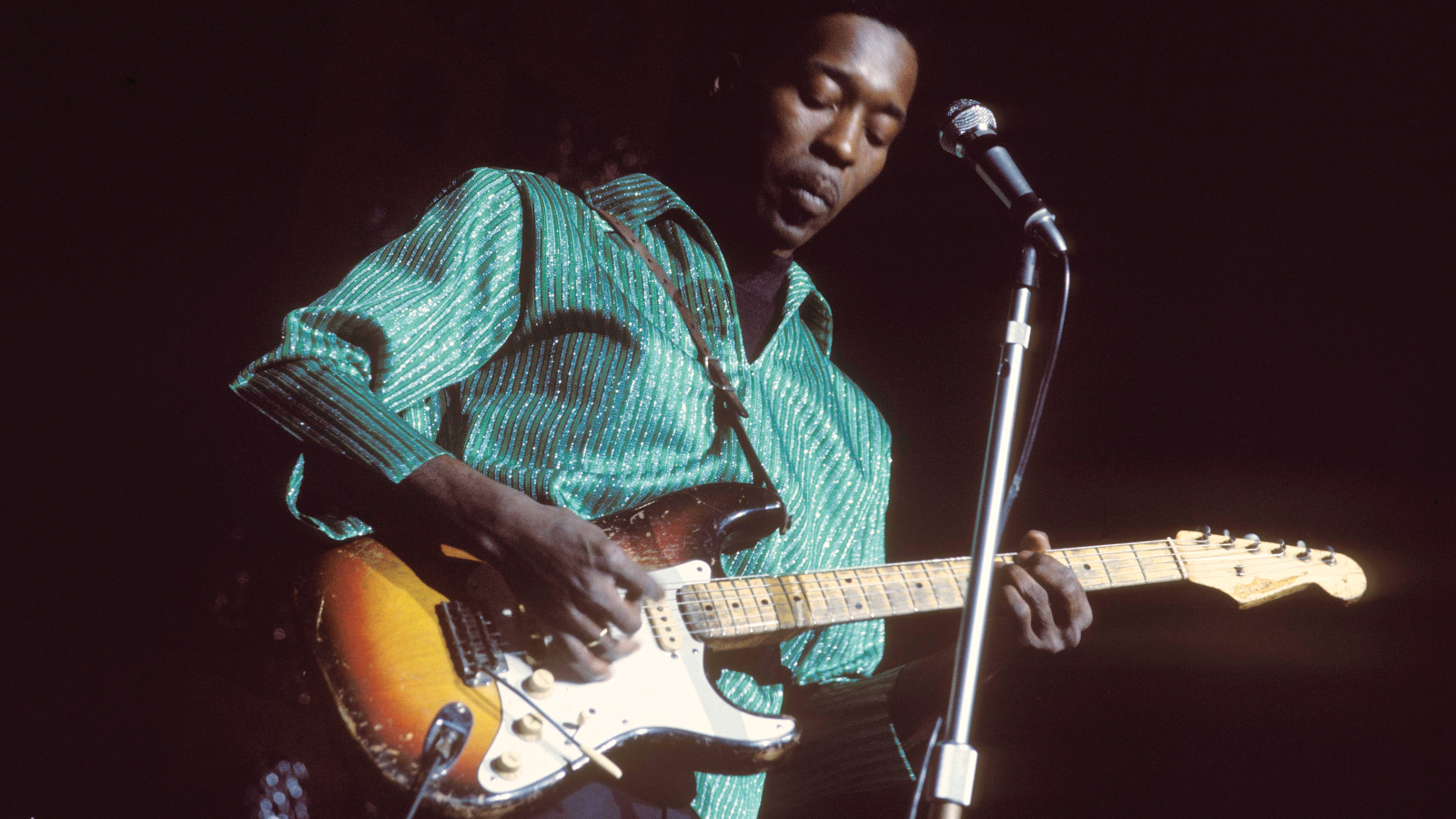

“He Said, ‘I Just Canceled a Gig, ’Cause I Wanted to See You’”: Buddy Guy Talks Befriending Jimi Hendrix

How the blues icon met Jimi (and was invited to kick Leonard Chess’s butt!)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“They talk about Chicago blues,” Buddy Guy says. “But I’m from Louisiana. There were guitarists in Chicago who came from Texas, Alabama, Louisiana… Wolf was from Mississippi, John Lee Hooker and all of them were from down there, man. But Chicago recorded it, and that’s why they decided to call it Chicago blues.

“But I don’t give credit to Chicago for that. I give Mississippi and Texas, Louisiana and Alabama and all those places like that the credit, ’cause those guys knew how to play that way before they came to Chicago. But Chess Records exploded it, so they called it ‘Chicago.’”

Guy was with Chess Records from 1959 to 1968, yet he released just one album of his own with the label: 1967’s Left My Blues in San Francisco, which featured four of his own songs and covers of tunes by Willie Dixon, Sonny Boy Williamson and others.

The production and arrangements were smoother than the grit of his stage performances, or what he played on sessions for Williamson, Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Koko Taylor, Junior Wells and others.

Those contributions were noticed across the Atlantic by the likes of Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and a great many more artists who appreciated American blues more than its homeland did.

“Eric, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and all of them were listening to those licks,” Guy remembers. “I wasn’t thinking about Buddy Guy; I just wanted to do something to please the audience. Every time I did one of them shows, I’d get $20, which was a lot for me back then. But those British guys heard me and they wanted to know who I was.”

Guy told Chess Records co-founder Leonard Chess about Britain’s emerging electric blues scene, but he paid him no mind. Eventually, though, Chess learned that Jimi Hendrix was asking about Guy.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When Leonard found that out, he sent Willie Dixon to my house,” he recalls. “And Willie Dixon said, ‘Put a suit on. Leonard wants to see you.’ When I got down there, Leonard bent over and said, ‘I want you to kick me in my butt.’ I said, ‘For what?’ And he started talking about Eric with Cream, and Jimi Hendrix.

Somebody said to me, ‘Look out, man, that’s Jimi Hendrix over there!’

Buddy Guy

“He said, ‘You came here and told us about them, and we were too dumb to listen. So I want you to kick me in the butt.’”

Ironically, Guy had himself spent little time listening to the very players he’d mentioned to Chess. “So right after he told me to kick him in the butt, I started listening to them myself,” he says.

He soon began meeting them, too.

Around that same time, Guy recalls, “I got invited to play in New York City. I was putting on the ‘Buddy Guy show,’ with my guitar behind my back and throwing it around. And somebody said to me, ‘Look out, man, that’s Jimi Hendrix over there!’ – ’cause those were Jimi’s moves. But I said, ‘So what? Who the hell is that?’

“Eventually, Jimi came over to me and introduced himself. He said, ‘I just canceled a gig, ’cause I wanted to see you.’ And that’s how we became friends.”

Hill Country

Although Guy learned from the blues masters of the South, his recordings were done primarily in Chicago’s contemporary studios. So he was something of a proverbial fish out of water when producer Dennis Herring decided to record Guy’s 2001 album, Sweet Tea, in Oxford, Mississippi, in the raw Hill Country style of R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough.

Guy wasn’t completely onboard at first. “I said, ‘What the hell is this?’ I liked it, but I said, ‘Why have me mess with it? That stuff there is like the national anthem, as far as I’m concerned.’

“But we started doing it, and I started smiling, patting my feet, jumping up and down. I went back to Mississippi and started digging in again. I guess it shows you’re never too old to learn.”

Sweet Tea wound up hitting number one on Billboard’s Blues Albums charts and was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Blues Album.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.