All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

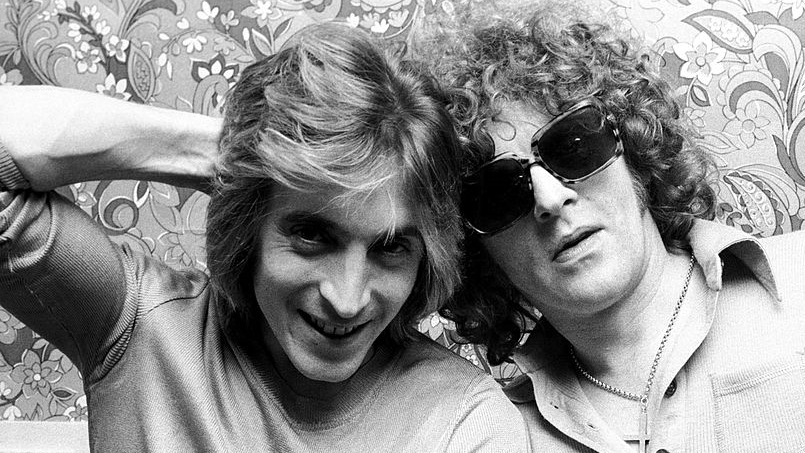

In 1970, Mick Ronson changed the musical fortunes of David Bowie, a struggling singer-songwriter with two novelty hits behind him.

Together, and with their band the Spiders From Mars, they reinvented Bowie musically and created some of glam-rock’s best-loved albums: Hunky Dory, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, Aladdin Sane and Pin Ups.

Afterward, Ronson struggled to match that initial success, despite a catalog of collaborations that included some of rock’s biggest names: Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, Ian Hunter, Roger McGuinn, Morrissey, John Mellencamp and many others.

Although Ronson’s career was defined by his time with Bowie, there was a significant before and after

Although Ronson’s career was defined by his time with Bowie, there was a significant before and after.

In the 1960s, he played in various groups from his hometown of Hull, including the Mariners, who were advised by the Rolling Stones’ Bill Wyman to change their name to the King Bees around the time Bowie was fronting a group called Davie Jones and the King Bees.

He was also a member of the Rats, whose main claim to fame was the 1967 single “The Rise and Fall of Bernie Gripplestone.”

“Mick was the best guitarist in Hull, so when he left to head down south and join Bowie, I was pretty upset,” recalls Benny Marshall, the Rats’ lead singer and a close friend of Ronson’s.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mick was the best guitarist in Hull, so when he left to head down south and join Bowie, I was pretty upset

Benny Marshall

“John Cambridge, our drummer, had played with Bowie on Space Oddity [his second album, a.k.a. David Bowie]. He was the bloke who went back to Hull in January 1970 with the brief to find Ronson and bring him to London. He found Mick marking out the lines on the municipal football pitch.”

Cambridge did as instructed, and Bowie and Ronson were introduced at the Marquee club, where Bowie was playing on February 3, 1970.

Two days later, Ronson had learned the riffs and song arrangements well enough to back Bowie, Cambridge and bassist/producer Tony Visconti for a John Peel Radio 1 show live in concert at the Paris Theatre in London’s Lower Regent Street.

They played 15 songs, including a new number, “Width of a Circle,” and plenty of material from Bowie’s recently released self-titled second album.

Reaction was positive, and Ronson moved into Bowie’s Haddon Hall apartment on Southend Road in Beckenham, becoming part of the family. The timing of his arrival was perfect: Bowie wanted to make a hard-rock album.

We needed someone to be [that] important element, and that somebody was Mick Ronson

Tony Visconti

As Visconti said later, “We respected groups like Cream, but we didn’t have that in us. We needed someone to be [that] important element, and that somebody was Mick Ronson.”

In terms of his personality, Ronson was a good fit. Everyone loved Ronson’s laconic Northern humor too, especially Bowie, whose father and mother came from Yorkshire and Lancashire, respectively. He’d tease Ronson and get just as good back.

