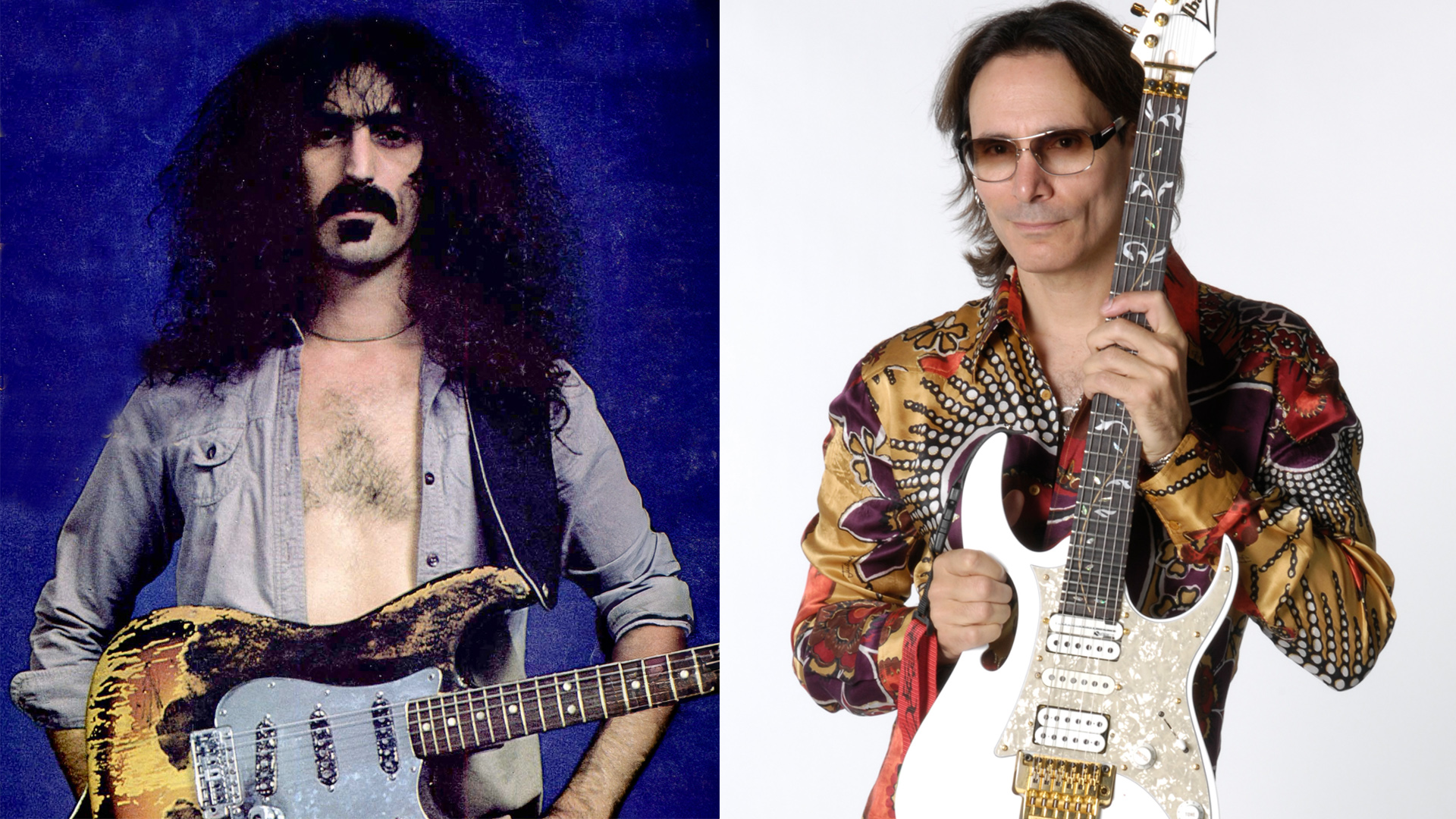

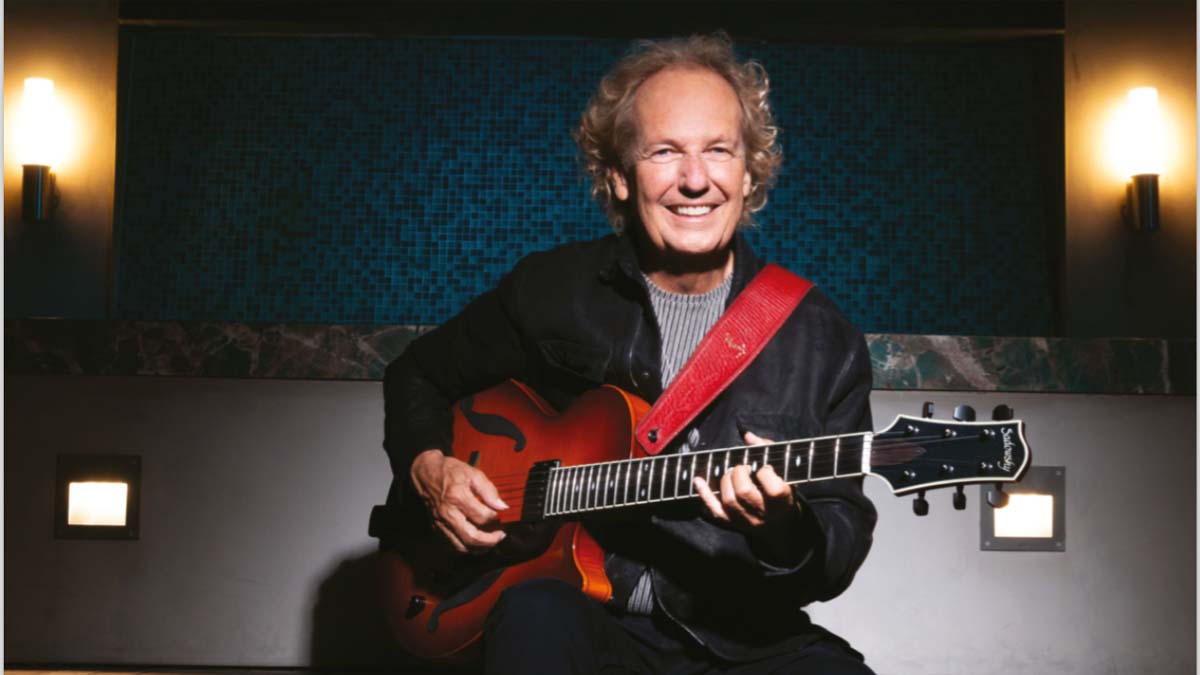

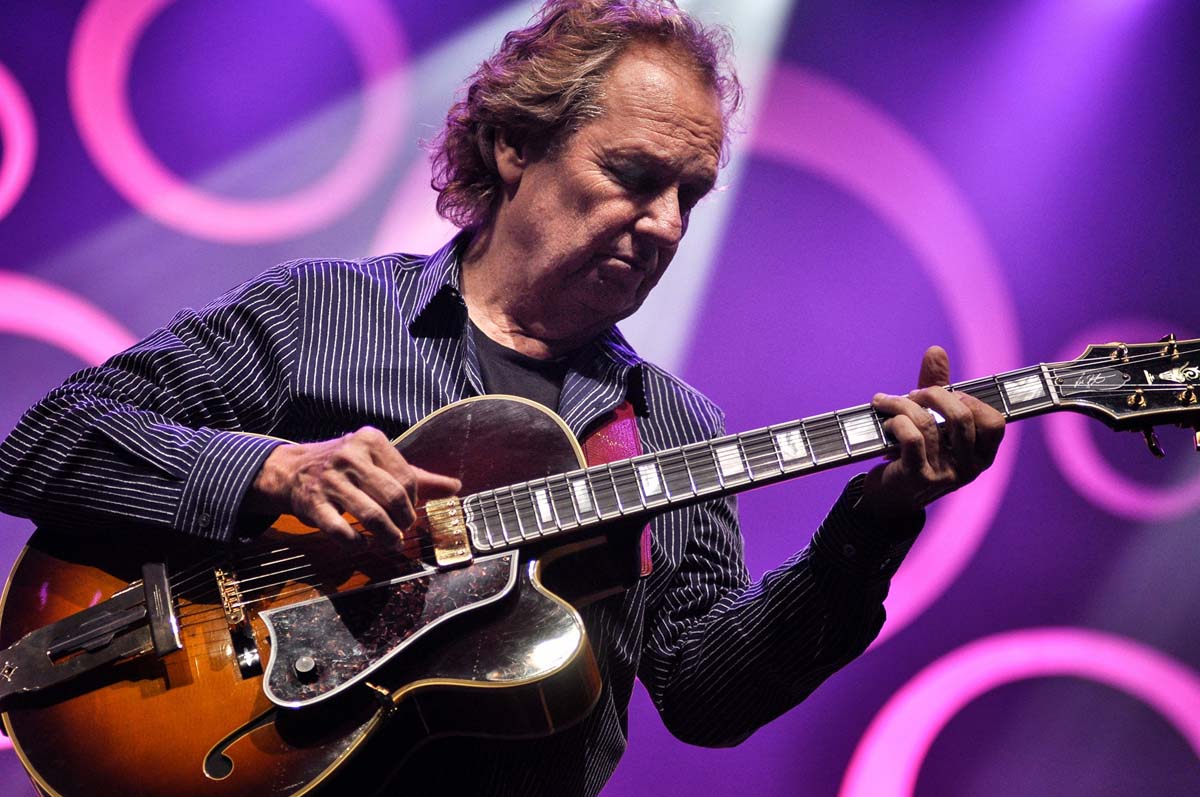

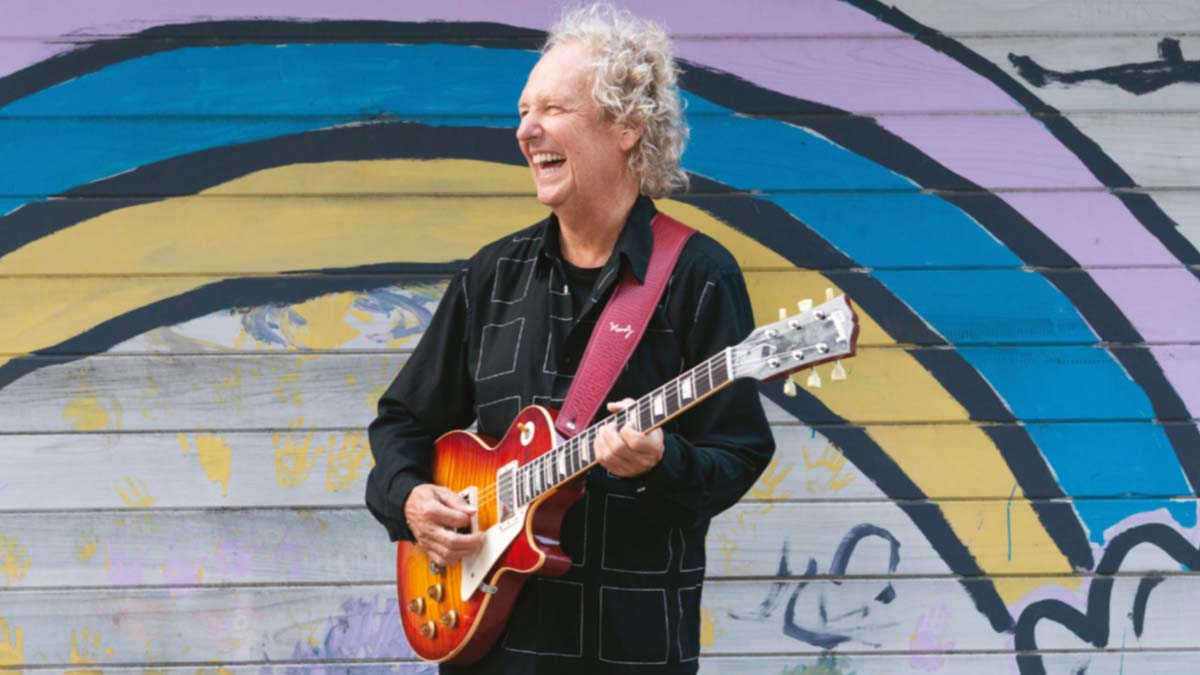

Lee Ritenour on Completing the Most Cathartic of Comebacks with His Breathtaking New Album, ’Dreamcatcher’

First came the house fire. Then heart surgery. Now Ritenour bounces back with his first ever solo guitar record.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In a career that has spanned more than 50 years, Lee Ritenour has played on tracks recorded by some of music’s biggest names. Aretha Franklin, Joe Henderson, Quincy Jones, Dizzy Gillespie, B.B. King, David “Fathead” Newman, George Benson, Pink Floyd – those are just some of the artists Ritenour has worked with.

Along the way, he launched his own solo career in 1976 with the album First Course, performed as a member of Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra, and recorded three chart-topping albums with the smooth-jazz group Fourplay. He’s also become known for playing a red dot-neck Gibson ES-335 that he’s used throughout his career.

