“We were just flabbergasted.” The secret sound that has David Bowie’s “‘Heroes’” surging on the charts following its ‘Stranger Things’ appearance

Producer Tony Visconti reveals how Robert Fripp’s guitar work made the 1977 song a timeless anthem

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

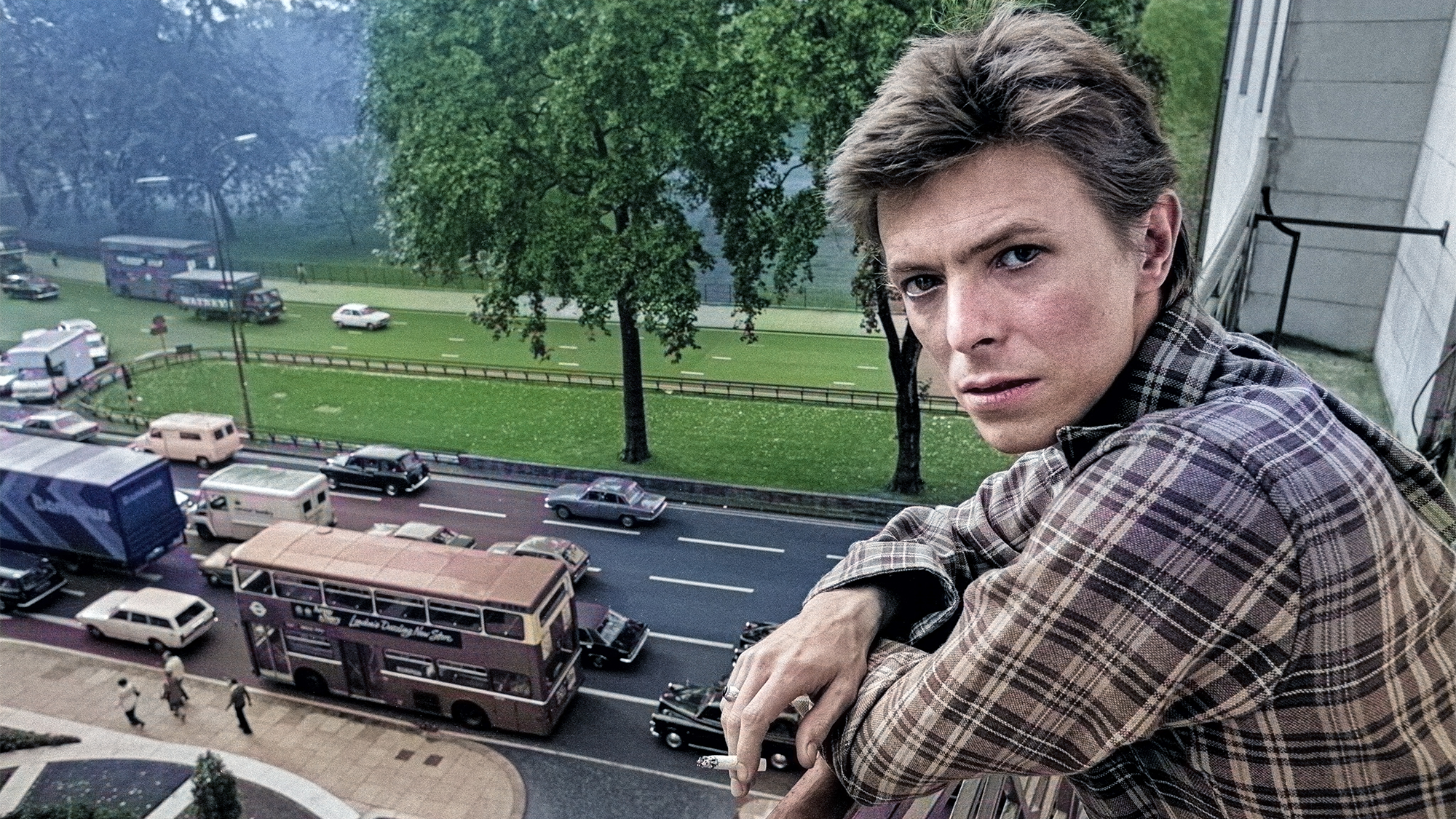

David Bowie’s iconic track “‘Heroes’” has enjoyed a resurgence since its appearance in the final episode of Stranger Things on December 31. Rolling Stone reports that, according to entertainment data company Luminate, the classic track has enjoyed a 500 percent bump on streaming services since it was heard over the show’s end credits.

The title track from Bowie’s 1977 album, “‘Heroes’” is an anthemic work built on a simple, repeating five-chord structure. While Bowie’s impassioned vocals are the song’s focus, much of its soaring power comes from the sustaining electric guitar tones created by Robert Fripp, then with King Crimson, who guested on the album as lead guitarist.

