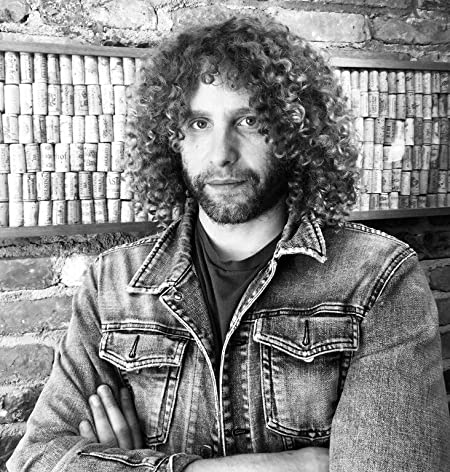

“People Talk About the Good Old Days, but the Good Days Are Today”: Television Guitarist Richard Lloyd Reflects on His Highly Influential Career in Music

The most galvanizing guitarist to emerge from New York’s CBGB scene recalls a lifetime of nerve-tingling axe work

***The following interview extract originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Guitar Player***

When Guitar Player catches up with Richard Lloyd at his home in Chattanooga, Tennessee, it’s early in the afternoon on what is shaping up to be a pretty good day.

“Later on, I’m going out with my wife to eat sweet potatoes,” the guitarist reports. “And then I’m going to see Alice Cooper tonight.”

Lloyd even manages to find a silver lining in the fact that his car just broke down. “I had to replace the battery, but I needed a new battery anyway,” he says. “So it’s good and good.”

Car troubles aside, Lloyd has every reason to be happy these days. Several decades into his career, he remains a hero to generations of outsider guitarists who had their musical senses ignited by his seminal work in the ’70s with Television, or perhaps by his playing in the early ’90s with Matthew Sweet or his solo output that began with 1979’s Alchemy.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

