“Took it home, plugged it in, and immediately the entire room started to vibrate. I went, ‘Holy s***!’” Neil Young on his Old Black Les Paul and the amp that's been his go-to for nearly 60 years

The guitarist shared deep details on his Les Paul, Fender Deluxe and Whizzer controller in a classic interview from our archive

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

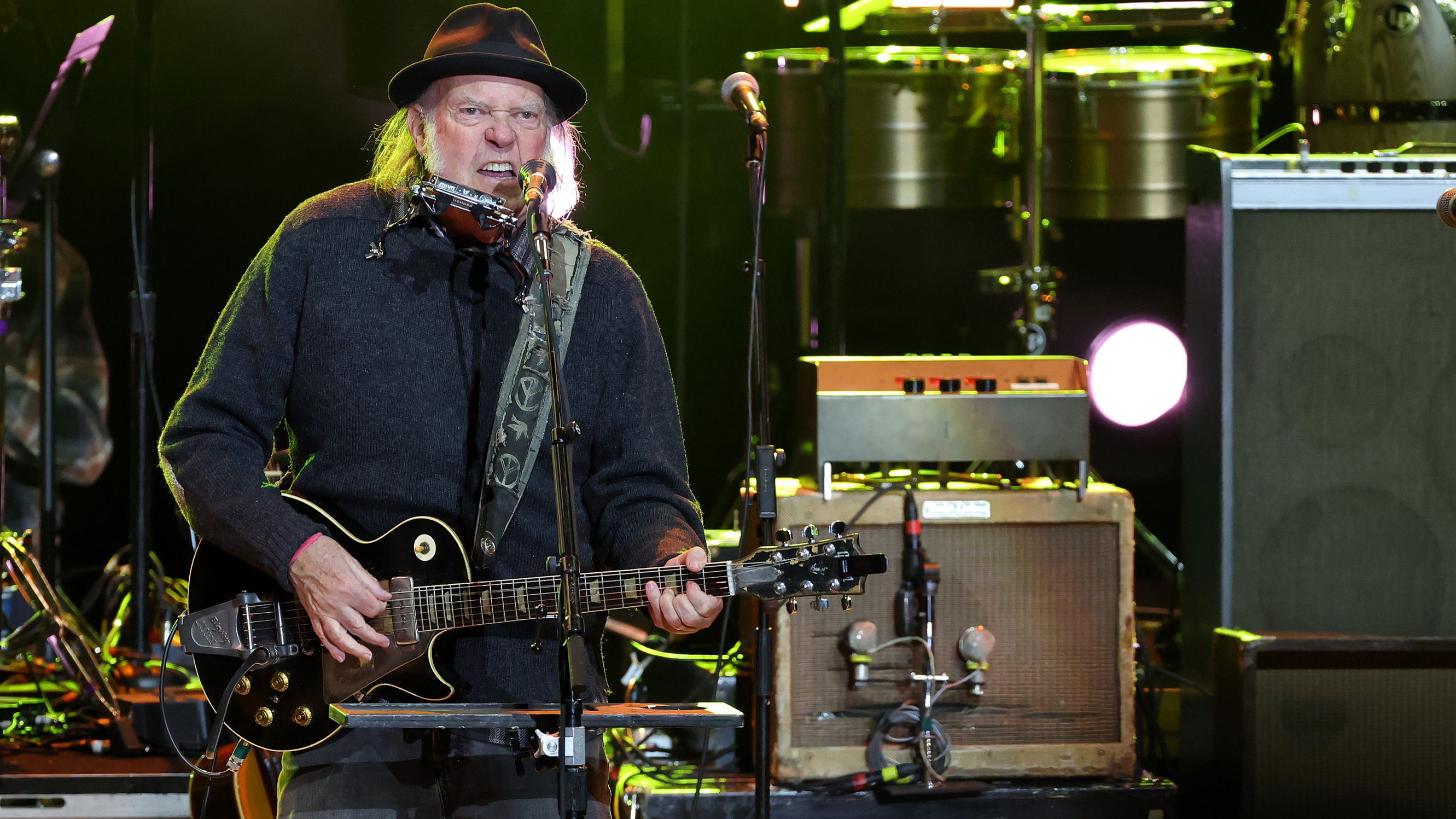

For close to 60 years, the heart of Neil Young’s live rig has been a very specific tweed 1959 Fender Deluxe that he controls remotely with a bespoke device called the Whizzer, which physically turns the amp's knobs when Young hits one of the foot switches on a red box onstage.