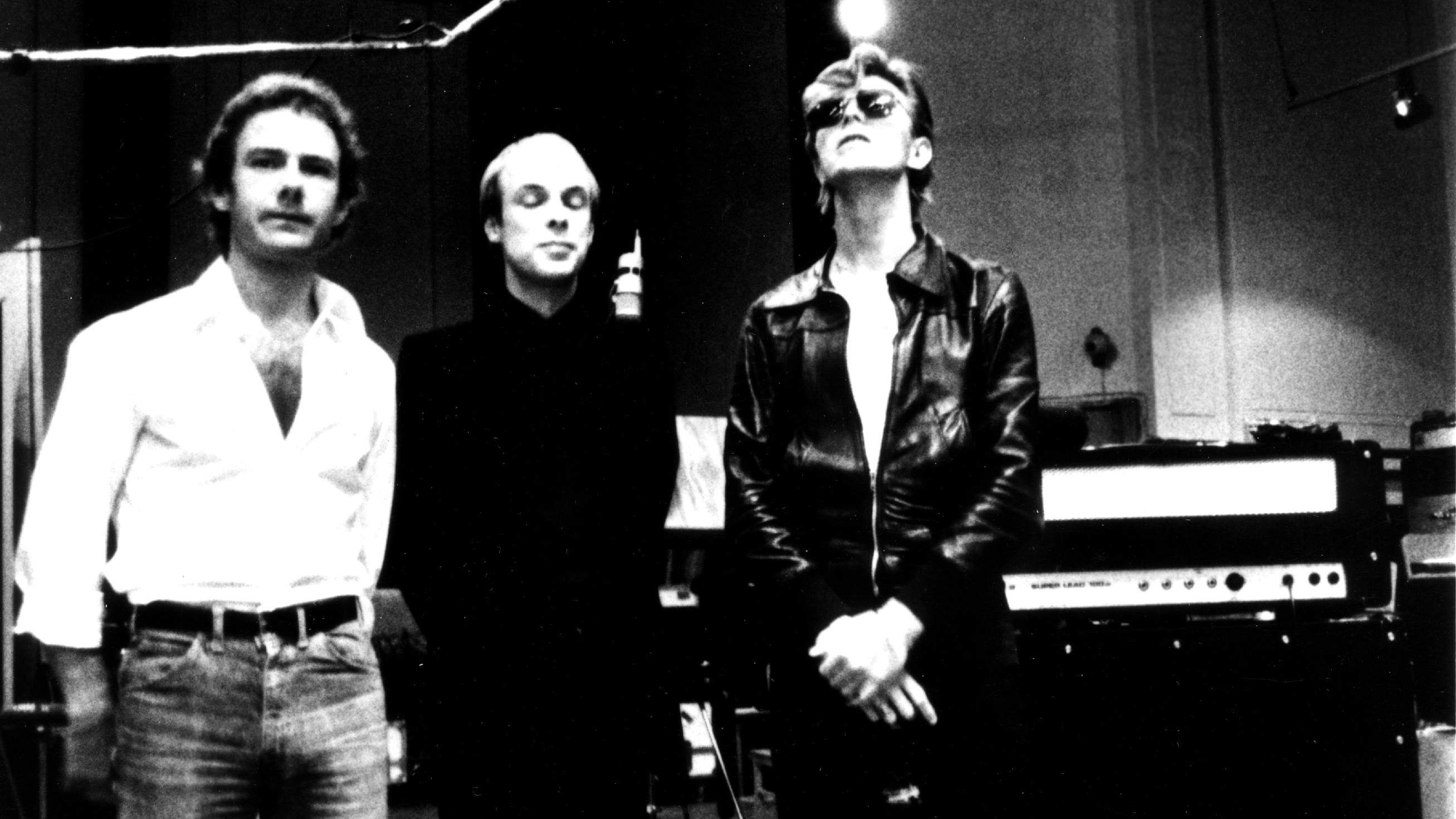

Like most of the album’s songs, “‘Heroes’” was composed on the spot in the studio, with Bowie and his collaborator, Brian Eno, working together to develop the material. It was Bowie and Eno’s second album together following Low, earlier that year.

Article continues belowProducer Tony Visconti says the backing track — consisting of Carlos Alomar on electric guitar, George Murray on bass, Dennis Davis on drums and Bowie on piano — sat for about a week before they returned to it. Eno added some synthesizer lines, and Bowie overdubbed brass and string sounds using a Chamberlin tape sample-playing keyboard and an ARP Solina, respectively.

It was Eno who suggested they have Fripp perform on the track. He and Fripp had previously worked together on a pair of albums — 1973’s (No Pussyfooting) and 1975’s Evening Star — on which the guitarist used Eno’s tape delay system with a feedback loop to create a droning wash of sustained and evolving guitar tones. Fripp would dub the system Frippertronics and go on to use it throughout the 1970s.

Fripp’s schedule left him just one weekend free. He came to Berlin carrying his electric guitar and no amplifier.

“He recorded his guitar in the studio,” Visconti said. “We had to play the track very very loud because he was relying on the feedback from the studio monitors. So it was deafening working with him.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While Fripp’s guitar has the droning sound associated with an EBow, Visconti explains that the guitarist was “playing” the feedback from the monitors.

“Fripp had a technique in those days where he measured the distance between the guitar and the speaker where each note would feed back,” the producer recalled in an article for Mixdown magazine.

“For instance, an A would feed back maybe at about four feet from the speaker, whereas a G would feed back maybe three and a half feet from it. He had a strip that they would place on the floor, and when he was playing the note F sharp he would stand on the strip’s F sharp point and F sharp would feed back better.

“He really worked this out to a fine science, and we were playing this at a terrific level in the studio, too.”

After Fripp recorded one track in this fashion, Visconti and Bowie felt it lacked something.

“And Fripp recorded a second time without hearing the first one,” Visconti explained. “It was a little bit more cohesive, but still quite wasn’t right, and he said, ‘Let me do it again. Just give me another track. I’ll do it again.’ And we silenced the first two tracks and he did a third pass, which was really great. He nailed it.

“And then I had the bright idea: I said, ‘Look let me just hear what it sounds like with the other two tracks. You never know.’

“We played it, all three tracks together, and you know, I must reiterate Fripp did not hear the other two tracks when he was doing the third one so he had no way of being in sync. But he was strangely in sync. And all his little out-of-tune wiggles suddenly worked with the other previously recorded guitars.

“It seemed to tune up. It got a quality that none of us anticipated. It was this dreamy, wailing quality, almost crying sound in the background. And we were just flabbergasted.”

Visconti dissects the song track by track in the video below.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.