Discover Dickey Betts’ Inspired Guitar Playing Approaches on the Allman Brothers Band’s Best-Selling Studio Album, ‘Brothers and Sisters’

The guitarist-vocalist augmented the group’s groundbreaking amalgamation of rock, blues, jazz and country on this pivotal 1973 LP

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

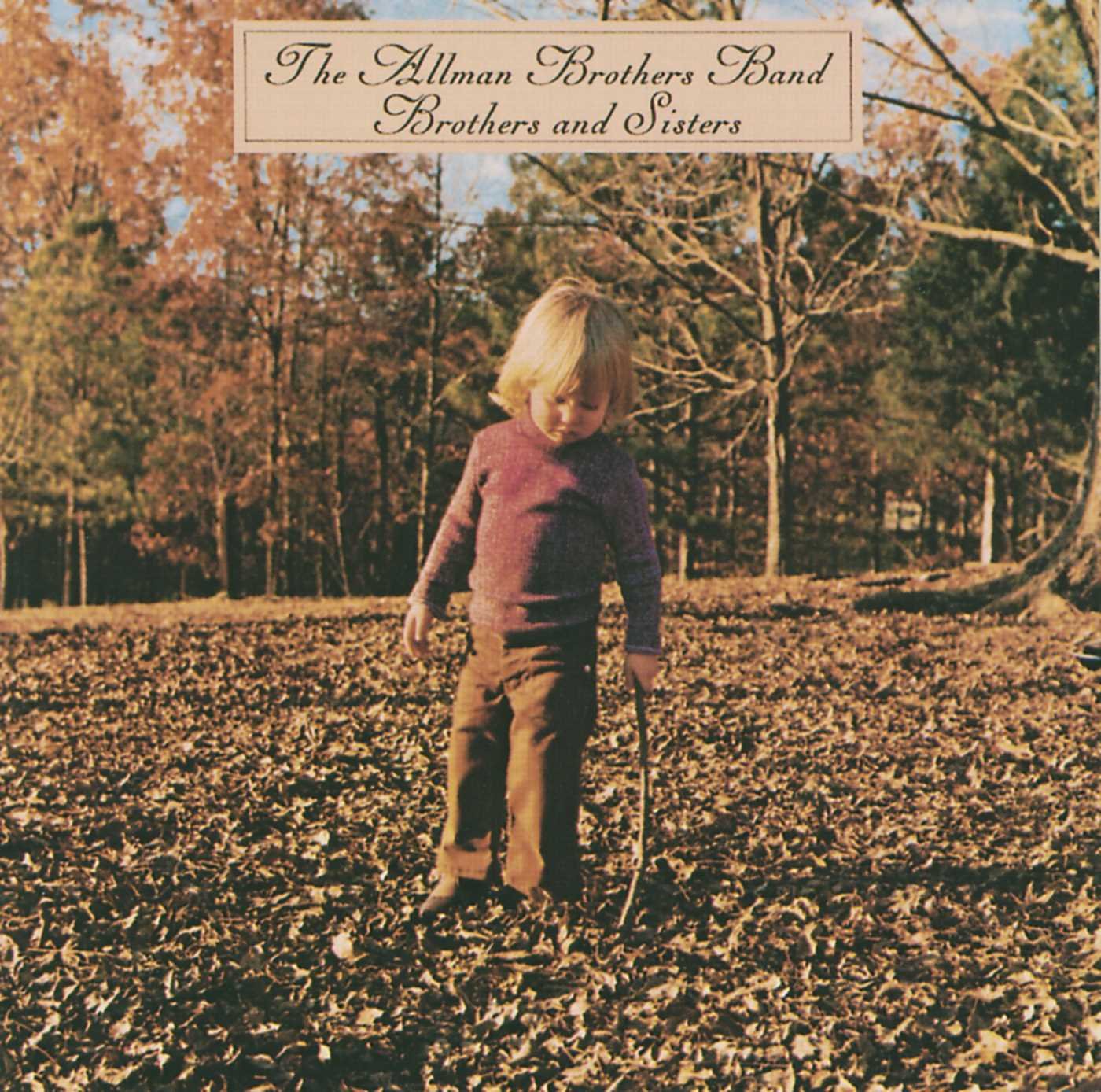

The 1970s constitute classic rock’s grittiest and perhaps most prized decade. With the dawn of 2020, it also became a decade full of half-century milestones, with 1973 the current epoch du jour. In addition to herculean releases like Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy and the Who’s Quadrophenia, the Allman Brothers Band’s Brothers and Sisters album ascended the charts, despite the band’s considerable personnel challenges.

