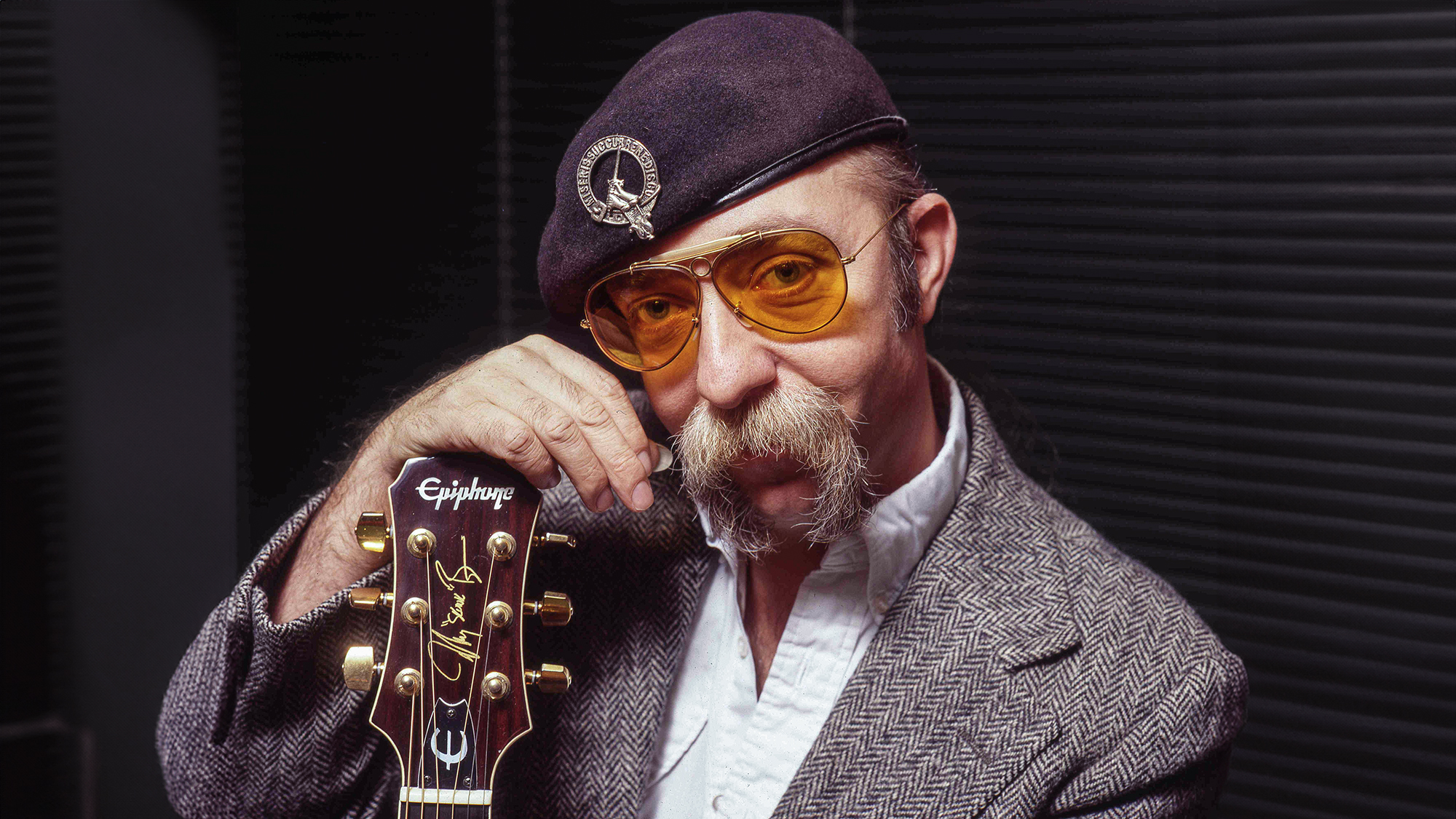

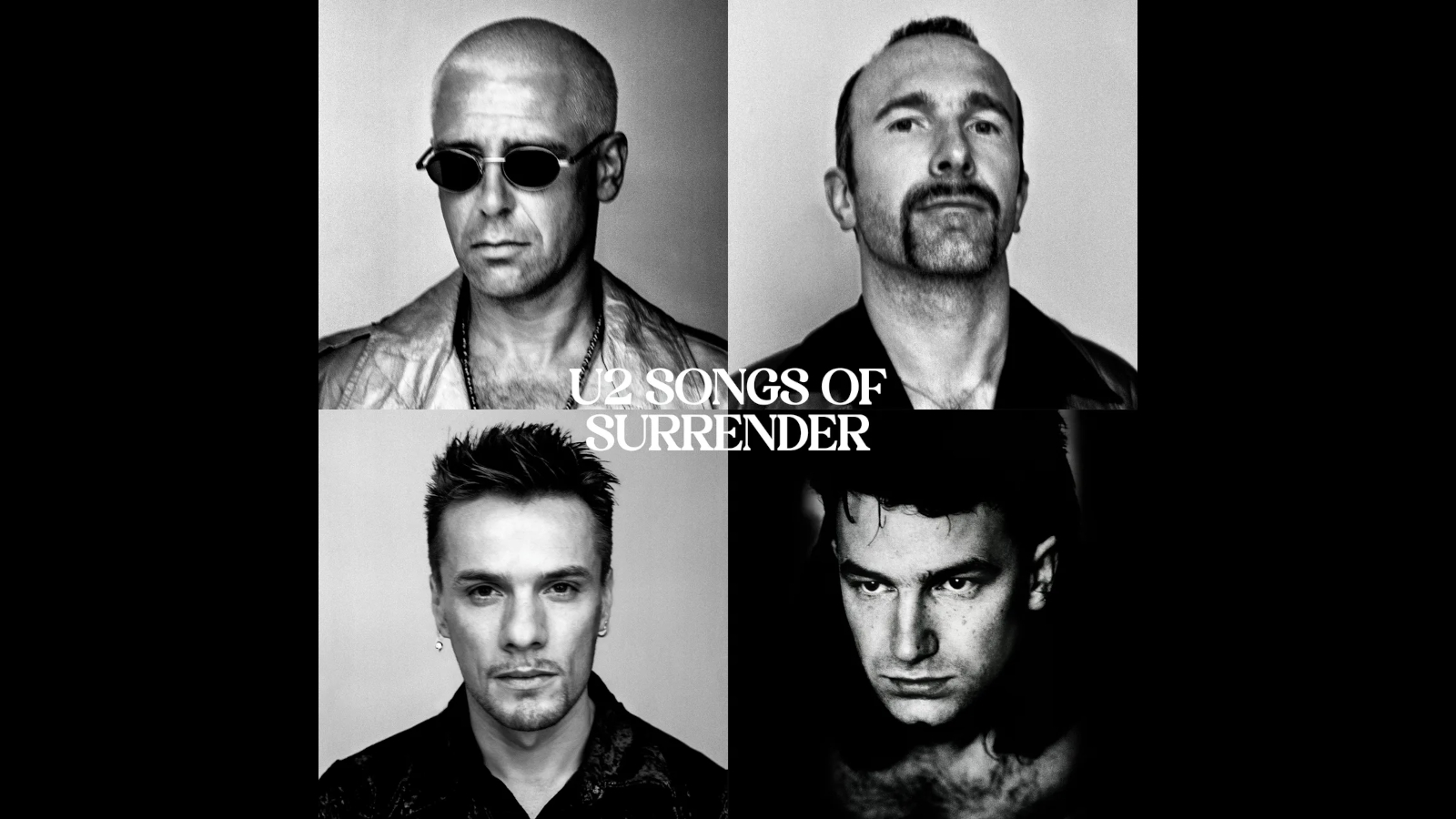

“There Were No Rules With This Project”: The Edge Reveals the Secrets Behind U2’s New Album, 'Songs of Surrender' – a Whopping Collection of “Reimagined” Songs From Their Back Catalog

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

During the course of their four-decade-plus career, U2 have been a daringly stubborn, forward-thinking lot, rarely repeating a proven formula, and constantly searching for the next big idea. Indeed, their momentum seems to have always been fueled by an almost Bowie-esque need for experimentation. Sometimes the gambits paid off spectacularly (the rich Americana textures of The Joshua Tree were traded for Achtung Baby’s postmodern European art-rock); other times, not so much (the techno dance-heavy Pop ranks as their most underappreciated effort).

