All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

*** Before you get stuck in, we recommend bookmarking this page so you can easily return at a later time ***

Even if you know a lot of cool riffs and licks, you may find yourself stumped when it’s time to come up with something creative on the fly. If in such moments you find yourself relying on tired phrases, mundane chord voicings and static, go-nowhere, copycat riffs, take heart!

This lesson will shed light on the fine art of riff crafting and help you make the most of those opportunities.

The Boogie Riff

Many consider Chuck Berry to be the first rock and roll guitar god, and with good reason. His lead- and rhythm-playing styles, not to mention electric guitar tone and showmanship, were so influential that they have withstood the test of time.

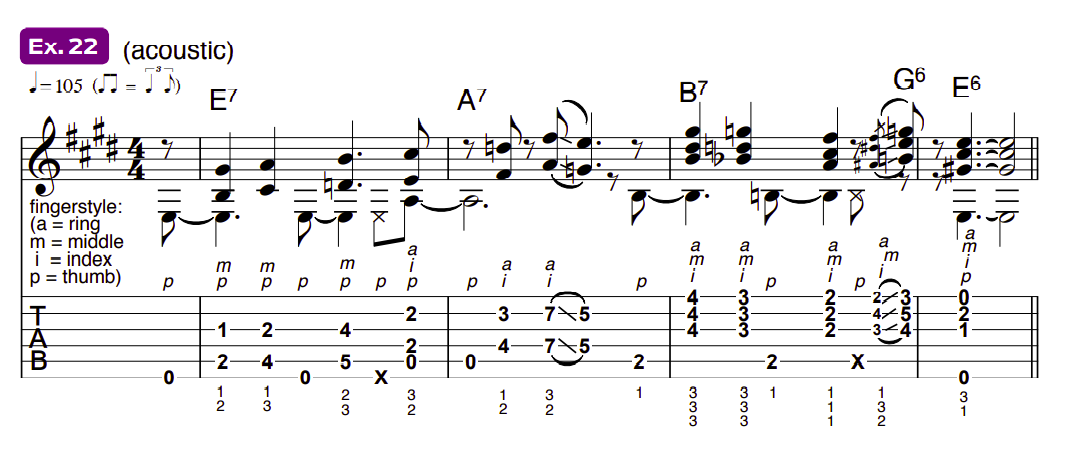

Ex. 1 is based on Berry’s riffing style in songs such as “Johnny B. Goode” and “Sweet Little Sixteen.” Essentially, it’s a root-5th C5 power chord (C, G) alternating with a root-6th C6 grip (C, A,) and fortified by a low E-string attack on the C root note.

This root-5th/root-6th figure, often referred to as a “boogie riff,” is a common fixture in blues music and early rock and roll. Equally effective in shuffle rhythms as it is in a straight-eighths grooves, it can be recast in a variety of combinations. It’s also easy to transpose to any key, can be used over a variety of chord types (C5, C and C7) and sounds good with just about any tone, from clean to high-gain.

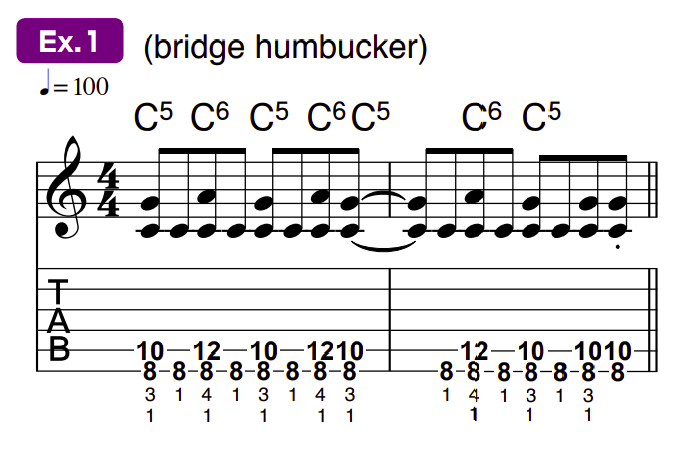

Ex. 2 is another popular form of the boogie riff. This one uses the same two grips (C5 and C6) but tosses in a third voicing for extra flavor. Analyzed as C7 in the notation, it’s actually an incomplete chord that suggests the full tonality of a C7 chord (C, E, G, Bb) with just the root and b7th (C and Bb). Reaching that Bb note on the A string’s 13th fret requires quite a stretch for your pinkie, but it’s well worth the effort. (It’s easier if you lift your ring finger off the fretboard.)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Listen to the Beatles’ famous cover version of Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” for a clear example of this type of riff in action.

