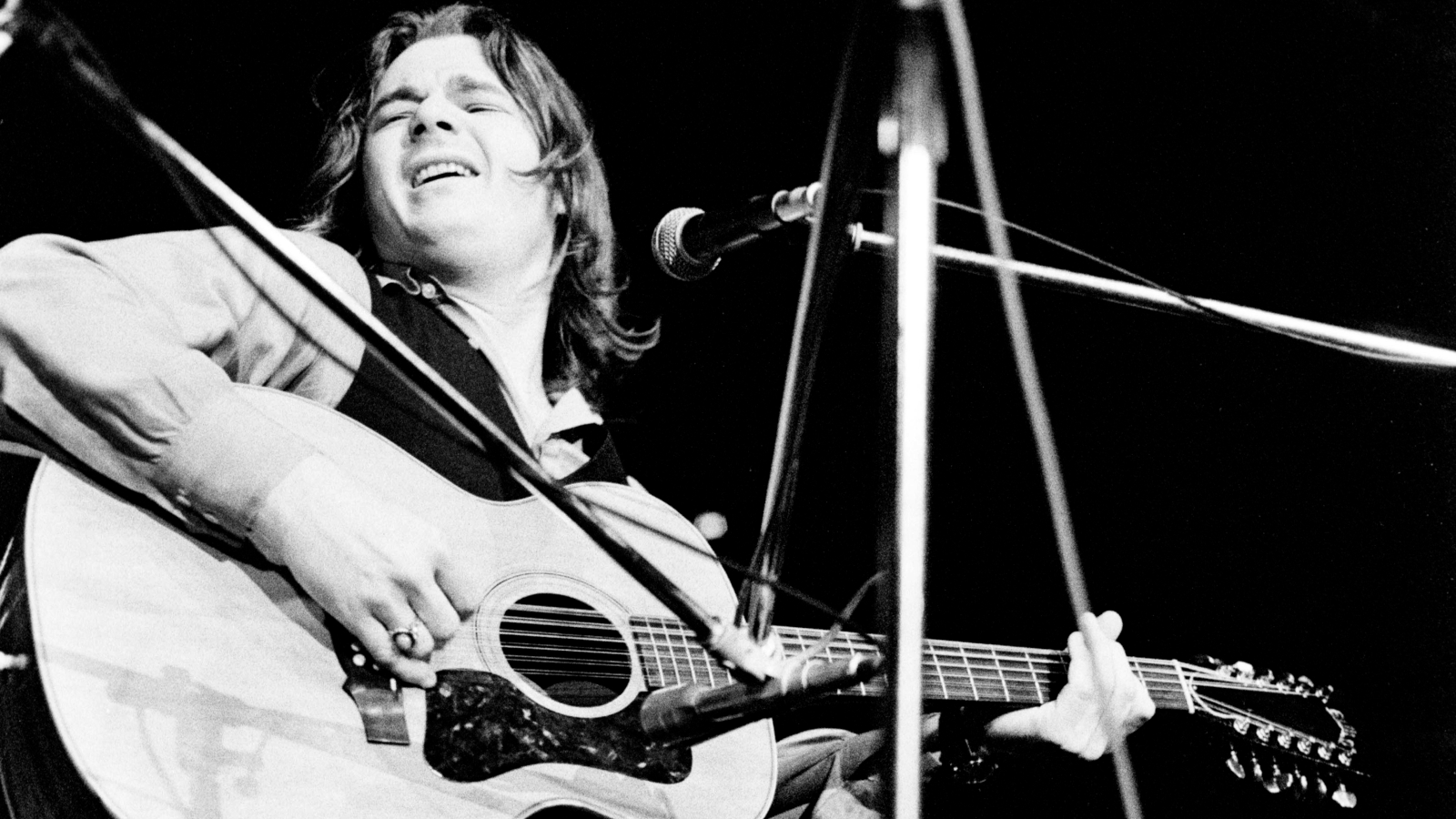

“The Song Was Literally Done in Two Hours”: Steve Miller Reveals How He Made His Unexpected 1973 Smash “The Joker”

Fifty years on, we take a look back at the chart-topping hit Steve Miller described as an “odd tune”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Being able to watch the great Les Paul work in his home studio and growing up in a family that enjoyed the company of top blues and jazz artists of the 1950s certainly gave Steve Miller a good start.

But it was his talents as a guitar player and songwriter, coupled with his sheer ambition, fearlessness and drive for perfection, that allowed him to evolve, in a relatively short amount of time, from a hard-hitting blues rocker to a performer of experimental music to a megastar whose parade of hits in the 1970s carried him on a tidal wave of popularity that the established forces in the radio and record industries simply couldn’t control.

A true force of nature, Steve Miller made music on his own terms, and his stories about how he did it are inspiring.

Here, he tells Guitar Player about the making of his Billboard chart-topping single “The Joker” from 1973’s The Joker album.

“The Joker” was a very different kind of song for you at the time. How did you develop it?

That was one of those songs where I wasn’t sure what I was writing. It was so different than anything else, and it wasn’t a song where you’d go, “Now there’s a hit single. Let’s put that on the radio.”

I didn’t know it was going to be a hit or think anything about it, but when I played it for the guys at Capitol, there was a kid at the playback meeting who said, “I kind of like that ‘Joker’ tune. I think it’s pretty cool.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It was really simple. I played it on a Guild 12-string acoustic tuned down to D, and I was playing it in the G position. It had this nice little ring to it, and it was a real lazy kind of tune.

When I finally got it all together, I was in L.A. and my band consisted of John King on drums, Dickie Thompson on keys and Gerald Johnson on bass. I had a very specific written bass line for Gerald that I wanted him to play, and when we cut the basic track it had a really great feel.

I didn’t know if it was something I really liked when I was working on it

Steve Miller

We recorded all the tracks for “The Joker’ at Capitol in two days, and then I sat around and did the overdubs.

Your guitar solo is instantly recognizable. How did you come up with it?

I was trying to figure out what I would do for a solo, and I had my Strat, which I’d set up for slide, and I ran it through a Leslie speaker. I think I had an overdrive pedal, and, of course, there’s wah on it for the wolf whistle.

The song was literally done in two hours. We cut the track, I did the overdubs, and it was finished. It’s an odd tune. I didn’t know if it was something I really liked when I was working on it. But there are a lot of things I really liked but didn’t put on my records.

It dominated the air for a year, and all of a sudden I had this huge hit single from a song that was really just a country blues kind of tune.

Catch the Steve Miller Band on tour this summer. Visit the website for information and tickets.

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.