Played by Jimmy Page, Andy Summers, Pat Metheny and More, Roland’s Quirky GR Guitar Synths Were Surprisingly Versatile Creative Tools

Guitar synths didn’t dominate popular music, but it wasn’t for Roland’s lack of trying.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, the synthesizer threatened to take over popular music, and legion were the pundits who lined up to ring the electric guitar’s death knell.

Then, just as guitarists were getting fit to burst with oscillator envy, Roland Corporation swooped in to save the day.

Introducing what were arguably the most functional and genuinely usable guitar synths yet to hit the scene, the Japanese music-electronics company presented a series of impressive modules that culminated in the whopping GR-700 of 1984.

While Roland’s guitar synth didn’t dominate popular music as a result, it wasn’t for a lack of trying.

Guitarists have been trying to make their instrument of choice sound like something other than itself ever since a pickup was first introduced to an amplifier.

Early players took aim at trumpets, saxophones and trombones. Loud, brash and packed with raspy character, they excelled as soloing instruments and let you be heard centerstage in a way that the early guitar rigs could not.

The fuzz box and wah-wah pedal were among the first efforts to make six-string electrics mimic brass instruments, though they became so much more in creative hands.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Soon after, more all-encompassing efforts hit the scene in the form of several iterations of “guitar organs” that were invariably packed with confusing controls and switches.

The game was on.

Once the keyboard-based synthesizer started making inroads into popular music in the late ’60s and early ’70s, however, that was the sound to beat – and guitarists badly wanted some of that otherworldly sonic goodness.

Hit-and-miss efforts came from the likes of the Hammond-Innovex Condor Guitar Synth of 1970, and several others before and after.

But it wasn’t until Roland entered the game in 1977 with the GR-500 system that many guitarists sensed that a true guitar synthesizer had finally arrived.

The GR-500 system consisted of the synthesizer module of that name and the dedicated GS-500 guitar, connected to it by a 24-pin cable.

The rig was functional but not particularly user-friendly. The GR-500 synth was a tabletop unit that required hands-on twiddling for patch changes, and the guitar was a somewhat cumbersome Les Paul-inspired affair, with a host of knobs and switches mounted to a big plastic plate on its lower bout, not radically different from the equally DIY-looking Gibson Les Paul Recording model, which was not a synth guitar.

The GS-500 was made in the FujiGen Gakki factory in Japan

The GS-500 was made in the FujiGen Gakki factory in Japan, which also made guitars for Greco, Ibanez and other notable brands.

In addition to the six-segment pickup (often called a hexaphonic, or divided, pickup) that sensed each individual string to trigger the synth unit, the GS-500 carried a single traditional electro-magnetic humbucking pickup in the bridge position, which was often considered a weakness of the design and didn’t do much for it doubling as a traditional electric guitar.

The large GR-500 synth control unit allowed the creation of several synth-like sounds by applying filters and effects to all six strings in its Polyensemble and Bass sections, but true synthesis as we know it occurred only in the monophonic Solo Melody section, which had a voltage-controlled oscillator (VCO), filter (VCF), amplifier (VCA) and low-frequency oscillator (LFO) for modulation, along with facilities to shape dynamics (i.e., an envelope) and the audio wave, much like a standard keyboard-based mono synthesizer.

The whole rig sounded pretty good when used right, but it was overly cumbersome from a guitarist’s perspective and didn’t gain much traction in the market beyond the bold experimentalists who gave it a shot.

It didn’t help that the rig cost nearly $1,000 in 1977, a sum that has the purchasing power of approximately $4,700 in 2022.