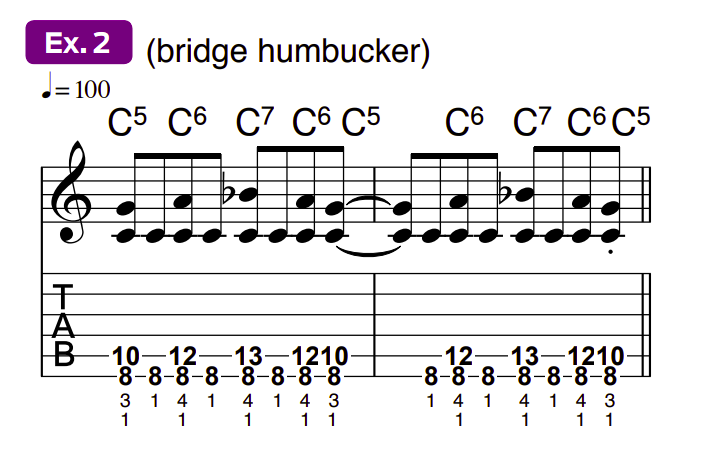

At first glance, Ex. 3 appears quite convoluted, but it’s actually a revved-up version of the root-5th/-6th/-b7th boogie pattern from the previous example. The extra notes on the low E string (Eb and E) supply a bluesy, minor-major – minor 3rd-to-major 3rd – “rub.”

Listen to Jimmy Page’s riffing in Led Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll” and Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “The House Is Rockin’” for permutations of this riff.

Power Chords, Inversions & Slash Chords

Few would argue that the power chord – a two-note entity consisting of the root and 5th – rules the hard rock world. Indeed, entire songs have been written around the two-note wonder, shifted around the fretboard to different notes. Often these shapes fit the bill for getting the point across, but sometimes a little extra flair is needed.

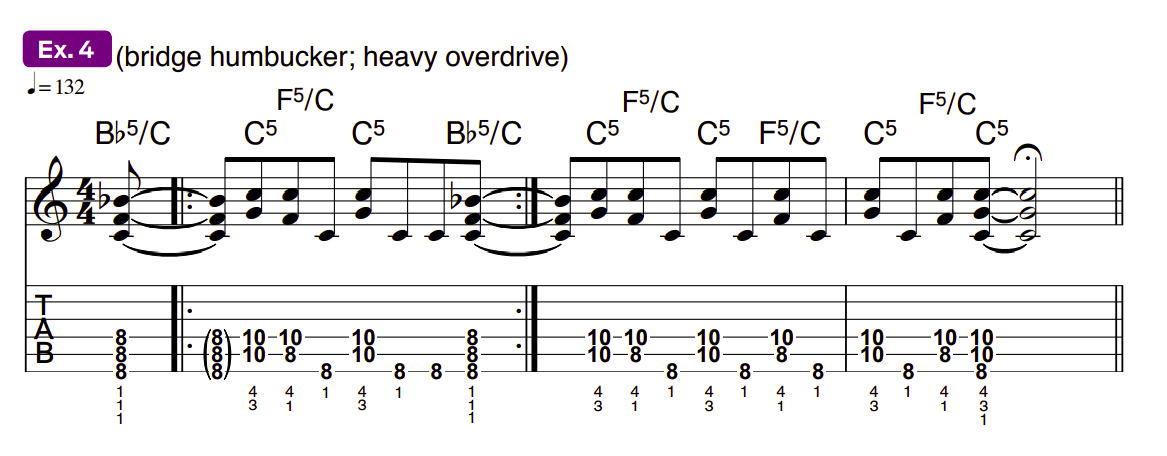

Ex. 4 takes a common root-5th-octave voicing of a C5 chord (C, G, C) and, with the help of some strategically planned fret-hand “finger raising,” transforms it into a captivating riff that’s bursting with inverted power-chord infusions.

From a physical standpoint, here’s what’s happening: the index-ring-and-pinkie grip produces the familiar C5 voicing; lifting the ring finger creates F5/C (make sure your index finger is barred across the bottom three strings), and lifting both the pinkie and the ring finger gives you the Bb5/C chord.

With a little ingenuity, these three voicings can produce a wide variety of options. You may even want to combine them with the boogie patterns from the previous examples.

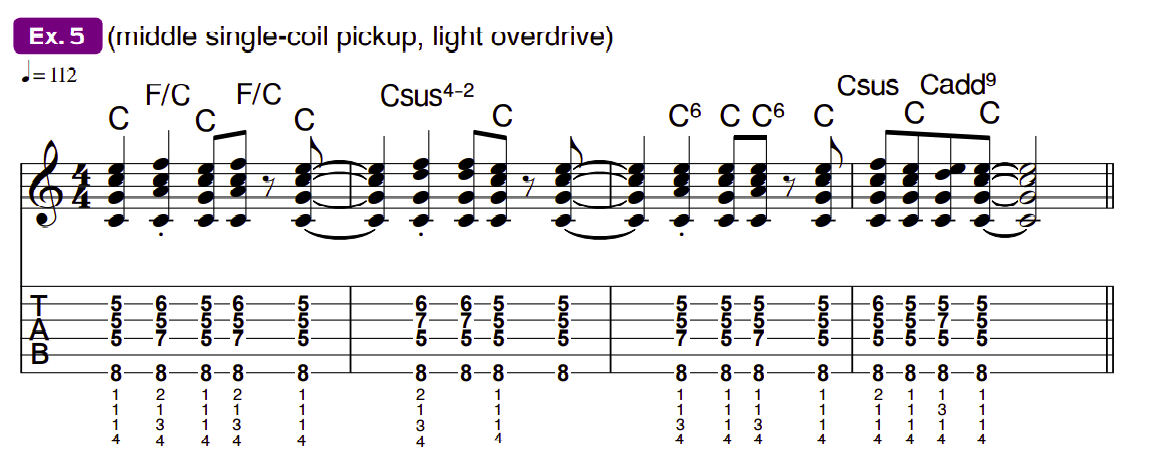

Ex. 5 is inspired by one of the most influential riff meisters in the classic rock vein, the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards. This example is a standard-tuning version of the guitarist’s five-string open-G–tuned riff style. (Richards removes his guitar’s low E string and tunes the remaining strings, low to high, G, D, G, B, D).

