“They were my go-to guitar players for a bunch of stuff... Whatever I thought of and asked for, they could do it”: How Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner transformed Lou Reed's moody, street-smart performances into an album of twin-guitar-led hard rock heroics

After Reed’s dark concept album, Berlin, bombed, guitarists Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner helped him get his groove back. The result was Rock ’n’ Roll Animal, the live classic that revitalized Reed's spirit and rescued his career

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The late Lou Reed took his walk on the wild side in 1972. But he didn’t become an animal – a rock ’n’ roll animal, to be specific – until the following year.

Recorded on December 21, 1973, before an audience at Howard Stein’s Academy of Music in New York City, Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal was no mere stopgap or contract-fulfilling release. In its definitive performances and forceful renderings of the material, mostly from Reed’s tenure with the Velvet Underground, it had all the conceptual integrity of a studio album.

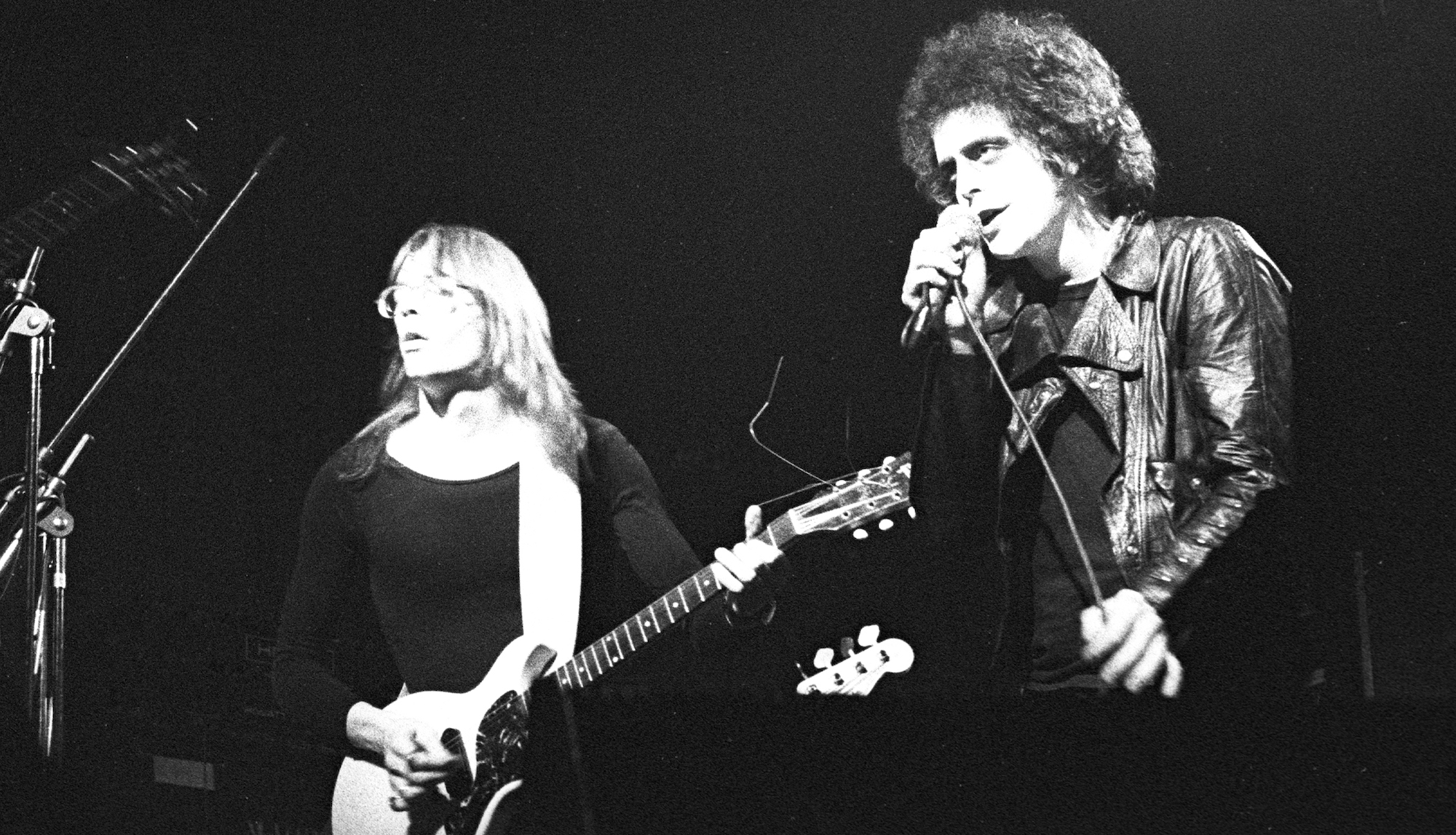

It documented an artist presenting his songs in a fresh manner, using the original versions as source material upon which to build and reinterpret, in this case with the help of an enormously potent band of genuinely animalistic caliber, led by guitarists Steve “The Deacon” Hunter and Dick Wagner.

And while the Allman Brothers Band’s At Fillmore East and the Rolling Stones’ Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out planted a flag for the live album as a legitimate artistic effort, Rock ’n’ Roll Animal and its Gold-certified success certainly deserves some credit for a mid-’70s spike that included breakthrough live releases for Peter Frampton, Kiss, Cheap Trick, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and others.

Rock ’n’ Roll Animal was also something of a career saver for Reed. While his third solo album, Berlin, would eventually come to be regarded as a seminal song cycle/concept album, its unrelenting darkness did not connect with listeners at the time. His label, RCA Records, heard no potential in it – certainly not as a follow-up to the previous year’s Transformer and its Top 20 hit, Walk on the Wild Side – and gave the record no support despite a Rolling Stone review declaring it “The Sgt. Pepper of the Seventies.”