Growing up in L.A. in the 1960s, Ritenour began playing guitar at age eight, and by about the age of 15 had cut what he calls his “first big one,” a demo session with the Mamas and the Papas.

By his own estimation Ritenour has recorded approximately 45 albums, yet until the release of his new record, Dreamcatcher (Mascot Label Group), he had never recorded a true solo album, one created without input from other musicians or producers.

Made at his home studio in Marina del Rey, California, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Dreamcatcher finds him, for once, flying on his own. “People have been telling me for years, ‘Rit, you gotta make a solo guitar record,’” he relates.

“In the past, I’ve always been the band guy, the ensemble guy, the collaborative-guitar-player guy. So this was the one project I hadn’t done. And this year, I knew it was time.”

It certainly was. Covid-19 wasn’t the only thing the 69-year-old has had to deal with. In 2018, the house and studio he and his wife owned in Malibu burnt down in one of the fires that has ravaged California.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“About 100 of my guitars went up in the fire, plus 40 amps, lots of music, the history of my whole career, pretty much,” Ritenour says. One week after, he had surgery to replace a heart valve. Afterward, Ritenour picked himself up and delivered one of the best albums of his career.

“Those incidents and the support from my family and friends absolutely went into this music,” he says. “Making this record was a lifesaver for me.”

How long had you been planning to record a solo album?

I was thinking about doing this solo project as far back as 2017, and I’d been putting it together in my head for several years. I’ve done so many albums, and I love working with a band. I’m a collaborative guy, and I love to work with great musicians, so I never thought of myself as a solo artist.

I’ve been gradually expanding the solo part of my live show where it is just me, and a lot of people were encouraging me to do something on my own, so I finally decided the time was right. After the fire, I had to start over in a rental house in Marina del Rey, where I set up a recording room from scratch. It felt like the time to finally get down to making the album.

I’m a collaborative guy, and I love to work with great musicians, so I never thought of myself as a solo artist

Was recording the album part of a healing process after your upheavals and problems?

I think so. Not only did I lose the house and everything that was connected with that, but I had also installed a new studio there one year earlier, and I’d moved everything from another location in the city.

Everything was there: about 40 to 50 amps, maybe a hundred guitars, music from since I was 12 years old. A lot of emotion went into this record, and it was a healing process.

