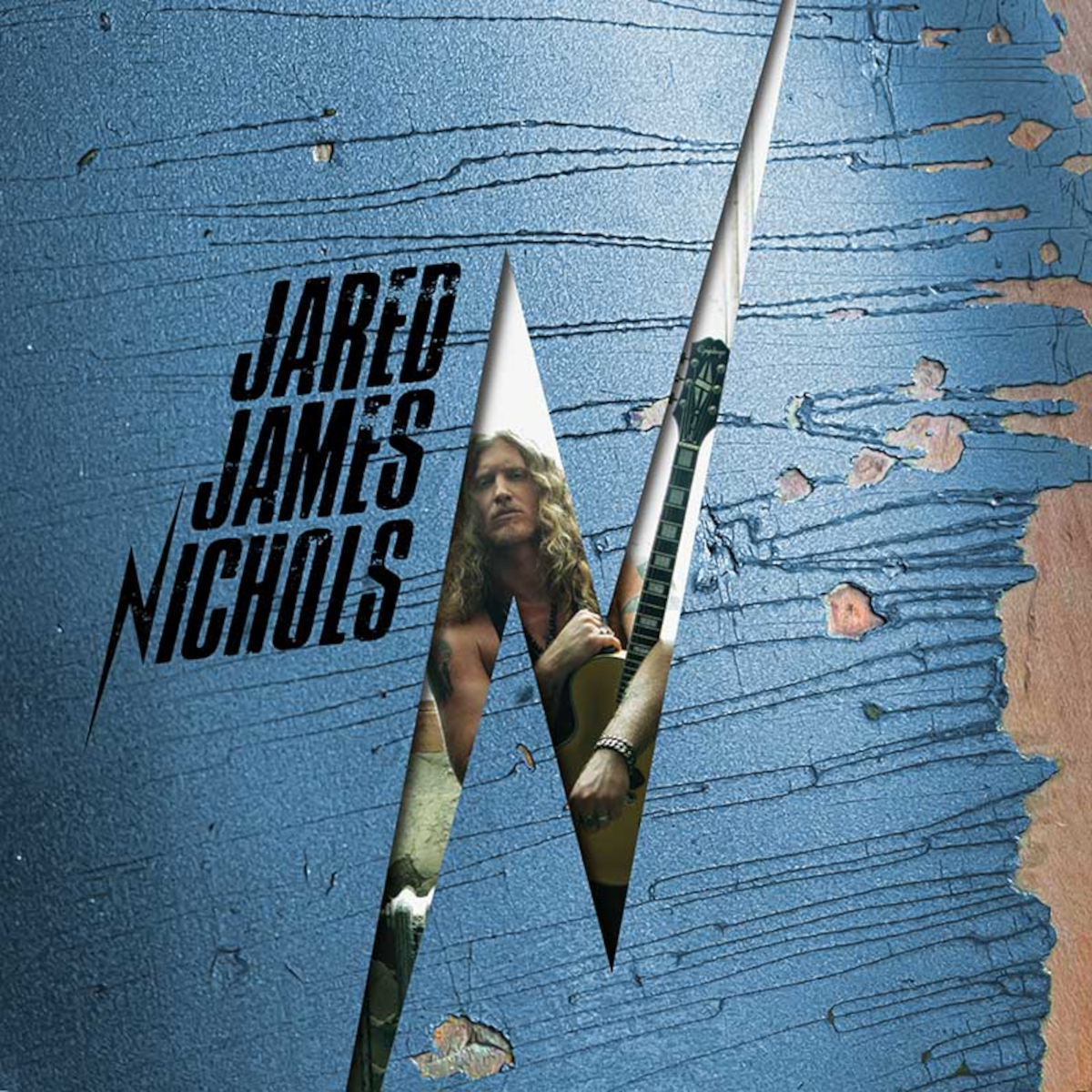

“With the Best Record I’ve Ever Made, I’m Filled With Nothing but Gratitude”: Jared James Nichols Is Mighty Stoked About His New, Self-Titled Album

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jared James Nichols is mighty stoked about his new, self-titled album, but truth be told, he’s thrilled that he was able to make a record at all.

In October 2021, a few months before hitting the studio, he broke his right arm when he picked up a road case the wrong way and his arm twisted under the stress. The accident required surgery and left him with a metal plate and 16 screws in his arm – and not a lot of assurance from doctors that he’d be able to play guitar again.

“It was every guitar player’s nightmare,” Nichols says, “but I was determined that nothing would stop me. I said, ‘Give me my guitar. I’ll work it out.’ It took some time, but I came through it. To be here playing better than ever, and with the best record I’ve ever made, I’m filled with nothing but gratitude.”

The last thing I want to do is play the same old licks you’ve heard time and again

Jared James Nichols

Nichols’ assessment of his third album is no cavalier boast. The 12-cut record, recorded live to tape, is an absolute smoker that should come with a warning: “Not for the Faint of Heart.” There’s gonzo blues blasters (“My Delusion,” “Hard Wired”), Sabbath-inspired Earth movers (“Hallelujah,” “Easy Come, Easy Go”) and action-packed updates on grunge (“Skin ‘n Bone,” “Down the Drain”). And that’s just half of it.