Berlin was savaged by most critics, and even the burgeoning FM radio stations weren’t about to play its songs about heroin addiction. Released on October 5, 1973, while Reed and the Rock ’n’ Roll Animal band were near the end of a European tour, Berlin peaked at number 98 on the Billboard 200, some 69 points lower than Transformer.

There had even been plans to stage Berlin, initially conceived as a double album, as a musical, but those went unrealized as well.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I had my thoughts that if RCA marketed Berlin and put a single-edge razor blade in the cellophane, it would probably have done better,” cracks Steve Katz, the founding guitarist of the Blues Project and Blood, Sweat & Tears, whose brother Dennis was managing Reed at the time. It was this connection that would lead to Katz producing Rock ’n’ Roll Animal.

“Lou and I had gotten friendly, and he was starting to rehearse for a tour,” Katz recalls. “He said to me, ‘What do you think I should do? Berlin is really a commercial bomb.’ I said, ‘What you ought to do is put a great live band together and do Velvet Underground songs and do it in a not heavy metal but hard rock kind of way. That way you’ll get to the audience that hasn’t been exposed to the Velvet Underground stuff.’

“He said, ‘That’s a great idea. Would you produce it?’ ‘Are you kidding? I would love to.’ And we went from there.”

They were my go-to guitar players for a bunch of stuff. Their versatility and their amazing, innate musicality… Whatever I thought of and asked for, they could do it

Berlin producer Bob Ezrin on Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner

So much of Rock ’n’ Roll Animal’s success was about the band, which also included bassist Prakash John, drummer Pentti “Whitey” Glan, and keyboardist Ray Colcord. But Hunter and Wagner were the stars of the show.

They had been brought to Reed by producer Bob Ezrin for Berlin, where they joined such musical luminaries as Jack Bruce and Tony Levin on bass, David Bowie’s Aynsley Dunbar and Procol Harum’s B.J. Wilson on drums, Steve Winwood on organ, and brothers Michael and Randy Brecker on horns.