With the group still reeling from the tragic loss of bassist Berry Oakley during the recording process – his demise was eerily reminiscent of guitarist Duane Allman’s monumental passing only one year earlier – guitarist Dickey Betts took the reins and led the band into what would be its most commercially successful era.

The band recorded the album’s tracks between October and December 1972, with the help of Chuck Leavell on piano and Oakley’s replacement, LaMar Williams, on bass, as well as session guitarists Les Dudek and Tommy Talton.

Released in August 1973 on Capricorn Records, Brothers and Sisters went on to sell more than seven million copies, making it the ABB’s all-time best-selling album. At this juncture, Betts assumed an unofficial leadership role and wrote more than half the songs on Brothers and Sisters. In doing so, the guitarist-vocalist augmented the band’s groundbreaking amalgamation of rock, blues and jazz with country music elements, most notably on songs like the Dobro-driven “Pony Boy” and the autobiographical “Ramblin’ Man.” The latter validated the shift as “Ramblin’ Man” would go on to reach number two on the Billboard Hot 100 and become a beloved southern rock anthem.

Alongside the success of “Ramblin’ Man,” which would be the last song Berry Oakley would record with the band, Brothers and Sisters included two more future staples composed by Betts. Contrary to the emerging country influence was a more Brothers-like blues-rock vibe in “Southbound” and the commemorative instrumental “Jessica.” The latter was an homage to Django Reinhardt – one of Dickey’s idols – as much as it was a loving tribute to his daughter, for whom the song is named.

Despite losing two founding members, the Allman Brothers Band prevailed with Brothers and Sisters, while Betts furthered his own legend. In this lesson, we’ll investigate some of Dickey’s signature playing approaches on the album – including some that may fall under the radar – starting with a look at “Ramblin’ Man.”

Take note: “Ramblin’ Man” was recorded in standard pitch and played as if it were in the key of G, but a tape machine function called varispeed was deliberately used in the mastering process to speed up the song a little, causing it to be heard a half step higher, in the concert key of A flat.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

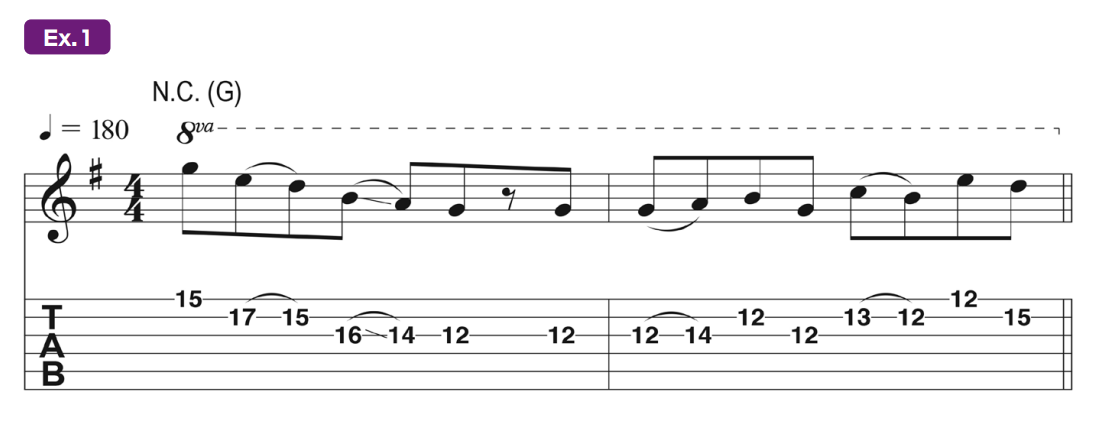

Sometimes all it takes is a modest call-and-response hook to sear a song’s identity into the hearts of millions, and “Ramblin’ Man” does just that. Ex. 1 is a two-bar lick inspired by Dickey’s eloquence in the track’s opening moments.

The gold here is his use of the six-note G major hexatonic scale (G, A, B, C, D, E). The major hexatonic excludes the 7th degree (F#) of the conventional seven-note (heptatonic) G major scale (G, A, B, C, D, E, F#), and it fuels much of what Dickey plays throughout his melodic and soloistic performance on this song as well as many others.

