Watch Chuck Berry Perform His Breakthrough Hit, “Maybellene,” Live on TV

Five years on from his passing, we share the fascinating story behind the Father of Rock ‘n’ Roll’s pioneering classic.

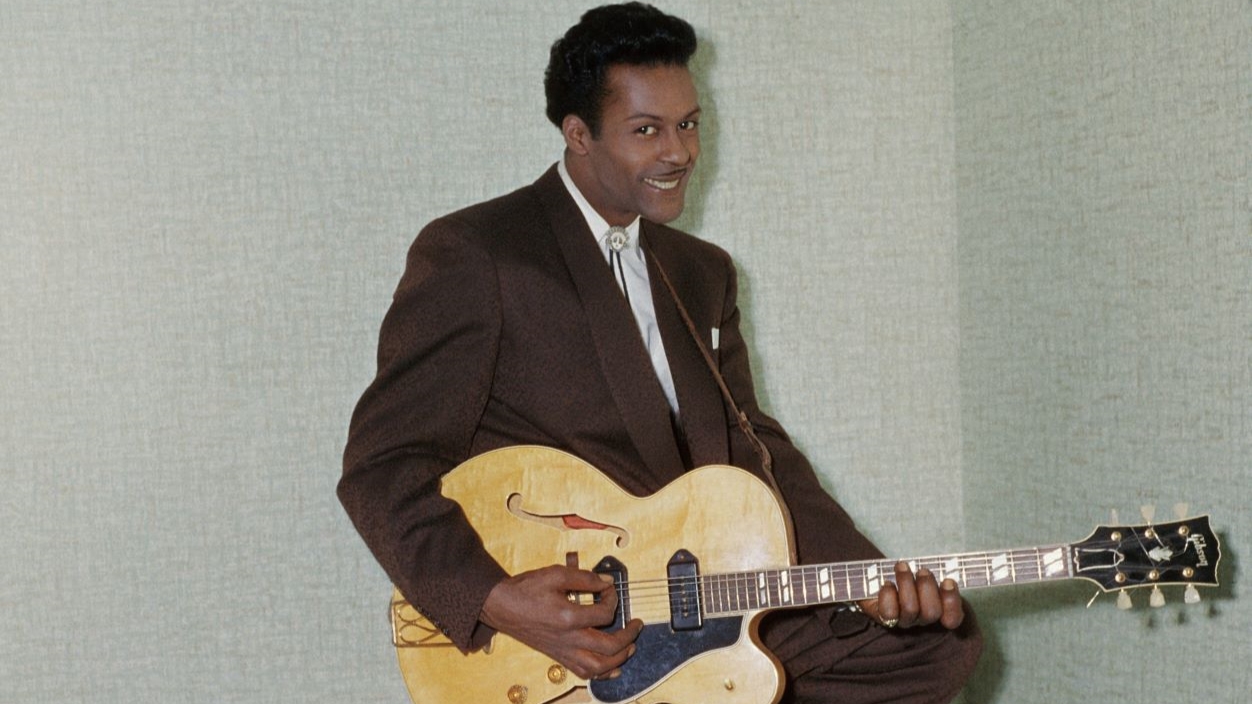

By the mid-1950s, Chuck Berry had begun writing songs and felt he was ready to record them. In May 1955, he drove from St. Louis to Chicago, where he planned to see his idol, Muddy Waters, perform a Friday night show.

“And I listened to him for his entire set,” Chuck recalled to NPR in 2000. “When he was over, I went up to him, I asked him for his autograph and told him that I played guitar.”

But Chuck had something more on his mind. “How do you get in touch with a record company?” he asked. Muddy suggested he try his boss, Leonard Chess, over at Chess Records.

That Monday morning, Chuck intercepted Chess as he walked into the studio and made his pitch. Chess told him to return in a week with a demo.