This year, 2020, was not only an incredible year in general but it also marked 60 years since I started to play the guitar. So for me, there was a lot of personal imagery and feeling.

Had you been preparing material for the album prior to recording it?

I started collecting ideas over a long period. I’ll sometimes put little pieces of music together and maybe have as many as 30 ideas on my phone while riding around on my bicycle, listening to them, thinking about how to develop them. As I was getting into it heavily toward the end of 2019, everything was going well, and we had a big tour planned.

My idea was to finish it in between tours, but in March, Covid canceled everything, and I found myself at home for the rest of the year like everybody else. For me at that time, there is only one album that I could have worked on anyway. I couldn’t have done a band album during those restrictions. Even my engineer of 40 years, Don Murray, couldn’t come over, so I was completely on my own.

Once I finally got into it and I actually started recording, I started to have a vision of how things were going to be. I got excited, because it was like recording a first album. That was the most delightful part for me – the fact that I could get challenged in that way was a really cool feeling.

Was it liberating to be solely responsible for everything?

It was exactly that. Well put. [laughs] Furthermore, I didn’t have some record company asking me what I was doing or when I was delivering the record. I had signed a deal with Mascot, which was a new relationship. I’d been very much aware of them because of players like Steve Lukather.

When they called, it was good timing, so I was able to license the album to them. Creatively, it was completely up to me, which was also a unique feeling. My old habits still kicked in, though. I ended up producing a record rather than just recording a solo guitar. There was no way I was going to put 12 songs on there with just one sound. [laughs]

You lost an astounding amount of equipment in the fire. Did you lose any of your iconic guitars, like the ES-335?

That day, I was in my car, and my wife was in her car, and we were waiting near the beach to see how things were going to pan out. It became clear that most of the people had vacated earlier. I kept going to the house to check on things, then back to the safe area near the beach, and it was getting worse.

I wondered which guitars I should take... I didn’t even take the most expensive guitars. I just pulled out what I thought was important on that day, but I didn’t actually think the fire was going to burn the house down

Finally, we thought, Okay, maybe we’d better get out of there. We didn’t grab that much, just a few clothes and my basic computer. I wondered which guitars I should take, and I grabbed my ’49 [Gibson] L-5, my 335, a Les Paul, my classical Ramírez and a thousand-dollar Yamaha guitar that I liked the feel of and I’d been using to compose on.

I didn’t even take the most expensive guitars. I actually left a great Les Paul, another L-5 and my Burns of London guitar that I’d had since I was 12. I just pulled out what I thought was important on that day, but I didn’t actually think the fire was going to burn the house down. I walked away thinking I’ll be back tomorrow.

All those guitars, amps, and effects. There were paintings on the wall that were iconic album covers. The music that was inside me still came with me, though. Everybody was so nice after the fire. Fender replaced some amps for me, Xotic built me a new pedalboard. Taylor, Boss, Yamaha, Mesa – they were all incredible.

The album cover features seven guitars. Were they the ones used for the album or the ones that you rescued?

While I did pull seven guitars from the fire, by the time I made the record, Roger Sadowsky had built me a new jazz guitar, Taylor supplied a baritone acoustic, and Yamaha had given me another great guitar. When I did the album cover, I wanted to do this dreamcatcher metaphor, but it was coincidental that it turned out to be seven guitars used on the album and seven guitars that I rescued.

The whole metaphor of the dreamcatcher was really very important for me... I had this idea that the guitars were themselves the dreamcatchers

“Dreamcatcher,” the opening track, seems to capture so many of your influences in one song as they subtly weave around each other. Jazz, classical, blues, and Brazilian music all make an appearance.

Yes, that’s true. It wasn’t the first song that I recorded for the album. I’d already done about six before I got to that. That was the first song, though, where I overdubbed another guitar part; the previous songs had all been exclusively one-guitar pieces. The original idea behind the whole album was to make it exclusively solo, with no overdubs.