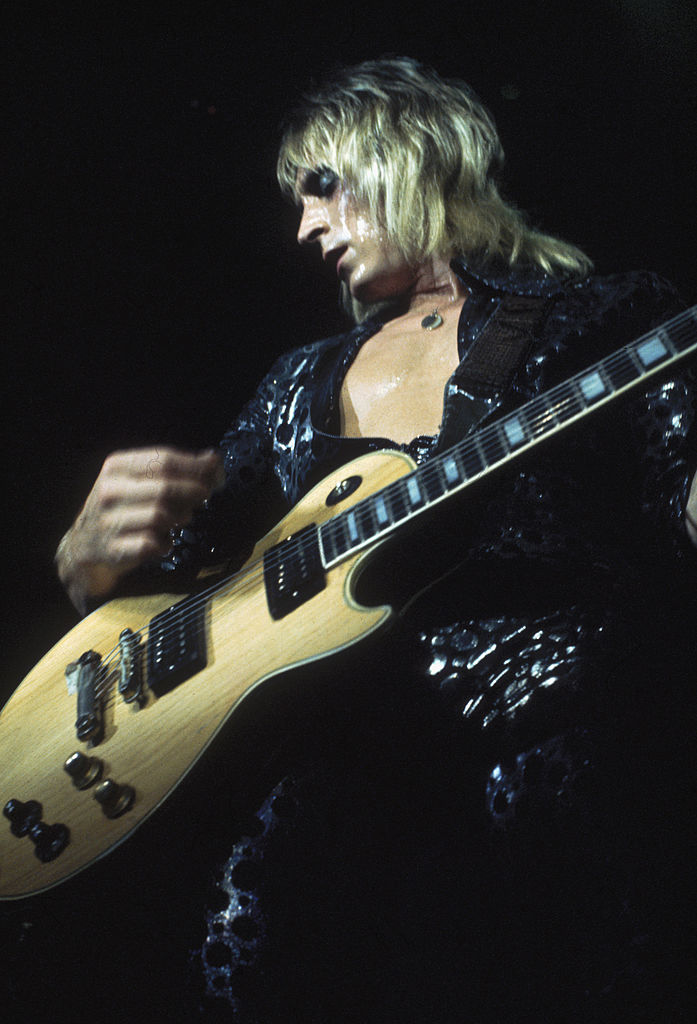

But it was, of course, his guitar playing that stunned them.

“He floored us,” Visconti said. “When David and I met him, we knew he’d fit in looks-wise, but we had no idea what was coming until he picked up his Les Paul and played for us.

“He really didn’t have to be taught the few songs we’d already worked up with John Cambridge. Mick watched our hands on the guitar and bass necks, and he just knew what to play, but he didn’t say much.

“We thought he was just a cool, silent type. Later we found out that our apartment in Beckenham was very ‘big time’ for him, and he was simply overwhelmed.”

We knew he’d fit in looks-wise, but we had no idea what was coming until he picked up his Les Paul

Tony Visconti

Visconti insists Ronson came to Trident Studio in September 1969, when the David Bowie/Space Oddity album was being finalized.

“Mick came to the mix of ‘Wild-Eyed Boy From Freecloud’ and was persuaded to play a little guitar line in the middle part and joined in the handclaps on the same section,” he says.

But if he did, he isn’t credited.

Ronno’s first recorded work with Bowie was on the remade and rocked-out single “Memory of a Free Festival Part 1/Part 2,” recorded in September 1969 and released to zero chart success in June 1970.

In April, sessions began for The Man Who Sold the World, featuring the core band of Bowie, Ronson, Visconti and former Rats drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey.

It was a brilliant album, full of Ronson’s crunching heavy-metal attack allied to arcane Wagnerian, dystopian lyrics.

His contributions to Bowie tracks such as “She Shook Me Cold,” “Running Gun Blues” and the epic “Width of a Circle” cemented his place in Bowie’s orbit, leading the singer to call him, with a smug smile, “my Jeff Beck.”

As it happened, both Bowie and Ronson were huge fans of Beck’s Truth album. Marshall says, “[Mick] knew all the licks, except ‘Beck’s Boogie,’ which he dissected but couldn’t master. It infuriated him.

“In 1968, the Rats had supported Beck at the Cat Ballou in Grantham, and afterward Ronno asked him to show him the fast run at the beginning. So Beck plays it, and Mick says, ‘No, play it slower.’ Beck said, ‘If I play it any slower, I’ll stop!’ But he was patient, and Mick learned that riff.”

The Man Who Sold the World had not been a commercial breakthrough, but it added to Ronson’s confidence.