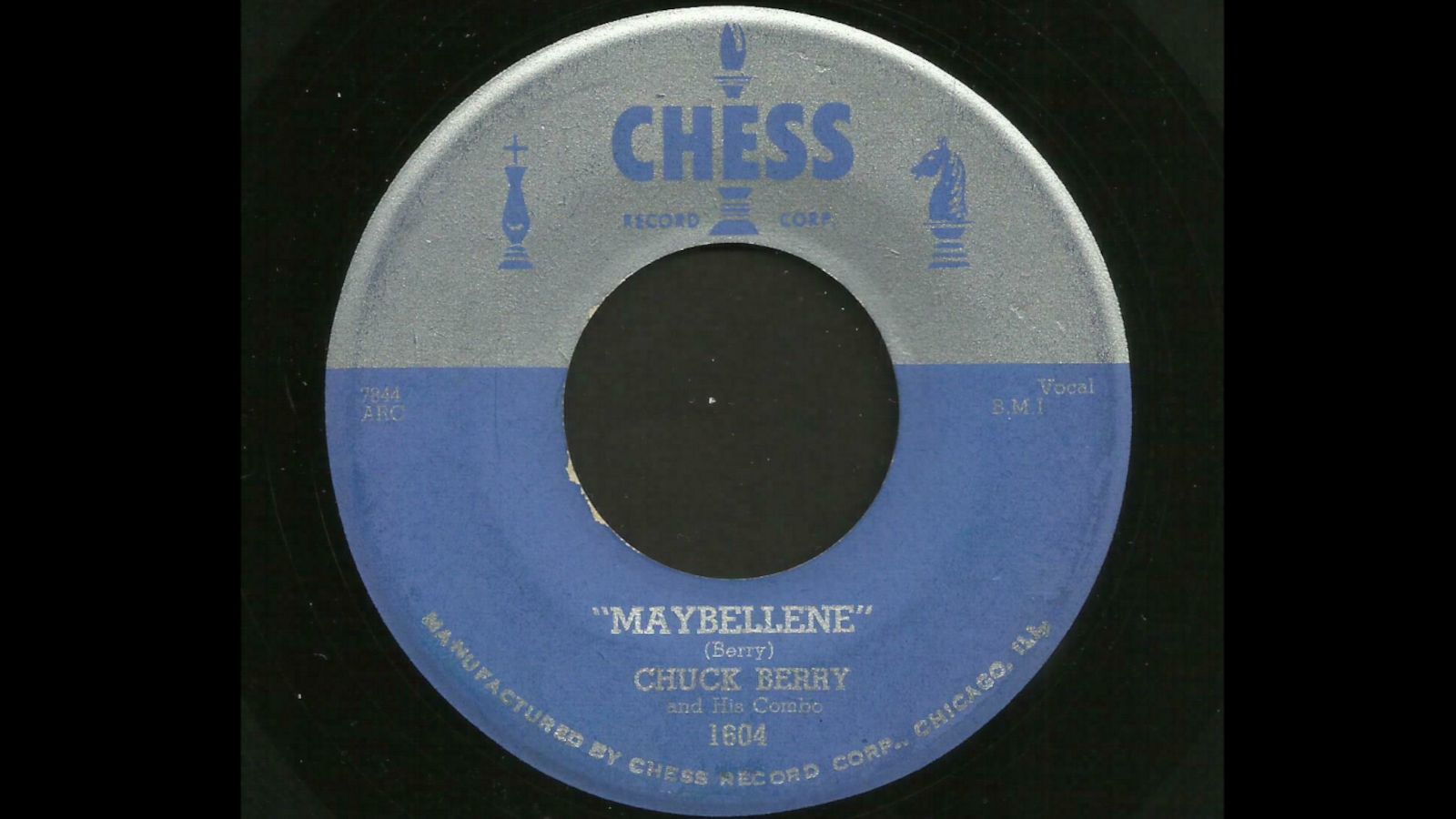

Chuck came back with his band and four new songs, including “Wee Wee Hours” and “Ida May.” The latter was a rocked-up number inspired in part by the traditional “hillbilly” tune “Ida Red,” made popular by Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys in 1938.

“And we set the band up, and we played all four of them,” Chuck said. He was sure “Wee Wee Hours” would be the song to clinch the deal, but Chess was taken by “Ida May” – except he didn’t like the title, which he considered too country sounding.

“And that was a problem, so nobody could think of a name,” pianist Johnnie Johnson recalled. “We looked up on the windowsill, and there was a mascara box up there with ‘Maybellene’ written on it. And Leonard Chess said, ‘Why don’t we name the damn thing “Maybellene”?’”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We looked up on the windowsill, and there was a mascara box up there with ‘Maybellene’ written on it

Johnnie Johnson

That suited Chuck, who changed the lyrics and took the songwriting credit.

The May 21, 1955, session features, in addition to Johnson, the trio’s drummer, Ebby Hardy, and blues giant Willie Dixon on bass. It took 36 takes to get the song recorded to everyone’s satisfaction. But considering it was Chuck’s first time in a recording studio, the session was an unqualified success.

