have made significant contributions to Ponty’s 1985 album, Fables, 1986’s The Chick Corea Electric Band, and the Zawinul Syndicate’s 1988 outing, The Immigrants, it was in the context of Tribal Tech, the hard-hitting funk-fusion band he formed in 1984 with bassist Gary Willis, that his creative juices really flowed and his scintillating virtuosity truly flourished.

Henderson’s searing blues-rock roots would eventually bubble up on a series of side projects, including 1994’s Dog Party, 1997’s Tore Down House, and 2002’s Well to the Bone. But otherwise, he seldom strayed from his love of jazz and fusion, collaborating with bassist Victor Wooten and drummer Steve Smith on two volumes of Vital Tech Tones fusion recordings and with bassist Jeff Berlin and Dennis Chambers on 2012’s HBC, which included revved-up power-trio renditions of Zawinul’s D Flat Waltz, Wayne Shorter’s Mysterious Traveller, Billy Cobham’s Stratus, and Herbie Hancock’s Actual Proof.

More recently, the guitarist joined with the phenomenal Parisian rhythm tandem of electric bassist Romain Labaye and drummer Archibald Ligonniere to record 2019’s People Mover. Now the trio has reprised its tight chemistry on the newly released Karnevel!, which finds Henderson at the height of his six-string powers. As he tells Guitar Player, the new songs developed from improvisation and ear-training skills that he developed during the lengthy COVID lockdown.

“I have a lot of harmony in my head, but I don’t always have access to it in real time,” Henderson says. “Like, I’ll play something, but it’s not what I heard in my head. So I did a lot of solo guitar playing during the COVID break, just all by myself in my room. I guess what it really was is the practice of ear training. Like, if I hear it, where is it on the neck? Where is that chord I’m looking for?”

The result is that Karnevel! is an album of sophisticated, jazz-inspired harmony, with elaborate arrangements. But as suggested by its cover shot of a boy flashing the devil horns while riding a guitar-themed merry-go-round, Henderson hasn’t completely abandoned his youthful influences. Karnevel! also finds him indulging in some of the blues-rock playing that informed his early years, making the album a compelling mix of the styles that have defined this virtuoso’s 40-year career.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Karnevel! manages to combine very intricately arranged jazz cuts with surprisingly straightforward blues tracks. For example, there’s no denying the sheer directness and stinging intensity of something like the shuffle blues number Haunted Ballroom.

“Yeah, I’m trying to keep that element of the blues in the music, because I love blues. And I thought, ‘I haven’t done a I-IV-V blues progression since [1994’s] Dog Party,’ so it was fun to get into the blues again and just play something like that. But, of course, that sense of harmony kicks in a little in the second half of the tune, where it becomes like a mixture of blues and jazz, but essentially it’s a plain old, good old blues shuffle, which everybody loves. I never get tired of the chord progression.

“But these days, anytime you do a I-IV-V, everybody says, ‘Oh, that’s Stevie Ray Vaughan!’ Well, I love Stevie Ray, but I wasn’t really that influenced by him, because by the time he came out I had already been inspired by the same guys who influenced him, namely Albert King and Jimi Hendrix. So one of the things I try to avoid is using my middle pickup, because that’s the Stevie Ray sound.

“I usually use my treble pickup because it sounds more like me. But as far as direct influences on me, Albert King was definitely a huge one. I think Albert King is an influence on everybody who plays guitar.”

John Scofield often talks about the profound influence Albert had on him.

“Yeah. And I’ve been influenced by John Scofield too. Sco is probably one of the first guitar players I ever heard as a kid who was playing jazz with more of a rock tone. The first time I ever heard Sco was on that [1976] Billy Cobham/George Duke album, Live on Tour in Europe, and I had never heard a guitarist play jazz lines with that kind of a rock-blues tone before. That really influenced me and got me more into jazz.

“Coming more from the rock and roll side, I was never into the hollowbody, clean-tone thing as much as distortion guitar. So when I heard Sco do that, I thought, So you can play those notes on electric guitar with distortion! It was a revelation to me. And that’s kind of what I do these days. It’s more of a bebop mode in that I’m more like a horn player.”

On Covid Vaccination you replicate a whole horn section on multiple guitars. I’m guessing the title is a tongue-in-cheek reference to Tower of Power’s Soul Vaccination.

“Yeah. That was kind of hard to do, because I had to find pedals that emulated the horns. So for the trumpet sound I used one of my distortion pedals but with a wah-wah half-open, so it had that nasal sound, like a trumpet. For the saxes it’s more of a fizzy-raspy sound, so fuzz tones worked really good for that.