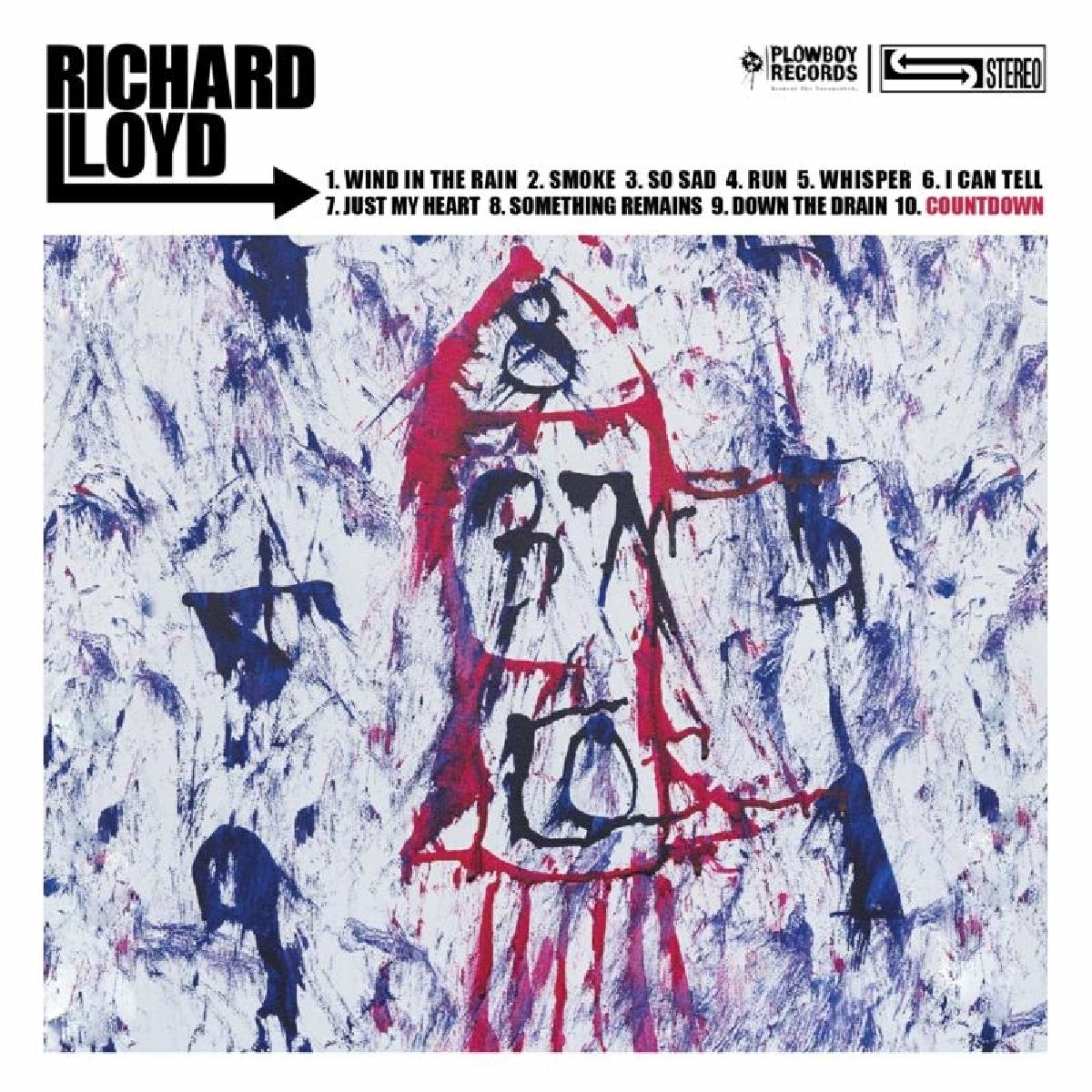

His latest solo album is titled The Countdown. The 10-song effort finds Lloyd singing and playing guitar with as much fire and urgency as ever on a collection of sharp, snappy tunes that fuse punk energy with pop, rock, soul and jazz sensibilities.

It’s all accented by his trademark jagged, exploratory guitar work, high-tension licks and hot-wire soloing – or as he calls it, “fragmented spits of notes.”

Take, for example, the album’s title track, which ends The Countdown in a swirl of burbling organ, squalling guitars and buzzing feedback.

“It was this idea I had of space flight,” Lloyd explains. “I had the opening riff and then the rhythm part, and the vocal was all off the cuff. It’s kind of a jam. I loved doing it.”

One of his favorite things about the track is that it reaches back, almost full circle, to his earliest experiences with the guitar.

“There’s a track on that song that’s all feedback,” Lloyd explains. “And that was what I would do when I first started playing guitar as a teenager. Back then, I didn’t know how to move my left hand on the neck. So I just used the tremolo bar to make airplane and motorcycle sounds for the first couple of weeks, until I could get my hand to play the barest part of a chord. I wasn’t actually playing with my fingers as much as I was playing with the electricity.”

A voice came to me in an audio hallucination, you might say. And it said, ‘You must play a melody instrument’

Richard Lloyd

For Lloyd, discussions about music often have a dynamic element to them, with energy either harnessed or reacted to instinctively, and sometimes in an almost supernatural way. This sensibility is evident even in his explanation for why he picked up the guitar after initially cutting his teeth as a drummer.

“I was playing drums one day,” explains Lloyd, who was born in Pittsburgh but moved to Greenwich Village in lower Manhattan while in grade school, “and all the color went out of me. It was like The Wizard of Oz, where Kansas is in black and white and Oz is in color.

“All of a sudden I was in Kansas. And then a voice came to me in an audio hallucination, you might say. And it said, ‘You must play a melody instrument.’ And the guitar was my choice out of those possibilities. Because I didn’t want to play the damn violin.”

What happened to Lloyd once he started playing the guitar is a story that has now become the stuff of legend.

He befriended a kid from Brooklyn named Velvert Turner, who was not only a fellow budding guitar player but also happened to be a protégé of Jimi Hendrix.