Afterward, the guitarist went back to St. Louis and waited to hear what would happen with his song. Weeks went by with no word from Chess. Then, by chance on an August day, Chuck heard the record on the radio while passing by the tailor’s shop where he’d bought his high school graduation coat.

“I passed by the shop until the song played out, you know? I didn’t want anybody to see me listening,” he told NPR. “But it was ‘Maybellene’ I was listening to.”

When the song finished, Chuck ran the 20-some blocks home to tell everyone. “Knocked me out to hear myself, you know.”

Soon “Maybellene” was having the same effect on radio listeners.

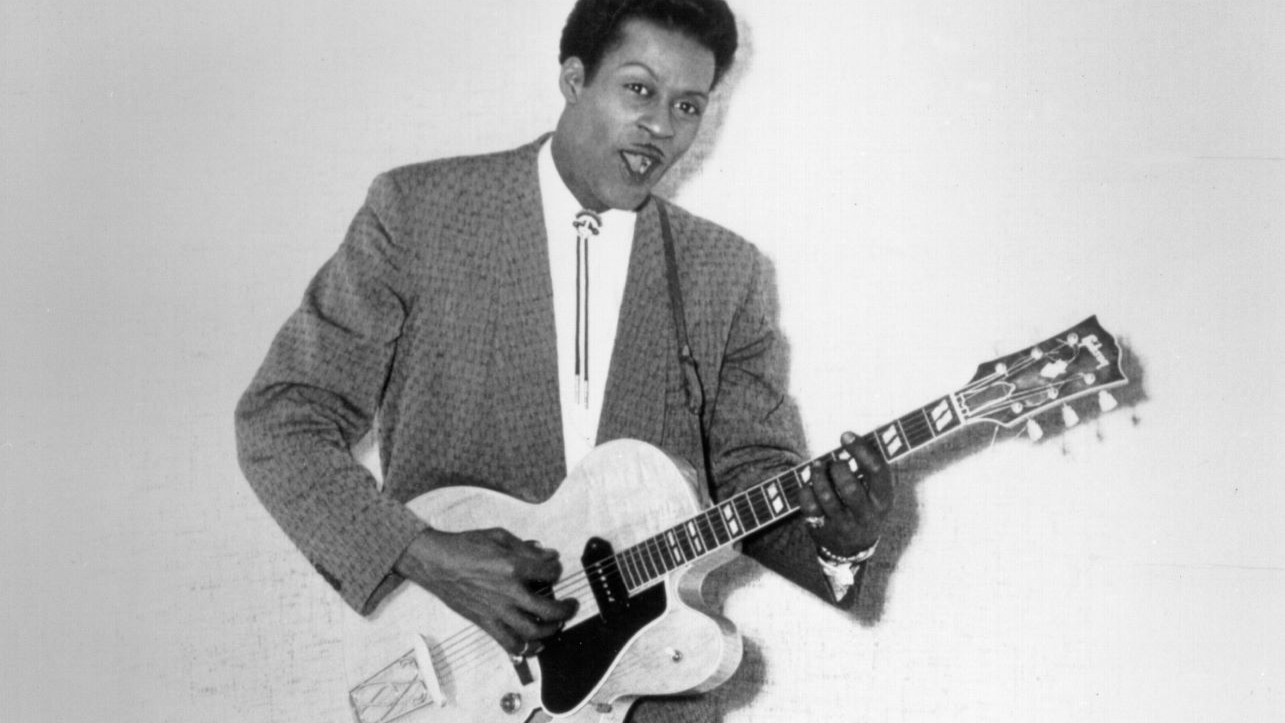

From the first bar, it was clear that this was something new. Chuck’s electric guitar is raw, energetic and infectious, relentlessly rhythmic and driving behind the vocal, then piercing through with heaps of his classic attitude in the solo.

The track featured Chuck’s modernized, up-tempo version of the T-Bone style with even more double-stops and string bends. What’s more, the song’s guitar sound was markedly different to the clean, chiming tones that came from Walker’s Gibson ES-250.

Chuck’s guitar, a Gibson ES-350T, drove his amp into distortion, adding a real sense of anarchy to the music.

With its combination of blues guitar and country stylings, “Maybellene” became a huge hit with record buyers of all races, hitting numbers one and five on the R&B and Billboard Best Sellers charts, respectively.