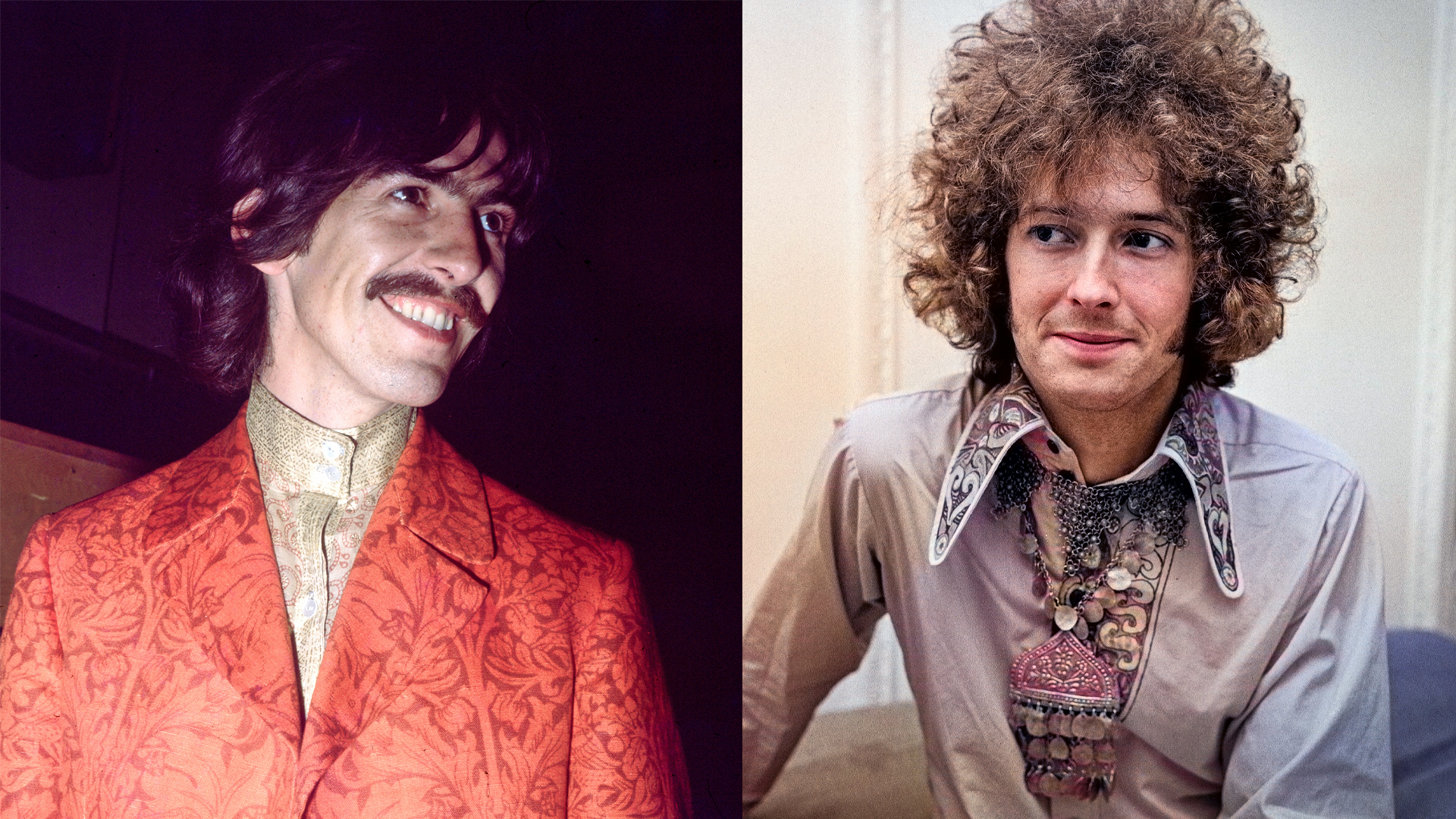

“I Only Play One Guitar”: Nile Rodgers Riffs On His Famed Hitmaker

As Fender releases a limited-edition replica, we talk to the man himself about the axe that defines his career.