Visconti and Ronson had masterminded the sound and dashed off the arrangements, while Bowie canoodled with his new bride, Angie.

“She Shook Me Cold,” the dirtiest song he ever wrote, was directly about Mrs. Bowie, but it was Ronson who provided the Jimi Hendrix-style intro and the power-trio setting à la Cream.

Later, Angie lamented the fact that Ronson didn’t receive the publishing he deserved.

“In terms of kudos and feeling that one is valued, it would have been nice for Mick Ronson to have had publishing credits,” she said.

In terms of kudos and feeling that one is valued, it would have been nice for Mick Ronson to have had publishing credits

Angie Bowie

Visconti’s departure from the group saw the arrival of bassist Trevor Bolder. It also gave Ronson his in.

“[Visconti had] done all the string and piano arrangements, so it was my chance to fill the gap,” Ronson said.

“I’d never done it before, but I could read and write music, and I’d watched Tony at Haddon Hall, writing in the basement, saw how he did the charts, and I’d help out.”

Ronson had already written a mini-score for four recorders, used in the break of “All the Madmen.” It was a start.

“I thought, Well, if you can do that then so can I,” he said. “I went out for dinner with [singer] Dana Gillespie, who had tracks that needed strings, and David said, ‘Oh, Mick’ll do that!’ [Like Bowie and Ronson, Gillespie was managed by Tony Defries’ MainMan company.]

“I never had, but it was great. David pushed me forward. That was his thing. He made stuff happen.”

David pushed me forward. That was his thing. He made stuff happen

Mick Ronson

With Visconti gone, Bowie was now heavily reliant on Ronson. His next album, 1971’s Hunky Dory, saw the emergence of his new quartet, featuring Ronson, Bolder and Woodmansey, a taut group that gave his folkie tunes their strong rock underpinnings.

Ronson finally got his credit as the arranger of its songs “Changes,” “Life on Mars?,” “Kooks,” “Quicksand” and the Biff Rose cover “Fill Your Heart,” which was copied virtually note for note from the original.

In retrospect, many have noticed how similar the sound of Hunky Dory is to Michael Chapman’s Fully Qualified Survivor, the 1970 album on which Ronson had made his debut.

Ronson’s burgeoning role extended to instructing hired gun Rick Wakeman for his now iconic piano parts on “Life on Mars?” The Royal College of Music-trained keyboardist (and future Yes member) didn’t mind the input.

“He was a tremendous human being, with oodles of talent,” Wakeman said.

He was a tremendous human being, with oodles of talent

Rick Wakeman

Bowie producer/engineer Ken Scott points to “the great orchestral versions that Ronno put together. [They’re] even more brilliant when you consider he had this habit of running out of time.

“I remember him rushing in 10 minutes before the session, running up to the bathroom and locking himself in so he could find the privacy to finish writing. He’d come out with a huge grin and a stack of charts.”

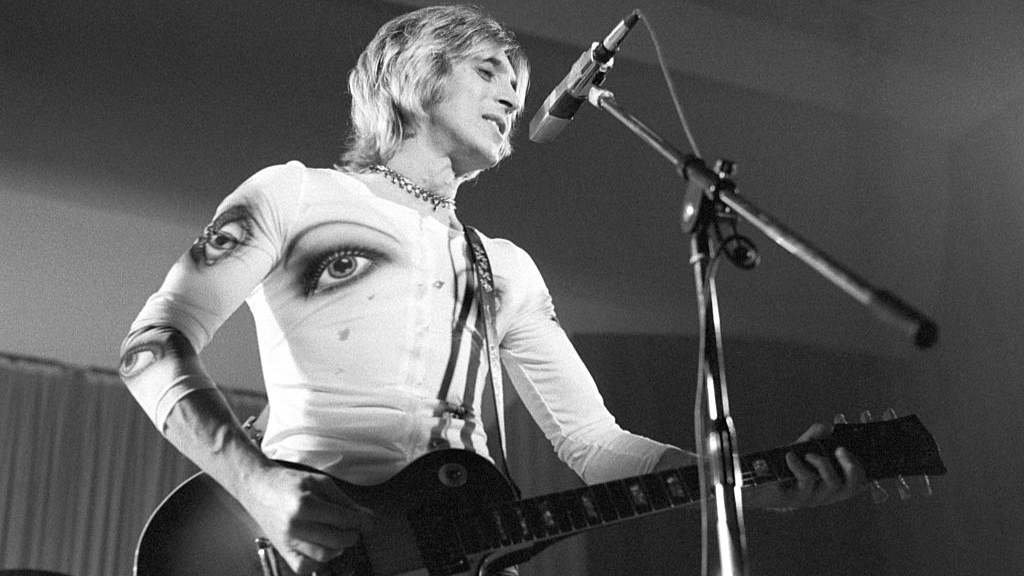

By the time the band assembled for the followup, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, Ronson’s talents were in full bloom.

