Hear These Fine Vintage Martins in Action on Collector and Bluegrass Ambassador Gary Brewer’s Latest Cut, ‘House of Axes’

‘House of Axes’ is a straight-shooting showcase for Brewgrass’s rarest and most prized acoustics from a collection of more than 100 vintage Martins

If there’s a home where any true acoustic guitar aficionado would dream to reside, it’s Gary Brewer’s House of Axes. Brewer is best known as the leader of the long-thriving Kentucky Ramblers, a family band whose 2020 release, 40th Anniversary Celebration, spent 16 weeks at number one on the Billboard Bluegrass Albums Chart, was the number-three best-selling project overall in 2021, and landed between releases by Ariana Grande and Rob Zombie on the Top Current Albums Sales year-end chart.

Brewer is quite a character, who prefers colorful clothes and refers to his high-octane Americana as “Brewgrass,” but he’s as legit as they come, with the history and testimony to prove it. Brewer’s grandfather worked with the original Carter Family in the ’20s, and the Brewer family is now a six-generation musical dynasty.

As Brewer explains, Father of Bluegrass Bill Monroe played his final recording session with him and was quoted saying, “This boy right here is 100 percent bluegrass! He comes from good stock.” George Gruhn, acoustic guitar guru and owner of renowned Gruhn Guitars in Nashville, sings his praises as well, saying, “Gary Brewer is to the guitar what Bill Monroe was to the mandolin.”

Brewer has amassed a monumental arsenal of guitars, including 100 vintage Martins that date back to 1899. His new guitar concept project, House of Axes (SGM), is a straight-shooting showcase for his rarest and most prized acoustics. It’s a multimedia affair, captured at Brewgrass Entertainment, headquarters for the family business, where he sat down with nine select instruments and proceeded to play them one at a time, offering insights on each before launching into stellar song performances captured raw in the moment with one take and no overdubs. You can watch them in a revealing series of YouTube videos or listen to the audio versions, where each introduction is broken out as a separate track.

What you’ll experience is a master picker throwing down time-honored tunes from the classic bluegrass canon on museum-quality guitars. They come alive in his capable hands with every nuance of technique and instrumental overtone gloriously clear to hear. Each axe has a tale to tell, and Brewer touches on them in the recordings and extensive liner notes. But as we discovered, there’s a hell of a lot more to the story.

Brewer’s ultra-rare, all-original 1899 Martin 0-28 Herringbone has herringbone binding, a zipper back, etched keys, ivory tuners, a notched headstock and ivory pins. The Martin logo is stamped on the headstock’s back. The guitar is so rare, even Martin Guitars’ own museum doesn’t have an example. “They’ve offered an undisclosed amount of money, but I’ve told them no go,” Brewer says. “It’s a holy grail.”

Brewer’s ultra-rare, all-original 1899 Martin 0-28 Herringbone has herringbone binding, a zipper back, etched keys, ivory tuners, a notched headstock and ivory pins. The Martin logo is stamped on the headstock’s back. The guitar is so rare, even Martin Guitars’ own museum doesn’t have an example. “They’ve offered an undisclosed amount of money, but I’ve told them no go,” Brewer says. “It’s a holy grail.”

Brewer’s ultra-rare, all-original 1899 Martin 0-28 Herringbone has herringbone binding, a zipper back, etched keys, ivory tuners, a notched headstock and ivory pins. The Martin logo is stamped on the headstock’s back. The guitar is so rare, even Martin Guitars’ own museum doesn’t have an example. “They’ve offered an undisclosed amount of money, but I’ve told them no go,” Brewer says. “It’s a holy grail.”

Brewer’s ultra-rare, all-original 1899 Martin 0-28 Herringbone has herringbone binding, a zipper back, etched keys, ivory tuners, a notched headstock and ivory pins. The Martin logo is stamped on the headstock’s back. The guitar is so rare, even Martin Guitars’ own museum doesn’t have an example. “They’ve offered an undisclosed amount of money, but I’ve told them no go,” Brewer says. “It’s a holy grail.”