[Jimi Hendrix] smacked me in the face, the stomach and the face again. I thought to myself, He punches a pretty good punch

Richard Lloyd

“According to Velvert’s mother,” Lloyd recalls, “he was standing in front of the television one day and saw Jimi performing. And he started jumping up and down saying, ‘I have to meet that guy!’ And apparently he sought out Jimi, and Jimi took Velvert under his wing as, like, his little brother.”

Lloyd pauses.

“I mean, that’s the story I’ve heard. And knowing Velvert, who passed on in 2000, I believe it. Because he was a wacky kinda guy. A magical-thinking kind of fellow. I was, too. I am, still.”

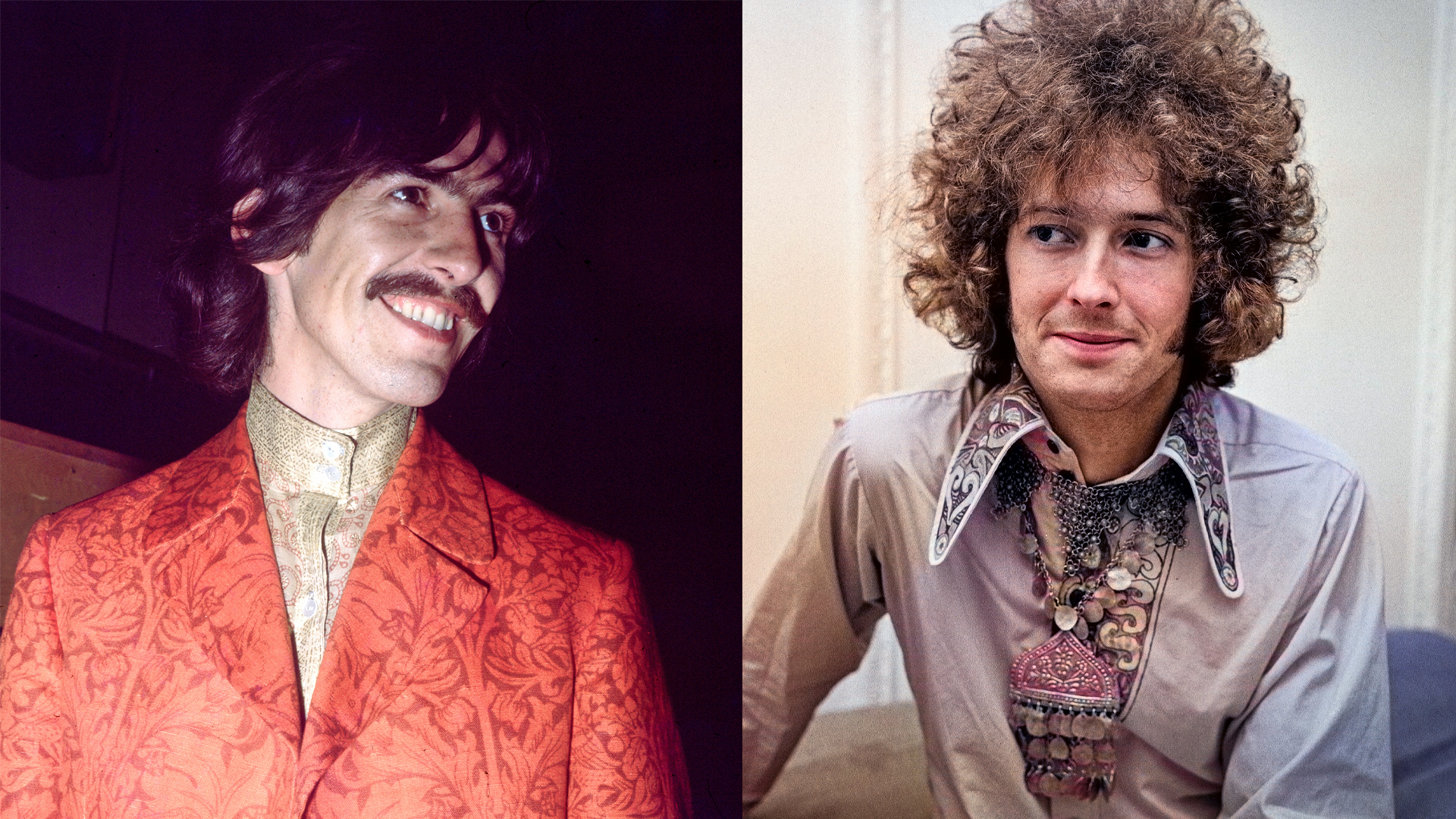

Hendrix gave guitar lessons to Velvert, who in turn would show his friend Richard everything he had learned, in effect making Lloyd a once-removed student of Jimi’s.

Through Velvert, Lloyd also got to see Hendrix perform several times in New York City – “In my mind it was like looking into a nuclear reactor,” he says about watching Jimi perform – and spent time with Jimi in recording studios.

Lloyd also has an oft-told story about unintentionally insulting Hendrix one night at a gig billed as the Black Roman Orgy, at which point the guitar god “smacked me in the face, the stomach and the face again.

“I thought to myself, He punches a pretty good punch for a scrawny black guy,” Lloyd recalls. (His other thought: “How can I absorb this energy?”)