Hunter and Wagner both boasted Midwest roots: An Illinois native, Hunter was part of Mitch Ryder’s band Detroit, whose sole, self-titled album was produced by Ezrin and featured a hard-hitting reworked rendition of the Velvets’ Rock & Roll. Iowa-born Wagner established his reputation in southeastern Michigan with bands such as the Bossmen and the Frost, and later in New York with Ursa Major.

Ezrin used both players on Alice Cooper’s 1973 album, Billion Dollar Babies, and they’d become part of the Welcome to My Nightmare team after the original Cooper band broke up. They’d also be tapped as a kind of “fix it” team on Aerosmith’s Get Your Wings, most notably playing guitar solos on the group’s rendition of Train Kept a Rollin’.

“They were my go-to guitar players for a bunch of stuff,” Ezrin recalls. “Their versatility and their amazing, innate musicality… Whatever I thought of and asked for, they could do it. They were so adaptable, and very inventive. They were great collaborators. So it was natural to go to them for the Berlin record.”

Hunter was the primary player for Berlin, in fact. “In many of the songs there was kind of a blues bed – it felt like a blues bed to me – and Steve was at that point my favorite blues player who was also a rock and roll player,” Ezrin explains.

“I knew there would be a lot of soloing and stuff, and Steve is a great soloist. Not to say that Dick isn’t; he is, but [Wagner’s] style and taste was more rock grandeur. That was very useful to me on some songs, but on other songs it didn’t fit. So I had Steve on pretty much every track and Dick on certain tracks.”

Though rocked by the initial failure of Berlin – and dealing with acknowledged substance-fueled PTSD from the experience – Ezrin was heartened to see Reed bring Hunter and Wagner into his touring band.

“Having the two of them together was perfect,” he says. “They covered all the bases.” For Hunter, meanwhile, it was a chance to get to know Wagner, who, despite their Detroit roots and many common colleagues, he’d “only met kinda briefly, maybe a year before,” he says, having recorded separately on Billion Dollar Babies and Berlin.

Wagner – who passed away in 2014 at the age of 71 – said some years later, “It was pretty easy playing with Steve. I didn’t really know him well before [the Reed tour], but I knew who he was. And when we got in a room it was really easy to play together. There wasn’t a lot of talking or planning; we just started playing and fell in very naturally with each other.”

Via Zoom from Spain, where he now resides, Hunter adds, “I really got to know Dick and work with him more on that tour, which wasn’t really called the Berlin tour; it was just a Lou Reed tour. The first six, seven days of rehearsal we never even saw Lou. We got a list of songs he wanted to play and, of course, tapes and stuff to learn the songs.”

Working parts out with Wagner was easy, Hunter explains. “When Dick and I started working, honest to God, it didn’t take a lot of work. I would play one thing and he would play the opposite or something else that fit. A lot of the arrangement ideas were Dick’s. He was good at that sort of thing and could work things out really quickly. There were lines we played in harmony, of course. We worked those out, and we made sure we both played the same number of solos. There wasn’t much else to work out, really.”

For that matter, the entire band seemed a perfect fit. “When we got together and played for the first time in rehearsal,” Hunter says, “you could sense, ‘Oh, wow, this can be a really powerful band. These are all great players. This is gonna be a lot of fun.’ You sort of noticed that right off the bat. Lou’s material is so powerful, as everybody knows, and I think we felt our job was to make that power and angst come out of the music so that Lou could ride on top of it. We really wanted to make it just slam. That was our goal from the beginning.”

The group worked on its own for most of the rehearsal process, Hunter says, with Reed coming in “when we reached a point where we thought we were ready for Lou to hear us. He came in and sang each of the songs to get a feel. That only took a couple of days, and then we were on the road.”

Katz had become friendly with Wagner when the guitarist auditioned for Blood, Sweat & Tears. He was well aware of the potential for both the band and the Hunter-Wagner team.

“They were great,” he says. “I think what made them so good is they were really great Les Paul players. If you’re a guitar player, you know what I mean. The Les Pauls have sustain and midrange, and that worked really well for the songs they were playing with Lou.”