The initial C chord voicing is the anchor for this example. Fretting the root note with your pinkie may feel uncomfortable at first, but it allows for a variety of chord extensions by planting the middle and/or ring fingers on designated frets in front of an index-finger barre across the D, G and B strings.

Try it out, and you’ll hear elements of Rolling Stones classics like “Street Fighting Man,” “Gimme Shelter,” “Honky Tonk Women,” “Brown Sugar” and “Start Me Up.” The beauty of this grip is that it’s easily transferable to virtually any key on the fretboard by simply shifting it up or down to various positions.

Thirds and Beyond

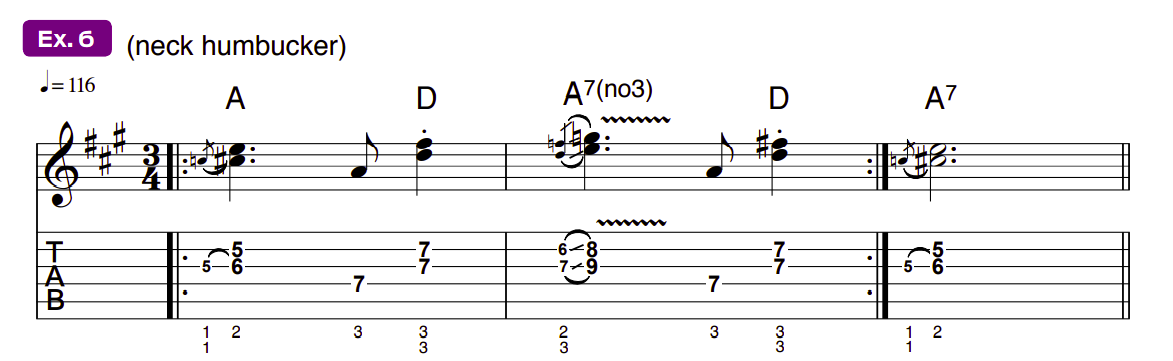

Ex. 6 introduces a “launching pad” motif that lies at the heart of many blues, funk, jazz and rock riffs. The example is based on the saxophone harmony riff (courtesy of John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley) from Miles Davis’ jazz-blues classic “All Blues.”

The dyads on the G and B strings are harmonized thirds from the A Mixolydian mode (A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G), and the hammer-ons and slides are chromatic “lower neighbor” grace-note embellishments. The solitary A note at the 7th fret on the D string fortifies the tonic, or root, of the key and helps to imply a bluesy A–D–A7–D progression.

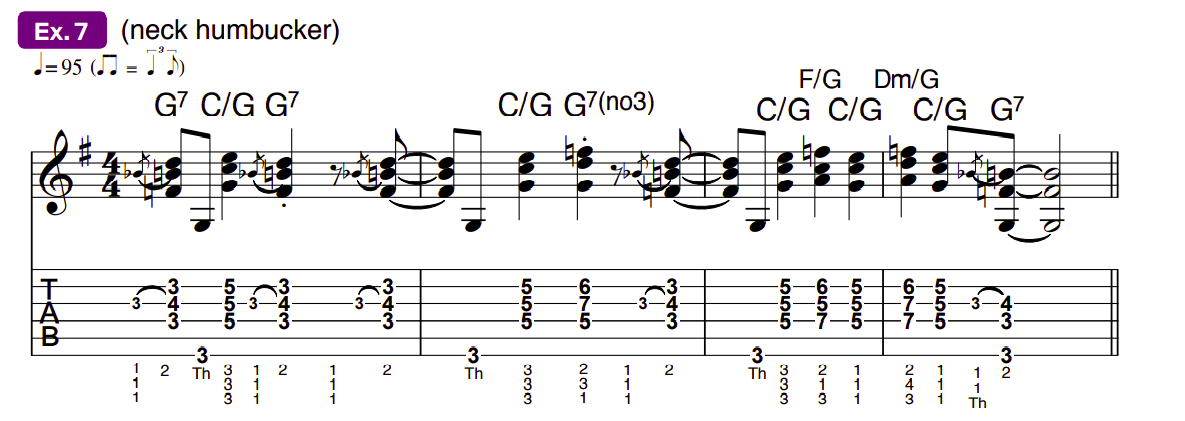

Ex. 7 is based on the principles set forth in the prior example but is in the key and modality of G Mixolydian (G, A, B, C, D, E, F) and set in a 4/4 shuffle groove. The G-and-B-string dyad shapes are again at play here, but notes are added along the D string, creating full triads and partial 7th chord shapes.

Incidentally, if you’re playing with a bassist, you can omit the thumb-fretted G bass notes on the low-E string and concentrate on the triple-stops. Again, once you’ve mastered this example, it’s a breeze to transpose it to other keys along the fretboard.

