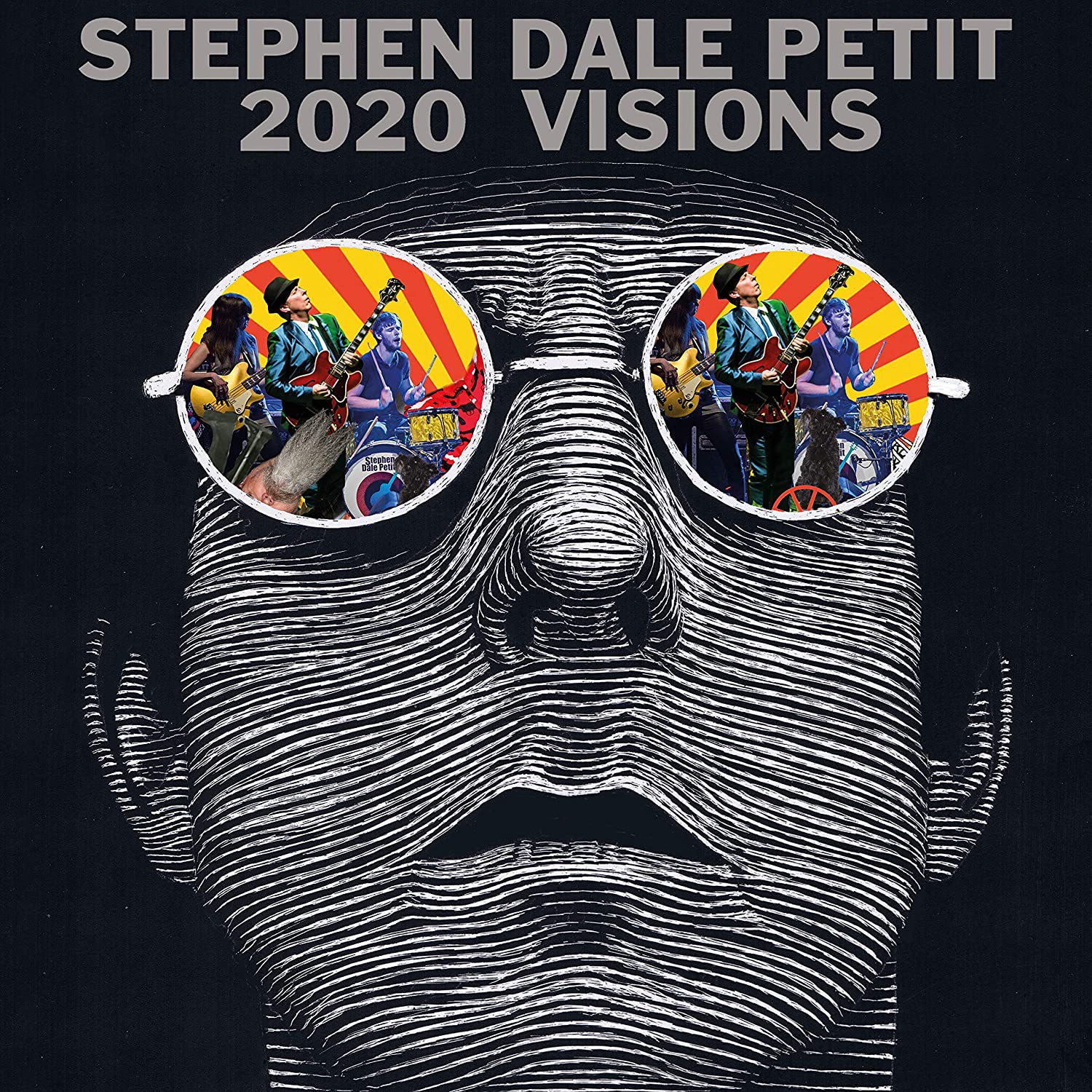

Listen to Stephen Dale Petit’s ‘2020 Visions’ – One of the Most Exciting Guitar Records We’ve Heard This Year

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On his sixth studio album, 2020 Visions, maverick guitarist Stephen Dale Petit has created a blues record unlike any other.