The amp itself is a four-input 1959 tweed Fender Deluxe 5E3, a 15-watter with just two volume knobs and one tone control. Young’s Deluxe is completely stock if you ignore that he’s had to replace its two 6L6 tubes. The new tubes increased the amp’s output from 15 to 19 watts after it was rebiased, causing it to run hot. In a March 1992 column for Guitar Player, Young’s guitar and amp tech Larry Cragg said he has “fans pumping a lot of air into the back of the Deluxe” since they swapped out the old tubes.

As for the Whizzer, Young came up with the idea for it in the 1970s, and his amp tech Sal Trentino made the first, a two-preset unit Young began using in 1978 on Rust Never Sleeps. His tech Rick Davis made the four-preset Whizzer in 1991.

“Its got four presets that completely control the three knobs on the top of the amp,” Craig told us. “He locks in the preset he wants, and it will always go back to that particular spot. We find that when you have the volume and tone all the way up, by turning that second volume knob up to about 10, it starts to fade away. But right before it starts to fade away, something else happens, and that has to be in exactly the right position. You can't breathe on it, or it fucks it all up.”

Young himself detailed the subtleties of the ’59 Deluxe in that same issue, in an interview with Jas Obrecht, to coincide with the release of his live album Weld.

“That's how I get the guitar sounds to change subtly,” he said of the Whizzer. “The Deluxe goes up to 12 — not 11 — and with everything floored, if you back it down to 10 and half from 12, all of a sudden it's chunky sounding on the attack. If you have it up on 12, then it just saturates completely and opens up after the attack. But if you back it down, it'll catch the attack.

“So I've got one button just to change that one thing that much.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Young offered an example of how he uses Whizzer with his Fender Deluxe.

“On a Fender Deluxe, there's tone and two volumes,” he explains. “The volume on the channel you're not using will affect the volume of the channel you are using, even when you're not plugged into it, because of the drain on the power amp. Having the ability to bring up the channel I'm not even using — so the overload thing comes on — or to change the treble here and there, those are the things I couldn't have done without this technology. Technology hasn't affected the sound, only the control of the sound.”

And when it comes to distortion, Young said it comes entirely from volume.

“There is no amp gain. We don't use a distorted effect at all. Just the Fender Deluxe.”

I couldn't go without it. There is no spare. I've got 10 spares, but none of them sound like it.”

— Neil Young

While some professionals might be inclined to leave a precious vintage amp at home when they tour, Young said the Deluxe is vital to his sound. When he hits the road, it goes with him.

“I couldn't go without it,” he said. “There is no spare. I've got 10 spares, but none of them sound like it.”

He pointed out that each amp performed differently as there were fewer standards in place for components in the early days of electronics.

“All Fender amps are different, made with different amounts of metal and windings, all these things,” Young said. “The transformers are all different powered. Everything used to be loose, y'know, so every combination of specs was different.”

He recalls exactly when and where this particular Deluxe came into his life.

“I got mine for $50 at Saul Bettman's Music on Larchmont in L.A. in 1967. Took it home, plugged in this Gretsch guitar, and immediately the entire room started to vibrate.

“The guitar started vibrating, and I went, ‘Holy shit!’ I turned it halfway down before it stopped feeding back.”

By the early 1990s, Young had added a small arsenal of pedals to his setup, giving him new ways to mess with his sound.

“I do a lot of things to make the sound more distorted, like by introducing an octave divider in conjunction with an analog delay, which is before the octave divider,” he said. “The routing of these things is really important — what hits first and then gets hit by something else.

