Grab Your Fender Stratocaster and Get to Grips With Funk Guitar Star Cory Wong’s Dexterous Rhythm Technique

Explore the Vulfpeck and Fearless Flyers maestro's standout rhythm guitar style

If you explore the history of funk guitar, you’ll notice distinctive technical elements among artists known for playing this soulful style of music. The godfather of it all was Jimmy Nolen, who recorded and performed in James Brown’s legendary band in the mid ’60s and laid the foundation for an often-imitated guitar style that others have embraced and expanded upon ever since.

Nolen’s signature style featured a fairly clean and bright electric guitar tone and a syncopated rhythmic approach that incorporated the use of alternate picking and strumming with fretted notes and chords that were typically interspersed with fret-hand-muted strings and “dead” notes, an approach that came to be referred to as “scratch,” or “chicken scratch.”

In addition, he used a handful of dominant-7 and minor-7 chord shapes, or “grips,” that often included upper-structure chord tones, also known as tensions, or extensions, such as the 9th and 13th – what many musicians would label “jazz chords.”

As you move through the decades following funk’s evolution, you’ll encounter other guitarists who further developed the style by applying musical concepts shared by like-minded musicians. The most notable of these are Chic’s Nile Rodgers, Funkadelic’s Eddie Hazel, the Meters’ Leo Nocentelli, the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante, and the late, Minneapolis-based funk-pop music legend Prince, who kept funk rhythm guitar alive and well during the keyboard-dominated pop and new wave music that surged in the 1980s.

More recently, another very talented guitarist from Minneapolis has been strumming up a lot of attention with his unique brand of modern funk music: Cory Wong of Vulfpeck and Fearless Flyers fame. A prolific artist, Wong has consistently released exciting music with these bands and various collaborative projects over the past decade, as well as inspired solo material.

The uniquely freaky guitarist is revered for his resourceful chord vocabulary and keen rhythmic prowess, as well as his technical, stylistic and tonal hallmarks, such as his dexterous pick-hand “helicopter” strumming technique, slinky single-note riffs and phrases, sparse and melodic soloing and his penchant for using his Fender Stratocaster’s position-4 pickup selection, which pairs the neck and middle pickups together, out of phase.

Wong is also a thoughtful improviser who enjoys playfully pushing whomever he’s playing with to greater creative heights. His inspired performance ethic harnesses a genuinely thrilling energy level and couples it with a spontaneous, off-the-cuff feel in both the recording studio and onstage.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

If you’re new to funk rhythm guitar, there are plenty of things to discover and learn about the style by studying a player like Wong and the key musical elements found in his music. The first concept you should become aware of is what’s known as “the three S’s of funk”: strum, scratch and slide. As you begin exploring the style, you’ll find that the majority of classic funk rhythm guitar parts feature at least two of these elements. The strumming aspect is rather obvious and refers to heartily strumming the strings in an alternating down-up-down-up motion with a flat pick, although this may also be done with the bare fingers.

Once you add muted-string “scratching” to the mix – performed by strumming the strings while momentarily loosening your fret hand’s grip on a chord shape to dampen the strings and replace the notes with pitchless, percussive “chucks” – you’ll find that it imparts an authentic rhythmic and percussive edge to the music.

Finally, the slippery shifting and sliding movements between chords, such as sliding into a chord from one fret below, adds another style element to the music and a distinctly soulful sound.

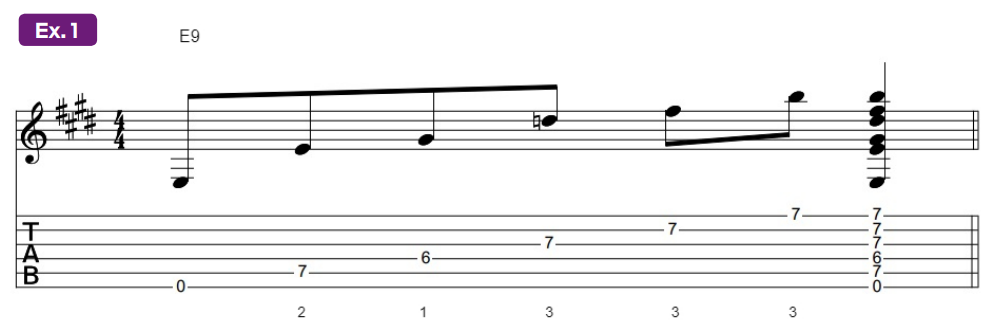

As you begin blending these three factors, you’ll arrive at a sound that definitively epitomizes funk rhythm guitar. The first funk chord one should learn is that which is most often used and heard in the style and considered the signature funk chord– the dominant 9, which is a dominant 7 chord with a major 9th added, theoretically and intervallically spelled 1 (root), 3, 5, b7, 9. In the key of E, that would be E9, spelled with the notes E G# B D F#.