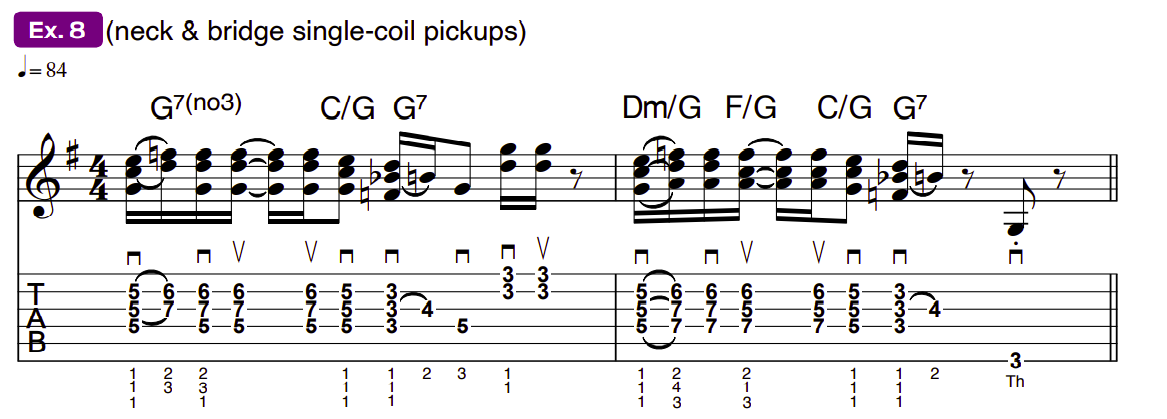

Also in the key of G, Ex. 8 pushes the envelope a bit further with a funk-rock-style example based on players such as Jimmy Page (Led Zeppelin), Joe Walsh (Eagles, Barnstorm and the James Gang) and Joe Perry (Aerosmith). Although a few other chord partials are added, the “All Blues” dyad figures are still at play.

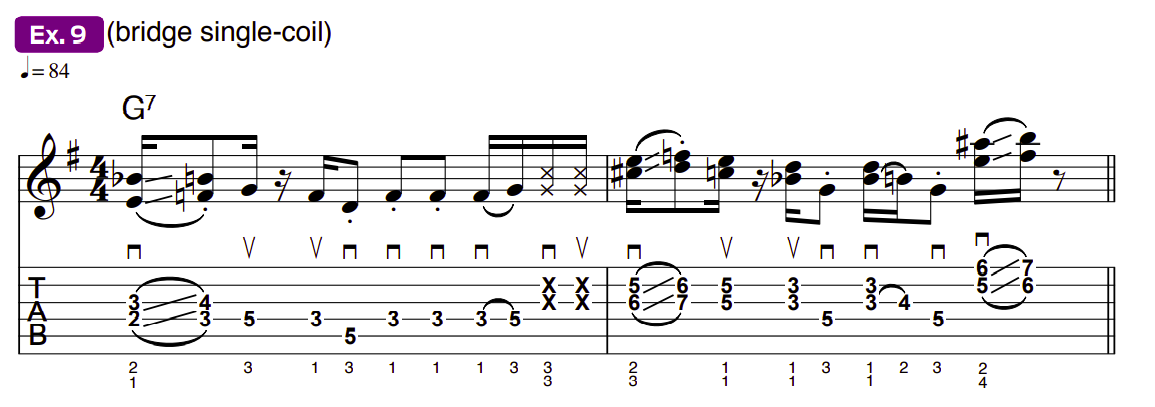

Ex. 9 is in the funky R&B style of such songs as “Cissy Strut” by the Meters (featuring Leo Nocentelli) and “Cut the Cake” by the Average White Band (Hamish Stewart, Onnie McIntyre and Alan Gorrie). Indicative of that style, there are more single-note passages tossed into the mix here. However, upon close inspection, those Mixolydian dyads are still present and accounted for.

Pentatonic Riffing

Pentatonic scale patterns can provide finger-friendly terrain from which to draw out chordal riffs and fills. All that’s needed is a system to rely on.

Ex. 10a illustrates an elongated box pattern of the D major pentatonic scale (D, E, F#, A, B), while Examples 10b and 10c depict primary voicings of D major chords cultivated from the pattern itself. The process involves playing either of the chord shapes and then crafting a fill or embellishment drawn from its overlapping pentatonic pattern.