When I got to “Dreamcatcher,” I started to come up with ideas, and it needed a second guitar part, which ended up being a lot of the melody. I used exactly the same sound on both guitar tracks. I played pretty sparsely, rather than overwhelming the song with layers of guitar.

The whole metaphor of the dreamcatcher was really very important for me. I was with Dave Grusin in Santa Fe at the end of 2019, where there’s a lot of native American history, and there were a lot of dreamcatchers around. I got interested in the whole dreamcatcher idea, and I had this idea that the guitars were themselves the dreamcatchers.

“Charleston,” the second track, builds on the feel of “Dreamcatcher,” but it has a more traditional jazz guitar sound. The shifting pulses of the track with the propulsive riff and the straighter blues feel keep the listener totally engaged.

Exactly. What went into the song were all those elements of great American rhythms of the U.S. South, even though there isn’t really any blues in the song as such. I wanted to encapsulate everything that I loved best about all the different cultures of American music.

Charleston is infamous for its connection to the beginnings of slavery. It isn’t a city that I travel to very often, but I was there a few years ago. When I played there, it was my first visit in 20 years, and I was entranced by how mixed the audience was: Black and White, young and old.

It was a very soulful crowd. Afterward, we went around the town, and to me it was the modern version of America. I’m sure I’d get some pushback on that from the people who live there. [laughs]

“Lighthouse” features some fantastic Wes Montgomery–style octave riffing. He was a huge influence on me.

The Lighthouse was a famous jazz club in California. It’s still there, but it’s called the Lighthouse Café, and they do a little more blues now. My dad would take me there to hear Wes when I was 13. I’d also hear people like Kenny Burrell, Freddie Hubbard, and Cannonball Adderley.

One day when I came up with the rhythmic pattern for “Lighthouse,” I got out my ’49 L-5 that my dad bought for me when I was 14, and it brought back all those elements. There is a Les Paul part on there, as well, which I recorded by D.I. through a Strymon Iridium [Amp and IR Cab pedal].

I also put two mics on the guitar strings, so there is a bit of rhythmic sound that you can hear as well, which took the Les Paul away from the traditional jazz sound. I was able to orchestrate it so that the two guitars were not competing with each other.

You revisited your old song “Morning Glory” on “Morning Glory Jam.” What made you choose it?

I wasn’t going to put any older material on the record, because five years ago I recorded A Twist of Rit, which was an album full of reworked songs from my career. I kept thinking about how one of my strengths – and something people remarked upon – was my rhythm-guitar playing. I love rhythm guitar, and it is quite an overlooked art.

For some reason, “Morning Glory” came to mind, and I thought about ending the song with a straightforward kind of rhythm-guitar jam. There is no soloing at the end; it is just four rhythm guitars jamming together. It reminded me of what we used to do on the old Barry White sessions.

On the final track, you would not be able to hear the guitars that clearly underneath the voice, the strings, the reverb, and whatever, but they were such fun to record.

There would be me, Jay Graydon, Dean Parks, David T. Walker, and Ray Parker Jr., and we’d all be lined up in a row. Barry White would come up to each of us and sing what he wanted us to play. Some day someone should release those rhythm tracks, because they were really great.

“Abbot Kinney” really jolts the listener with its loud, distorted blues lines. It’s so unexpected after the tracks that preceded it.

When the pandemic happened and everything got shut down, you’d see pictures of deserted big-city streets. One day, I decided I was just going to go for a ride on my bicycle, and I rode over to Abbot Kinney Boulevard [in Los Angeles], and I was shocked by how empty it was, as it was such a popular busy street.

I was sitting there on my bike having a break and a drink of water when I suddenly heard this loud electric guitar coming from a building. It just sounded like someone was really commenting on things, as if to say, “Fuck it,” you know? It just inspired me, and when I got back home, I couldn’t get the feeling out of my head, and I realized that I had never ever done a distortion solo-guitar piece.

There’s a little more delay and reverb on this one, because I wanted to replicate the way that guitar sounded to me, bouncing across the street when I was sitting on my bike.