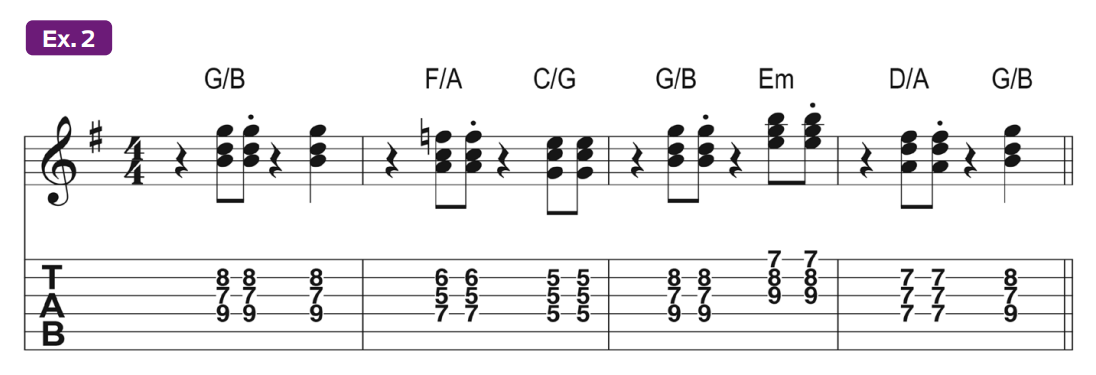

Before we inspect any more lead-playing action, it’s important to acknowledge the rock-solid rhythm playing of Dudek. On “Ramblin’ Man,” the guest sideman lays down, on a clean electric guitar, a bed of crisply articulated chords for Betts and the band to play along with throughout the arrangement, much as he does with acoustic guitar on “Jessica.”

Stationed mostly on the D-G-B string group, Dudek plays close-voiced triads with an emphasis on beats 2 and 4 – what are known as the backbeats – and peppers them with a staccato attack on the following upbeat.

Ex. 2 similarly presents a condensed version of the chords played throughout the song’s verse and chorus sections. With the exception of the root-position Em shape played on the top three strings, these voice-led triads are evenly split between pairs of 1st- and 2nd-inversion voicings: G/B and F/A, and C/G and D/A, respectively.

Betts’ soloing style is characterized not only by his copious use of the major hexatonic scale but also by his tastefully poised melodic phrasing.

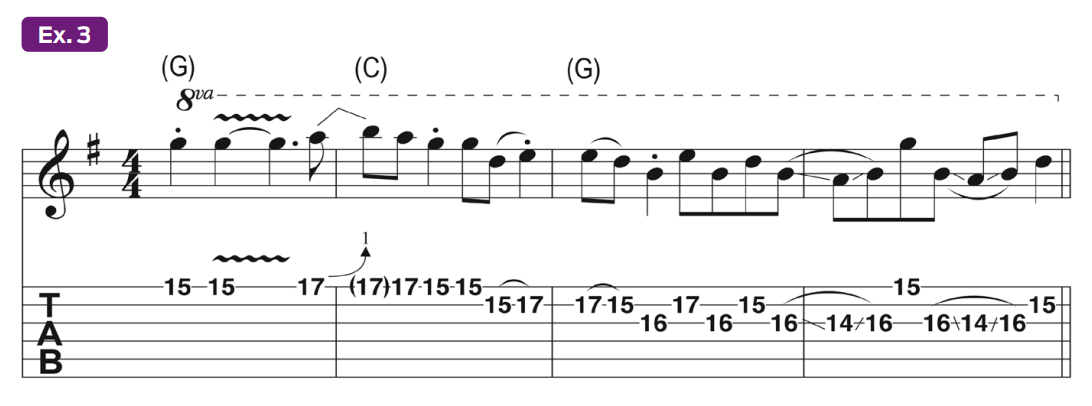

Looking at Ex. 3, a reworking of what the guitarist plays at the beginning of his “Ramblin’ Man” solo, you can see two key elements on display.

First is the use of space in the form of staccato quarter notes, which serve to punctuate the eighth-note rhythms nicely.

Second is the use of legato articulations, such as string bends, hammer-ons and pull-offs, which function like “vowels” that break up and smooth out the picking while still clearly conveying the eighth-note rhythms.