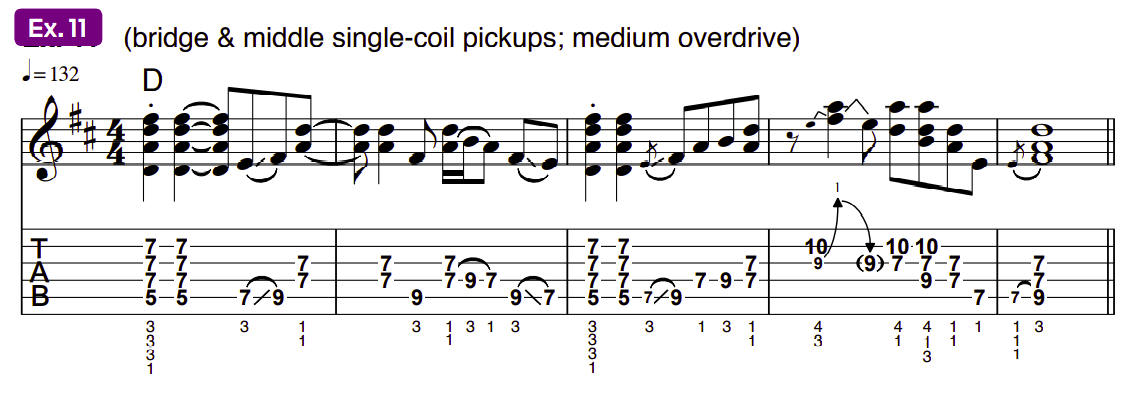

Ex. 11 demonstrates this procedure with a passage reminiscent of the southern-rock staple “Gimme Three Steps” by Lynyrd Skynyrd (Gary Rossington, Allen Collins and Ed King).

These are classic moves and can be found in such songs as “Peace of Mind” by Boston (Tom Scholz), “Rock and Roll All Nite” by Kiss (Pal Stanley and Ace Frehley) and “The Wind Cries Mary” by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

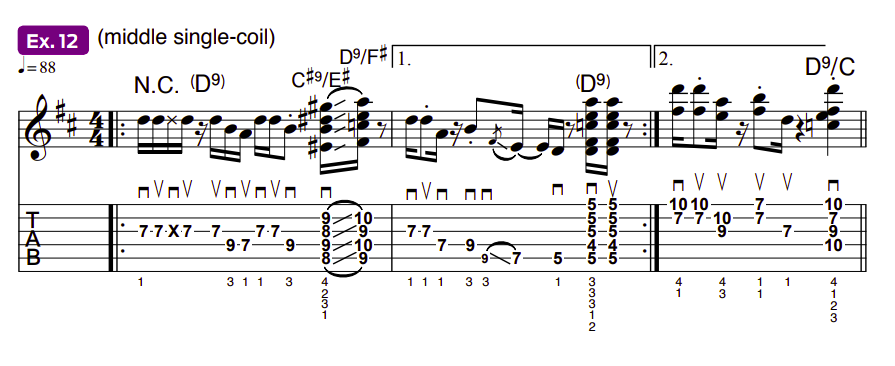

Ex. 12 is also drawn from the pentatonic framework illustrated in Examples 10a–c. This riff is in the same funky R&B vein as Ex. 9, and offers a mini-lesson in how single-note rhythmic punctuation can replace chordal maneuvers.

Notice how the complex chord voicings make up for the stark contrast of the single-note passages. If you’re wondering why there are so many upstrokes in the notation, it’s to keep your strumming hand in the “16th-note pocket” of the groove. Use downstrokes for the first and third 16th notes of each beat and upstrokes for the second and fourth 16th notes.

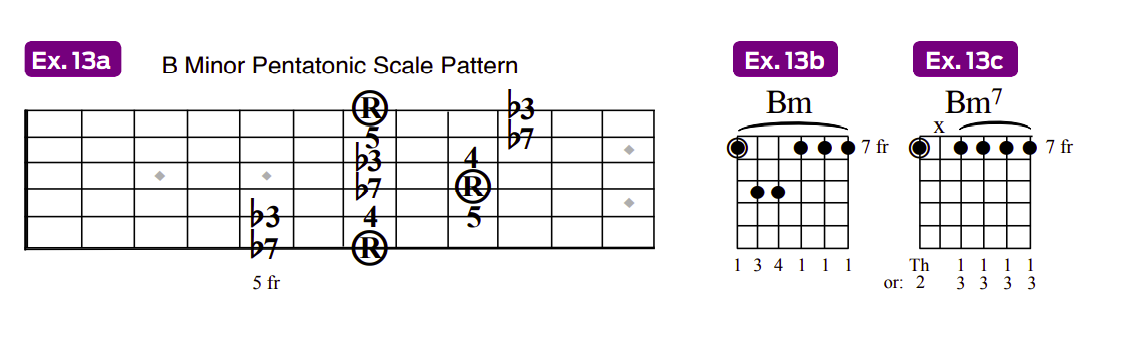

Now let’s look at a minor pentatonic approach. Ex. 13a shows the D major pentatonic scale’s relative minor scale, B minor pentatonic (B, D, E, F#, A), which is made up of the same five notes, now oriented around a B root. Examples 13b and 13c show two primary barre-chord voicings crafted from the pentatonic pattern: Bm and Bm7.