Brewer’s ultra-rare, all-original 1899 Martin 0-28 Herringbone has herringbone binding, a zipper back, etched keys, ivory tuners, a notched headstock and ivory pins. The Martin logo is stamped on the headstock’s back. The guitar is so rare, even Martin Guitars’ own museum doesn’t have an example. “They’ve offered an undisclosed amount of money, but I’ve told them no go,” Brewer says. “It’s a holy grail.”

What inspired you to make House of Axes?

It’s well known that I’ve got a good guitar collection, and every time I go out to perform, somebody asks, “Which axes did you bring?” I can’t show them all, and I realize that some are rather monumental in the guitar world as well as to me, personally. That prompted me to record them on video and audio to let people see and hear them. The goal was to do so very clearly. We used the same pair of microphones with the dials set at zero, so everybody sure enough could hear the nuances of each guitar, from the highs to the lows and everything in between, kind of like being there. I wanted people to hear the insides of those guitars, not flavor ’em up, which happens a lot in the guitar world. They can be knobbed too much. You get more of the sound the player wants you to hear, but I wanted just the opposite. I wanted the listener to hear the guitar, and then the player.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How did you capture the tones?

There’s a large-diaphragm condenser mic pointed toward the bridge, and a small-diaphragm condenser pointed where the neck meets the body, because I like a certain degree of string and finger noise – not too much, but just enough so the listener can determine when I’m sliding, hammering on or pulling off a note. I usually point the mic where the neck and body meet, rather than higher up between the12th and 15th frets, where most people do. I still get the harmonics, like I do on “Sourwood Ridge,” but they’re not pulled out to stand out. I like the larger-diaphragm microphone pointed at the bridge because that’s where the sound really resonates. I like to tap into as much of that as I can, to get the whole sound of the guitar without going into the sound hole.

I’ve got over a hundred vintage Martins in my collection and nothing is newer than 1968, which is the last full production year using Brazilian rosewood

Gary Brewer

I use a pretty big thick pick, a triangular BlueChip TAD50 for quick economy of motion. I use Mapes strings, which is the oldest string company in the world. They’ve turned strings for everyone, including D’Addario. I use a special medium set of phosphor-bronze strings that Mapes makes for me, with gauges ranging from .012 to .056. To preserve them, they’re actually coated in East Tennessee moonshine. They come in a vacuum-sealed envelope with three sets. As for the recording itself, the set on every guitar was at least a month old, and the ones I used on the 1899 Martin single-ought were over two years old.

Where does that jewel sit in your overall collection?

I’ve got over a hundred vintage Martins in my collection and nothing is newer than 1968, which is the last full production year using Brazilian rosewood. Martin made about 1,959 of them, and there aren’t many spoken for now. They’ve been lost somewhere. On House of Axes, I played “Sourwood Ridge” in Drop D tuning on the ’68 D-28. That guitar is very special to me because it was my first Martin. My dad bought it for me when I was a young lad, and I recently gave it to my son Wayne for his 25th birthday. As for the 1899 single-ought, that’s an incredibly historic Herringbone, as is my main axe that I’ve been touring with for over 40 years, which is a 1941 D-28 Herringbone. I also have one from the year 2000, so I have three all-original Herringbone models from three centuries, which is pretty cool.