There was a story behind Hunter’s 1959 Les Paul TV Special, however. His Gibson SG and Ezrin’s Martin acoustic were stolen from the Record Plant in New York City while the two were on a dinner break during the Berlin sessions. “Someone had finagled their way in and said, ‘I’m here to pick up a couple guitars,’” Hunter recalls. “Someone let ’em in and they picked up our guitars and walked out.”

The studio’s insurance paid for new instruments, and Hunter found his replacement at a store in midtown Manhattan.

“It was terrifically ugly, but in a good way,” he says with a laugh. “It was real ugly yellow. It had one pickup, a P90. I plugged it into a Bassman and played it and just fell in love with it immediately. I had the cash from the insurance and just bought it on the spot. I loved playing it and used it till the neck broke, unfortunately, which was common with a lot of those Les Pauls.”

For the tour rig, Hunter plugged into a 50-watt Hiwatt amplifier with a 4x12 cabinet, and went light on effects, using just an MXR Phase 90 pedal.

“Somewhere along the line I picked up an Echoplex, but there were no distortion pedals or anything like that,” Hunter says. “I don’t like them. I didn’t use any kind of booster pedals or fuzz or anything like that. Didn’t need ’em.”

Reed’s shows during the fall and early winter of 1973 featured plenty of Berlin — up to five songs each night, including at the shows recorded for Rock ’n’ Roll Animal. But arguably the most memorable and signature piece of each performance was the instrumental introduction Hunter composed to open the show, a majestic three minutes and 20 seconds that wove together elements of blues, jazz, prog, and even Southern rock into an overture that morphed into the VU’s Sweet Jane.

Hunter had started working on the piece a few years before during his time with Ryder and Detroit.

Working on stage with him, Lou was a pro. I never felt uncomfortable onstage at any one time, ever, with Lou

Steve Hunter

“I never got very far and kept putting it on the back burner. I almost threw it away a couple times,” he says. He built it to a point where he could use it during a short tenure touring with the Chambers Brothers, but even then Hunter says, “it was still going through changes. I thought it was just an exercise or something, maybe, and again I put it on the shelf and forgot about it.”

He returned to it again during rehearsals for the Reed tour, when it was suggested that some type of instrumental introduction to bring Reed onstage would be useful.

“We played around with some things,” Hunter recalls, “and I happened to say to Dick, ‘I’ve got this piece. Maybe we can jam to it. I’ve got parts for it, melody and things. See what you think.’ I showed it to the band and we played it down and it sounded fabulous, the best it ever sounded. When these guys played it, it sounded amazing. I tried playing it after that and it never sounded that good.

“When we toured in Europe it ended up being the intro to Vicious, 'cause Lou wanted to start the show with that. Vicious was in E minor, which fit, because my intro ends on B major. When we came to America he wanted to open with Sweet Jane. And Sweet Jane was in E, so it all worked.”

When Katz heard what the band was doing, he knew it was gold.

“Sweet Jane was already this incredible song [Reed] had written, and thanks to Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner it became a classic,” Katz notes. “That overture really set up the whole album, and I think that’s exactly what I wanted to hear – the band taking these songs and doing a different slant on them with the guy who actually wrote them.”

Kevin Hearn of Barenaked Ladies, who was part of Reed’s later bands from 2007 on – including one lineup with Hunter – says Reed remained fond of the Sweet Jane introduction and even put it back into his concerts, as an encore, at the suggestion of his other musicians.

“Lou really loved that idea,” Hearn says. “It’s not something he considered a relic of the past or anything like that. He very much enjoyed it, and we worked on it in rehearsals.”

Hunter, however, was strong-armed into surrendering his composing rights for the U.S. edition of the album and would not receive any songwriting royalties for his Intro until 2011, even though he had been part of Reed’s Berlin Live Tour, playing the entire album during 2007 and 2008.

The 1973 tour was initially a rough-and-tumble affair, during which Reed performed with his face painted white. Addled by drugs and personal issues – he had divorced his first wife, Bettye Kronstad, that fall after just months of marriage – the singer delivered performances that “were either brilliant or terrible, depending on how stoned he was,” according to biographer Victor Bockris.

