"It’s not what you play, it’s what you don’t." Paul Rodgers – the singer's singer who played with the guitar player's guitar players – on what he learned from the likes of Paul Kossoff, Mick Ralphs and Jimmy Page

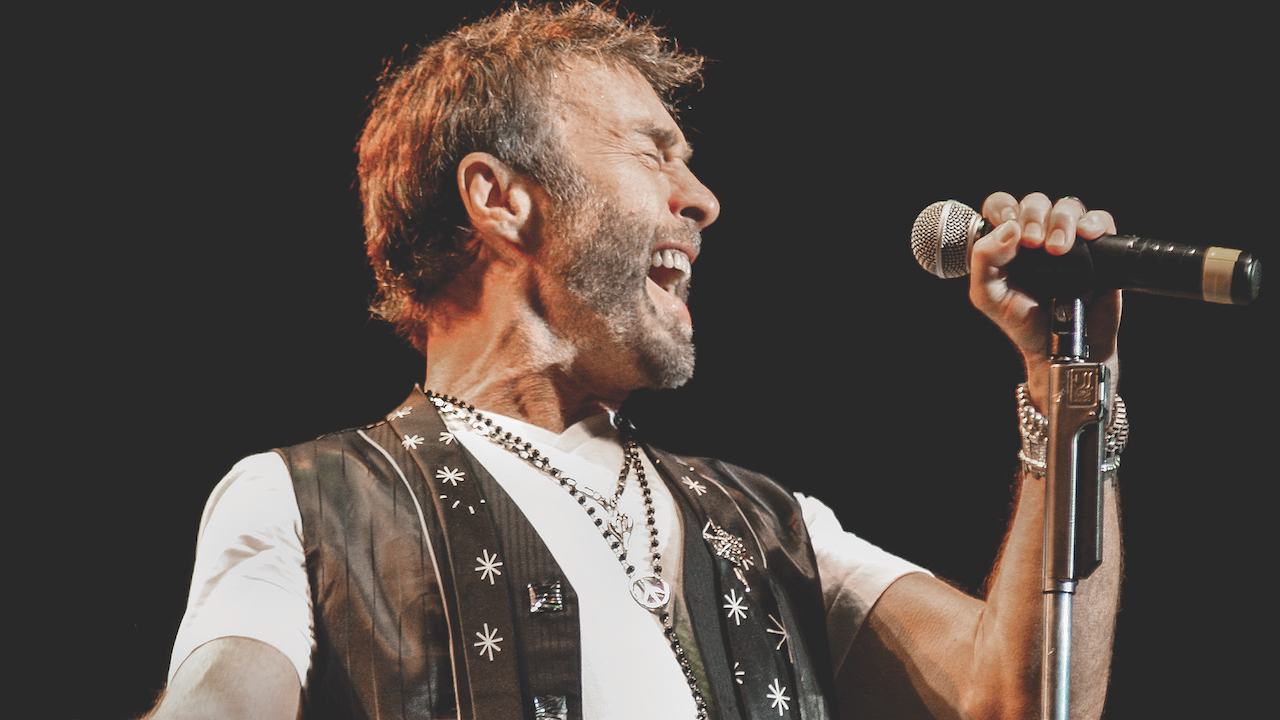

As the lead singer of Free, Bad Company, and the Firm, Paul Rodgers is hailed as one of the greatest vocalists in music. He’s the singer’s singer, with fans that include Robert Plant, Rod Stewart, Bryan Adams and Chris Robinson, to name a few.

Inspired by the likes of Otis Redding, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin, Rodgers has put his rich and vibrant voice to use on timeless hits like “All Right Now,“ “Can’t Get Enough,” “Feel Like Makin’ Love,” “Shooting Star” and “Rock And Roll Fantasy.”

While his place in the pantheon of greatest vocalists of all time is assured, Rodgers is less celebrated for his accomplished and underrated guitar work. After all, he crafted the bruising riffs on “Rock Steady” from Bad Company’s self-titled 1974 debut, and played the exquisite acoustic guitar textures that frame “Seagull” and “Crazy Circles.”