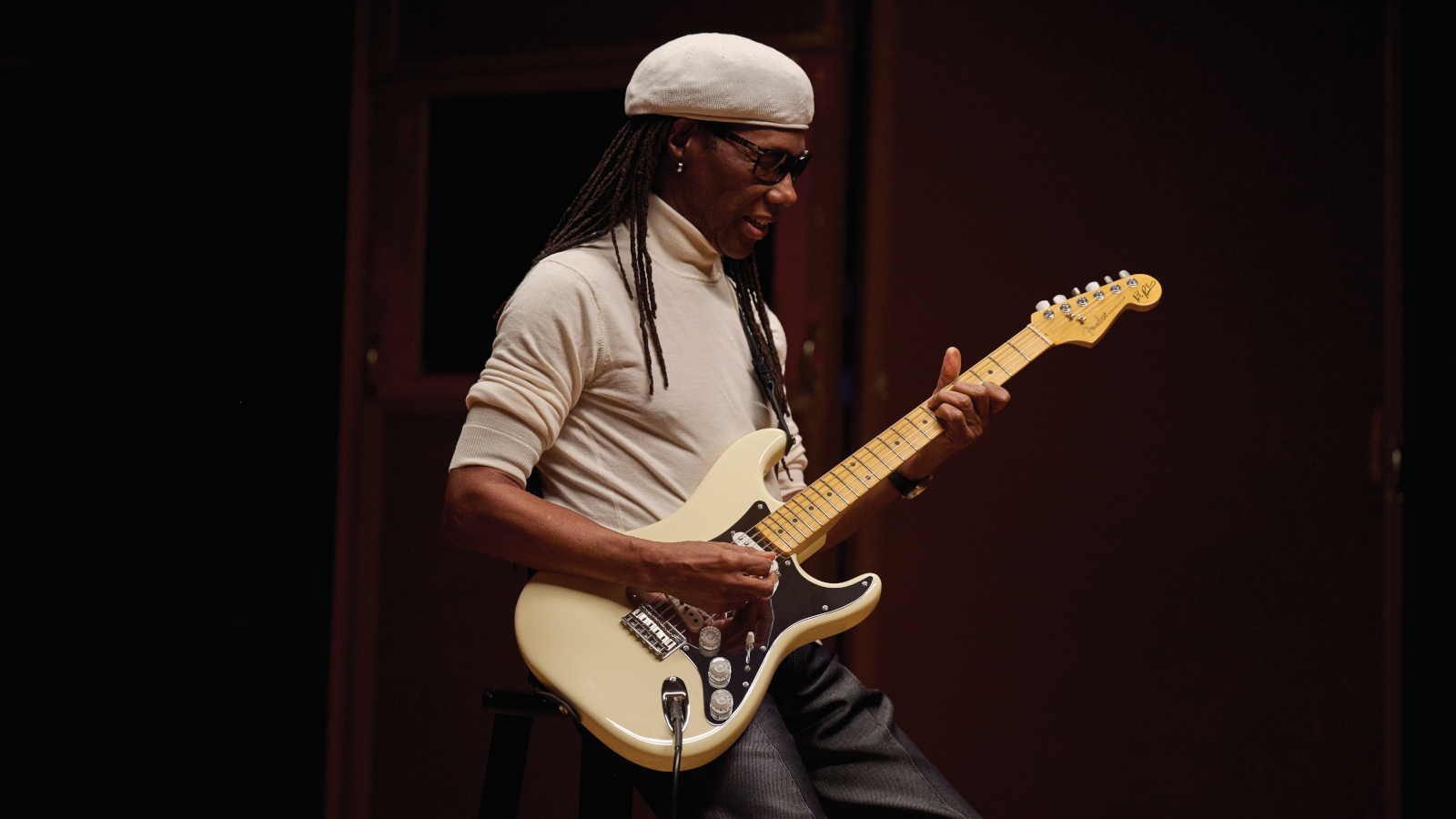

Besides being known for playing a white Stratocaster for his entire career with Chic, Nile Rodgers has used the same 1960 Fender on nearly all the albums he’s produced for artists such as David Bowie, INXS, Duran Duran, Diana Ross, Madonna, the Vaughan Brothers, B-52s, Mick Jagger, Steve Winwood and many others.

Now Fender has announced a limited-edition replica of the iconic instrument – the Nile Rodgers Hitmaker Stratocaster – which will feature such NR touches as the mirror pickguard, Gibson “speed” knobs and, or course, the smaller-than-standard body that remains one of the guitar’s mystifying elements.

“There are all these different stories I get from people at Fender, who are pretty knowledgeable, but you know, they weren’t there when that happened,” Rodgers says.

“The person who put that guitar together may have had any number of reasons for making it like that, but my guitar is smaller than a regular Strat.

My guitar is smaller than a regular Strat

Nile Rodgers

“A friend of mine, Richie Sambora, came up with a theory that it’s actually a Mary Kaye Strat [a style of Strat made in the 1950s featuring a blond finish/ash body and gold-plated hardware]. I was like, ‘Are you kidding me… Mary Kayes are like the most-prized Strats, and the guy screwed it up?’

“If it is a Mary Kaye, it would be funny because I also bastardized it. But it could have been the body mold for a Mary Kaye. Who knows?

“I know the neck is from 1959 because a person at Fender told me that one of the guitar-assembly people back then had written profanity on some necks – like every Strat has a person’s initials or some kind of identifier – and supposedly, as a disciplinary action, Leo Fender didn’t let them sign any ’59 Strats. So for a whole year the necks had no signature or “1959” inside.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“That may be the reason why as soon as they took my guitar apart they went, ‘Oh, it’s a ’59!’ But I didn’t know anything about that.”

You initially played an archtop, right?