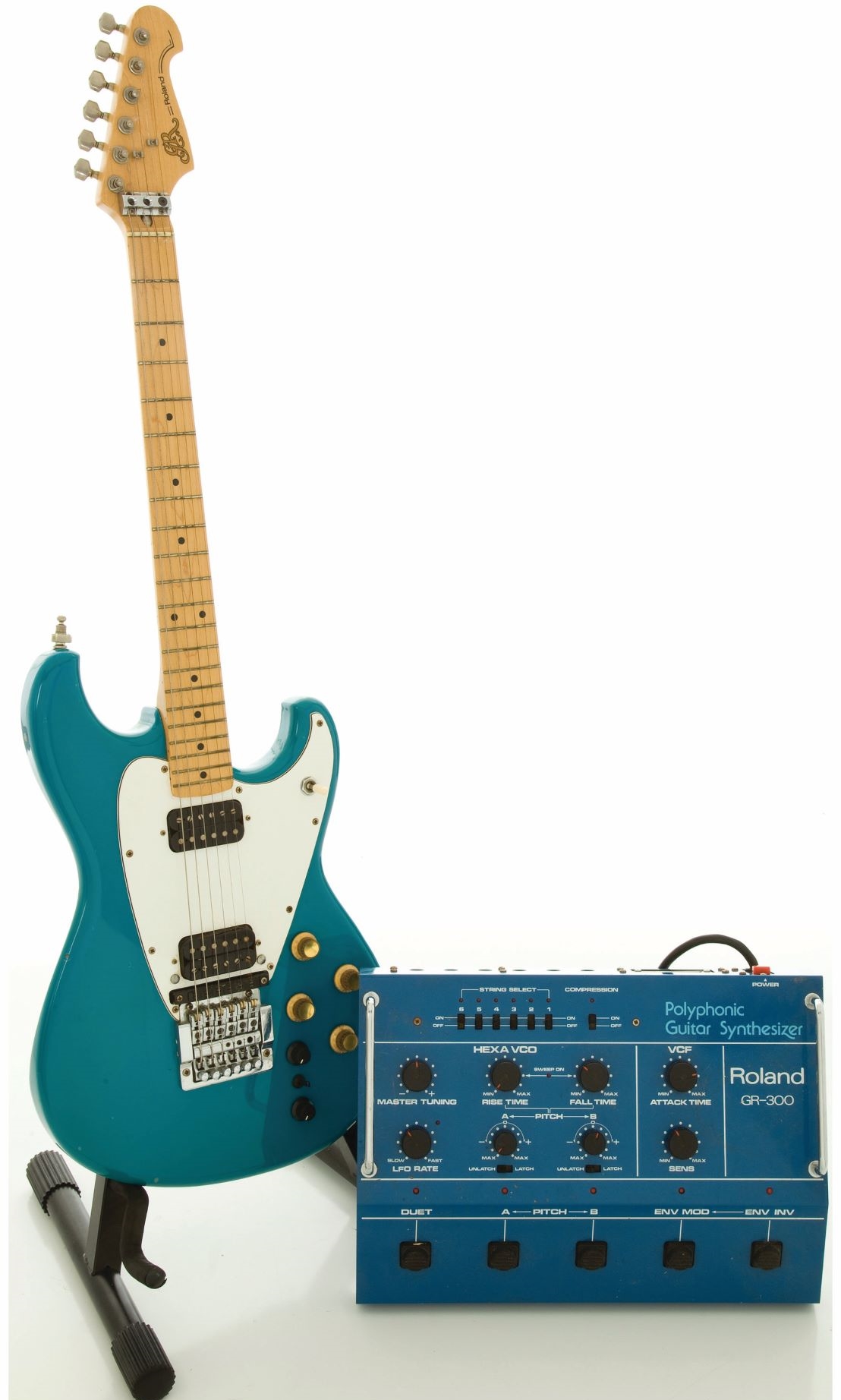

In 1980, Roland released the simpler GR-100 floor unit, followed by the similarly styled but more feature-laden GR-300 Polyphonic Synthesizer.

Both were far more intuitive for guitarists to use, and very relatable for players familiar with the larger effects pedals that were already proliferating under foot.

As basic as the GR-300 might have appeared when compared to keyboard synths available at the time, it offered a surprising amount of sonic power. Each string signal from the hexaphonic pickup had its own genuine VCO, while LFO rate and Hexa-Fuzz could also be applied at will.

There were also controls for VCF attack time and sensitivity, and decay was responsive to your playing technique, resulting in a feel far more guitar-like than the electronically controlled decay used in traditional synths.

In addition, the GR-300 had foot switches for on-the-fly selection of Duet (which added the fundamental of the guitar string pitches to the VCO), Pitch A and B (two pitch presets), Env Mod (created a “wow” effect by sweeping the filter cutoff up, and then down) and Env Inv (inverted the “wow” effect to sweep the cutoff frequency down, and then up).

The GR-100 and GR-300 were partnered by three new FujiGen Gakki-made guitars: the Stratocaster-like G-505, with three single-coil pickups; the set-neck, asymmetrical-double-cutaway G-303, with dual humbuckers; and the neck-through G-808, a seemingly Alembic-inspired creation based on the existing Greco GO1000 model, also with dual humbuckers.

Two years later, the dual-humbucker, bolt-neck G-202 joined them.