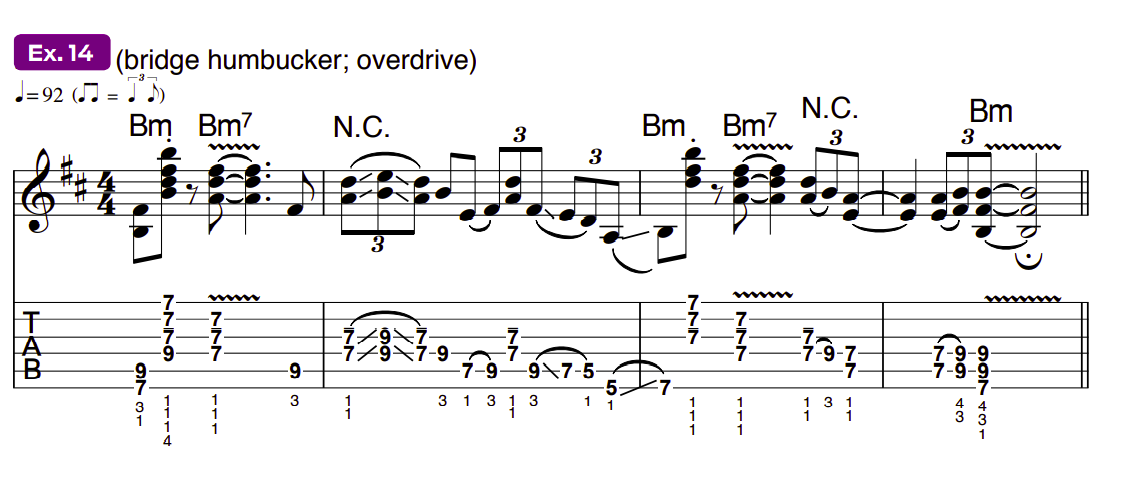

Ex. 14 offers a blues-rock example of the minor pentatonic process in action with a riff in the style of beefy-tone rockers such as Robin Trower (“Bridge of Sighs”), Billy Gibbons (“Cheap Sunglasses”) and Pat Travers (“Snortin’ Whiskey”), and Ex. 15 presents a funky and flashier approach to the chord-and-overlapping-scale approach.

In both examples, a fat chord voicing sets the scene, and fills ensue. This riffing method – “play the chord on the downbeat and fill in the second half of the measure” – is particularly effective in power-trio situations, where the guitar is the only harmonic instrument.

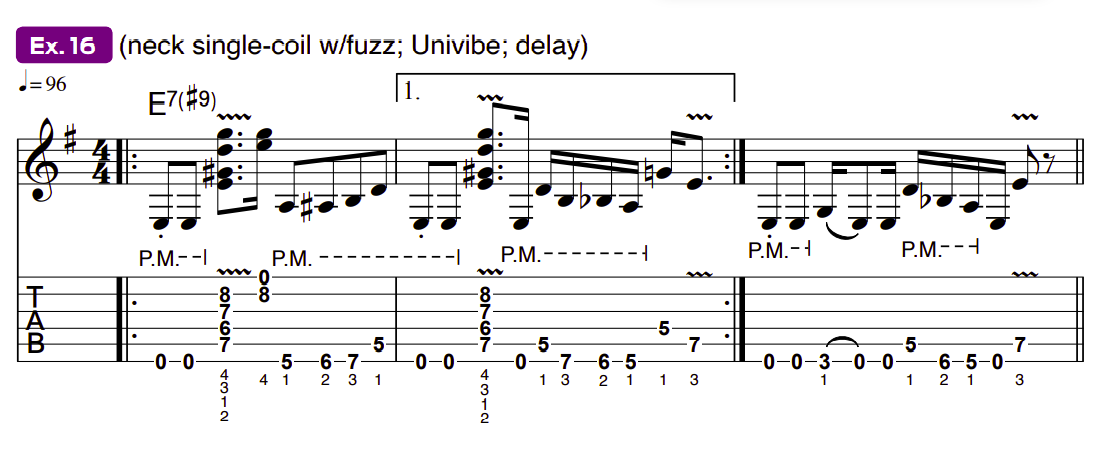

“Regional” Scale Embellishment

The overlapping-pentatonic process described above can be applied to virtually any chord voicing and its scale counterpart. For instance, Ex. 16 peppers an E7# 9 voicing with notes from a nearby “mini pattern” of the E blues scale (E, G, A, Bb, B, D). Straight out of the Jimi Hendrix book of riff rock, it’s drawn from the feel and structure of the riff work from two of his early trademark songs “Foxey Lady” and “Purple Haze.”

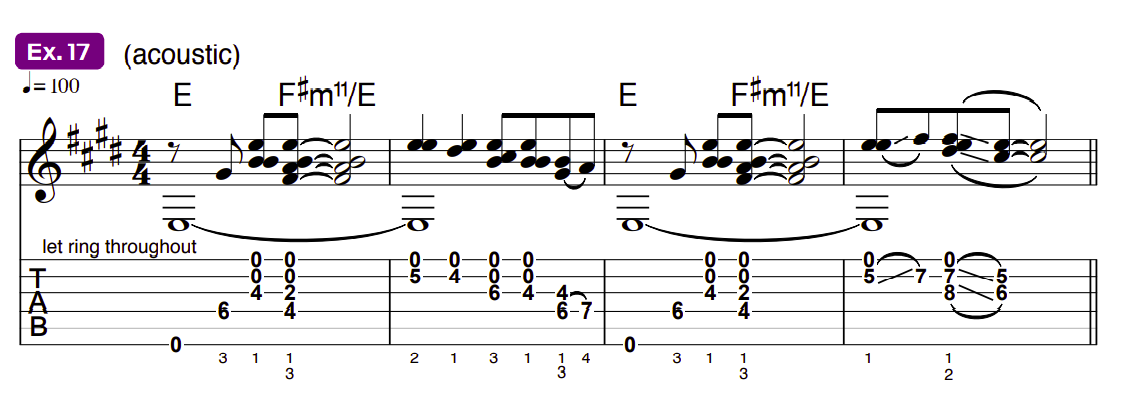

Ex. 17 offers solace from the heaviness of the previous example with a lovely acoustic passage. A pair of shimmering chord voicings (E and F# m7/E) set the stage in bars 1 and 3, with notes from “regional” patterns of the E major scale (E, F#, G#, A, B, C#, D#) dispatched in “call-and-response” fashion in measures 2 and 4. Notice the use of the droning open high E string to add “sparkling” reinforcement to the scalar passages.