Reed hit bottom in Brussels when he left the stage after just a half hour, causing a riot at the venue. Afterward, he maintained his composure, even reportedly decreasing his substance intake, and was in more consistent form when the group returned to the U.S.

Nevertheless, Hunter contends that “working on stage with him, [Reed] was a pro. I never felt uncomfortable onstage at any one time, ever, with Lou. Ever. He’s an artist, and you just get used to the way that he performs. You just adapt to it. That’s what you’re supposed to do.”

Katz, however, feels “there were two Lous. When we first met, he wasn’t on drugs that much. By the time Rock ’n’ Roll Animal came around, Lou would either be on speed or coming down from it. He was actually more fun to be with when he was taking speed. When he was coming down, he was impossible.”

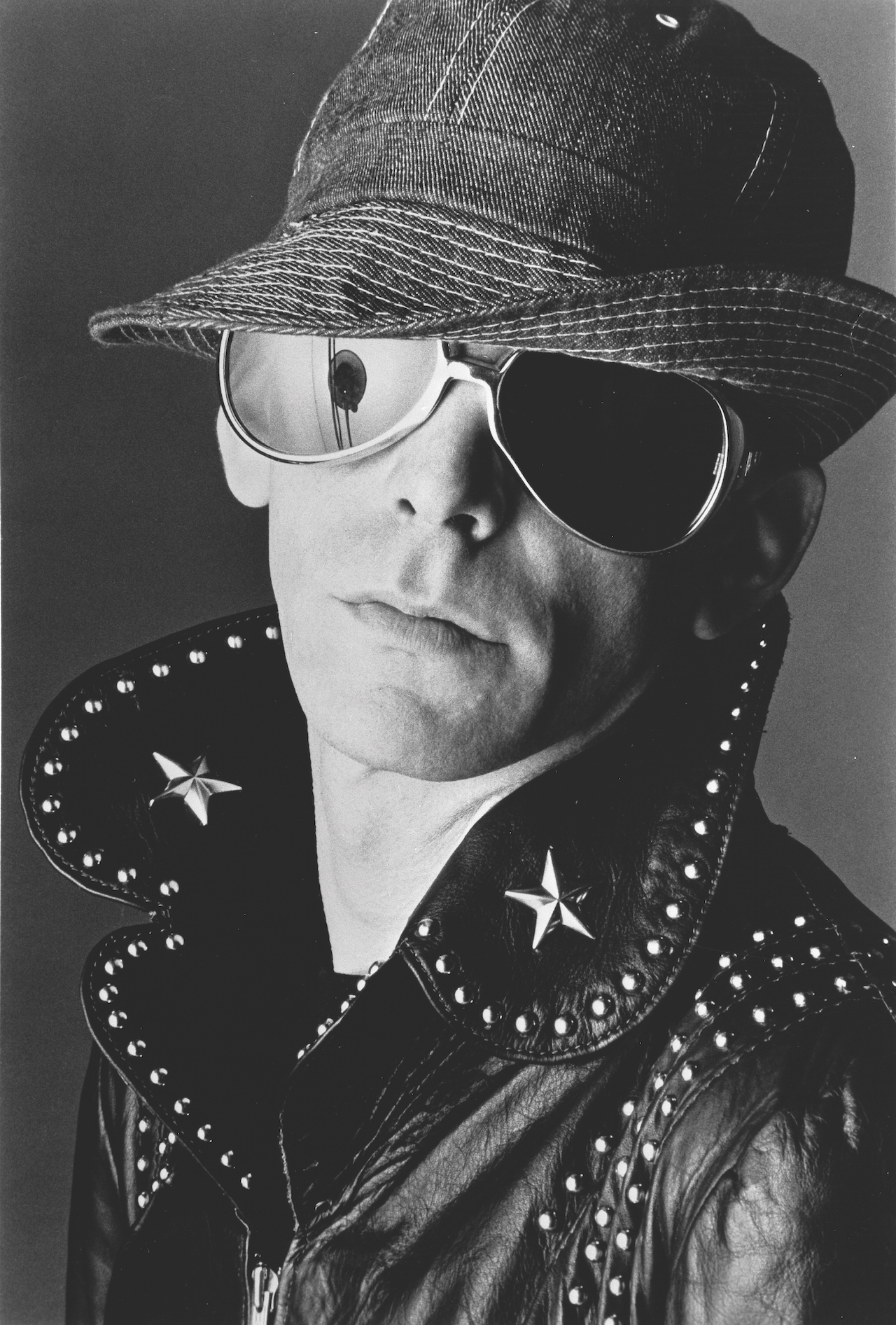

Reed’s two concerts at Brooklyn’s Academy of Music followed the set list the group had established, consisting of mostly solo material from Transformer and Berlin plus five Velvet Underground songs. He did, however, surprise his stateside fans with a new look.

Having begun the tour with bushy hair, he’d cropped it shortly before arriving in the U.S. He also began wearing black mascara and lipstick, and studded S&M-style wristbands.

“I thought it was ridiculous,” Katz remembers. “He comes out looking like a speed freak and dressing like a speed freak and acting like a speed freak. Thank God the album didn’t come out as a video.” Katz also recalls that “Lou’s singing wasn’t that great” but it was honest, and the band mitigated any number of shortcomings.

“Because the band was so good, Lou could be however he was, and it would make sense,” says Katz, who listened from the Record Plant’s mobile recording truck. “He’s the guy that wrote all this stuff, so how his voice sounds doesn’t make much of a difference. The trick was to make sure his persona came through, along with the band.”

The recording itself was smooth, save for a malfunctioning audience microphone that forced Katz and the engineers to fill in applause and cheers from an unlikely recording.