"I have a line of six effects, and I can bypass them completely or dip in and grab one without going through the one in front of it. Or I can use all six of 'em or any combination that I want. I set them up in any order so that they affect each other in a certain way, and that's how I get my sound.”

Young explained that he triggers the pedals himself. “I can't imagine anyone operating it for me offstage,” he deadpanned. “No, they'd be dead.

Among the pedals were “a digital echo that I use because it has a particular gated-echo sound. When I tried it out at the Guitar Center in Hollywood, the salesmen were demo-ing all these sounds like on a Phil Collins record or the background of a Cyndi Lauper record.

"I said, ‘Let me try it for a minute,’ turned everything all the way up, except for the mix [control], and then I started playing the guitar really staccato.

“I turned the mix up and got ‘whop, whop, whop, whop,’ like this giant popcorn machine exploding kind of a sound. I like that sound, so I use it as an effect. When I've gone just about as far as I can go, I stick that on it and just hit harmonics and choke them. It splats out all this ridiculous noise all over everything. But I don't use it in a real sense to get a sound that it was meant to get.”

No, we do it. We just put a hole in the stage. There's always a way."

— Neil Young

His most commonly used effects, he said, were “an original tube Echoplex, an MXR analog delay, a Boss flanger, and an old white Fender reverb unit with new springs that are separate. The springs are on a microphone stand that goes on the cement floor of the building. It extends up to the bottom of the stage, and the spring stands on top of the microphone stand and the wire comes through a hole in the stage completely separate.

“I can't use it if I don't do that, because if I jump onstage, the spring rattles. It has to be isolated from the surface of anything that's vibrating.”

And what if the venue won’t allow Neil Young to drill a hole in its stage?

“No, we do it. We just put a hole in the stage,” Young insisted. “There's always a way.

"It can't be very far away, because with a long wire, you lose the fidelity, the high end where the reverb lives, so the magic is gone. You've got to keep it close and really short.”

As for guitars, Young said. “I buy guitars mainly to remember something by. If I'm enjoying a place, I will try to find an old guitar in that area, and that will always remind me of when I was there. The way it sounds is the way I sounded when I was there.

“I’ve written a lot of songs on a Martin D-18 that I really like, and I stole that out of [manager] Elliot Roberts' office. I always think of Elliot's office whenever I play it.

“And there are other reasons to buy guitars. You can buy them because they're classics. I collect 'em, so I'll buy an Explorer or a Flying V or a Black Falcon or a White Falcon just because that's what it is. But I got those now, so I don't need those anymore. Material things are becoming less and less relevant to me, so I'm not contingent to buy guitars.”