He also laid down the lead guitar on “Rock & Roll Fantasy,” the harmony lead solo on “Can’t Get Enough” and the solo on the Firm’s “Radioactive.”

As with his singing, Rodgers’ guitar playing favors economy over flash, and swagger and soul over studied technique.

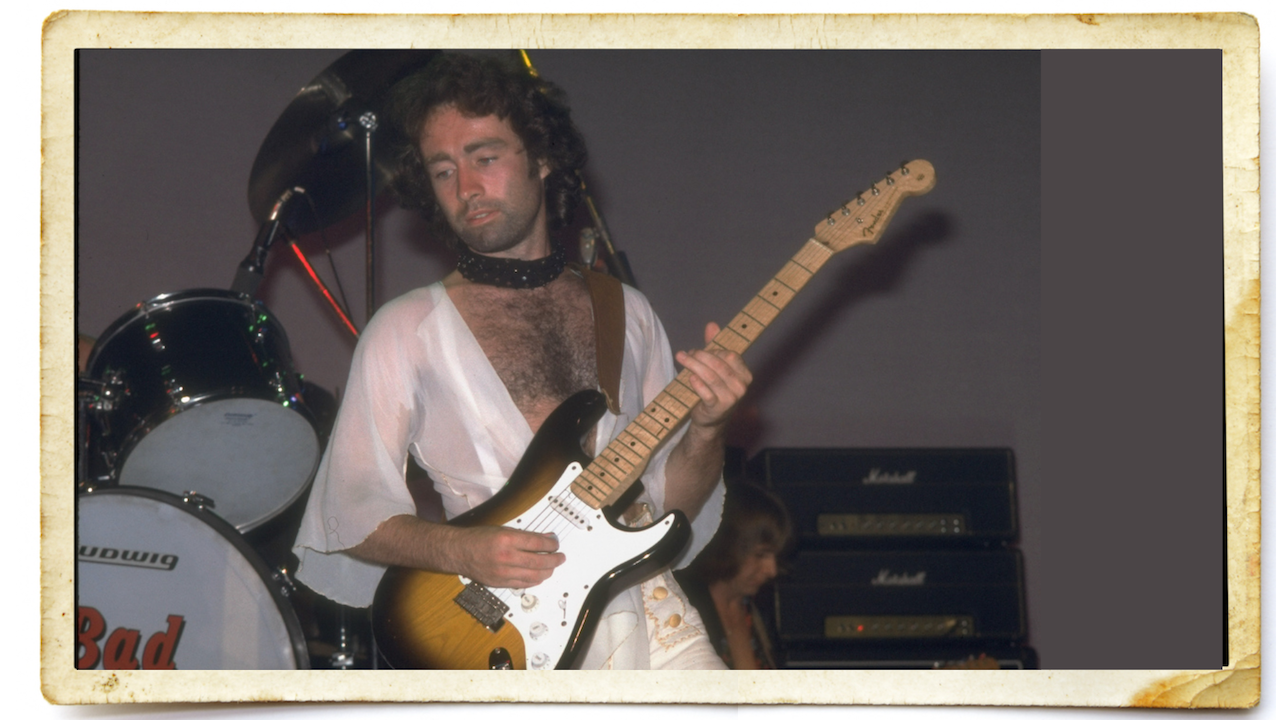

Through the years, working alongside Paul Kossoff in Free, Mick Ralphs in Bad Company, Jimmy Page in the Firm and Brian May in Queen, Rodgers has partnered with his share of rock’s elite six-string slingers and can lend witness to their creative brilliance. Despite this, he remains modest about his guitar playing.

“Well, I have to be humble, because I’ve been in such amazing guitar company,” he tells Guitar Player when we catch up with him. “When you look at the guitarists I have played or sang with — whether it’s Paul Kossoff or Jimmy Page, Mick Ralphs or Jeff Beck, Brian May or Neal Schon — they’re amazing people and amazing personalities.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But the 74-year-old’s days as a rock and roller nearly came to an end a few years ago. He suffered a stroke in 2016. It was followed by 11 minor strokes and another major stroke in 2019 that left him unable to play guitar or sing.