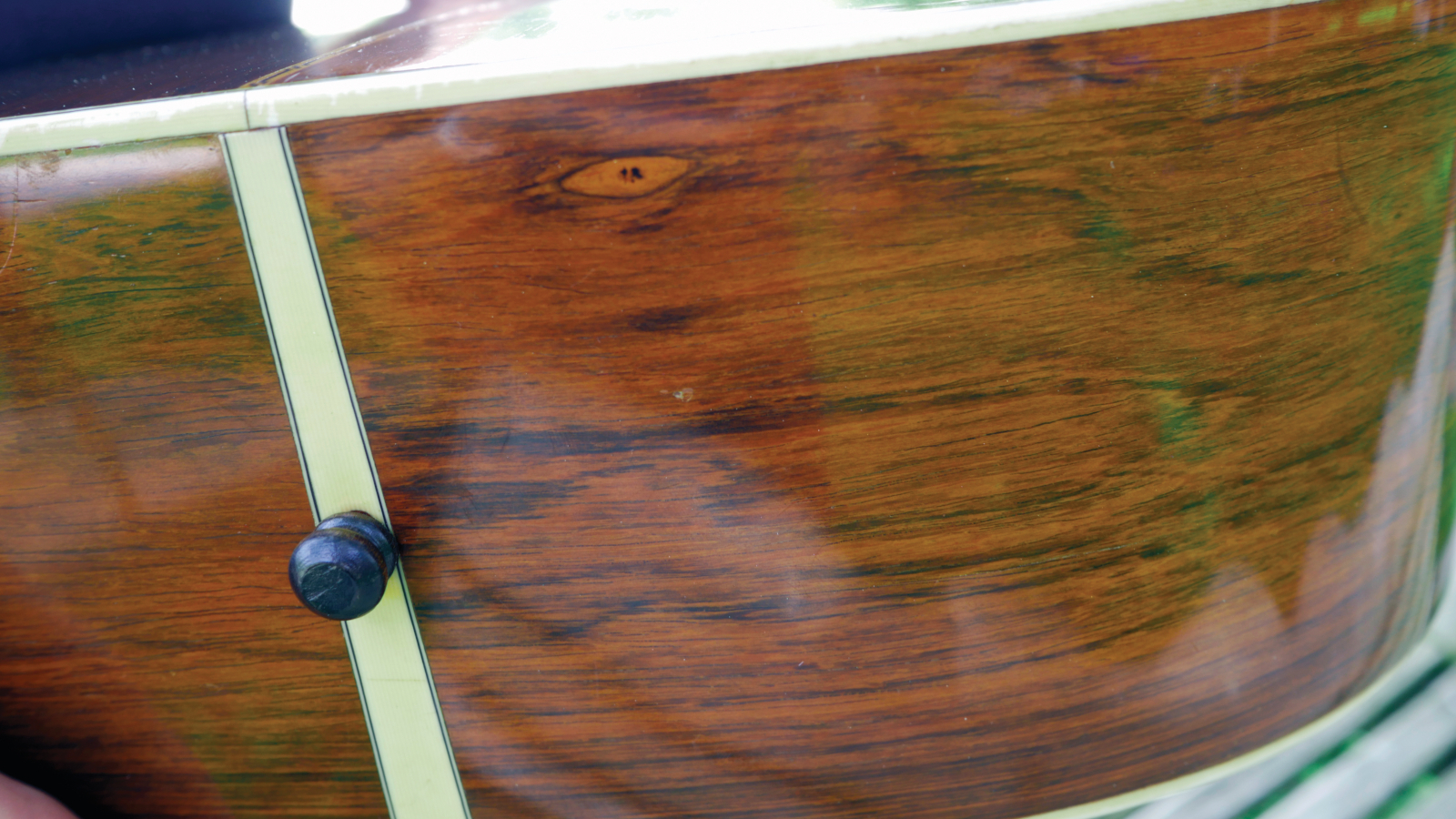

Brewer describes this 1948 Martin D-28 in the liner notes for House of Axes as “a really unique guitar,” and indeed it is. It’s one of just 506 manufactured and is all original. “It has some really pretty beauty marks,” Brewer says. “Looks almost like half of a coffee cup marking there, and it’s probably got one of the prettiest backs of any of my guitars.”

Brewer describes this 1948 Martin D-28 in the liner notes for House of Axes as “a really unique guitar,” and indeed it is. It’s one of just 506 manufactured and is all original. “It has some really pretty beauty marks,” Brewer says. “Looks almost like half of a coffee cup marking there, and it’s probably got one of the prettiest backs of any of my guitars.”