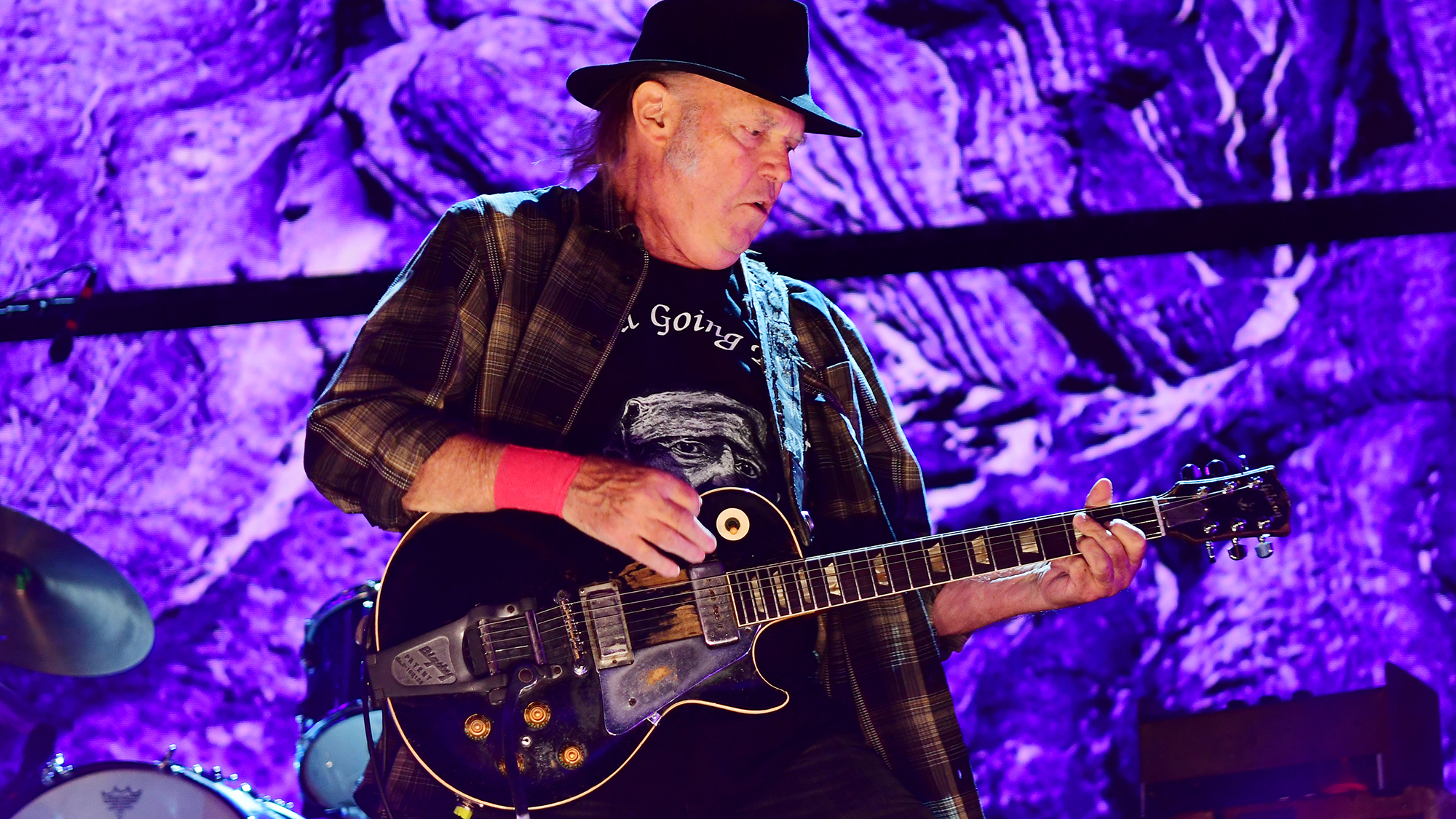

Old Black, Young's modified 1953 Gibson Les Paul, is famous for having the mini-humbucker from a 1972 Gibson Firebird, rehoused in aluminium, in its bridge position. As Young explained to Guitar Player, the original pickup went missing after he dropped it off at a store for repair when it developed a bad hum.

“I went back to get it, and the store was closed and everything was gone,” he said. “I never got the pickup back, so now there have been two or three pickups in place of the original. I guess I used the Firebird pickup on all the things I played on my black guitar since 1973.”

I went back to get it, and the store was closed and everything was gone. I never got the pickup back."

— Neil Young

One other constant is the addition of a Bigsby whammy bar. Young has had no interest in more modern accessories.

“It works; it's expressive,” Young said of the Bigsby. “The wang bars they have now are not expressive; they're too tight. You can go way down and come way back up and do these metal licks and still stay in tune. Big deal — stay in tune, great. You already were in tune. I go out of tune in every song, because the thing just doesn't stay in tune.

“But when you keep moving, you never know when you're in tune. It's like hand-controlled flanging. And if you have a tape repeat on, an Echoplex, and you just ever so slightly use the Bigsby, then your sound is going up and down, but the echo is always following behind it. So it's like you really have two guitars that are not only on two different attacks, but one's in a different pitch. It's a huge sound.

“I’ve got the Bigsby worn into my hand. I can't do anything else. It has to be a Bigsby.”

Jas Obrecht was a staff editor for Guitar Player, 1978-1998. The author of several books, he runs the Talking Guitar YouTube channel and online magazine at jasobrecht.substack.com.

- Christopher ScapellitiGuitarPlayer.com editor-in-chief