A fingerstyle guitarist with a pummeling approach that’s more Johnny Ramone than, say, Segovia, Nichols distinguishes himself through the set as a font of creativity: Every time you think one of his fiery riffs is going to zig, it zags.

“The last thing I want to do is play the same old licks you’ve heard time and again,” he says. “Too many guys get stuck in a rut with riffs because they aren’t serving the song. Each song said something new, and my attitude was, Okay, let’s see where this thing takes me. And every time, it surprised me.”

Where did the whole playing without a pick thing come from?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I’m a lefty. When I started on guitar, I held a righty guitar upside down, and I was like, “Oh, this is cool.” My first guitar teacher told me to flip the guitar over, and he put a pick in my hand. I tried to get with it, but my motor skills in my picking hand just weren’t there. My hand felt flimsy. But whenever I used my fingers, I felt really connected to the strings.

Fingerstyle opened up a new universe for me

Jared James Nichols

Everybody told me, “Don’t do that,” but I went for it. Then I saw videos of Jeff Beck and Mark Knopfler, and there was Derek Trucks and Albert King. I said, “All these cool guys can do it, so I can, too. I went at it 12 hours a day.

I imagine it was hard on your picking hand.

Oh yeah. There were a lot of trials and tribulations. I tried using my nails, and that didn’t work. I remember playing a gig where I ripped my thumbnail clean off. It was horrible. So I went from using my nails to going flesh on strings.

Over time, I was able to play more aggressively because I now had the world’s fattest guitar picks. I can do so much with my fingers – not just single-note stuff but I can play riffs with drones underneath. Fingerstyle opened up a new universe for me.

Your stylistic approach is interesting. There is blues, but there’s also classic rock and a definite grunge influence.

Yeah, people think I’m going to be straight blues, but I grew up in the 2000s, so the first bands I heard were Soundgarden, Nirvana, Alice in Chains, Van Halen – stuff like that. Through my parents, I heard Patsy Cline and Santo & Johnny, and I loved them.

I love all the freedom I have with the trio

Jared James Nichols

Once I found classic rock, I was playing guitar and learning riffs, so I wanted to know where Zeppelin and the Who got their stuff from. That led me to the blues: “Oh, Jimi Hendrix was into Buddy Guy? Clapton was into Hubert Sumlin and Otis Rush?” Jerry Cantrell’s “Man in a Box” is really a souped-up blues riff.

You lead a pretty classic power trio. Did you ever work with a second guitarist?

I tried, because when I started the trio I realized how much space I had to fill. But whenever I tried bringing in another guitar player, I would just play on top of them. It was a guitar fight.

Then I started touring, and it just made more sense to streamline everything. I found my way as a singer who plays guitar. Now I love all the freedom I have with the trio.

Like your last album, you recorded this record live and loud in the studio.

Sure did, and I have to credit Eddie Spear, my producer, for going with that. We have the same brain. Instead of, “We’d better turn this down,” he’s like, “Let’s see how far we can push this till something blows up.” [laughs] So we cut the tracks live and loud, with minimal overdubs. I’m singing as we play.

We cut the tracks live and loud, with minimal overdubs. I’m singing as we play

Jared James Nichols

The only thing that flipped me out at first was when he said, “Oh, by the way, I love to cut to tape.” Right away, I got nervous because that meant the band had to be right on the money. Every lick, every solo – every everything had to be well rehearsed.

The solo in “Easy Come, Easy Go” is insane. What’s going on there?

That was a happy accident. I was doing this descending riff on a ’56 Les Paul Junior, and I went right up to the amp and started doing this feedback loop. The pickups went wild, so I worked with it. It kept building and building.

I wasn’t going to play the solo that way, but it just happened. So that was an instance where we were totally rehearsed, but everything turned in a positive way.

Does that happen a lot, where you just lose yourself while soloing?

Absolutely. Like in “Hallelujah” – I don’t even remember cutting it. That’s what happens – I do lose myself. I used to get scared about that, but with this record, I listen back to the solos and I think, What was I doing? Why did I do this? But then I think, Well, it sounds cool, so I must have been inspired at that moment.

I could mention a lot of songs, but there’s one in particular, “Good Time Girl,” that really shows off your vibrato.

I love to play hot-shit fast guitar, but when I can hit one note and make the guitar cry, it shakes me to my core

Jared James Nichols

Thanks. I’ve always been obsessed with bending and vibrato. There’s that saying: “You can identify a guitarist with just one note.” That’s what I aspire to. I love to play hot-shit fast guitar, but when I can hit one note and make the guitar cry, it shakes me to my core.

You mentioned a ’56 Les Paul Junior. Was your “Old Glory” Les Paul one of the main guitars on the record?

“Old Glory” was the go-to. Nothing besides P-90s were harmed during the making of this record. [laughs] I had “Old Glory” and my “Ole Red” Les Paul, which is a 1953 with soapbars. I also had my newly acquired ’52 Les Paul that had to be restored after it was practically destroyed in a tornado. I think those were the main ones.

And, of course, you recently came out with your own “Old Glory” and “Gold Glory” signature models from Epiphone.

Yeah, man. My mind is still blown about them. Like I said, I’m just a grateful guy at this point. If I have any advice for people, it’s to do what you love and believe in yourself. And I don’t say that in a cheesy way. It’s all true.

Order Jared James Nichols' self-titled album here.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.