But in each case, the band made it clear they weren’t running to stand still, and whether they delighted their fans or occasionally mystified them, their true measure of success was guided by their indefatigable quest for change.

And now they’ve really gone and done it. U2’s latest project – Songs of Surrender, a whopping collection of 40 “reimagined” songs from their back catalog – is one that will invariably provoke intense reactions, both good and bad, from their fans, many of whom regard the band’s original recordings as sacrosanct.

For The Edge, the driving force behind the four-disc set (he’s credited as producer, and he created much of the instrumentation), the notion of merely tweaking musical themes was one he rejected out of hand. Simply put, revisiting the past meant throwing a whole lot of it out the window.

“We’re not just treading lightly on hallowed ground. We’re going in with jack boots,” he says with a laugh. “That was our early decision: ‘Are we going to going to suspend reverence here and just go for it?’ And we decided to go for it, because we thought we’d get into more interesting territory if we gave ourselves that freedom.” He pauses, then smiles mischievously. “But we also had an overriding idea, which was to make intimacy the new version of punk rock for us.”

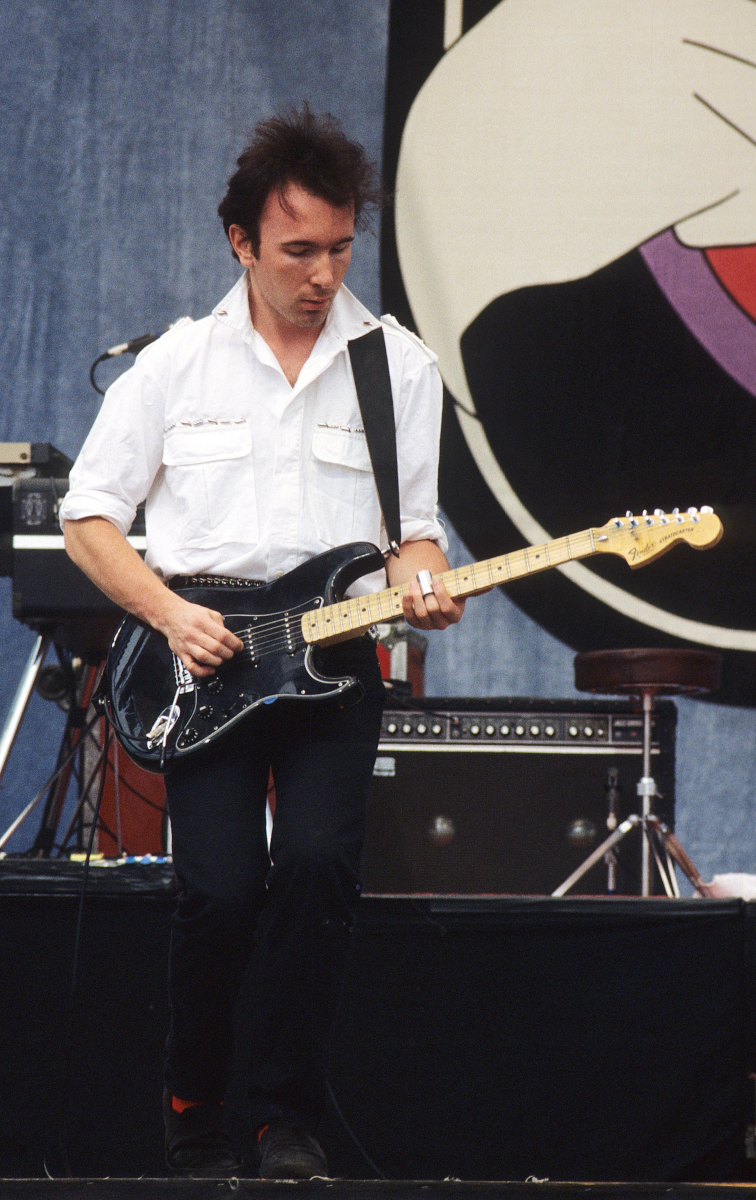

Punk rock in 2023, at least in The Edge’s world, is bathed in the lush sound of acoustics (for those thirsting for the guitarist’s ringing, soaring, effects-treated electric six-strings, adjust your expectations immediately). This is a softer, quieter, laid-back version of punk rock (and U2), and admittedly, it takes the ears a while to adjust.