Surgery and therapy saved him, but as his wife, Cynthia Kereluk Rodgers explains [see below], it was ultimately the guitar that gave him back his spirit, not to mention a new release, Midnight Rose, his first new solo album of original material in almost 25 years.

The record was made with guitarists Ray Roper and Keith Scott, bassist Todd Ronning and drummer Rick Fedyk, with additional assistance from onetime Allman Brothers Band pianist Chuck Leavell, among others. Notably, Midnight Rose has been released on Sun Records, the legendary label that was home to Howlin’ Wolf, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins, among others.

For Rodgers, who found his calling through classic rock and roll as a youngster growing up in North Yorkshire, becoming a Sun Records artist is a bit of a pinch-me moment.

“My experience with Sun Records was Howlin’ Wolf and Elvis Presley,” he explains. “My best friend across the road up in Middlesbrough, we sneaked his older brother’s ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ record out and put it on the player. It comes on and I’m like, Wow! I’m still sort of starstruck, to be honest.”

Midnight Rose is your first record of original material since you released Electric in 1999, almost 25 years ago. What led to it?

During the pandemic, I was sitting at home, just noodling about with an acoustic guitar, and I thought, Well, I’m just going to pull all the songs I’ve got and see what I have. I had quite a bunch, so I got the guys together and we went in the studio to see what we could do. We did “Coming Home” first, and to see everybody and make eye contact while cutting a track was just wonderful.

When did your health problems begin?

About the same time. It was almost as if God said, “Okay, you! There’s a slap round the back of the head. Wake up and do something!” And that’s what I did. It was very humbling to be in hospital and down for the count. You get to rethink everything and think about what life’s all about, and do something worthwhile. So that’s what I tried to do.

Quite a few songs on the album are infused with a sense of spirituality and mortality. Was that lyrical thread inspired by your health issues?

Yes. I always was interested in meditation, way back in my hippie period, when George Harrison got into the Maharishi and meditation. I meditated all the way through Free, Bad Company, the Firm and Queen. It always centered me and kept me balanced. I called on that strength, that spiritual aspect of life very much during my hospital period.

And music was very therapeutic. It has been, because that’s all I’ve ever done — just follow the music and see where it takes me. And it’s taken me from my little hometown in Middlesbrough all the way around the world many times. And it still takes me on a journey, and for that I’m very grateful.

On “Melting,” the lyrics are powerful, touching on the emotional struggle that you were going through.

Well, yeah, I think it’s the blues influence — John Lee Hooker and that kind of thing. I came up with the riff, first of all, because I like to leave notes ringing that will harmonize with the next note. I’m playing acoustic on the record, and the lyrics just kind of flowed out.

“Highway Robber” taps into your fascination with the outlier, the outlaw life, and that goes back decades, starting with Free, and then with Bad Company.

All my life I’ve been a bit of a rebel, all the way back to school. I’ve always felt a bit of an outsider, and I feel a great rapport with outlaw kinds of figures, especially in the Wild West — such a lawless, wild country that is finding its way in the world. I’m influenced by that.

What was your first guitar?

Well, my father — we call him “my old man” in England — bought me an acoustic guitar. I can’t remember what it was, because I knew nothing about guitars. He handed it to me and said, “There you go, son!” and that was it. He didn’t say where he got it from, why he had it or anything, but that made me eligible to join my school class band. Any instrument you had, you’re in the band.

Different people came and went, but four of us stuck it out. I became the bass player, because I sold my acoustic guitar and bought a Vox Bassmaster. I actually got a copy of it, in my later years. It’s nice to have and it’s really beautiful.

What musicians inspired you?

Well, I think that experience set me on the path to music. Rock and roll got really big, and the Beatles turned up, and then it really exploded. In the course of listening to the Beatles, I discovered the blues, and my fellow bandmate, Colin Bradley, who was a singer and guitar player, showed me the 12-bar blues, which I really took to. I thought, What a magical structure it is!