When you were young, your dad got you some lessons with Joe Pass and Barney Kessel. What kinds of things did you learn from them?

Even at 12 years old we had Wes, Howard Roberts, and Joe Pass albums, you know? I said to my dad how cool it would be to get a lesson from Joe, and my dad just found his number in the book and called him up. [laughs] Back in those days, everybody was listed in the phone book.

We went to his house a couple of times, and in fact he became a friend for many years. I asked Joe, “Mr. Pass, can you teach me to improvise like you?” He would tell me what scales would work over what chord.

I’d say to him, “But Mr. Pass, you don’t sound like you’re thinking of scales when you play.” He said, “Well, I don’t, really. Watch me, and if there’s something you like, I’ll show you how to do it.” He wasn’t a teacher teacher; he was a brilliant guitarist.

Barney Kessel was very interesting. I only took one lesson with Barney. His personality was a little scary, because he was so serious and intense. [laughs] He said to me that he was too busy to teach, really, but it looked like I had some talent, so he said he’d recommend to me the best jazz guitar teacher in L.A., and that was Duke Miller.

Duke was an incredible teacher. For example, we didn’t have chord books; he would have me write my own chord book. He’d teach me a triad, then he’d have me go home and write down every chord I could imagine from it. I’ve realized throughout my lifetime with the guitar what a great visionary and teacher Duke was.

As you say, you’ve been playing for 60 years. What do you think has changed and developed in your own playing? What is different from 20 or 30 years ago?

Well, I was this ubiquitous studio musician, and when I started out, stylistically, I could sound pretty much like any other guitarist and I could fit into any kind of music. When I started to make my own albums, I was really afraid, because I didn’t think I had my own style.

After that very first album in 1976 [First Course], I went back and listened to it a few years later and realized the Lee Ritenour sound was already there. The variety that I loved – be it Brazilian music, rock, jazz, fusion, classical, and blues – all factored into my playing. I’ve been able to change with the times.

If you want to be a professional musician, you want to be able to do it for a lifetime. That means you have to be able to have depth. If you are only able to do one thing, when that one thing goes out of style, it’s over. The key is to keep fresh, keep changing, and keep finding challenges. This solo album was a challenge for me.

Given how many years you spent working as a first-call session guitarist, what was the secret to playing on tracks that you didn’t particularly like very much?

You have to understand that for 80 percent of the sessions that we all worked on, most of the music wasn’t very good. [laughs] When someone interviews a famous studio musician and they say they worked with Michael Jackson or Pink Floyd or whoever, they’re the easy ones.

There is a craft. It’s a case of thinking, let’s see what I can do to find a way to make this song sound better and maybe make this artist sound better. If I was playing with a live rhythm section, most of the time they would all be great musicians, and so that was always a joy anyway.

The internet is full of people with great technical skills these days, but not necessarily with great musicality. What do you think someone should do to bring some soul to their playing? How does a musician find their own voice?

Anywhere in the world now, you can hear a five-year-old copying someone’s astounding solo perfectly, and they’ll have a million views on YouTube. However, does that little kid who is copying a Jeff Beck solo know what Jeff did to get that? The depth that goes into creating your own style and your own voice is much, much harder to achieve.

Compose your own music. That is probably the best way to find out who you are and to make more of an identity for yourself

I think using the culture of where you come from is one key to finding a unique voice, drawing on whatever music is indigenous to where you are. The other important thing is to compose your own music. That is probably the best way to find out who you are and to make more of an identity for yourself.

I always say the genius is in the conception, not the execution.

Yes, very much so. It’s like a lot of people say about things: “Well, that’s not so hard!” [laughs] Not a single lick that I play on this album is that hard to play. Technically, it’s not so hard compared to what a lot of people can play. However, creating 12 songs that can hold your attention and make an interesting statement, that maybe take you on an emotional journey – that’s not easy.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.