On the epic “Five Years,” his string section whipped up the hysteria, while on “Suffragette City,” it was Ronno who came up with the funky, lurching ARP synthesizer sound that many mistake for saxophones.

But working with Bowie had its challenges for Ronson, a now 25-year-old who, until recently, had been a practicing Mormon.

In January 1972, shortly before the Ziggy Stardust sessions were complete, Bowie told Melody Maker he was gay, or, more accurately, bisexual.

Ronson admitted he found it hard to deal with at first. “It embarrassed me,” he said. “I wondered what people would say about me. I knew my family in Hull would get flak. I gave dad a car when I left for London, and people threw red paint over it.”

I knew my family in Hull would get flak. I gave dad a car when I left for London, and people threw red paint over it

Mick Ronson

Aside from his own feelings about it, Ronson understood Bowie was playing with his image as a way to keep the media engaged. “Personally, it was a bit of a shock,” he admitted, “but Bowie manipulated the media again and again.”

Overall, Ronson approached the Ziggy Stardust project with slight suspicion. The explicitness of “Suffragette City” and the discarded track “Sweet Head” concerned him.

“He worried about the lyrics,” Angie says. “I told him. ‘Look, all these people are waving their arms in freedom thanks to you. It may not be what you’re used to in Hull, but accept it.’ Then he’d simmer down and be happy.”

If Ziggy Stardust was a Ronson tour de force, the follow-up, Aladdin Sane, was a mixed blessing for him.

His contributions were immense, but so were those of recently arrived pianist Mike Garson, whom Ronson had auditioned and later advised to “make yourself indispensable. That’s what David likes. Don’t just be a session man.”

Certainly, Ronson lived up that credo. His work on Lou Reed’s Transformer, produced with Bowie the August after Ziggy Stardust, effectively rescued Reed’s career after his debut solo album had bombed.

'Transformer' is easily my best-produced album. That has a lot to do with Mick Ronson

Lou Reed

“It was a good experience for me,” Ronno said. “Lou’s guitar was always out of tune, so I’d kneel in front of him and tune it properly. He didn’t care, ’cause he was so laid-back.”

Without his contribution, Transformer might never have got off the ground.

“It came out pretty well,” Ronson said. “Though I didn’t know what the hell [Lou] was talking about half the time. He’d say stuff like: ‘Can you make it sound a bit more grey?’”

Fortunately the album was a roaring success.

“Transformer is easily my best-produced album,” Reed said. “That has a lot to do with Mick Ronson. His influence was stronger than David’s, but together, as a team, they’re terrific.”

By 1973, though, it seemed that Ronson had become dispensable, along with Woody Woodmansey and Trevor Bolder, both of whom had been dropped for having the gall to protest when they discovered that new arrival Garson was making 10 times their salary.

The guitarist’s relations with Bowie were frosty when, on October 20,1973, Ronson played with Bowie onstage for the last time in that decade.

Only 200 people saw the appearance in the flesh, shot for NBC’s The Midnight Special. Dubbed “The 1980 Floor Show,” the concert featured Bowie serenading French singer/actress/model Amanda Lear with “Sorrow,” a 1966 hit for the Merseys that Bowie would record for 1973’s Pin Ups, an album on which he covered songs from the Swinging London era.

He and singer Marianne Faithfull also duetted on Sonny & Cher’s “I Got You Babe.” But Bowie hated the end result, which he derided as “shot abysmally.”

This was the night Ziggy Stardust truly left the building, which may explain why a smiling Bowie ended each song with an affectionate pat on Ronson’s white satin-clad back.

As the wingman was increasingly sidelined, MainMan, his and Bowie’s mutual management company, promised him the earth.