There are millions of songs already written on it, and you can still write a million more. It’s so handy, because it means any bunch of guys can get together and do a 12-bar. It’s very versatile.

Who was the first guitar player that blew your mind?

That would be Jimi Hendrix. I saw him on a TV show called Scene at 6:30 when he wasn’t famous at all. Pete Murray, a DJ, introduced him and said, “Here he is, Jimi Hendrix!” And he held his arm out and the camera cut to Jimi and the guys in the Experience, and they went into “Hey Joe,” and it just blew my freaking mind!

There was this guy with this great big hair, and he had a wonderful song, which was really bluesy, and he played amazingly. Then he lifted the guitar and started to play the solo with his teeth. Fuck, it just blew my head off, really.

Did you ever see him live?

No, not really. When I was with the Wildflowers in Finsbury Park and Jimi was just starting out as the Jimi Hendrix Experience, there was a pub down the road that had gigs in the upstairs room. It was the height of summer and they had all the windows open, and Hendrix was playing there, but we couldn’t afford to get in.

All of a sudden, a cab pulled up and out jumps Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, and then another cab pulled up and out jumps Hendrix himself in full regalia — hair and vest, the beautiful clothes he used to wear — and everybody was just blown away.

All of a sudden, a cab pulled up and out jumps Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, and then another cab pulled up and out jumps Hendrix himself in full regalia

He walked through the crowd and up the stairs and started to play. That’s as close as I got. We could hear him, but it wasn’t the greatest sound because it was coming out the windows and there’s a whole audience inside soaking up the sound.

But, yeah, we heard him, all right.

Who was the first guitar hero you saw live?

Peter Green with Fleetwood Mac at the Marquee. Very impressive indeed, because he would sing as well, and he had Mick Fleetwood on the drums and John McVie on bass. Brilliant.

Peter Green used to sing, and then he’d look at the guitar and he’d play a phrase to answer himself, and then he would look down again and he would just alter the tone fractionally, and play another phrase.

Every phrase was unique, and it was so amazing to watch him.

You were starting to find your voice as a singer even before Free and continued pushing forward with guitar.

Yes. The Beatles were writing their own songs. Songwriting and playing is a thing you had to do, and songwriting was very much to the fore for me. So I found acoustic guitar was very good to work with because, in the little bedsits I inhabited, you could not play an electric guitar at any volume level at all. The first song I wrote was “Walk in My Shadow.” That was on the first Free album [1969’s Tons of Sobs], and that was my first foray into writing acoustically for electric.

Leaving space is part of your signature as a singer. I also hear that economy in your guitar playing. Was that way of playing an adjunct to your singing voice and translating when you would play guitar?

I think it was very much so, because I learned economy of notes from listening to great singers like Ray Charles and Aretha [Franklin]. You know, they don’t overdo it. I try to bring that economy into my playing. That was the whole basis of Free. Alexis Korner was our mentor. He was like a father figure for us, because he was an old jazz guy and he was really wise. You’d go to him for advice, and he did the same thing with the Stones. He taught me a lot of things.

Economy of notes is something that he stressed: It’s not what you play, it’s what you don’t. That’s something that comes naturally to a band like Bad Company. What you need to remember is the instrument you play, whether it’s guitar or voice, is a vehicle to express an emotion. It’s not to prove how clever you are on an instrument; it’s knowing how to deliver an atmosphere and a mood.

The point is to put across what you’re saying, and you don’t really put that across by playing too much. You put that across by delivering the emotion, and then you leave the space for the listener.

“All Right Now” is one of the most enduring songs in the classic-rock universe. How did you and Andy Fraser come up with it?

We used to always play [Albert King’s] “The Hunter” and we could not get off the stage, especially in Newcastle, without doing it. I said to Andy, “We need a song that’s at least sort of as good as ‘The Hunter,’” because we were trying to do all our own music and have a voice and be an entity that wrote its own songs and had its own message.