Bars 3 and 4 demonstrate another signature Betts move, with the use of descending and ascending whole-step finger slides on the G string that playfully ricochet while also ping-ponging with picked notes on the B and high E strings, all while targeting the tones of the underlying G chord – G, B and D.

Dickey employs these and other techniques in endlessly fresh ways with a characteristically lyrical approach to arpeggio-based soloing that never sounds contrived.

Another hallmark of Betts’ phrasing style is his penchant for dramatic rhythmic shifting and parallel modulation.

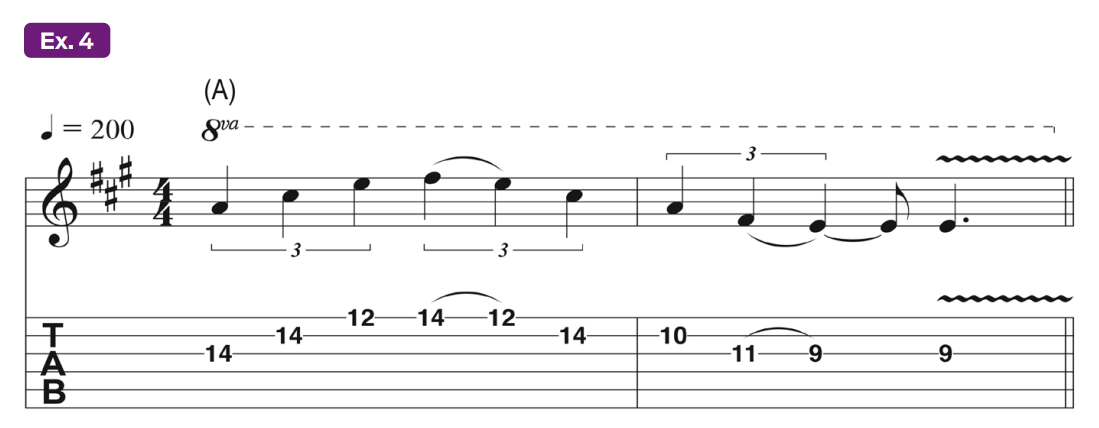

Ex. 4 is modeled after a moment in “Jessica” where the band completes the song’s third cycle through the head melody. Here, the guitarist throttles back the vibrant momentum of the A major hexatonic (A, B, C# , D, E, F# ) two-part harmony licks that are played with a straight-eighths feel by “downshifting” to quarter-note triplets.

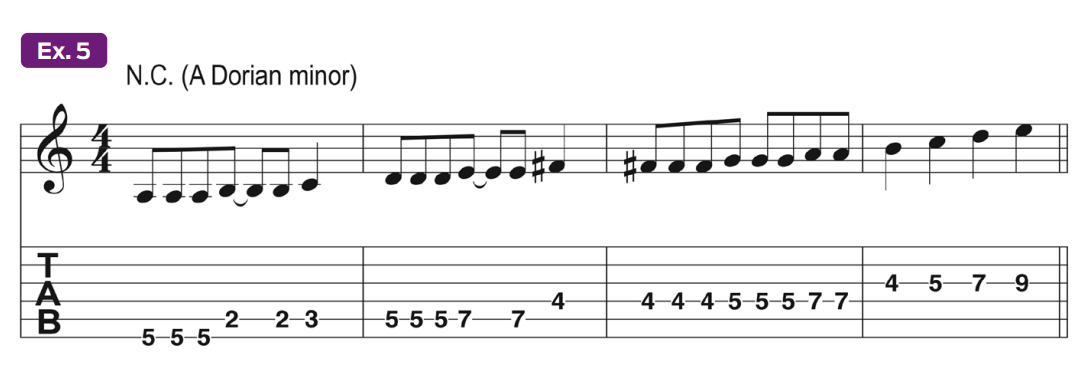

Following Leavell’s brilliantly melodic piano solo over Dudek’s locomotive acoustic rhythm in “Jessica,” Betts once again transforms the streaming-eighth-notes rhythmic feel, this time while also transmuting the tonality, with a climatic, syncopated ensemble riff that’s an ascending line based on the parallel A Dorian mode (A, B, C, D, E, F# , G), which informs Ex. 5.