“We were at RCA Studios, and our engineer [Gus Mossler] went next door to the archive room and pulled out an audience track, the first one he found. I said, ‘Oh, this is great. What is it?’ He said, ‘It’s from a John Denver concert.’ I laughed my sides off, and we put it in. I never told Lou.”

Because RCA was in a hurry to recoup after Berlin’s failure, it green-lighted a single-disc album, even though the show had enough material for a double LP. With just five tracks, Rock ’n’ Roll Animal concentrated on the VU songs that were Katz’s focus in the first place, with the 13-minute-plus opus of Heroin and a similarly epic 10:15 treatment of Rock ’n’ Roll as standouts alongside Sweet Jane.

Lady Day was the only Berlin track included on the album, although a CD reissue from 2000 added Caroline Says I and How Do You Think It Feels. More songs from the shows came out two years later on Lou Reed Live, which Katz also produced along with Reed’s next studio album, Sally Can’t Dance, in 1974. Going through his own divorce at the time, Katz surrendered his royalties for both of the live sets, which he now calls “probably the stupidest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

In the end, Rock ’n’ Roll Animal was as triumphant as Berlin was disappointing. It hit number 45 on the Billboard 200 and became Reed’s first Gold album. The reviews were largely positive: Rolling Stone declared it “very fine” and “a record to be played loud,” while the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau called it “a live album with a reason for living.”

There were contrary opinions: A pre-Pretenders Chrissie Hynde castigated Reed’s appearance in a review for Britain’s New Musical Express – the publication that retrospectively took Reed to task in 1979 for “wrecking the rare beauty and affirmation of his greatest songs by turning them into cliché-ridden hack heavy metal mutations.”

Fifty years on, however, Rock ’n’ Roll Animal is roundly considered in a kind light. Even Berlin has enjoyed reconsideration as part of a golden, if provocative era – as if there were any other kind in Reed’s lengthy career.

“I loved it,” Ezrin says of Rock ’n’ Roll Animal. “I was so happy and proud that people I admired, enjoyed working with, and had such deep affection for found each other and did this work. I thought it was – and still do think – it’s amazing.”

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.