So I said, “We’ve got to have something really simple like [sings] ‘All right now.’” And then I said, “Maybe that’s it! Let’s work on that as the chorus.” Andy took that away and came back with all the big arena chords. And I thought, Okay, I’ll write the rest of the lyrics to this.

My thought process for that song was, something’s been going on and now it’s all right. So what’s been going on? Well, a guy meets a girl in the street: [reciting lyrics] “There she stood in the street.” What was she doing? She was “Smiling from her head down to her feet.” And the lyrics just flowed out from there. We did it that night and it was a monster, straight away.

In the studio, every member of the band really contributed to that song. Andy played great bass on it. He actually stayed out for the first verse and doesn’t come in until later. I mean, talk about economy! Then he does that sort of bass solo and of course Simon’s drums are fantastic too.

I’m very grateful for it, because it’s known throughout the world, and who would have believed that could happen? We were just teenagers. I was 19 and Andy was 17.

How did you and Paul Kossoff work together in Free, and how did his guitar playing affect your own development on guitar?

When Free first got together, Paul and I would listen to Albert King, B.B. King, Cream and Hendrix, and we could hear the question-and-answer that went on between the musicians and the space required in order to have a conversation musically. And then there’s room for the listener to step inside the music. There’s a certain amount of suggestion that something is about to happen and you have to wait for the moment. I think we listened to the right people.

We were fortunate in that, because John Lee Hooker and Aretha Franklin and those great masters of the genre created emotional music that touches peoples’ hearts. We listened to that and soaked it up, and we tried to emulate that. Some of it was 40 years old, but it was new to us and it sounded so different from everything else we were listening to that was around.

So I think our influences were very similar. Paul loved to do “Born Under a Bad Sign” and he suggested we do “The Hunter,” which became a huge song for Free. Koss was economical in his approach and that rubbed off on me.

The first couple of songs I wrote, like “Walk in My Shadow,” he put some real balls into that riff. Also, there was a song called “Moonshine” [from Tons of Sobs]. He had written the music to that and asked me to write lyrics to it. That was the song that we were playing when the rest of us met Alexis Korner, because he was a friend of Andy Fraser’s.

Alexis walked into the rehearsal room and sat down, and we took a break and he said, “Well, you’re a group now. All you need now is a name.” And we came up with Free.

Paul wasn’t able to go to Japan with Free on its July ’72 tour. As a result, you not only sang but also played all the guitar parts.

I remember speaking to [drummer] Simon Kirke and saying, “Well, we could just go and wing it.” I knew the parts because I’d written it on acoustic, so I had to translate that over to electric and just did that.

Your solos tapped into a vein of expressive emotion. I think strapping on a guitar and being in a band with Kossoff is just going to inspire you.

Absolutely. With the economy of his guitar playing, I think that’s definitely related to the way I sing. That’s how I hear music. But that’s why I don’t sing and play too much. There are people that can really do that, but if I’m going to sing, I want to focus on the vocals.