If you’re unfamiliar with Dickey’s soloing style and sound, and you are starting to develop an overall assessment of his playing and tonal choices based on what’s been laid out so far, hold the phone. The guitarist’s improvising prowess does not solely make use of subdued overdrive tones as he expertly wields major-based melodic devices.

Consider “Southbound,” a funky uptempo Memphis soul-flavored jam song based on a I - IV - V 12-bar blues progression in the key of C, made up of all dominant 7th chords (I: C7, IV: F7, V: G7). Betts reels you in from the track’s opening lick, which is based on the C minor pentatonic scale (C, Eb, F, G, Bb), by sporting a comparatively pronounced increase in gain, with an upward tick in the mids to spice up his infamous middle-pickup setting on a humbucker-equipped Les Paul plugged into a 100-watt Marshall stack.

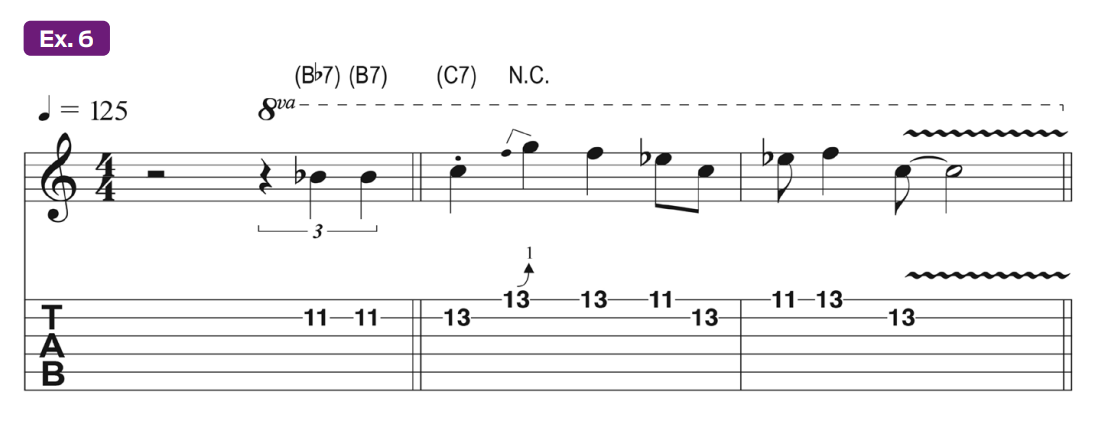

Ex. 6 does something similar, offering a taste of the tension created by playing the minor 3rd, Eb, over the major 3rd, E, that lives in the underlying C7 chord (C, E, G, Bb), which, in “Southbound,” the band chromatically ascends to from Bb7 (Bb7 - B7 - C7).

Dickey’s two solos in “Southbound” also highlight a few more of the guitarist’s celebrated moves, such as his use of call-and-response phrasing, with which he crafts catchy, unforgettable hooks.

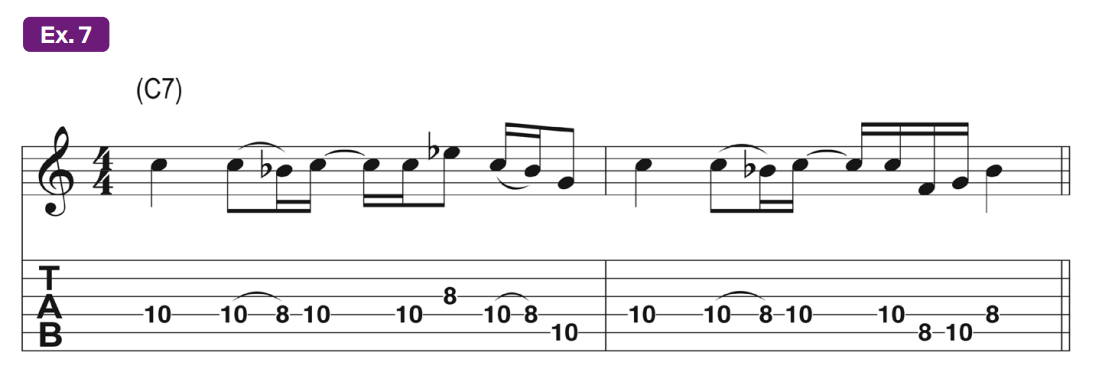

Ex. 7 is inspired by a salvo in his first solo, where he digs in with a short motif over C7, again using notes from C minor pentatonic.

