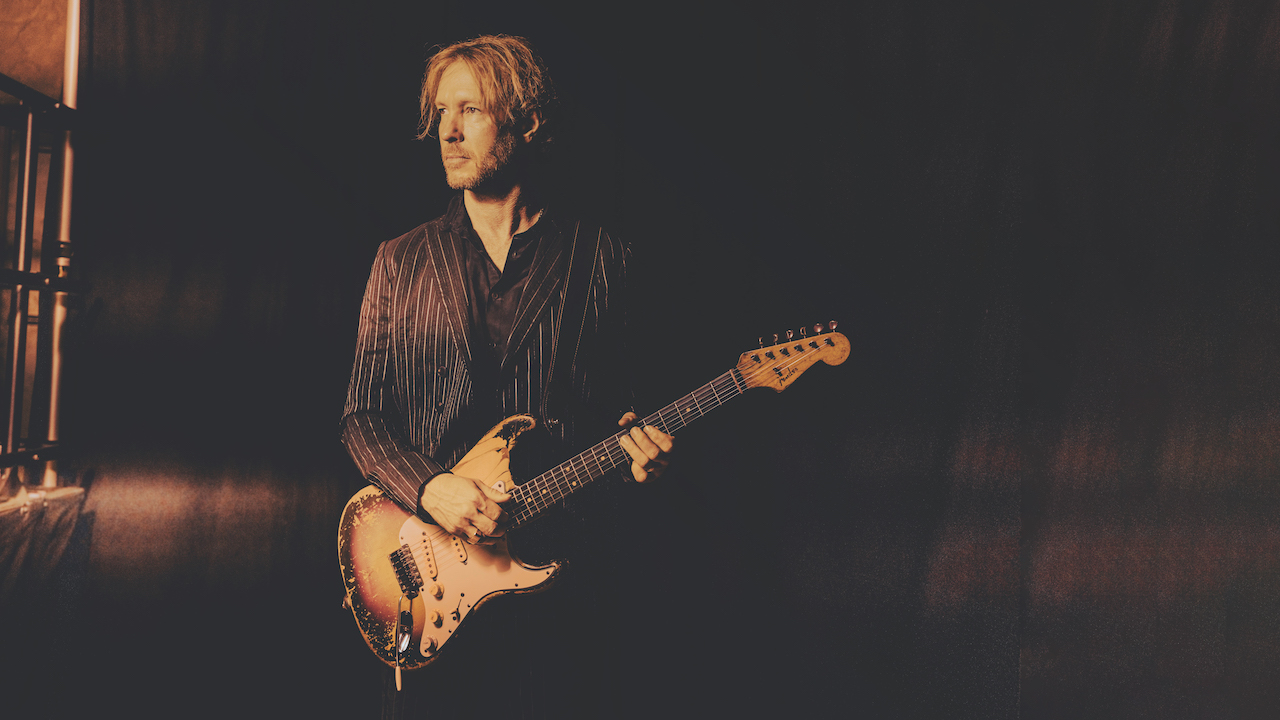

”There’s 12 notes on a guitar and Steve Vai and Zakk Wylde sound like they have more. How do you do that?” Blues prodigy Kenny Wayne Shepherd on his new solo album Dirt on My Diamonds, Vol. 1, and why unpredictability is so important

Looking for fresh inspiration, Kenny Wayne Shepherd left Nashville for Alabama’s FAME Studios. The result is the first half of a new album project that continues his breathtaking blues-rock evolution

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Home is certainly where Kenny Wayne Shepherd’s heart is — and where his body is at the moment, which, given his heavy touring schedule, is not always the case.

But today we find the guitarist and bandleader in the confines of his abode, south of Nashville, where, with six children, Shepherd says it’s even more “nonstop” than any given day in his prodigious touring schedule.

“There’s lots of school, dropping kids off, trying to keep up with where everybody needs to be, what they’re doing,” Shepherd says with a chuckle. “And we’ve been renovating this place since we bought it a few years ago, so I’m helping out with that kind of stuff.”