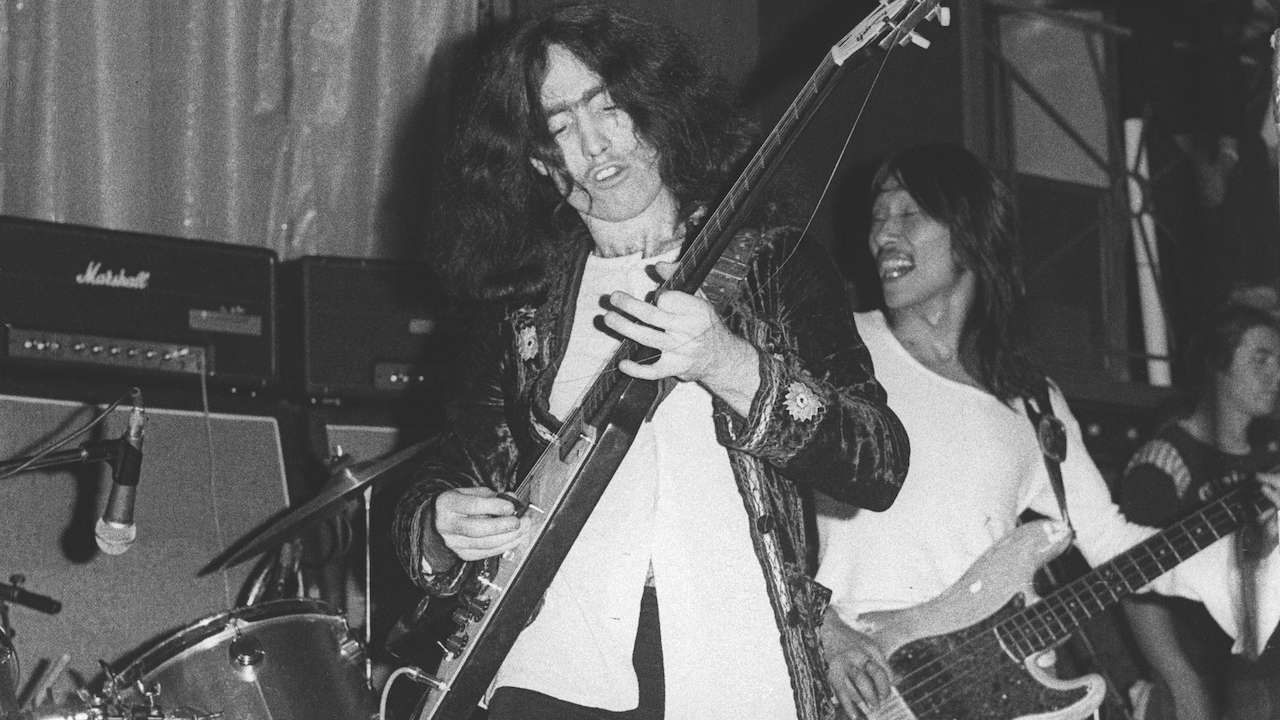

You’ve created some indelible guitar riffs. What inspired the riff in “Rock Steady” [from Bad Company’s self-titled 1974 debut]?

That was actually written on a bass. I had an Echo bass. It was acoustic, but you could plug it in as well, so it was nice to sit around and play because it was loud enough. I wrote “Wishing Well” for Free with that. I learned a lot from Andy Fraser, the bass player in Free, just from listening and being around him. His bass playing was masterful.

“Rock Steady” has a big guitar riff. I played it to Mick [Ralphs], and Mick could take my guitar riff ideas, even if I played them acoustically, and translate them into electric. So Mick came up with a great addendum to the riff by sliding his finger up a couple of strings instead of just playing the bass notes. He did that with all his playing. If you listen to “Silver, Blue and Gold” [from 1976’s Run With the Pack], he plays to the song, and it really enhances it. His sound is unique and his chordal focus is impressive.

So you could imagine “Silver, Blue and Gold,” and then you go to “Burning Sky” and the guitar part is very growly. And then with “Electricland,” his sound becomes magical. It’s like you’re in another world. Mick was always great at that.

Tell me about that huge riff that underscores your acoustic playing in “Feel Like Makin’ Love” [from 1975’s Straight Shooter]. Who came up with that?

I started to write that song when I was with Free and we were touring America. I was in San Francisco and I met up with a whole group of hippies. We got real friendly and hitched north about a hundred miles from Frisco. We were in an area with these big beautiful, almost cathedral-like redwood trees in the forest. It was absolutely beautiful. I started to write that song there and it never got finished. It just stayed somewhere on file in my mind.

Shooting Star” was written about all the casualties in rock and roll. A lot of people ask me if it was written about Paul Kossoff, and yeah, it was, but it’s also about Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Brian Jones

We sat down to write songs for our second album, Straight Shooter, and Mick said to me, “So what have you got?” And I said, “Well, I’ve got this idea and I don’t know quite what to do with it,” and I started singing and playing the verse. And Mick goes, “What it needs is this,” and he came up with that big chorus riff, those big power chords. It didn’t have a chorus, but Mick’s guitar riff inspired me to sing the words “feel like makin’ love,” and that became the song.