Brewer describes this 1948 Martin D-28 in the liner notes for House of Axes as “a really unique guitar,” and indeed it is. It’s one of just 506 manufactured and is all original. “It has some really pretty beauty marks,” Brewer says. “Looks almost like half of a coffee cup marking there, and it’s probably got one of the prettiest backs of any of my guitars.”

Can you speak to the significance of a Herringbone compared to, say, a standard Martin in style 28?

It signifies the herringbone binding around the front of the body, just like a herringbone necklace. Up the center of the back of the body is what they commonly call the “zipper stripe.” A Martin Herringbone is a very iconic and sought-after instrument. On a vintage Herringbone, each little piece is cut and set in there by hand, whereas today it’s just one long piece of binding. The luthiery workmanship on the originals is amazing, with pieces of light versus dark wood that gives that herringbone effect. My ’41 represents what collectors call the “true” Herringbone, which Martin only made from 1934 to 1944.

Martin did make Herringbones in ’45 and ’46, but they aren’t considered true Herringbones because they didn’t have scalloped bracing or snowflake inlays on the fretboard; they just had the dots of a standard style 28. There are lots of little significant things that set each century of Herringbone apart. They call the 2000 millennium issue an HD-28 Herringbone. That’s basically a new version of my ’41 Herringbone, which is like a full-sized version of the 1899 0-28 Herringbone.

You only played the two vintage Herringbones on House of Axes, correct?

Right. Other than the inclusion of a few makes and models that are significant to me – such as my father’s 1957 Silvertone that I used on “Little Brown Jug,” or a guitar that I endorsed at one point or another, such as the 1992 Mossman Texas Plains model on “White Horse Breakdown” and the 1997 Stelling RHD-125 on “Tom Rock Twist” – the acoustics on House of Axes were mainly chosen for their historical importance and rarity.

A Martin Herringbone is a very iconic and sought-after instrument. On a vintage Herringbone, each little piece is cut and set in there by hand

Gary Brewer

The 1948 D-28 I used on “Old Minor Joe” is one of 506 ever made. Tony Rice tried to buy that one off of me, but I’m a hard negotiator, and he didn’t get it! The gorgeous 2007 Martin D-41 Porter Wagoner Custom Signature that I used on “Southern Flavor” is number 24 of only 71 ever made. That was commissioned by Marty Stuart as a tribute to Porter, and it boasts both Marty’s and Porter’s signatures. The guitar on “Little Rosewood Casket” is one of only 176 Martin D-28s made in 1959 with an “E” designation, which stood for “electric” because it had a rudimentary pickup system onboard. The capo I used at the fourth fret is an old spring type that belonged to Lester Flatt.

My main Martin, the ’41 Herringbone, is one of 183 ever made, and she’s still doing good. I can get any sound I want out of that guitar. My friends sometimes call it the Old Bone, or the Killer. You can hear that on the first track, Norman Blake’s “Old Brown Case.” On most dreadnoughts you lose a lot of power and rear end once you get up past the sixth or seventh fret, especially on the first few strings, but notice how I’ll go all the way up to where the neck meets the body and those notes are still as prominent as the bass notes.

The 1899 single-ought Martin Herringbone is one of only 49 ever made, and mine is all original. It has etched keys on a notched headstock with downward-facing tuners. The tuners and bridge pins are made of real ivory, which is wild to even think about today. Martin dug up some information for me. It was ordered from a catalog and delivered by horse to the original owner.

Brewer’s 1941 Martin D-28 Herringbone is “my main axe that I’ve been touring with for over 40 years,” he tells Guitar Player. As he explains in the House of Axes liner notes, the guitar is all-original and is one of just 183 ever made. This guitar represents a true Herringbone, which Martin made between 1934 and 1944. “Martin did make Herringbones in ’45 and ’46,” Brewer tells us, “but they aren’t considered true Herringbones because they didn’t have scalloped bracing or snowflake inlays on the fretboard; they just had the dots of a standard style 28.”