For one thing, it’s a concept record. For another, it presents a dystopian view of society, America in particular, with themes of factionalism, tribalism and alienation, all through the lens of someone gazing into the not-too-distant future.

In this case, that someone is an expat (Petit moved to England from California in the mid ’80s) who penned much of the material back in 2017 but is only now seeing his album – and a good many of his prescient predictions – become a reality.

“I guess it’s pre-dystopian, to make up my own term,” Petit says in a distinct British accent.

“Having not lived in America for so long, I’m kind of imagining what it must be like for a parent who arrives home after a trip. You walk into the house and the kids are going crazy, the rooms are all torn apart, and you go, ‘What have you done to the place?’ The son says, ‘She did it,’ and the daughter says, ‘He did it.’

“That’s my feeling about the polarization in America and how savage and how indoctrinated ideologically everything seems to be.”

Having not lived in America for so long, I’m kind of imagining what it must be like for a parent who arrives home after a trip

Stephen Dale Petit

Petit traveled to Nashville and cut 2020 Visions with producer Vance Powell back in 2017, and if various, unforeseen circumstances had not upended his plans, he would have released the album the following year.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

A cancer diagnosis – Stage 4, as it turned out – threw his world into a tailspin, and for much of 2018 he had to curtail most professional activities while dealing with treatment.

“It was a chemo and radiation regime every day for two months,” he says. “Brutal stuff. I’m all clear now, thank goodness, but it takes a while for you to get back up to speed.

“I did a couple of shows during that time, and it was strange, because I experienced this sort of artificial energy while performing, almost like a weird caffeine kick or something. But that drops off and your body’s completely reeling. Basically, it put me out of action for a good year.”

Once his doctors gave him the go-ahead to proceed with his normal life and career, Petit was set to release the album in late March of 2020 when the COVID pandemic threw a wrench into that idea.

A tour to support the album was nixed, and while he waited for lockdown to be lifted, he decided to release the record digitally.

“We finally got physical copies out in the fall of 2020, once brick-and-mortar stores began to open up again,” he explains.

The whole thing was this crazy double-whammy. First I had my own health issues to sort out, and then this global pandemic knocked out the rest of the world

Stephen Dale Petit

“The whole thing was this crazy double-whammy. First I had my own health issues to sort out, and then this global pandemic knocked out the rest of the world. In a way, the second thing wasn’t so hard on me because of what I’d just gone through, but it was a really insane time.”

He laughs. “Is this where I say, ‘All’s well that ends well?’”

Another thing that distinguishes 2020 Visions from most other blues albums is its sound, a unique and revolutionary sonic approach that owes as much to art rock, emo, punk, metal and even jam bands as it does to traditional blues.

On the nine-minute space-age epic “The Fall of America,” Petit exorcises demons as he explores every possible shattering cry and wail his guitar can emit.

In an equally virtuoso performance on another extended track, “Zombie Train,” he goes for broke, firing off supersonic, freak-out solos and shards of psychedelic lines while leading his ace band – bassist Sophie Lord and drummer Jack Greenwood – on a slinky, cosmic and soul-drenched jam journey.

“Sputnik Days,” co-written with his legendary friend (and quasi-mentor) Mick Taylor, is a sublime yet exhilarating dream that offers Petit a showcase for celebrating the lyrical power of bent notes and harmonics.

And those are just some of the highlights. There’s also incendiary re-workings of classics like “Steppin’ Out” and “Long Tall Shorty,” on which the guitarist goes full throttle, summoning the spirits of blues greats while fearlessly claiming the songs as his own.

I want to sound like today. There’s enough people stuck in yesterday, and that’s just not for me

Stephen Dale Petit

“Blues is the essence of what I do, but I don’t let it dictate where I can go,” Petit notes. “I just let my instinct guide me. Otherwise, I’m just re-creating what’s been done before, and what’s the point of that?

“It’s like people doing ‘Caldonia,’ which is a great song that’s been a blues standard for 50 years. On any given day, there’s a hundred bands playing it, and I think, Why would they do that, especially if they’re not going to do something new with it?

“I try to take various essences, flavors, colors and styles, but I want to bring them into the present. I want to sound like today. There’s enough people stuck in yesterday, and that’s just not for me.”