Yes, I was initially playing a Gibson Barney Kessel. I had only played jazz guitars up until then. My mom bought me a Fender Mustang really early on, but a solidbody didn’t feel right to me, so I switched to a hollowbody.

I started out playing classical guitar almost exclusively, so I was accustomed to a big, fat body. When I started doing gigs playing electric, I just felt more comfortable with a big-box guitar.

What made you decide to switch to a Strat?

We were opening for the Jackson 5 on the American leg of their first world tour, and we were subbing for the O’Jays. The O’Jays and the Commodores were their legitimate openers, and I was in a group called New York City, and we would be a replacement for one of those groups whenever they got a gig paying more money or they were headlining.

I went to a pawnshop and I traded my Barney Kessel for the cheapest Strat in the store

Nile Rodgers

So we were down in Miami doing our own gig, and we had a group that was our opening act. They had a kid playing a Fender Strat, and they plugged into our equipment.

I was playing my Barney Kessel though Acoustic amplifiers, like Sly and the Family Stone used. My partner, Bernard Edwards [bassist, songwriter and co-founder of Chic], would always say to me, “You should play a Strat.”

Anyway, when this kid plugged into my amp and sounded, like, 10 times better than I did playing the same kind of songs, because we were basically a covers band, I was going, “Damn, that’s how the song should sound!”

So I went to a pawnshop and I traded my Barney Kessel for the cheapest Strat in the store. I didn’t know anything about them, but I just knew Bernard wanted me to play a Strat, and I loved Hendrix. So they gave me $300 for my Barney Kessel, and I got the Strat. But I didn’t like the color.

I worked as a guitar repairman back then, so I put the finish on it and did this sort of yellowish antique white to make it look like Hendrix’s guitar.

Also, I needed Gibson-type knobs, because there were a lot of R&B songs at the time that used the volume-rising technique, like the beginning of “Let’s Get it On.” [sings the part] And the way to do that is with the pinkie – unless you had a volume pedal, which I couldn’t afford.

I put the finish on it and did this sort of yellowish antique white to make it look like Hendrix’s guitar

Nile Rodgers

Being a guitar repairman, you must have been good at refinishing instruments.

Yeah, and I only used one coat of lacquer. And then I put the reflective pickguard on it, just ’cause it was a cool little thing to be onstage and be able to shine it in people’s faces in the audience. It was just some stupid idea I had, and it stuck.

And then, of course, I changed the machine heads so that the guitar would pretty much stay in tune. If you’ve ever seen me play live, I only play one guitar. I’d rather stop the show if I break a string. [laughs] In all of these years of gigging, I’ve broken maybe six strings.

When performing, you always have the switch in the forward position.

Correct. I’m always on the front pickup, although for recording I will use other pickup positions. That’s because, if you listen to my recordings, you’ll hear that so much of my stuff is doubled.

I’ll have two or three guitar parts, because I come from the era of R&B or pop records or what have you, and you had two or three guitar players on the record.

So I always have guitar arrangements, and I’ll change pickup positions. But I almost exclusively play with the neck position. You’ll rarely hear me go to the bridge pickup, ’cause my sound is already bright.

I have very light strings, and I play with a very light pick, and that’s because I want the sound to project, but I still want it to have body and roundness so the resonance will shine through on the lower notes. But with me it’s all about the first three strings and the middle three.

I have very light strings, and I play with a very light pick, and that’s because I want the sound to project

Nile Rodgers

Your tone is warm compared to the skinny sounds some funk players go for.

It’s warm, but it still projects. That’s something that developed from me recording with [engineer/producer] Bob Clearmountain and always having a direct signal as part of my sound.

Blending the amp with the cleanliness of the direct has become a thing, and I’ve gotten used to it, and my technique exploits that sound.

As a producer, you’ve always played guitar on the records you produce. Is it fair to say, whether it’s Bowie, INXS, the Vaughan Brothers or Madonna, we’re always hearing Nile Rodgers?

All of them. I would have to say as a producer, even when I’m producing a band, I play with the band.

If you go way back to the beginning of my production career, when I produced INXS, I played in the band. When I produced Duran Duran, I played in the band. When I did the Vaughan Brothers, I played in the band.

It’s just part of my style of production, because I like guitar hooks. So I always try and have a guitar part that makes a person want to play it, or if you take that guitar part out of the song, you feel like something is missing. But I don’t force myself on the band at all. That’s not what happens.

I always try and have a guitar part that makes a person want to play it

Nile Rodgers

Can you cite an example of how playing with the band helped turn a tune into a hit?

When we were doing “Original Sin” with INXS, for some reason they were having a difficult time playing the groove right in the pocket. I don’t know why. I felt like they were nervous for some reason.

So instead of just sitting in there at the desk, I decided to go out in the room and play with them. So that’s what I did, and what happened was, believe it to not, the drummer’s bass drum head broke after we did one take, and that take wound up being the record.

Visit Fender for more information.

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.