I love the kind of pedals that give you unexpected shit. It’s a lot of fun

“And I found a couple of different fuzz tones – one for the alto sax, one for the tenor sax – and then for the bari sax I tuned the low E string on my guitar way down and used a different fuzz tone for that. And for the trombone, I’ve got this really cool pedal called a Trombetta Robotone, which actually does make a guitar sound like a trombone. It’s got that kind of fluttery thing that happens when the trombone is played really low.

“It was really a labor of love to do this track because I have just been blessed by Tower of Power. I love those guys and I’ve really enjoyed their music over the years, so it was fun to do a tribute to them.”

Can you run down the different guitars you played on this project?

“Most of the main parts are played with my Suhr Strats with ML Standard pickups, but I added the Jerry Jones electric sitar on Karnevel! and Carnies’ Time. On Covid Vaccination I used a Les Paul in the middle pickup position for the rhythm guitar parts, because that’s the tone Bruce Conte used in Tower of Power. I also used a Danelectro ’59 resonator guitar, which is basically an electric dobro, on Bilge Rat and Carnies’ Time. On Acacia I played acoustic guitar on the intro and on the ending.”

On Bilge Rat you’re playing slide guitar. You have a particularly nasty distortion sound on that track. Is that a Moogerfooger [MF-102 Ring Modulator], which you’ve used in the past?

“No, that's a combination of a Fulltone Octavia and the Zvex Fuzz Factory. I think the first part of the solo starts out with the Octavia, and then later on in the solo I kick on the Fuzz Factory. It goes into warp drive and starts making some pretty weird sounds. And on Sky Coaster, the solo sound is a Spaceman Effects Sputnik III pedal. It’s a really cool fuzz because it has an extra button that changes the circuitry and it just goes wild, so you never know what to expect.

“You play a little bit, you hit that button and it freaks out. And that kind of inspires you to play what you’re going to play next, because you never know what the thing’s gonna do. It’s totally random. I love those kind of pedals that give you unexpected shit. It’s a lot of fun.”

The new record is bookended by two pieces, Karnevel! and Carnie’s Time, where you’re playing what sounds like my Electro-Harmonix Ravish Sitar pedal.

“It’s a Jerry Jones electric sitar, the same guitar that Denny Dias played on Steely Dan’s [1972 hit single] Do It Again. I used it on my 2015 album, Vibe Station, too, where I did a guitar-drum duet with Alan Hertz on the song Manic Carpet. I plugged it direct into my Fender Bassman amp and it sounded really good. The funny thing is, it’s a cheap guitar – only $600. And it sounds great, but it’s a bitch to tune. I probably spent more time tuning it than playing it on this new album.”

Tell me about your tune Acacia.

“That’s the name of a street in Florida that I used to hang out on. It’s actually by a cemetery. I used to walk there at night. But I thought it would be cool to have some acoustic guitar on the record, and when I was playing solo guitar one day, those chords just came out. I came up with the melody later. But I thought it was a nice way to showcase Romain. He’s such a nice chord player on the bass.

“He gets beautiful chords, which we also used on the tune Blood Moon from the People Mover record. It’s great to have that really beautiful, super-low chordal sound. And then he overdubbed fretless on the melody. That’s not one of the songs we play live, because that would be too hard to do. There’s too many parts, too many things going on.”

Your acoustic guitar arpeggiating on Acacia is so bright, it sounds like a harpsichord.

“It’s a combination of the acoustic guitars in stereo. The acoustic guitar has a piezo pickup under the bridge, but I also mic it with the Neumann 87. So I put the Neumann 87 on the left and the piezo pickup on the right, and it gives you this really nice stereo image of the acoustic guitar. And then I mixed in electric through a Korg Pandora PX5D multi-effects processor, which puts a sort of metallic shine behind everything. It’s a combination of sounds that worked nicely together.”

On a tune like Puerto Madero, you’re going back and forth between playing fingerstyle and using a pick. How did that technique develop?

“I realized when I started playing trio that I was going to have to play the melody and the chords at the same time onstage. So I got into this thing of playing the melody with my fingers on the top string with chords under it. I guess the difference between me and the hollowbody guys is there’s always a little bit of distortion in my chords, because it sort of evens them out; it gives them a little bit of compression. And I think hollowbody guitars have a natural compression.