Domesticity does not delay the music, however. Shepherd — a one-time teen prodigy from Louisiana who’s now 46, with 10 studio albums behind him (plus two with the Rides, his all-star band with Stephen Stills and Barry Goldberg) — spent much of the past year and a half celebrating the 25th anniversary of Trouble Is..., his Platinum-certified sophomore album that topped Billboard’s Blues Albums chart and spawned a number one Mainstream Rock hit in “Blue on Black.”

He even re-recorded the set as Trouble Is... 25, chronicling the growth and depth he’s attained as a player and singer during the past quarter-century.

Waiting in the wings, meanwhile, has been Dirt on My Diamonds Vol. 1, perhaps the most ambitious outing of Shepherd’s career to date. It began with writing sessions he conducted with producer Marshall Altman and others at historic FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where a who’s-who of blues, soul, rock and roots artists left their musical DNA in the walls and carpets.

The Shepherd gang came up with a batch of songs there, from which eight were assigned to volume one. And, yes, there will be a volume two to follow.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It’s an album that culminates what Shepherd has done before and takes the proverbial step forward — sometimes boldly. The blues is still alive and well in his soul — check out “Ease My Mind” — but the ears can’t help but perk up when they hear the subtle scratching underneath the halting groove of “Sweet & Low,” as if Tupac met B.B. King in — where else? — California.

The socially conscious “Best of Times” has a funky, brassy grit, while “You Can’t Love Me” mixes some light country touches into the mix. Shepherd and company also deliver a convincing cover of Elton John’s “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting,” which he even sings with a great deal more clarity than John delivered in the original.

Shepherd clearly had his eye on some new musical horizons here, and his excitement about that intent is contagious as he rapid-fires through the narrative surrounding it. Or maybe he’s just trying to get through traffic in time to pick up the next kid...

You’ve spent some time celebrating the 25th anniversary of your second album, Trouble Is…, during the past couple of years. Did that factor into Dirt on My Diamonds at all?

I don’t think so. They’re pretty separate. I already had the road map there with Trouble Is…. The whole frame of the thing was already established on the original record. Then it became a really special, reflective kind of nostalgic experience, going back and revisiting all that music and re-recording it.

The general feeling, walking away from that experience, is just how well that music has held up over the past 25 years. I still believe that the music and those songs would be as exciting and relevant if they were released today as all-new material.

That’s a hell of a gauntlet to throw in front of a brand-new album then.

Y’know, the new music, it all has ties to the past, right? There is a common thread in all my music, besides it being me. It is the influences; it is the approach. And there’s also been an evolution over the years.

My goal has always been to make albums that sound unique and stand on their own and are unpredictable. I don’t want anybody to think they know what the next album will sound like. I think you can hear that on the new record, pushing in a number of new directions. You can hear a lot of new influences coming into play on the songs and the production of the record.

What do you consider that common thread to be?

It’s like this: Am I a blues artist that plays rock, or a rock artist that plays blues? It’s hard to say. There’s so many different labels — blues guitar player, blues-rock guitar player, contemporary blues… To me this sounds like a fresh, new, young, energetic album. That’s my goal, to continue trying to put the music forward. That’s what I’ve done from day one. “Deja Voodoo” from [1994’s] Ledbetter Heights — that’s not a blues song; it’s a blues-based rock song.

Has your approach to them changed much over the years?

It’s on a song-by-song basis, really, but nine times out of 10 all these songs start with a musical idea that I’ve come up with — a groove or a signature riff, something like that. So it’s built around the guitar as an instrument, which in itself gives the character to the song.

And the grooves just naturally come out of me when I’m trying to create something or write something. I kind of intuitively know where I sit best and which tempos and which grooves I feel are a good platform for me to showcase what I do.

Then, as the song comes together, you’ve got to take into account what is it about? What’s the message here? That influences the approach of the inevitable guitar solo. You have the one in the middle, the one in the ending, and all of the components of the song are going to influence what’s coming out of the guitar when it’s time to solo.