If you’re intrigued by this chord/scale handoff style of riffing, experiment with some of your favorite patterns. For example, play a 5th-position Am or Am7 chord and then a short fill using notes from the overlapping A natural minor scale (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) or A Dorian mode (A, B, C, D, E, F#, G).

Chord Fragments and Arpeggiating

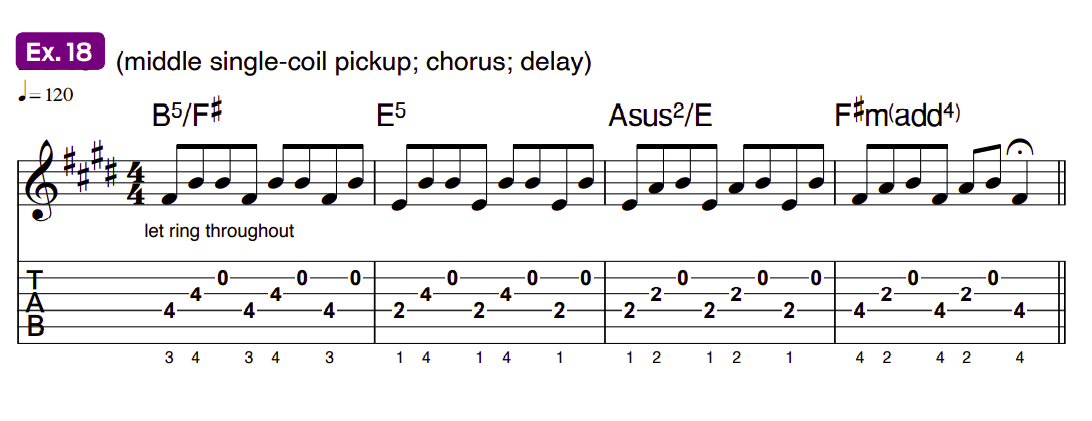

Ex. 18 is inspired by tactics employed by players such as U2’s The Edge (“With or Without You”), Eric Johnson (“When the Sun Meets the Sky”) and modern jazz great Pat Metheny (“Phase Dance”), all masters of utilizing minimalistic voicings to outline chord changes.

Harmonically, this example is loosely based on the underlying progression from “Pride (In the Name of Love)” by U2. Designed to be played with a bass player marking only the basic root structure (B–E–A–F#), the shifting dyad groupings on the D and G strings suggest that fuller voicings are actually being played. The arpeggiated structure and droning open-B string produce a rhythmically offset, hypnotic mood.

Throw in some chorus and delay effects, and the outcome is much greater than the sum of the parts.

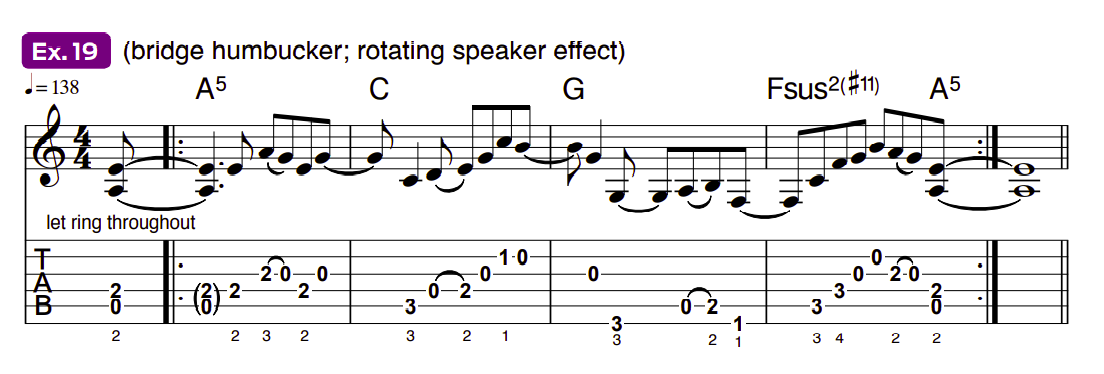

Ex. 19 illustrates a simpler, but no less effective approach to arpeggiated riffing. This one is a tip of the hat to Elton John’s longtime guitarist and musical director, Davey Johnstone. Fashioned after his crafty open-position riffing in “Love Lies Bleeding,” from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, the example is based on standard open chords with note embellishments drawn from the 1st-position pattern of the A natural minor scale. Yes indeed, Fsus2(# 11) is diatonic to the key of A minor!