As a teenager in California, you hung out with some early metal stars of the day, including Randy Rhoads and George Lynch. Were you much of a shredder?

Not really, no. I more or less decided that I would never develop those kinds of chops. For a good while, I sat on my parents’ sofa, playing my guitar and pondering.

I’d just seen B.B. King – I even got a chance to meet him. There was something about the blues that had touched me deeply, because it’s a cry of the soul. It felt so authentic, especially when compared to the phoniness that was around at the time.

I considered all that stuff out of L.A. contaminated by the ethos of Hollywood, and I didn’t want to be a part of it. On top of that, George Lynch tried to steal my girlfriend.

Oh, well, that would sure turn you off metal.

[laughs] It didn’t help. But yeah, prior to that, I was playing lots of rock covers like everybody else – “Rocky Mountain Way” and stuff like that.

After the revelation of seeing B.B. King, how did you do your homework and absorb the blues?

It actually started with Chuck Berry. My parents listened to the Beatles and the Stones, who both name-checked Chuck. They covered him and talked about the debt they owed him. They celebrated him.

I went out and bought Chuck Berry Is on Top, which was on Chess Records, and from there I started checking out other people on the label: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter. It happened really quickly.

Whether it was Cream or Hendrix or even the Beatles, it was all about appealing to youth

Stephen Dale Petit

I imagine you felt like an outlier in L.A. Everybody was getting into the Sunset Strip shred-metal scene while you’re digging into older stuff.

I was very much out of anybody else’s orbit. I just didn’t participate in their scene. But it was a conscious decision. At first I felt a bit awkward, but the magnetic pull of the blues was too strong.

Now, you did a bit of reverse engineering. You went to the U.K. because you were inspired by their blues players, but those were the same people who revered American blues artists.

You’re absolutely right. I was getting the echo of the echo, so to speak. But the way that it was marketed, whether it was Cream or Hendrix or even the Beatles, it was all about appealing to youth. I was young – a generation out, perhaps, but I was still a youth.

How do I put this? I just thought of England and Europe as angular, whereas America was square. There was something coming out of England that felt like a way in. To me, a player like Mick Taylor was a revelation in the beginning, more than even somebody like Peter Green. Hendrix was immediate.

I was hearing all this stuff long after it was released by listening to friends’ older brothers’ records. It all just started to percolate and simmer.

But yeah, I decided to go to England because I just wasn’t thrilled with what I was getting in America.

Mick [Taylor] and I met up and hit it off. He was such an important player to me in terms of understanding overbends

Stephen Dale Petit

You became friends with Mick Taylor. How did you two meet?

I went to a show of his, and then it turned out that I knew his manager. Also, I had spoken to somebody in a restaurant adjoining the club who turned out to be his best friend. She had a dog named Roxie, and my dog was named Roxie.

The stars aligned, basically. It was fate. Mick and I met up and hit it off. He was such an important player to me in terms of understanding overbends. We all started doing two-and two-and-a-half-step overbends from hearing Crusade [by John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, 1967], specifically the song “Oh, Pretty Woman.”

Mick was 17 at the time, and I started listening to it when I was 17. I was like, Oh this guy did this at my age. Incredible!

Did Mick take you under his wing?

He did. I think he was expecting a Stones freak initially, so he was pleasantly surprised that my interest was more in the blues stuff and the John Mayall records. He toured with me as a special guest, and I think he’s on three of my albums.

The way “The Fall of America” came about is interesting: Mick was living with me. I’d just come back from a trip to L.A., where I’d seen the Kills. The band’s guitar player, Jamie Hince, is fond of hooking the thumb over the neck to make chords – an old bluesman’s trick. I thought, Wow, yeah, I should try some more of that.

I was inspired by seeing the Kills

Stephen Dale Petit

I started to noodle around, and Mick came into the room; actually, he was sort of lingering in the doorway while going to make some tea or whatever. He would listen to me sometimes, but he wouldn’t say anything.

So this one time he was listening, and I knew he was there. I was playing around with this riff, and finally he said, “That’s so powerful. It’s really intense and hypnotic.” Then he left to go into another room but not before saying, “It needs to go to E.” And that’s why it goes to an E at the end.