All had Roland’s hexaphonic pickup mounted just in front of the bridge, and carried a simpler and more intuitive control section.

Each also had the ubiquitous 24-pin connector for the cable that sent voltage-control from the guitar to the synth unit.

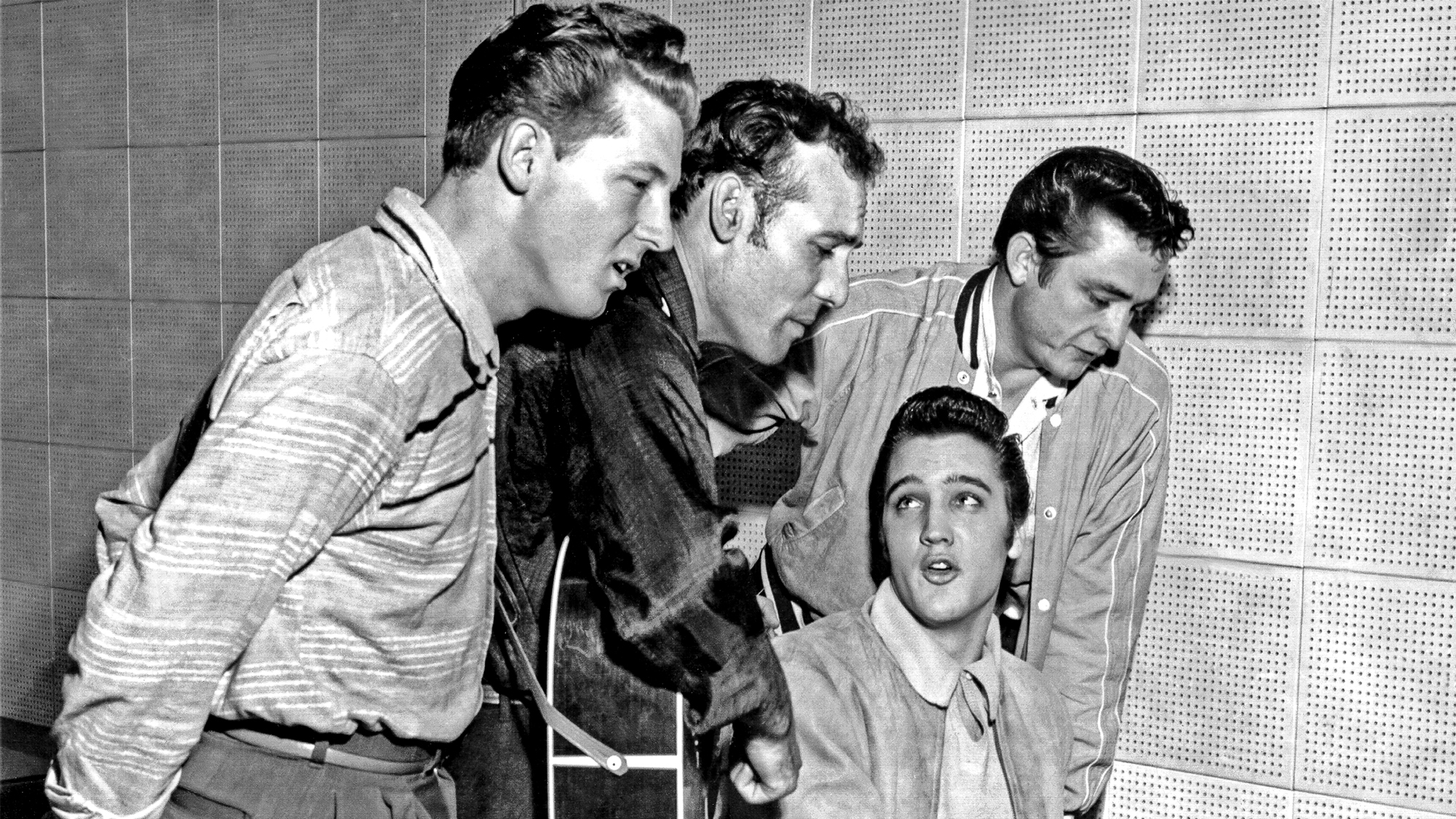

For many players who noticed such things back in the day, the G-808 and GR-300 are probably most familiar due to their use by Pat Metheny.

The jazz guitar player wholeheartedly embraced the technology (though it didn’t entirely replace his beloved ES-175), and he even later modified the G-808 guitar controller for use with a far more complex Synclavier synthesizer.