On the song “Deal With the Preacher,” from that same album, I came up with the original idea and Mick really enhanced it and took it to another level.

Did you come up with the epic riff for “Shooting Star” [from Straight Shooter]?

Yeah, that was me, actually. Pretty powerful stuff. “Shooting Star” was written about all the casualties in rock and roll. A lot of people ask me if it was written about Paul Kossoff, and yeah, it was, but it’s also about Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Brian Jones and all of those casualties of the business. I didn’t think it would run so deep and be so meaningful in the sense that it applies to so many people, in a more general way.

Let’s touch on a few of your classic guitar solos. One is the harmony solo you played on Bad Company’s breakthrough smash hit, “Can’t Get Enough.” Do you recall laying that down with Mick Ralphs and working out the part?

We recorded the first Bad Company album at Headley Grange [the former workhouse in Headley, Hampshire, where Led Zeppelin frequently wrote and recorded], using Ronnie Lane’s mobile unit. We had done a lot of rehearsing and we were bursting at the seams to put this stuff down.

Our first album had a very rough edge and natural ambiance. We didn’t have a lot of toys to play with, but it was a mobile studio and we were in this huge mansion. The sound had a natural ambiance. If you heard echo it tended to be natural echo, and I think that’s a good thing. Mick came in with the whole solo in “Can’t Get Enough” and he taught me my part.

We did it in the living room at Headley Grange. It was a great big living room with all this furniture in it, a big log fire at the end, and we put the solo on there.

Once we’d got the track down, we overdubbed the solo together. It was great playing it together, because there was a kind of edge to the distortion and it jelled really well, much better than a clean overdub. We also did the vocals for “Rock Steady” there, with all of us doing the backing vocals.

Many readers may not be aware that it’s you playing lead guitar on “Rock and Roll Fantasy” [from 1979’s Desolation Angels].

We were living a rock and roll fantasy at the time. When [Led Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant started to manage us, and Led Zeppelin got behind us and actually introduced us to America — which was great of them — it was really fantastic.

Actually, I played guitar throughout “Rock and Roll Fantasy,” including the solo, and Mick very kindly let me go ahead. He added some unique touches, as only Mick Ralphs can. The solo was just part of the composition. I thought, Well, I’ll just stick it on myself.

I used what was at the time a new cutting-edge Roland synth guitar. It was very exciting. It was the ultimate rock and roll guitar sound that really inspired me. You could play all sorts of sounds on the guitar:

You could have bass, you could have harpsichord... And I thought, Well, wouldn’t it be crazy just to put them all in? And so let’s see how that sounds. I thought, Christ, this is a rock and roll fantasy! And that’s where the idea for the song came from.

As for the guitar solo on that song, I think if anyone influenced me it was George Harrison. George always had solos that were very in tune with whatever track he played on — something that was very suitable and always hit the mark. So I think I might have been influenced a little bit by George.

You’ve been fortunate to work closely with four gifted guitar players through the years. Tell me what makes each special, starting with Paul Kossoff.

He put everything he had into every note. He was tearing his soul out with every note that he played. There’s a song that Free did called “Come Together in the Morning,” and the solo just rips my heart out. It’s just such a beautiful solo. I love Koss’s playing.

How about Mick Ralphs, who, out of all the guitarists you’ve played with, may be the most unheralded player. But he’s incredibly creative.

Well, I think he’s very versatile and his sound is very versatile, and he locks into a song perfectly. If it’s “Can’t Get Enough” or “Bad Company,” or “Feel Like Makin’ Love” or “Shooting Star,” you can immediately recognize his playing and go, “That’s Mick Ralphs.” But it’s different each time, and you hear that they’re different from each other. On “Silver, Blue and Gold,” he’s got just the sweetest sound, and it’s very appropriate to the song.

Jimmy Page is one of the greats. What impressed you most about his playing when you began working together in the Firm”?

He could take a solo and lift the whole band, the audience and the whole auditorium straight into outer space, and everybody was with him. He could do that, and it was just tremendous. We were just along for the ride sometimes. It was so amazing.