The once anthemic “Pride (In the Name of Love)” is now stripped down, slowed down and sung by Bono in a lower register. It doesn’t so much confront you as it gradually seeps into your senses. Likewise, the youthful hormonic urgency of “11 O’Clock Tick Tock” now moves at a more mature pace, with The Edge performing a delicately plucked nylon-string solo in place of the original’s jarring electric lead.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

On some tracks, he dispenses with guitars altogether. The chiming electric rhythm of “Where the Streets Have No Name” is nowhere to be found on what is now a haunting hymn framed by synths and strings. Similarly, “Stories for Boys,” sung by The Edge and devoid of the guitarist’s cavernous leads, has been transformed from a surging rocker into an absorbing piano elegy.

Throughout most of the album, however, over minimal and sometimes no percussion at all, he’s briskly strumming and chugging away (and on a few songs, notably “Ordinary Love,” he demonstrates he’s an artful and creative fingerpicker), breaking down chordal and lead arrangements to their bare essentials. On cuts like “Sunday Bloody Sunday” and “Until the End of the World,” he performs virtual note-for-note versions of his famous solos, while on “The Fly,” now a slinky and sultry mood piece, he splashes twangy licks over a booming bed of bass guitars.

Our challenge was always to get to that guy at the back of the room, somebody who isn’t really a fan or isn’t paying attention

The Edge

Not everything gets a drastic makeover. “Vertigo” and “Desire” (here with heavily treated acoustics) still rock and swing as hard as ever, and in their new spare forms, they’re the best damn campfire songs around. For the most part, though, the emphasis is on reinvention, and each track brings with it a new surprise. The biggest revelation perhaps comes in the form of a question: Just why would a band so revered for its sense of grandeur want to reel it all in?

The Edge takes it on directly and thoughtfully. “It’s not something we’re famous for, because we grew up onstage in little sweaty clubs in America and Europe,” he says. “Our challenge was always to get to that guy at the back of the room, somebody who isn’t really a fan or isn’t paying attention. There was always an intense pitch to our music early on. So my thought here was, Let’s take minimalism to the nth degree, if it’s appropriate.’ And on a lot of these songs, it worked. We left just the bare skeletons of the original arrangements in terms of themes and hooks, taking things down to a really light touch.”

He’s keenly aware that “going in with jack boots” was going to be met with varying responses – and if anything, that appears to be the overarching point. “For this to be meaningful, we didn’t want to re-create something that was already out there and was well-recognized,” he says. “It was, ‘What happens when you take the band away and you remove from the mix everything we’re famous for?’ You allow the songs to stand on their own.”

You’re one of the most distinctive and copied players of the past 40 years. Usually we talk about some new wild sound you’ve come up with or a new pedal you’ve discovered. You’re not doing that here. [Edge laughs] Was that scary? Exciting? Both?

It was both. I mean, not scary, really. When we started this project, there was no expectation. We could have done a couple of weeks on it, and if we weren’t excited by the results, it never would have seen the light of day. As it happened, the more I got into it, the more excited I got. I thought, There really is something to this.

For me, the pivot was “Stories for Boys,” from the first album [1980’s Boy]. I hit on this piano approach that’s so different from the original. I sang a demo vocal of it and presented it to Bono, assuming he would do his own lead vocal. He said, “Edge, I love this! You should sing it, and let’s work on the lyrics to update it and give it a different twist.”

Because there was no pressure or expectation, and just through the sheer thrill of doing this, I think the whole collection has a kind of freedom to it, a lightness. I don’t think U2 fans have ever heard the band like this.

There is that old saying: “A good song is one you can play on an acoustic guitar.”

Yeah. Some of our producers have stressed that to us over the years, almost as an appeal. Steve Lillywhite would say, “Would you just play the song on an acoustic guitar? That’s how we’ll see what we really have.”

This collection sort of proves that if songs hold together, they really are indestructible

The Edge

Of course, that’s something we rarely did, but when we did it was useful. This collection sort of proves that if songs hold together, they really are indestructible. You can take huge liberties with that, and they’ll hold up.