He was to be the next superstar off the production line, said manager Tony Defries. In the summer of ’73, having finished his sessions for Pin Ups, most of which he’d arranged, as usual, Ronson returned to the Château d’Hérouville studios outside Paris and made his solo debut album, Slaughter on 10th Avenue.

Bowie chipped in from a distance, gifting the songs “Growing Up and I’m Fine,” “Pleasure Man/Hey Ma, Get Papa” and “Music Is Lethal.”

RCA weren’t overjoyed with what it heard, and the album’s release date was put back more than six months, to 1974.

Within months, Ronson was back in another band, joining Mott the Hoople for what would be their final single, “Saturday Gigs.”

Ronson and frontman Ian Hunter had bonded back when Mick had knocked out a string arrangement for Mott’s “Sea Diver,” but the other band members resented the arrival of this “rock star” in their midst, with MainMan and RCA sending limos for their boy while Mott traveled together in a bus.

Tired of the conflict, Hunter split the band.

Ronson went back to his solo career. Bowie didn’t take part in the follow-up album, Play Don’t Worry, but he allowed Ronson to use the backing track from their cover of the Velvet Underground’s “White Light/White Heat,” which had been recorded for an American attempt at a Pin Ups album that was discarded soon after.

Play Don’t Worry was excellent in parts. Although he wasn’t a natural songwriter, Ronson did himself proud on the opening “Billy Porter,” “Empty Bed” and versions of two songs by Pure Prairie League, whose 1972 album Bustin’ Out featured his guitar and string arrangements.

While Slaughter on 10th Avenue was being mixed, Ronson returned to the studio with Bowie to create demos for the future Diamond Dogs tracks “1984” and “Dodo.”

When Mick heard ‘Diamond Dogs,’ he wasn’t exactly depressed. He just thought, Oh, that’s Dave going out on a limb

Suzi Ronson

His work wouldn’t appear on the finished album, a creepy, avant-garde affair, but his trademark guitar style did in the shape of “Rebel Rebel,” almost a Spiders From Mars pastiche riff, played now by Bowie.

According to Ronson’s wife, Suzi, “When Mick heard Diamond Dogs, he wasn’t exactly depressed. He just thought, Oh, that’s Dave going out on a limb. But he would have done that record like a shot.”

Instead Ronson embarked on a mercifully brief solo tour, including a show at London’s Rainbow Theatre in February 1974, where he had strings and woodwind sections and, on backing vocals, the Thunderthighs – Karen Friedman, Dari Lalou and Casey Synge – who famously appeared on Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” and Mott the Hoople’s “Roll Away the Stone.”

Cast into the spotlight, Ronson didn’t appear overly confident. The ultimate sideman was too modest to carry this off.

Bowie watched on from the wings and offered words of encouragement during the intermission, but decided against making a guest appearance.

After Bowie, where does one go? Ronson produced and played on Ian Hunter’s self-titled 1975 debut solo album.

That same year, he moved to New York City, rented a place on Hudson Street near the Meatpacking District and enjoyed the city with his best friend Hunter, who had provided safe haven via Mott the Hoople, Mott, and the Hunter Ronson Band.

This is where they met Bob Dylan, who invited Ronson to join his band of gypsies, the Rolling Thunder Revue, after a meet engineered by Dylan’s main fixer, Bob Neuwirth.

That evening began at the Bitter End, on Bleecker Street. “We weren’t Dylan fans at all,” Suzi Ronson says. “Mick thought he sounded like Yogi Bear. But Ian took us anyway, and Dylan played [his 1976] Desire album, and he was mezmerising, better than David.

“Then we went to the Bottom Line, where Mick got thrown out three times for being drunk and disorderly.”

Dylan phoned me, said the tour was going to happen and would I be there? Like a shot!

Mick Ronson

Back at the Bitter End, Hunter recalls “the whole place going insane ’cause Dylan was singing with Neuwirth and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. And Neuwirth [sees] Mick and says to Dylan, ‘Go and ask him!’”

In Ronson’s version, “[Neuwirth] was with this guy,” he recalled. “And I looked at this bloke he was with and thought, Wait a minute, I know you! And, of course, it was Dylan. And we talked, and he said, ‘We’re going on the road. Why don’t you come with us?’

“I honestly thought it was a hoax. Then Dylan phoned me, said the tour was going to happen and would I be there? Like a shot!”

“That tour rescued Mick’s professional life,” Suzi says.