I was inspired by seeing the Kills, but Mick, to his credit, knew not to interrupt me till the right time. He could sense something was being born.

You also became friends with Eric Clapton. That must be pretty remarkable.

Oh yeah. We met through mutual friends. In the beginning, it was like a dream coming true, and you can’t quite believe it – you’re hanging with one of your heroes.

Then it changes and you’re dealing with a human being, and through that process, when you’re actually becoming friends, it goes through phases and you get closer and closer. All of that stuff happened.

Any preconceived notions I had of what he was like went out the window pretty early. He was nothing like what I expected.

Do you two sit down and play together?

Oh, no. No, no, that’s not happened, at least not yet.

Any preconceived notions I had of what [Eric Clapton] was like went out the window pretty early

Stephen Dale Petit

He’s commented on your playing and has been quite complimentary.

Yeah, that’s brilliant, isn’t it? It’s mind-blowing, really. You hope for it, but you tell yourself not to expect it.

What kind of impact did Eric have on your playing?

Oh, a lot. [laughs] In my journey, I got my head around overbends, so I went back to the people who started it. Albert King did overbends left, right and center. I would listen to him, but I couldn’t figure him out. This was all before YouTube. I had to do it by ear.

Now, if you overbend by two steps, the note has a different tone than if you just fret honestly on the neck. It’s not dishonest – it’s just got a whole different thing. The tone is different; the timbre of the way the string vibrates is different.

With Eric, I heard the solo he did on Cream’s “I’m So Glad,” and he’s doing different things. I was knocked out.

That and the “Steppin’ Out” solo – I was literally speechless. I know that’s an overused figure of speech, but that’s how I felt. My whole foundation was rocked. Just when I thought I might be getting somewhere with the guitar, I heard this and thought, Holy shit!

You’ve put out some terrific albums, but 2020 Visions feels like a breakthrough. The electric guitar sound is wild, trippy and dramatic, and it’s not typical of how most blues guitarists sound. And you have more than one sound.

I don’t want to sound like anybody else, and I don’t understand why other people would want to

Stephen Dale Petit

I’ve spent years thinking and working on this. To me, tone and textures are every bit as important as what you’re playing. I don’t want to sound like anybody else, and I don’t understand why other people would want to.

What I’m seeking is some sort of a sonic texture that’s unique. It’s not quirky or weird, like it’s a novelty or gimmick; rather, it’s related to what the music is addressing. It’s a style. It’s a sonic style as opposed to a musical style.

It’s easy to say, “I want to sound unique.” It’s quite another thing to pull it off.

It is. One big thing that’s helped me was getting an original Marshall JTM45. It’s part of the toolbox that enables me to do this. I hate to say that, because the amp was stupidly expensive.

I didn’t want it to be true, but the way those amps were designed with the negative-feedback loop, it stacks harmony when you’re sustaining a note. It’s more of a musical instrument than just an amp.

Let’s talk about some of the songs on the album. The title track is blues, but it’s got a very pronounced punk rock side to it.

Sure, sure. I mean, I’m playing blues licks, no doubt, but it’s got another thing. You know, I never really used to like Iggy Pop until I read that he went to Chicago and tried to be a blues guy for, like, six months. Then I kind of understood.

I take my sensibilities from the British musicians of the ’60s and ’70s. They were making new art

Stephen Dale Petit

The guitars on the song are trashy and reckless. It’s like they collide off each other.

As well they should. The guitars on the chorus are just driving and out of control, but there’s the call-and-answer guitar to the vocal. It’s got a bluesier, warmer sound. But I’m purposely trying to smear notes, bitter to sweet.

You’re very rough with your guitar on “The Fall of America.” Every riff, power chord and solo is brutal. It’s not festival-tent blues.

It’s designed not to be that at all. There are people who can do that beautifully and brilliantly, and my hat is off to them. It’s just something that doesn’t interest me. I guess I take my sensibilities from the British musicians of the ’60s and ’70s. They were making new art.

That sounds pretentious, but they weren’t just making an archive of what was happening in the room. They were using all the tools of technology to create something unique in that moment, and it was as far from field recordings as you could get.