You played the very avant-garde solo on “Radioactive.”

I got a few looks from Jimmy on that one. [laughs] I did a demo of the song and went, “This is how I want the solo to go,” and I sort of expected him to play that. He said, “Why don’t you play it?” and so I did. It’s a finger exercise Alexis Korner showed me. It’s really, really difficult, even when I try it now. But I put that on, and then I put it on backwards against itself, and it sounded suitable for a track called “Radioactive.” I think I was using Paul Kossoff’s [1958 ’Burst] Les Paul on that one.

How about Brian May?

Brian May is a superb guitar player. Before we got together for Queen, he played for me on my Muddy Waters album [1993’s Muddy Water Blues: A Tribute to Muddy Waters]. He told me, “I don’t really play the blues,” and I said, “Well, I’m sure you do, Brian. It’s just the same as anything else. You just have to feel it, right?”

So he comes into the studio and he played a guitar solo, and it was great. And he said, “Is that all right?” and I said, “Yes, it’s really fantastic!” And he said, “Well, do you think I could put some harmonies on it?” I said, “Yeah, absolutely.” And he put a harmony on it and I said, “Wow, there’s Queen right there!”

I’ve always felt that Paul Rodgers is not a rock and roll singer — he’s a soul singer who sings rock and roll.

That’s lovely. I like that, and I think it’s very true. I identify with the soul singers very much and their pain and the blues and soul.

I know you love Wilson Pickett. I recently heard his cover of Free’s “Fire and Water.” Being such a staunch fan of soul singers, you must have had your mind blown when he covered it.

It was unbelievable. I certainly didn’t solicit him to do the song; they just chose to do it. And it was such a feather in my cap, because he’s one of the people I was aiming at. He set the bar with “In the Midnight Hour” and all that kind of stuff.

Even now, when I listen to “In the Midnight Hour,” it is amazing the band has got all the time in the world, and it’s moving along and he just nails it.

I met Wilson near the end of his life, and you know what he said to me? “Write me some more songs.”

‘The guitar was his healing instrument’: Cynthia Kereluk, Paul Rodgers’ wife and collaborator on his new record, opens up about his strokes and his long road back to health

Paul Rodgers can certainly keep a secret. Little did anyone know until this past autumn that he spent much of the previous seven years dealing with serious health issues that nearly killed him. As his wife Cynthia Kereluk Rodgers tells Guitar Player, his problems began in 2016 with a near-fatal heart attack.

“We caught his would-be widow-maker heart attack before it actually happened,” she recalls. “He had a stent put in. We got to the hospital with 10 minutes to spare, and we’re lucky we got there.”

The scare was followed by a period in which Rodgers had 11 TIAs — transient ischemic attacks — “which were really sneaky,” Cynthia explains. “We didn’t know that they were TIAs. He’d just have a bad headache, or he felt like the band was out of tune behind him.”

Rodgers then suffered two strokes: one in 2016 and another in 2019. The second left him non-verbal and physically impaired. “He couldn’t read, couldn’t write, had to learn to walk, had to learn to talk, had to learn everything, how to eat,” she says. “All the basics were gone, including how to sing and play.”

His doctors determined that Rodgers needed an endarterectomy to remove plaque from his his left carotid artery. “They told him that he may or may not come out of it,” Cynthia says. “But his left artery was 95 percent blocked. So it was surgery or death. We had no choice in that matter.”

Rodgers emerged from surgery just fine, but recovering his ability to play guitar and sing took about a year and a half.

“I knew that music would bring him back,” Cynthia says. To encourage him, she left his guitar out for him on the sofa, in its case, with the lid up. He walked by it for a few months, but eventually he began to pick it up.

“I saw him on the couch sitting with the guitar on his lap after probably eight or nine months, and he was strumming the guitar away from his body with both hands, like a slide guitar,” she says. “And then he started playing and got his dexterity back in his hands. And then after quite a few months, the voice came back as well. The guitar was his healing instrument.” — KS

Paul Rodgers’ latest album Midnight Rose is available to stream and buy now