Ronson was soon back with Hunter, appearing on You’re Never Alone With a Schizophrenic and Welcome to the Club.

With his solo career on hold, he became a full-time producer. He worked with Van Morrison, John Mellencamp, Roger McGuinn and Meat Loaf backup singer Ellen Foley. He even contributed guitar to the title track from David Cassidy’s 1976 album, Getting It in the Street.

Despite his signature guitar style and tone, Ronson became engrossed in writing string arrangements.

“He lapsed into the language of strings,” Hunter says, “but he was a bit lazy, ’cause if it was interesting he’d do it using 15 tracks and one guitar track.

“He wrote arrangements on Marlboro Light fag packets. But he could be persnickety and picky if he was involved. He could have matured into a world-famous musician again, but he’d meet people on the street and, next thing, he’s doing a Mexican punk band.”

He was great with fans. He’d invite them back for tea, he’d return their phone calls

Ian Hunter

“But he was great with fans. He’d invite them back for tea, he’d return their phone calls. Sometimes he could be the big guy and show off, so he wasn’t perfect, gorgeous as he was. I considered him like family, so there were arguments.

“One time he disappeared to Sweden for a project when we were in the middle of something, so I had a go. And he just said, ‘Look, I’ve done Bowie and I’ve done you, so I’m allowed to fuck up,’ and we just collapsed into laughter.”

In the late 1980s, Ronson’s health began to cause concern. He was diagnosed with liver cancer, something he neither made a secret of nor chose to acknowledge as a threat. Instead he threw himself into projects such as Morrissey’s 1992 album, Your Arsenal.

Speaking with Classic Rock, Morrissey said, “Mick told me that he alone wrote the main guitar hooks for ‘Starman,’ ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ and others – not just hooks, really, but grand choruses in themselves – but a share of publishing wasn’t ever on offer for him.

“When you consider his solos in ‘Time’ and ‘Moonage Daydream,’ then you can guess that they were his own creations.”

A fan of both Ronson and Bowie, Morrissey was intrigued by letters Bowie sent to his old guitarist chum during the making of Your Arsenal.

“One day at breakfast, I asked Mick why Bowie wrote so often,” Morrissey recalled, “and he said, ‘He keeps asking me what you’re like in the studio,’ and then he exploded with laughter.

“I have no idea why this was so hilarious. I think Bowie had interest in Mick only as much as it was in his nature to like anyone.”

I think Bowie had interest in Mick only as much as it was in his nature to like anyone

Morrissey

Certainly, Bowie was impressed by Your Arsenal enough that he invited Ronson to work with him on his 1993 studio album, Black Tie White Noise.

He also kicked off a fine version of “All the Young Dudes” with Bowie and Hunter at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert at Wembley Stadium on Easter Monday, 1992, which was the last time his fans saw him onstage.

One year later, on April 29, 1993, Ronson died of liver cancer at age 46.

He spent his last hours in the company of Hunter, Suzi and sister Maggi at Tony Defries’ house on Hasker Street in West London.

Ronson didn’t die penniless, but he wasn’t wealthy by rock star standards.

“He bought the house in Woodstock on Glasco Turnpike [in New York State] because he made money out of my records and Ellen Foley’s Night Out,” Ian Hunter says. “His car was an old Toyota Corolla that sounded like a hair dryer.”

Hunter summed up the gloomy finale in his Ronno elegy “Michael Picasso,” from 1977’s The Artful Dodger: “You turned into a ghost surrounded by your pain/And the thing that I liked the least was sitting round Hasker Street, lying about the future.”

As a rock duo, I thought we were as good as Mick and Keith

David Bowie

“As a rock duo, I thought we were as good as Mick and Keith.”

“What is remarkable is that he was so overlooked, and he still is,” Morrissey said of Ronson. “Has Mick ever been on the cover of a major British music magazine? Even when he died? He was by nature extremely humble. He was just happy to be there.”

Though he was the first of many great guitarists Bowie would adopt, champion and cast aside, Ronson continued to hold a place in his heart after their split, perhaps more than any other who followed him.

“Mick was the perfect foil for the Ziggy character,” Bowie admitted years afterward.

“He was very much a salt-of-the-earth type, the blunt northerner with a defiantly masculine personality, so what you got was the old-fashioned yin-and-yang thing.