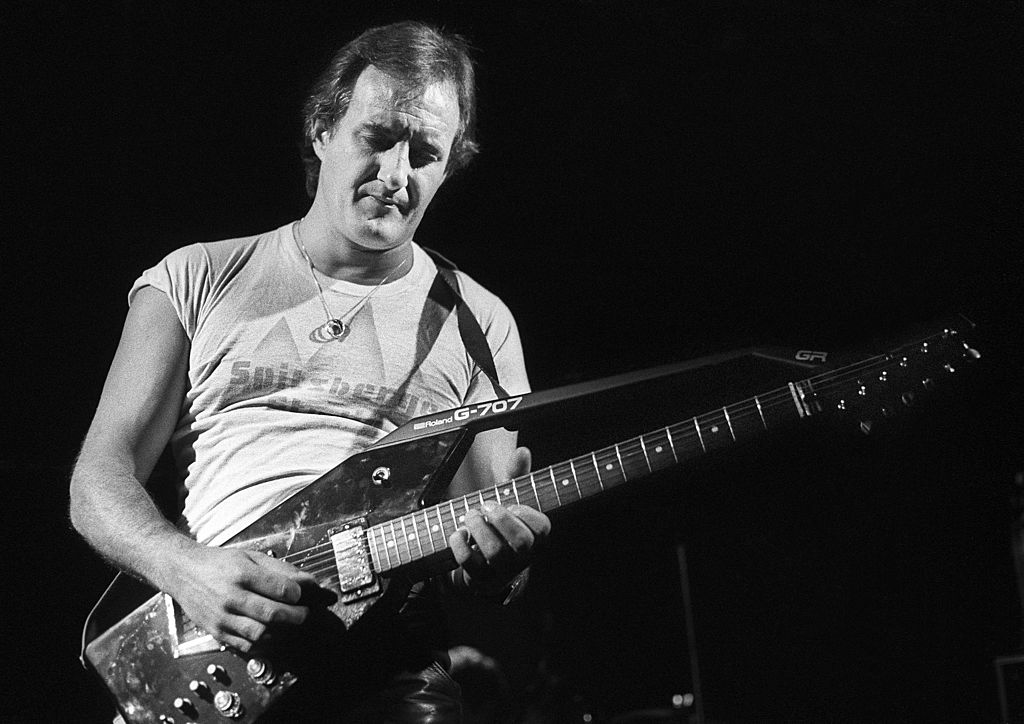

In 1984, Roland shot its last major broadside at the concept of the guitar-control-plus-synth-module rig in the form of the GR-700 and G-707 pairing.

The latter was an unashamedly modernist odd duck with a wedge-shaped body and a carbon-fiber stabilizer bar extending above the neck and connected at the headstock to improve rigidity (did we once think all guitars would soon look like this?).

By all accounts it actually performed very well, but it was clearly an awkward beast to play as well as to look at, in the eyes of many observers.

Plenty of synth-curious guitarists eschewed it in favor of the existing G-202, G-303, G-505 and G-808 guitar controllers, which partnered just fine with the GR-700.

But the synth unit itself represented a quantum leap in functionality and sound processing over its predecessors.

Packing a true polyphonic synth engine derived from Roland’s existing keyboard-controlled JX3P, the GR-700 offered two DCOs per voice for each of its six voices, plus independent envelopes for each voice, along with several other advanced functions, such as programmable memory and the first MIDI output on any Roland guitar synth.

Eleven foot switches provided access to banks, presets and editing functions, while the previous units’ knobs had given way to a control screen with multi-function touch-buttons and an LCD readout.

There was also an attachable PG-200 unit from Roland’s JX3P synth to make programming easier in an age before computer-based gear editing programs were available.

John Abercrombie, Robert Fripp, Al DiMeola and Jimmy Page all made use of the G-707/GR-700, and country-pop guitarist and comedian Jim Stafford played one on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, partly for comic effect.

In due course, Roland figured out that a separate hex pickup and control bundle that could be attached to virtually any existing electric guitar was the way to go, and the company has rolled through an impressive range of synth units ever since.

The quirkiness and bygone-cutting-edge charm of these early units still has a great appeal for many players today, though, and GR synths from Roland’s first decade of the venture have attained a certain collectability on the 21st century market.

That, and any and all of them can be surprisingly versatile creative tools.

For information on Roland's latest Boss guitar synthesizer gear click here.

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.