Fatten Your Chops With Double-Stops in the Style of Blues Legends Like B.B. King, Lightnin' Hopkins and Robert Johnson

These essential phrases will help you speak the language of blues guitar

A trend popularized by Eric Clapton in the '60s and continued by Stevie Ray Vaughan in the '80s was the slashing, searing, single-note line. Ever since, this has become a cherished goal for all aspiring blues guitar heroes.

But well before Clapton arrived on the scene, blues guitarists were using double-stop lines to fatten up their lead work. In fact, Sylvester Weaver, the first African-American blues guitarist to be recorded, waxed a classic of inestimable importance in 1923 with “Guitar Rag.”

A slide piece in open E, the track depends heavily on harmony in 3rds for the melody and fills. Contemporary lead guitarists would be well advised to follow Weaver’s pioneering example and use double-stops to fatten their chops.

Double-stops often operate in that middle ground between single notes and chords and regularly appear as 4ths, 5ths and 6ths in the blues, although 3rds derived from the diatonic scales are the most common.

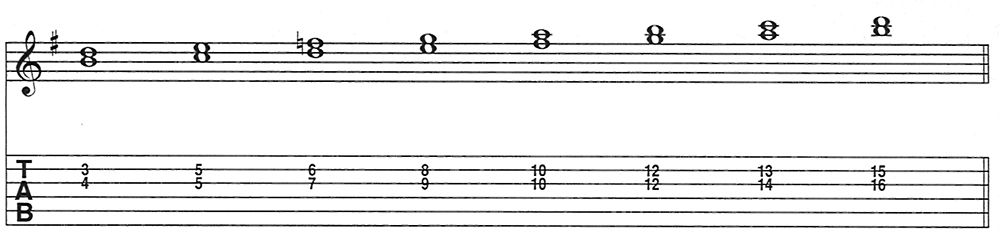

Figure 1 shows dominant-flavored G Mixolydian double-stops on strings 3 and 2, but they may be accessed on any pair of consecutive strings with a slight fingering adjustment.

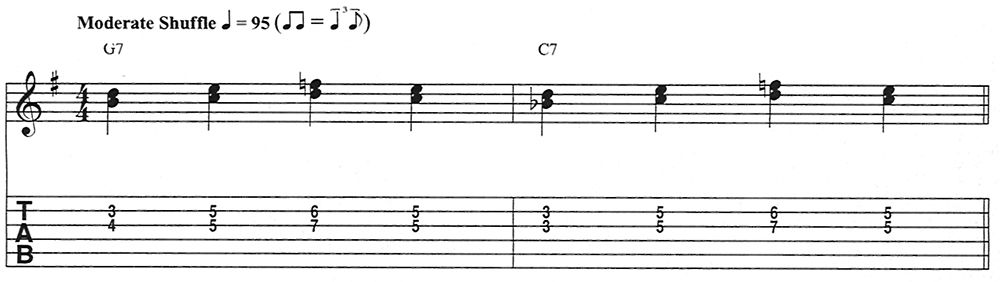

Figure 2 is similar to the head of “Shake Your Moneymaker” as recorded by electric slide deity Elmore James in 1961.

Though it’s slide-based, this is also a hip riff when fingered conventionally as shown, and it belongs in any Blues 101 course.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Dig how merely flatting the major 3rd (B) on beat 1 of measure 1 (I chord) to the b3rd (Bb) on beat 1 of measure 2 (IV chord) – where it functions as the b7th leading tone of C – succinctly indicates the chord change, as the rest of the dyads remain the same.

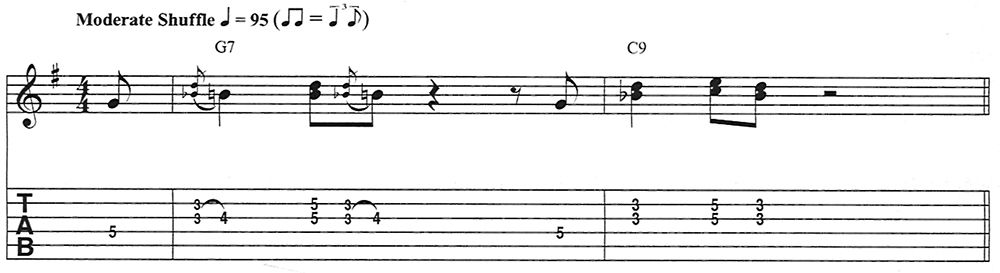

The 3rd-b3rd (b7th) concept is further explored in Figure 3 in one of the all-time classic blues riffs. Countless tunes have employed this form and its variations. B.B. King was a particularly enthusiastic fan of its tonality-defining qualities.

The hammer-on to the major 3rd (B) from D/Bb (5th and b3rd) in measure 1 is the apex of blues cool.

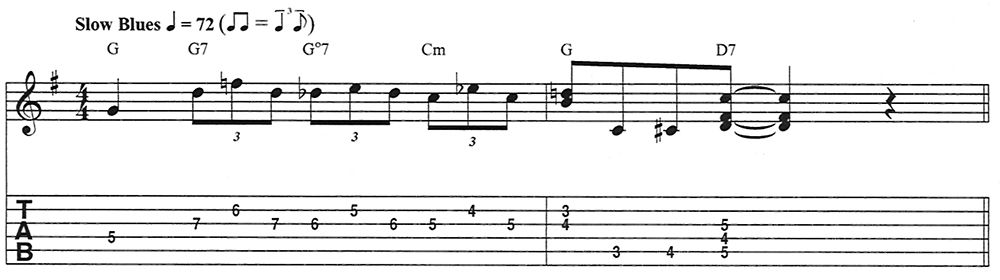

Figure 4 contains triplets implying a dominant 7th on beats 1–3 in measure 1 as favored by the legendary Lightnin’ Hopkins in many of his compositions.

Check out how the chromatic sequence of dyads on strings 4 and 3 in measure 2 implies movement from the G major to G7.

Inasmuch as this device exhibits a strong tendency to move forward to the IV or V chord, it’s suggested that you use it as a turnaround in measures 7 and 8 (I chord) of a 12-bar blues.

Thirds are the building blocks of many turnarounds, and Figure 5 exhibits a typically smooth pattern.

Contributing to this fluid characteristic is the fact that each double-stop contains the same relative interval all the way down the line.

Skip James’ “I’m So Glad” and Robert Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago” both employed variations on this cadence.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.