Hendrix was far from the young Lloyd’s only brush with guitar greatness. For instance, there was the time in the early ’70s when he wound up performing onstage in Boston with John Lee Hooker.

“I just walked into the dressing room and sat myself down. You could do that back then, if you had the cojones,” Lloyd says. “And John Lee Hooker called over to me and he said, ‘What do you do?’ I said, ‘Well, I play guitar.’ He told me, ‘I’m going to invite you up onstage, and you better get up there, because if you don’t, I’ll have to turn the lights on and chase you down.’”

[John Lee Hooker] told me, ‘I’m going to invite you up onstage, and you better get up there, because if you don’t, I’ll have to turn the lights on and chase you down'

Richard Lloyd

About three-quarters of the way through that night’s show, Lloyd recalls, “I heard him announce, ‘I’m going to invite up a new guitar player. Let’s have a warm hand for Richie Lloyd!’ He called me Richie, which nobody else did. But he certainly could.”

As for any advice Hooker had for the young guitarist? “He told me to take all the strings but one off my guitar, and learn that one string up and down the fretboard. And then after I did that, to add a second string, and so on. Basically, he taught what I call ‘vertical knowledge.’ And it was great advice.

“Of course,” Lloyd adds, “I couldn’t afford a set of strings. So I didn’t do it.”