Really, I just try to focus on my strengths. I feel like what I excel at is trying to put riffs and emotions into every note, to try and evoke feelings in people through what I’m playing. I went back and listened to my heroes. When their playing stirred up something in my heart and mind, I’d stop the music and ask myself, What just happened?

And I noticed that every single time I did, it was because the guy played a choice few notes, or even one note, or just, like, this lick, and milked it for all it was worth. It was never this massive amount of notes all played in a hurry for a “wow” moment.

That’s how I wanted to affect people when I play the instrument, wrenching every bit of feeling that I can get out of the instrument through maybe not the most extensive vocabulary of guitar licks but just a few notes — or one note — and strive to take it someplace and do something different on each record. I think that’s served me well.

Who were some of those guitar heroes you referenced?

It’s not as extensive as you might think. Look at a guy like Satriani. Look at Steve Vai, Zakk Wylde, even Bonamassa. It’s baffling to me: There’s 12 notes on a guitar and these guys sound like they have more than 12 notes available to them. How do you do that? But they honed in on those things. Hendrix, even; he’s a pretty prolific guitar player, right? But he didn’t have a massive bag of tricks as far as licks go.

Guys like Albert King, B.B. King, all the blues electric guitar forefathers… Albert had a very limited vocabulary of guitar licks, but it never gets old listening to him because of the amount of feeling he puts into it. So you don’t have to have an endless bag of tricks. It’s just how you implement what you do.

So what can you do differently, or better, now than what you did back on Trouble Is… or Ledbetter Heights — or even The Traveler four years ago?

I think I have a lot more control over my instrument — that’s probably the best way to put it. I certainly have learned a lot and can play things now that I couldn’t play then. That all comes with playing and touring every year since I was a teenager. The more you do that, the better you get.

But intuitively, I’m just being a little more melodic in my playing, a little more vocal in my approach, and just mastering vibrato, which has always been important to me.

In what way has it been important to you?

A lot of young guitar players want to play lead guitar, and they focus on all the notes, and not vibrato, which gives the instrument your voice. I was guilty of that too. And the value of vibrato was driven home to me at an early age.

A family friend showed me a few different ways to do vibrato and said, “This is the most important thing you’ll learn in your guitar playing. That’s how B.B. King can play one note and you know it’s him. Eric Clapton can too.” So I knew about it from a young age and feel like I’ve really developed that over the years, and I have strengths now that I didn’t have then.

Take us into the creative process of Dirt on My Diamonds, which started at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals.

Most if not all of the songs I’ve written over my career have been written in Nashville, except the first album, when I wrote a lot of songs in Louisiana. So my producer, Marshall, and I thought, Let’s do something different and cool and vibey that might actually have a real influence on what we’re doing.

The idea was to go down to FAME with some writers. For probably three to five days — less than a week — we divided into groups and started developing songs.

I’d run into one room and say, “Here’s an idea” and play something for those guys, then I’d run into another room with different guys and start something else and just keep bouncing back and forth between rooms. It was a really interesting experience.

And in a really interesting place.

Oh, man! Being in those studios, in that town. The studio is pretty unchanged. It’s got that original vibe in the walls, in the carpet, in the console and everything. We just went in there knowing that by being there it would have some sort of influence on what we did, but then we let the project happen naturally. My goal the next time we go down there is to record an album as we’re writing.

Would that be for Dirt on My Diamonds Vol. 2?

That one’s already done. We’re fixing and finishing up that stuff, but it’s already done. Now we want to go down there again and write songs and record while we’re writing. Just do a totally different approach to what we did.

What does “dirt on my diamonds” mean?

Marshall felt very strongly that should be the title of the record and the title track. He just thought that song encompasses everything about me as an artist. It’s the blues. It’s rock. It’s fresh. It’s aggressive. He thinks it has one of my strongest vocal performances to date. It has all the elements he thinks represent who I am as an artist.

And the message of the song is kind of timely. The world we live in, with social media and stuff, everything is pushing people to portray this facade of the perfect life and the perfect existence, with all these filters and special effects to make you look a certain way.