“I hear a lot of jazz players, and, when they play, the chords seem very even. If you play a clean Stratocaster, it’s not so even; notes pop out. But if you play through a pedal and get just a little bit of distortion, it compresses it so that the chords are more realized. If you played a chord on a piano you’d hear pretty much every note, and that’s what I’m striving for on guitar.”

A lot of these songs were written in real time as opposed to the sort of hunt-and-peck process of elimination way of writing that I used to do. And there’s nothing wrong with it. We can’t all be Joe Zawinul and sit down for five minutes and compose Birdland

Given that, was Joe Pass an influence on you, or Lenny Breau?

“Not so much Joe Pass, but Lenny Breau for sure. And Wes Montgomery, too. I never really liked the sound of a pick scraping across the strings. That’s not my thing. Joe was more about scraping the pick across the strings, which is an old bebop sound. Bruce Foreman does that now really well, but that’s not really my style. My style is to hit all the strings together, like a piano player would. So I have to use my fingers.”

You mentioned that you wrote all the music for Karnevel! during the COVID pandemic.

“Yeah, I spent a lot of time during COVID just playing solo guitar. And I really wanted to improve my ability to realize harmony in real time, which is something I’ve never really been all that good at.

“So, as I got better at that – and I think I spent a year practicing just that – a lot of these songs were written in real time as opposed to the sort of hunt-and-peck, process of elimination way of writing that I used to do. And there’s nothing wrong with it. We can’t all be Joe Zawinul and sit down for five minutes and compose Birdland. But there was a lot less of that hunt-and-peck on this record. A lot of the tunes were written in real time, just me sitting there playing the guitar and coming up with the stuff.”

Is that where your solo guitar piece Greene Mansion came from?

“Yeah, it came from playing guitar by myself, just solo, with no pre-written things. And the guys that do it so well, like Keith Jarrett – he sits there at the piano and he doesn’t need a standard; he just starts playing and he goes where it goes. That’s something that I really admire about people like Scott Kinsey, where he can sit down and play with nothing written and take it to so many beautiful places. That was my goal during the pandemic. So a lot of these songs were written that way.”

And is that tune named for the great fingerstyle guitar master Ted Greene?

“Yes. That’s a good story. When I took some lessons with Ted many years ago, I was walking back to my car after one lesson, and when I looked back at his apartment building, it was one of those huge complexes that stretched out for four blocks, like a beehive. I couldn’t believe that such a master lived in such an anonymous place, and I felt like he should be living in a mansion on the top of a mountain. That’s where the name Greene Mansion came from. My solo guitar abilities are on a kindergarten level compared to him.”

Karnevel! has a couple of pointed references to Ritchie Blackmore on Sky Coaster and Bilge Rat. You’ve stated on many occasions that he was a hero of yours when you were growing up in Florida.

“Oh, yeah, for sure. No matter what kind of music you get into later in life, you still have those roots with you from the old days. And I’m glad I do, because I still love that music. In fact, we were listening to Led Zeppelin in the van today on the way to tonight’s gig, and it was so much fun.”

Meanwhile, in terms of the writing on Karnevel!, it seems you are combining the influences of Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter in a way that hasn’t been done before on the guitar.

“I mean, they’re definitely two of my biggest influences. Wayne was such a brilliant player and has influenced so many composers. He’s been my hero for as long as I can remember. And it’s kind of funny, because most guitar players’ heroes are other guitar players. My heroes are mostly sax players and keyboard players. Most of my favorite music doesn’t even have a guitar in it.”

It shows in the very intricate, very challenging compositions you wrote for this album.

“Well, sometimes I wonder if it’s a little too challenging. For some people, a lot of harmony can be too much. They hear it and they go, ‘What the hell’s going on?’ There’s so much happening harmonically and they’re not used to music that moves that fast through the changes. But once you listen to it, you acquire a taste for it.

“I remember the first time I heard Wayne Shorter’s [1985 album] Atlantis. I thought I liked it, but at the same time I was kind of confused because there was so much going on. But as I listened to it more, I grew to love it. Now it’s one of my favorite records ever, and I hear every single chord change in it as definitely having to be there. And now I’m hoping that when people hear my music, even guys that listen more to classic rock or whatever, they’ll hear the record and hopefully the harmony’s not so ridiculously bizarre that they can’t get used to it at some point and dig it.”

Good luck with that!

“[laughs] Well, you know what they say: ‘The more chords you write, the less money you make.’ So maybe I’m trying to go to the poorhouse on this one.”

- Scott Henderson's Karnevel! is available to stream and purchase now.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.