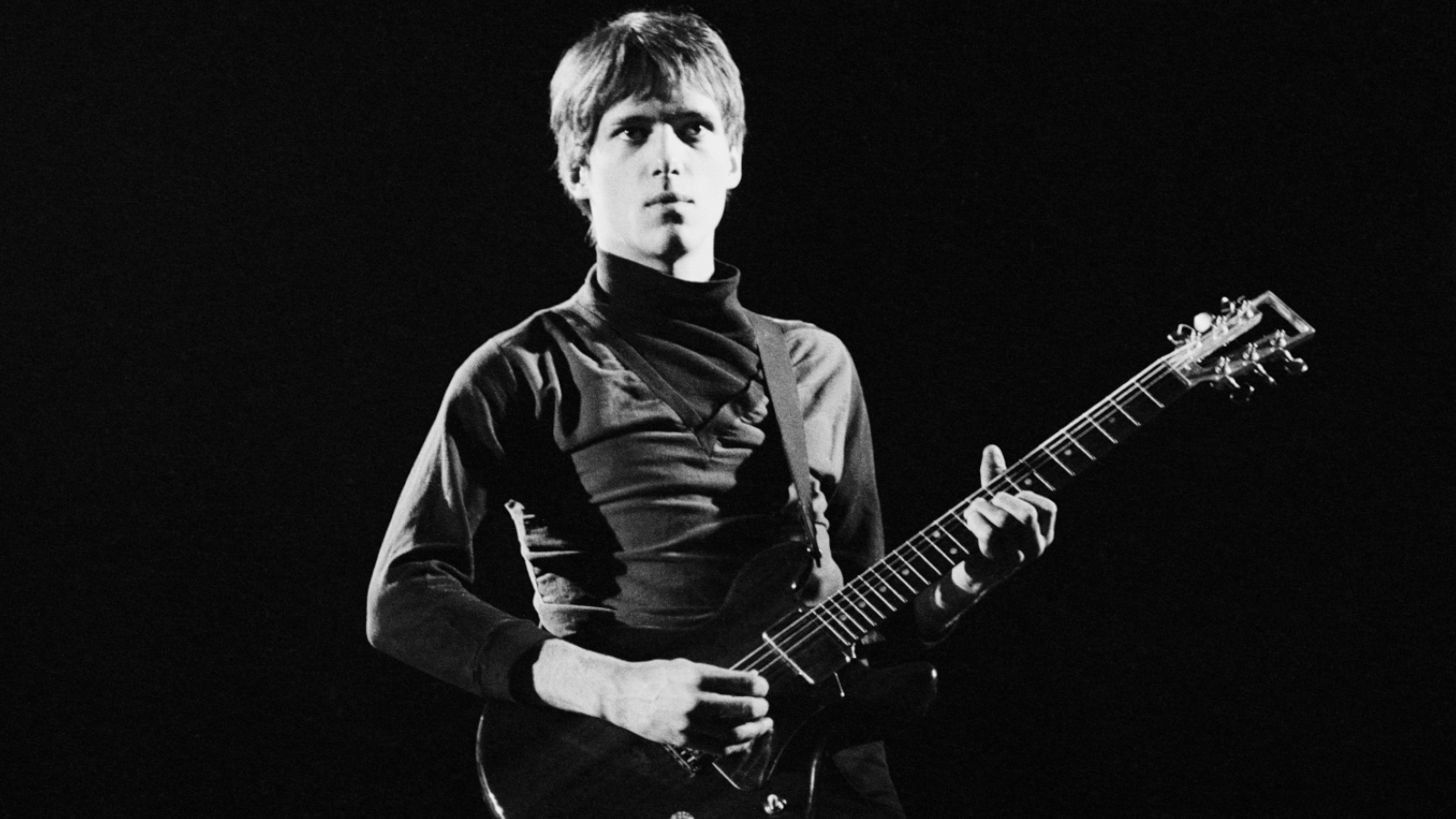

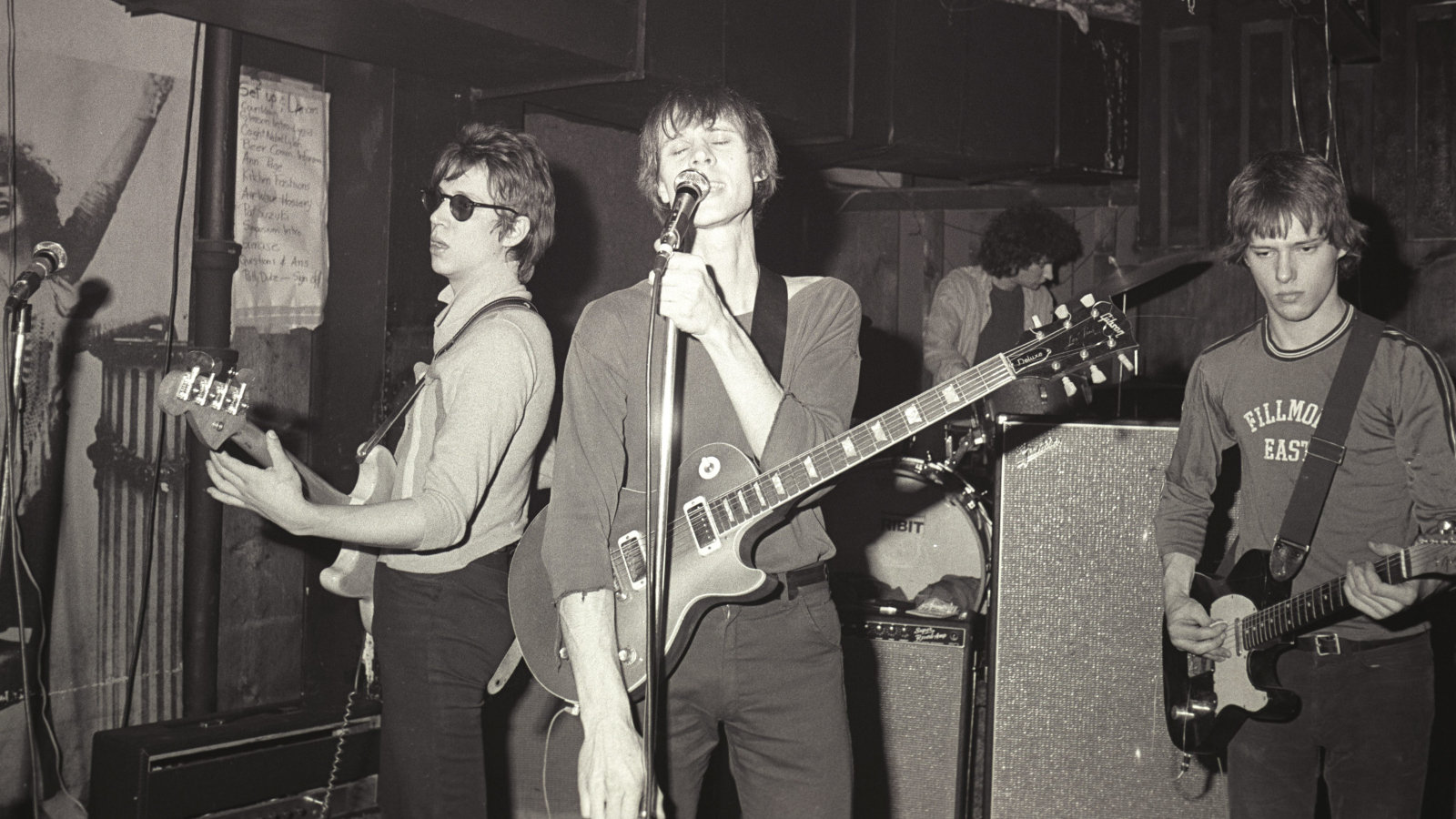

For all of Lloyd’s proclamations of elbow rubbing with legends like Hendrix and Hooker, what is perhaps most remarkable about his guitar playing is that when he emerged with Television, his first true band, he exhibited a style that seemed almost completely untethered to traditional rock or blues idioms.

Rather, together with singer and guitarist Tom Verlaine, Lloyd created one of the most unique and forward-thinking guitar albums of the ’70s or any era: Television’s 1977 debut, Marquee Moon.

And while the band is commonly lumped in with the New York City punk scene (and was the first rock group to perform at CBGB, paving the way for the Ramones and others), Lloyd never saw Television as being so easily classifiable.

Ahmet Ertegun said, ‘I can’t sign them to Atlantic because this is not earth music'

Richard Lloyd

“We were once called ‘four guys with a passion’ by the director of Rebel Without a Cause,” he says, referring to Nicholas Ray, who helmed the 1955 teenage drama. “I thought that was pretty good.

“And I remember [Atlantic Records co-founder and president] Ahmet Ertegun said, ‘I can’t sign them to Atlantic because this is not earth music.’ I love that line – although I was going to the bathroom when he said it to [legendary producer] Jerry Wexler.”

Television only lasted through one more album, 1978’s Adventure, before splitting. Afterward, Lloyd embarked on a solo career that, despite strong showings like 1986’s Field of Fire, never seemed to truly take off.

In the early ’90s, he and Verlaine restarted Television, and he recorded and toured off and on with the band until exiting in 2007.