Brewer’s 1941 Martin D-28 Herringbone is “my main axe that I’ve been touring with for over 40 years,” he tells Guitar Player. As he explains in the House of Axes liner notes, the guitar is all-original and is one of just 183 ever made. This guitar represents a true Herringbone, which Martin made between 1934 and 1944. “Martin did make Herringbones in ’45 and ’46,” Brewer tells us, “but they aren’t considered true Herringbones because they didn’t have scalloped bracing or snowflake inlays on the fretboard; they just had the dots of a standard style 28.”

Brewer’s 1941 Martin D-28 Herringbone is “my main axe that I’ve been touring with for over 40 years,” he tells Guitar Player. As he explains in the House of Axes liner notes, the guitar is all-original and is one of just 183 ever made. This guitar represents a true Herringbone, which Martin made between 1934 and 1944. “Martin did make Herringbones in ’45 and ’46,” Brewer tells us, “but they aren’t considered true Herringbones because they didn’t have scalloped bracing or snowflake inlays on the fretboard; they just had the dots of a standard style 28.”

Tell us how you managed to acquire it.

I bought it from the daughter of the original owner. I had an annual festival called Strictly Bluegrass, and we were in the Kentucky Derby Festival doing the Pegasus Parade through downtown Louisville promoting the event. We had a sign up with a little old prop guitar, just for a visual. I had put “THANKS” in masking tape on the back, to be like Ernest Tubb’s guitar. An elderly lady who was close to her nineties said, “Play me one there on that guitar.”

I said, “Honey, it’s just a prop guitar. It doesn’t even have strings on it.” She said, “I have one just about that size. It’s an Italian model, something like a Martini. My mother bought it new, and I’d just about give that to somebody if they’d play it.” Of course, my radar went off, and I got her number. It was very near my birthday, April 19th, almost 30 years ago. I made arrangements for my dad and I to go over there. She brought that thing out and I’d like to have fell in the floor.

I called a friend of mine with some measurements. He told me, “Make sure you do not leave that house without that guitar.” I said, “Name a price,” and when she did I told her, “Honey, that’s not enough money. That guitar is worth a lot more.” I tripled her offer and needless to say, I still got a heck of a deal.

What does it feel and sound like from a player’s perspective?

Amazingly, it’s a player’s guitar. A lot of the old parlor-type Martins weren’t up to today’s performance standard, but that one is. Because of the single-ought’s smaller body size measuring 13.5 inches wide at the bridge, it rides good under the arm and on the knee. It’s actually much larger than some of the smaller Martins of the era, and of course the single-ought eventually evolved into full-sized dreadnought D-28.

I like the different feel of the open headstock, and I appreciate having the tuning keys pointed down from its back, because if you need to reach up and make an adjustment, it’s right there where you can easily reach up with your left hand. Of course, it needs to be carefully placed in an appropriate case to avoid breaking the tuners, but otherwise, I don’t know why more guitars aren’t made like that. Anyway, it just feels and plays wonderful. Oddly enough, the neck feels a lot like a Gretsch 6120 [Chet Atkins] Hollow Body electric, which is a dream.

I’m honored and excited to put that guitar on House of Axes. I chose to play a song my paw-paw played, which is actually a mix-up of two old tunes: “Foggy Mountain Top/Lonesome Road Blues.” He never used picks; he was a two-finger player. I tried to play it just as close to the way he did, so I used my fingers. That alone speaks volumes in the guitar world, because the mics are set the same as for the other tracks played with a pick, and it holds up in terms of volume and clarity.

The tone is amazing, and to my knowledge this is the first time that guitar has ever been recorded. It is so rare they don’t even have one in the Martin Museum. They’ve tried every way to get that guitar from me. They’ve offered an undisclosed amount of money, and even other guitars, like the $50,000 Celtic Knot, but I’ve told them no go. I had to work really hard to get that guitar. It’s a holy grail.

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com