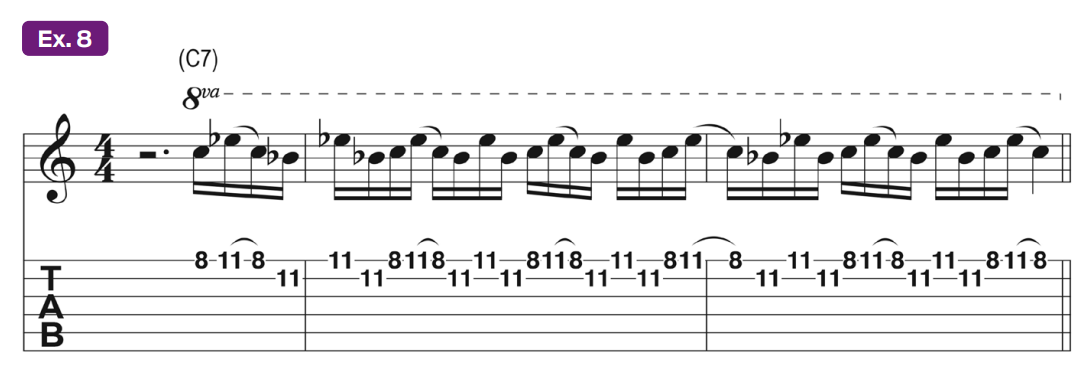

Based on the same scale, Ex. 8 is modeled after a dense 16th-note phrase Dickey plays over two bars of C7 a little later.

Notice the way the six-note pattern repeats, producing a rhythmically dramatic hemiola as the motif shifts forward by half a beat with each repetition.

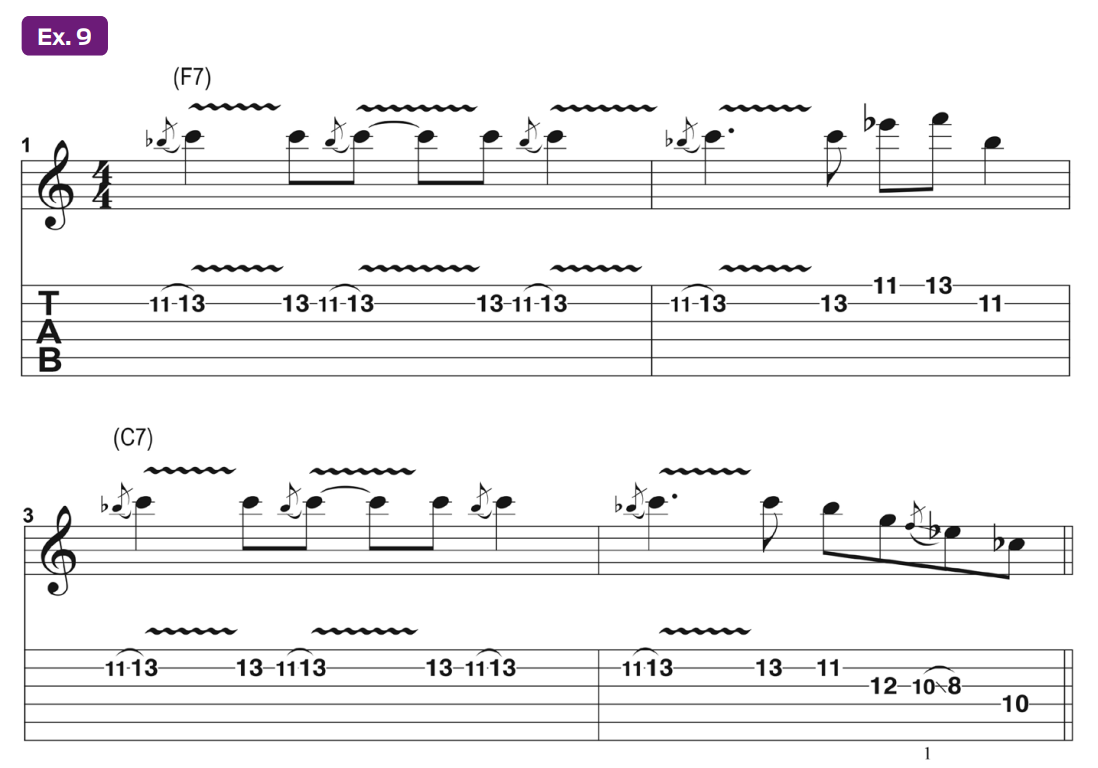

Ex. 9 presents a reworking of what Betts plays in his second solo, where he offers some southern musical hospitality in the form of poised call-and-response coupled with repetition over F7 and C7 chords.