There is some precedent for this with you guys. You and Bono played “Ordinary Love” and “Stuck in a Moment You Can’t Get Out Of” acoustically on TV shows.

We have. It’s interesting that some of those arrangements became the more iconic versions. “Ordinary Love” is a good example. “Every Breaking Wave” became a very big live song, and it was stripped right down to just piano and voice. That was really encouraging, learning that paring it back can be good for the song.

For this collection, can you pinpoint the moment when you said, “Let’s try this”? Was it literally you sitting at home playing a song on an acoustic that you had only played on an electric guitar?

There were a couple of moments. The great fun of this project was also trying to take some of the deep catalog songs that never became particularly well known and giving them a chance to shine. One of the moments of realization was “If God Will Send His Angels,” from the Pop album. It was a single, but we always felt as if we’d missed it. The problem wasn’t the lyric or melody; the flow of chords didn’t do justice to what Bono had done. So I completely re-arranged the chordal progressions, and now I feel like it’s a new song. It’s a better song. That was greatly encouraging.

With some other more obscure songs, I tested that idea. “Dirty Day” was one of the first songs I played on acoustic, and that’s a pretty nasty guitar-based tune on Europa – not a well-known song. I always liked its essence, and then playing it very simply on acoustic guitar, it really held up.

Some of the last things we did were the big classic songs. But even in that process, say, with “Pride (In the Name of Love),” I realized that the solo didn’t really make sense by stripping it back, so I kind of wrote an orchestral middle section to add some light and shade to the arrangement. There was a lot of fun there.

Was there a particular acoustic guitar that really guided your approach throughout the project?

I’ve been buying some vintage guitars, and some of them are absolutely amazing. Like these guitars from the ’40s are so pure and small sounding, but they’re so musical. That was a big revelation. Being so used to these big dreadnought guitars, I thought these smaller guitars had so much personality.

There was a particular guitar that was my go-to, a 1947 Martin 0-18, and it’s a beauty. I was with my son, Levi, in McCabe’s in Santa Monica. He was buying a pedal, and I was staring at this guitar in a case. I was like, “Mmm, do you mind if I try this guitar?” I instantly fell in love with it.

Also, I was trying to find ways to add other slightly more percussive sounds, so I dug an old hammered dulcimer out of the back of a closet. I’d never played it, so I was learning how to play this thing. That was a lot of fun.

I was talking with Melissa Manchester, who also re-recorded some songs from her catalog. She told me that one of her reasons for doing so was, after singing these songs for almost 50 years, she felt like she had grown into them. Did you have a similar feeling about your own songs?

Yes, I think that did happen. I also think that gave us the inspiration, in some cases, for new lyrics. The essence of the song felt more relevant from this perspective. Like with “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” when we got to the last verse, Bono said, “I think there’s a better verse here.” So now that song has a new final verse.

There was a particular guitar that was my go-to, a 1947 Martin 0-18, and it’s a beauty

The Edge

With the benefit of a bit of time from when that song was first inspired, from the safety of the peace that we now enjoy in Ireland, we could afford to be a little more direct. Without being overt, that lyric now addresses some of the history and incidents that inspired that song that we probably wouldn’t have felt comfortable addressing at the time.

You once told me that if you were having a problem writing a song, you’d crank up the effects and see where they might take you. Was it a challenge re-approaching the songs without those effects?

In most cases, I think I was able to use the musical themes from the original recordings, but I would abstract them. In the initial instance, we were probably struggling to find something with thematic power that would drive the song and support the vocals. Here it’s the opposite. It’s like, “How much can we take away?” It was less pressure, in a way. We were still being creative, but there was no sense that we hadn’t arrived with a song that couldn’t stand on its own.

I think we were maybe inspired by what we were all going through with the lockdown, where your entire life was reduced to the bare minimum. [laughs] It’s what we were doing with our song arrangements.

Obviously, you’ve played acoustic in the past, but here you’re laser-focused on it. As a player, did that present some new challenges from a technique standpoint?