But the real beauty is in the imperfections. The fact that we’re not perfect is what makes us interesting and unique, and also gives us something to strive for and learn from. So that’s it. It’s the dirt on the diamonds that makes them really interesting.

What did you use to record, gear-wise?

For the past few records I had Alexander Dumble building the amplifiers. It’s basically the same rig in the studio that I use live; it just depends on how many amps. If I’m tracking, I’m running three.

If I’m overdubbing, I’m probably running five, maybe more. For each song we’ll figure out which will be the featured amp and create a blend with another one or two of the other amps.

[Dumble’s] amps have made such a huge difference for me creatively, ’cause they respond so well to my playing. They do what I want an amp to do much more effortlessly, so that frees me to focus on other things, rather than force an amp to do what I want it to do.

Effects-wise, in the studio I use the real-deal stuff. On the road I bring reissue pedals out. I had an original Klon Centaur on this one, an original Vox Clyde McCoy wah pedal. We had a Uni-Vibe that supposedly belonged to Jimi Hendrix, which is the best-sounding Uni-Vibe I’ve ever heard. I used an Analogman King of Tone overdrive pedal, a TS-808 Tube Screamer and an Analogman Bi-Chorus pedal.

And the guitars?

My ’61 Strat is heavily featured on this record, and so is my new signature guitar. We had just gotten some early prototypes, so I wanted to make sure they went on the record. I used some Custom Shop Strats: the Copperboy and Crossroads.

The Les Paul I used, like for “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting,” that’s a ’90s Custom Shop Gibson a friend gave me for a gift. I just recently bought a 1960 sunburst that I’ve been dying to get; that’ll make the next record.

On “Ease My Mind” that’s actually a new [Gibson ES-] 330; I was in the studio and I called my buddy at Gibson and was like, “Dude, I’m working on this song that needs a 330 and I don’t own one,” so they sent it over immediately.

Did you do anything that you felt you’d never done before on an album?

The solo on “Man on a Mission” has that real open-room sound. The [Fender] Vibroverb amp is just singing on that track. I tried to do more of an Allman Brothers kind of approach there, which is not always where I come from when I’m soloing. And on “Bad Intentions,” that solo and the sound of the guitar is so incredibly gritty. It’s like it has hair on it. It has these big, long bends which I love to do, and it gets me fired up.

Is there a timetable for Vol. 2?

Since there’s a volume one, I would say volume two would maybe be released a year later.

Meanwhile, are the Rides over, or…

Me and Stephen recently did a few things together. He’s like, “Oh, man, I miss you! We need to do this again.” We love each other and we love playing together. It’s just a lot more challenging now, ’cause I’m in Tennessee and he’s in California. It was much easier to get into the car and go to his house and write an album.

But I would say the intention is there; it’s just a matter of can we realistically make it happen with my schedule and his schedule and all the logistics. It was a lot of fun to do, and it would be nice to do it one more time, for sure.

Into the Flame: Kenny Wayne reveals his long search for the perfect ’Burst

What was the last guitar you bought and why did you choose it?

A 1960 Gibson Les Paul Sunburst — an original one. I had been on the hunt for some time, at least 10 years. The thing is, Les Pauls always felt a bit awkward because of my style of playing. I have to adapt my approach with Les Pauls, otherwise I’ll be in the middle of playing and I’ll accidentally hit the pickup selector and change the sound of the guitar mid-solo.

For a long time Strats were the most comfortable guitars for me, but over the course of my career I started using Les Pauls on various songs on various records, and also onstage. Because if you want that sound, you can only get it from that guitar. I found that the features of the 1960 Les Pauls, with the thinner neck profile, just seem to play faster and easier for me.

A year or two ago, I finally found the right one and it’s a beautiful guitar, with a tremendous flamed top and basically the appearance of a ’59, so it has all the good looks you would ever want and a great personality to go along with it. — David Mead

Kenny Wayne Shepherd’s new album Dirt on my Diamonds Volume 1 is available to buy and stream now

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.