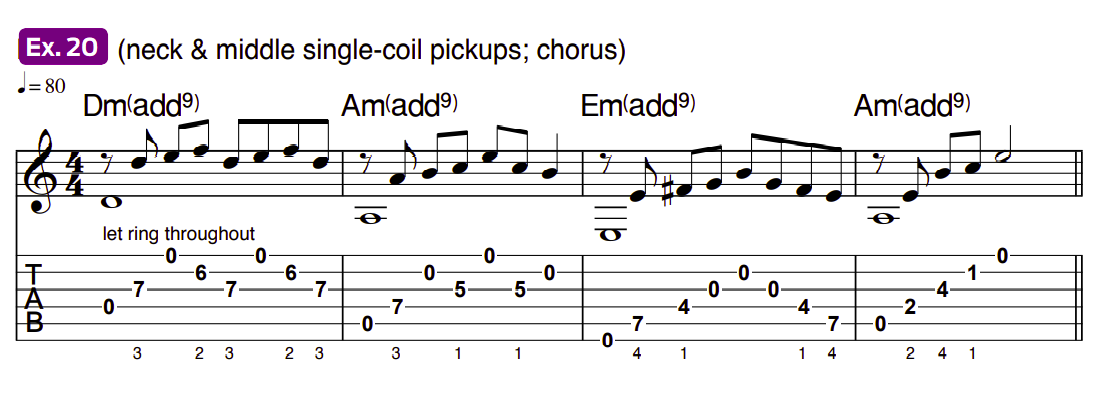

Ex. 20 is a moody, dichotomous example that mixes elements of contrasting styles, from Jim Croce’s acoustic ballad “Time in a Bottle” to Def Leppard’s “Hysteria” and Pink Floyd’s “Us and Them.” Notice how the arpeggiated patterns create scalar melodies derived solely from the unique chord voicings.

Final Advice

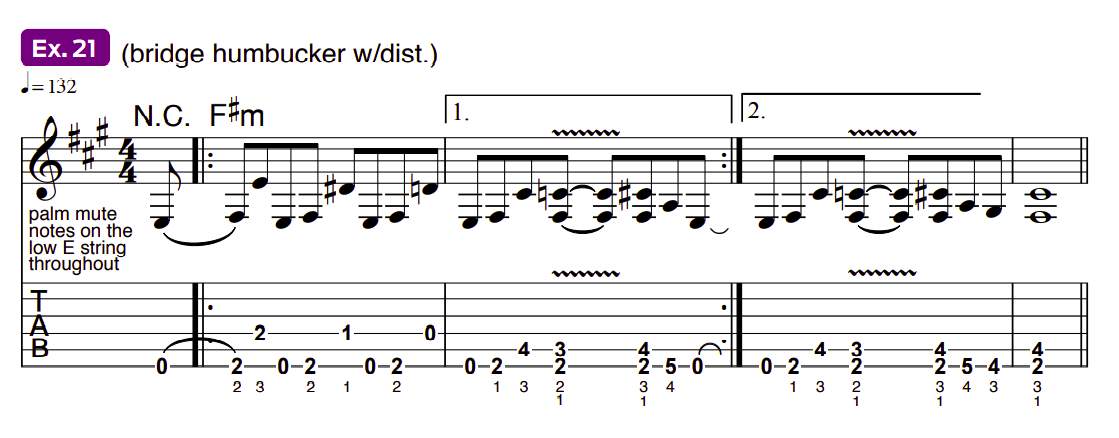

Seeking inspiration from unlikely sources can spark your creativity and help you break out of your comfort zone. Case in point: The low-string hard-rock riff example in Ex. 21 is based on the rhythmic and chordal structure of the old big-band classic “The Best Is Yet to Come,” famously sung by Frank Sinatra, but stylistically it’s more akin to something Living Colour’s Vernon Reid would come up with!

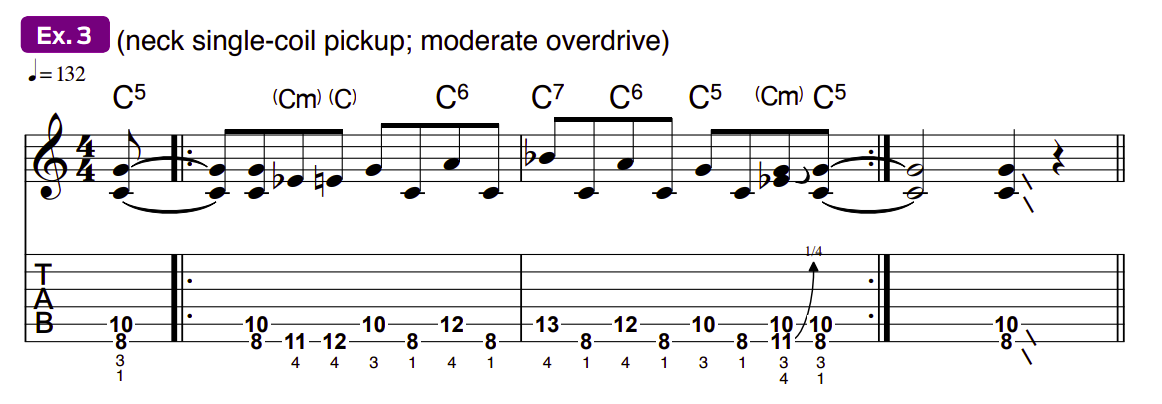

Ex. 22 closes this lesson with a blues comping figure that’s also inspired by a surprising source, in this case, the distinct rhythm structure of Ritchie Blackmore’s immortal riff from Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water.”