Definitely. I was playing six-string, and I did some 12-string and some Spanish guitar. I played a beautiful old flamenco guitar that was made for me by Lowden. Yeah, I really had to stretch. But what it also did for me was, it gave me a real appreciation for the great acoustic guitar players, along with some of the techniques that I haven’t mastered. Certain picking techniques – I’m going to relish being a student again and becoming better versed in that. It’s a fascinating world. I don’t profess to be a master in these areas, but I’m such a fan.

I was struck by the songs you covered, but also some that you didn’t, like “Bullet the Blue Sky” and “The Electric Co.” Did you try them but you weren’t happy with where they went?

We didn’t do “Bullet the Blue Sky,” no. There were a few that, for one reason or another, we weren’t sure we found a new place. “Running to Stand Still” – I thought that it was already in a minimal form, so I didn’t know if we would find a new angle there. With “Bullet,” I don’t think we got around to it. I think maybe we felt that we’d already done so much from that album. We’d already gotten a few from The Joshua Tree. That was a dilemma, as well, not to overly concentrate on one or two albums.

Some were a challenge in a good way. “Beautiful Day” and “With or Without You,” we tried them multiple ways; we tried them very organic, and then, particularly “With or Without You,” we thought that we should go very abstract. That was a fun process.

When I heard about the project but hadn’t seen the track list, I thought, “No way will they do ‘The Fly.’ The original is such a gonzo, psychedelic electric guitar song.

[laughs] It is.

But you ended up doing it, and you turned it into a much darker piece.

The breakthrough with that song was, we decided that we wouldn’t have a lead guitar; we’d just have two basses, so Adam and I both played. The two bass performances come together to make this a very different version of “The Fly.” As you say, it’s kind of psychedelic, but it’s got a dark quality. I love it. Again, with the solos, it’s like, “What do you do with that?” The dulcimer came in very handy.

With some, I was happy to maintain the original ideas, but with others, it was obvious that something new had to happen

The Edge

On some other solos, however, like on “Till the End of the World” and “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” you do stick pretty close to how you originally played them.

Yep.

Did you try them another way first?

I don’t know. In those cases, I just felt that they were some of the key thematic ideas. Take “City of Blinding Lights”: We kept some of those big guitar hooks, but they’re now played in a different form. With some, I was happy to maintain the original ideas, but with others, it was obvious that something new had to happen. On “Out of Control,” a whole new solo idea spontaneously happened.

There were no rules with this project – that was the great thing. Bono kicked up a pretty serious media furor recently when he admitted that some of his early vocal recordings were a source of a certain amount of embarrassment for him. You can hear the strain in his voice. Mind you, it never even occurred to us in those days to lower the key to better fit his range.

Today, with each arrangement, we were able to go, “Where do you want to pitch this one?” I’ve got a similar vocal range to Bono, so I was able to take some good guesses for what would work for him. It was like tailoring the songs to suit him as a singer. At this point in his life, I think he’s a better interpreter of songs than he’s ever been. That was the ultimate goal: to serve the song by serving the singer.

You’re something of the ultimate gear guy. On this project, did you learn anything new about miking acoustic guitars?

Very often, I would do a quick initial acoustic demo at home. If I was in Dublin, I would be by the piano. And to my surprise, the engineers on occasion would go, “Whoa, that’s amazing. How did you get that sound?” I think it was because I had some really nice microphones. I found this one by Aston, an English mic that’s currently in production. It’s a very warm-sounding mic for acoustic guitars. Some of those recordings I made ended up on the album. It was that kind of project. Some of it was done in a proper recording studio in London, but a few were literally recorded in my bedroom.

Now that you’ve spent a considerable amount of time focused on the acoustic guitar, do you think you might go back to exploring new sounds on the electric with a fresh attitude?

I know the answer to that. [laughs] I’ve been working a lot on new guitar music, and I’m very excited about it. It’s at that prototype stage where… who knows? But the answer to the question is “yes.” I’m finding myself for the first time in a little while getting very excited about the electric guitar again. Maybe it’s something to do with the lockdown, having the time to not do very much. For me, that was such a creative opportunity.

Were it not for the lockdown, would you have done this massive acoustic project?

We’ll never know, will we? [laughs] We were due for some time off. We finished our last show in India in December of 2019. We came home, and almost immediately the world was turned upside down. That time would have been spent working on ideas and early-stage new songs. And we are. We have a lot of great material in the pipeline.

Order Songs of Surrender here.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.