At nine minutes long, the song is epic. For much of it, it seems like you’re having fun exploring tones.

Oh, I am, I am! Yeah, we went on for a bit, but hey, America’s a big country. [laughs] The subject of what’s going on is a big subject. I’d never written a nine-minute song before, but it went where it wanted.

“Roxie’s Song” is altogether different. It’s a tight, beautifully constructed instrumental.

Yes, Roxie was my miniature schnauzer, and she died. With this record, there was a musical concept. I wanted it to be an honorific homage to the bent note on the guitar.

“Roxie’s Song” has a really long bend, which is the sad part. Obviously, I was gutted that my dog was dead, and I was missing her like nothing else.

But what about the happy times? So there are middle bits where it’s sort of like in summer grass and how she had to hop around to be seen. There are fun bits and moments of exhilaration, like how you play chase with your dog, or how they go crazy when you walk in the door.

How did you and Mick Taylor collaborate on writing “Sputnik Days”?

That was another one of those times when he heard me working on something, but rather than lingering in the doorway, he felt compelled to pick up a guitar.

He co-wrote it with me. It sums up what I aspire to: It’s rooted properly in deep blues while living in the present and being aware that we have tomorrow to look forward to.

One song that is very reverential to the blues is the very short instrumental “On Top.”

Yeah. That’s Sophie Lord playing bass and doing some serious chording – lovely tone clusters as the bedrock. I don’t mind going there – you know, the reverential thing – but it’s why it’s short as well.

“Zombie Train” has a bit of funky soul to it. It’s got a bit of a ’70s feel, but again, it sounds very current. And it’s a great showcase for everybody in the band.

Oh, yes, for sure. That’s another one on which Sophie is front and center. It was sort of showcased for the bass. Both Sophie and Jack Greenwood play brilliantly throughout the record.

“Zombie Train” is this spoken-song verse, and I really loved being able to stretch out on the guitar solos. It’s another long one, and it’s closer to us being a jam band or something.

You have all these Beatles connections. Ringo Starr does a spoken intro on the song “The Ending of the End,” the album’s artwork was done by Klaus Voormann, and you’re photographed by Pattie Boyd.

The Beatles are like blues songs with pop choruses

Stephen Dale Petit

Yeah, it’s something. Actually, Pattie photographed me for two album covers. You know, my parents played the Beatles; they were part of my musical journey.

When I met Jimmy Page the first time, we talked through it and he agreed. He said, “Well, yeah, they’re rooted in the blues.”

The Beatles are like blues songs with pop choruses. “Can’t Buy Me Love” is a blues progression, and so is “She’s a Woman,” “Lady Madonna,” “I Feel Fine” and on and on.

“Yer Blues,” obviously.

Sure. That was a great one.

You recently started playing the Gibson Custom Modern Flying V.

I did. That’s a whole different experience because it’s so lightweight, and it kind of folds into you. You’re almost wearing it. It’s an insane guitar, and I love it.

On 2020 Visions, I mostly played a cherry-red [ES-]355 reissue. It’s the star of the record. It’s like the Cadillac of guitars. It’s semi-hollow, and it just feels like a proper guitar. I grew up hating 355s. I thought solid-body guitars were the only real guitars. Lately, I’ve done a complete turnaround.

So much current blues has become formulaic – the sounds and just the concept of what a blues record in the modern age should be

Stephen Dale Petit

Is there anybody in the current crop of blues guitar players who stands out to you?

There’s some great players. Connor Selby, Toby Lee – those are two off the top of my head.

It’s hard for me to criticize anybody, because I think anybody doing it should be applauded. If they’re out there and playing, they’ve already accomplished so much.

At the same time, so much current blues has become formulaic – the sounds and just the concept of what a blues record in the modern age should be.

A lot of that has to do with people being concerned about airplay. I’m unsure how it all happens. Is it the artist? The producer? These people can be great players, but it’s hard for me to listen to another blues song that’s produced the same way or with the same approach.

Sometimes I can’t get past it, but that’s a personal problem. It’s got nothing to do with anybody else.

Order Stephen Dale Petit’s 2020 Visions here.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.