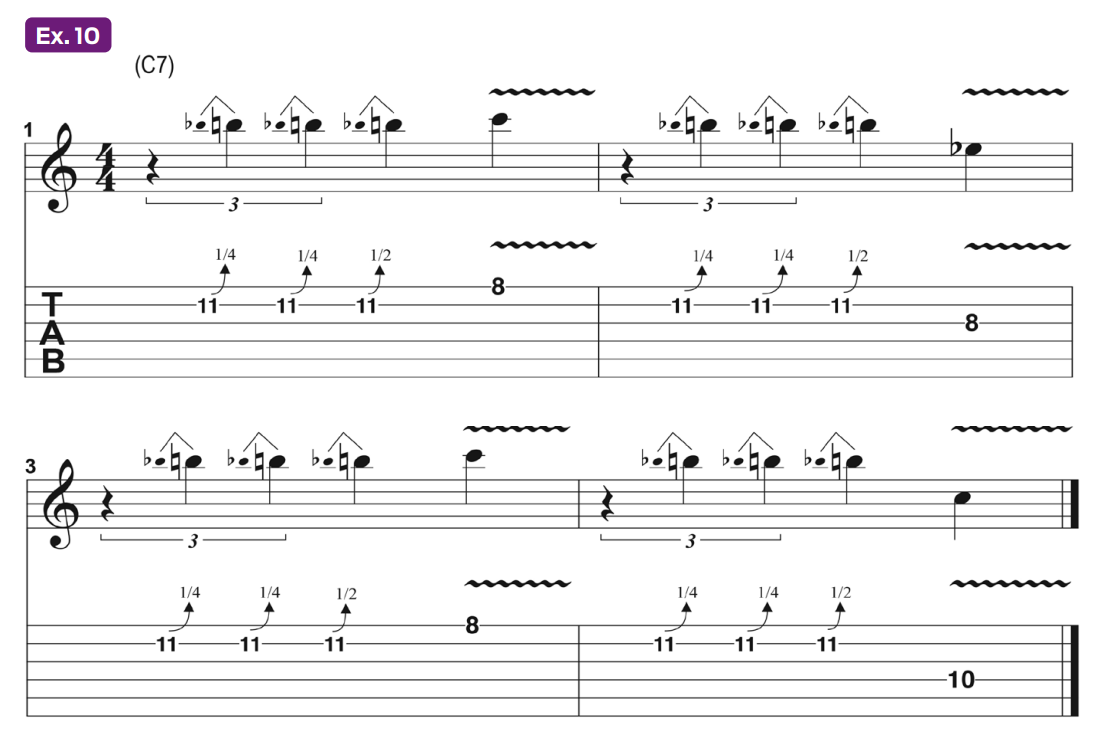

Finally, Ex. 10 is in the spirit of what Dickey lays down over the I chord to open his final pass through the changes.

Super-catchy licks like this not only take the audience to the peak of a musical rollercoaster ride but also cue the band to close out the song.

While Dickey Betts’ creative contributions on Brothers and Sisters are undeniable, that’s not to say the remaining blood brother was absent from the process, nor did his legendary gruff go unheard. In fact, most of the original album’s side one features Gregg Allman singing his own tunes, including the opening track “Wasted Words,” “Come and Go Blues” and the Billy Eckstine standard “Jelly Jelly.”

As for side two, it’s the Dickey Betts show. And while Gregg’s vocal growl is crucial to the soulful impact of “Southbound,” it’s Dickey’s guitar lines that steal the show as they weave in and out of Allman’s vocal performances with his unmistakable and tasteful style.

Order Brothers and Sisters by the Allman Brothers Band here.

Chris Buono is a top-selling TrueFire Artist with nearly 50 instructional videos, and a featured instructor on guitarinstructor.com. Bookending his years as a Berklee professor, he authored eight books, including the popular Guitarist’s Guide to Music Reading and his most recent publication, How to Play Outside Guitar Licks.