His only true intersection with the mainstream music world came via his association with alt-rocker Matthew Sweet, and in particular the jagged, skronky guitar lines (“someone once likened it to Coltrane, like shards of glass,” he says) that Lloyd added to the musician’s power-pop albums Girlfriend and Altered Beast.

It’s almost like I’m not playing. The electricity is playing me

Richard Lloyd

As for what a guy like Sweet saw in a player like Lloyd? “I wish I knew,” Lloyd says. “I mean, I guess it’s that thing about a high-octane sort of guitar ace who comes in and…”

Lloyd trails off and starts again.

“I always go in and say, ‘I’m probably going to capsize this song,’ you know? I remember with Matthew, I would play something and then everyone [in the studio] would go, ‘Okay, we’re finished.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, that was full of mistakes.’ And Matthew would tell me, ‘Your mistakes are better than most people’s good stuff!’”

Lloyd pauses, and then returns to a common theme.

“It’s a certain energy I have, I guess. And when that energy gets loose, I’m just sitting back and watching. It’s almost like I’m not playing. The electricity is playing me.”

That energy is all over The Countdown, from the curlicue (and admittedly “Marquee Moon”-like) licks that kick off the opening track, “Wind in the Rain,” to the jaunty single-note runs in “Whisper” to the squalling lead lines in “Down the Drain.”

Lloyd says he and his band recorded quickly in the studio, and he kept his gear likewise streamlined.

When I’m playing music, I see a lot of color tones, blues and reds and greens, and when I’m painting it’s a very musical experience

Richard Lloyd

His main guitars were a Supro Black Holiday, a Vintage Guitars Strat-style model and an Epiphone Casino, which he plugged into a Vox AC30 and a Supro Black Magick.

Pedals were minimal as well – an Echoplex, an “old Boss overdrive,” an MXR Carbon Copy and a DigiTech FreqOut, which, Lloyd says, “is essentially a feedback machine. I used that specifically on the song ‘The Countdown,’ because you can be at a low volume and still get good feedback. I didn’t have to turn the amps on 10 and be in a room with earplugs and, uh, you know, flying saucers.”

In addition to writing, recording and singing the material on The Countdown, Lloyd also created the artwork that adorns its cover.

“I’ve been painting for about three years now,” he says. “I suffer – or maybe I’m blessed – with synesthesia, where one sense blends into another. So when I’m playing music, I see a lot of color tones, blues and reds and greens, and when I’m painting it’s a very musical experience.

“The auditory realm and the visual realm are both very, very strong in human beings. So I like to delve into both of them.”

Lloyd hasn’t been one to live in the past. After nearly a lifetime of residing in New York City, he left for Chattanooga almost three years ago.

“My wife’s parents are here,” he explains. “And when we were looking for a new apartment in New York, we were finding things that were a third of the space for the same price, so we said ‘to hell with this.’”

Meanwhile, despite his newfound affection for painting, the guitar remains his first love, and he’s still a student of his craft.

The original impulse that drove me to play music has not dissipated at all

Richard Lloyd

“I’m practicing an awful lot now, trying to get good,” Lloyd says. “I mean, Segovia, a great classical guitarist, was asked when he was 70 or something, ‘Now that you’re a master of the guitar…’ And he went, ‘No, no, no. The guitar is the master. I’m just the student.’ You can never get to the bottom of what the guitar can do.”

Lloyd continues.

“The original impulse that drove me to play music has not dissipated at all. It’s sort of like a pool ball getting hit. It continues to roll until it hits something else, and then that ball keeps going.

“I’m still in motion from those original impressions that I got from listening to AM radio when I was nine and 10 years old.”

What is comes down to is that, even with his unusually colorful past, Lloyd is still very much living in the present.

“People talk about the good old days, but the good days are today,” he says. “And in a year or two they’ll be the good old days. But right now are the good days. I totally believe that. I wake up happy and I go to sleep happy. And in between, you know, I’m pretty okay.”

Order The Countdown by Richard Lloyd here.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.