Ex. 1 shows the most widely used fingering and voicing for this chord, played across the top five strings in 7th position. Notice that the 5th of the chord, B, is voiced up an octave from its theoretical spelling within the chord formula and becomes the highest note, above both the 9th, F# and flatted 7th, D.

Once you have a feel for this chord shape performed in its full five-note incarnation (not including the open low E note, which is added here only because it happens to be available as an octave-doubled root note in this key), the next step is to learn partial forms of it by stripping the chord down to its bare minimum and focusing on the essential upper-register notes.

Compared to other musical styles, such as rock, metal or country, guitar in a typical funk rhythm section plays a more rhythmic and percussive role. It’s heard primarily in the background and integrated into a supportive groove with the bass and drums. Funk guitarists often find a place, or niche, to thrive within the blend of other instruments, and this is in stark contrast to the electric guitar’s role in other styles, such as rock, where it’s typically one of the sonically dominant instruments.

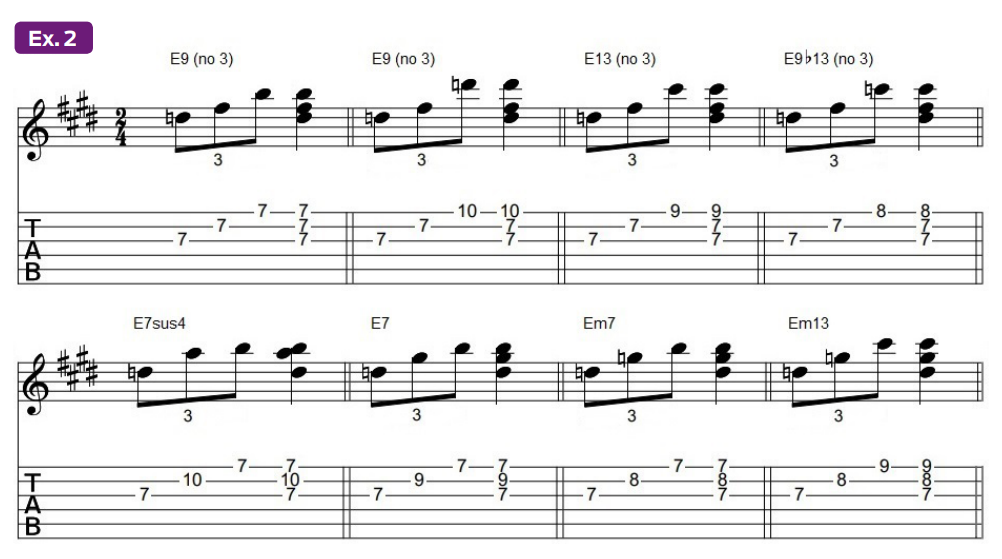

In funk, the guitar is more of a community or ensemble instrument and placed into a secondary role which is nonetheless musically important, to say the least. With this in mind, you’ll find that most funk guitarists, such as Wong, choose to strip their chords down to the essential notes, typically two- and three-note shapes played on the higher strings.

Wong estimates that he uses partial chords in his music “90 percent of the time,” and notes that they are commonly arranged along two or three adjacent strings and rarely on the A or low E. This “stripped,” upper-register approach allows the guitar to sit in the mix with other instruments clearly and effectively while leaving plenty of sonic space for the bass, keys, horns and/or another guitar to fill.

As you’ll see, when it comes to playing funk guitar, oftentimes less is more. Ex. 2 presents, in the key of E, an assortment of useful funk-style partial chord voicings on the top three strings. Notice in each case that the E root note is not present, as the root is often played only by the bass in this style.

Wong will form each of these chord grips with a foundational partial barre across the top three strings at the 7th fret, as with the previously demonstrated five-note E9 chord. Here, however, the 1st finger is used for barring, rather than the 3rd, freeing up the other fingertips to fret various harmonic-melodic extensions on the G, B and high E strings. These partial chord variations will help you access an assortment of popular and useful funk rhythm guitar sounds. Once you’re familiar with this collection of partial chords, you can begin experimenting and creating a few basic riffs and short, repeating rhythm patterns that combine the chords in various combinations.

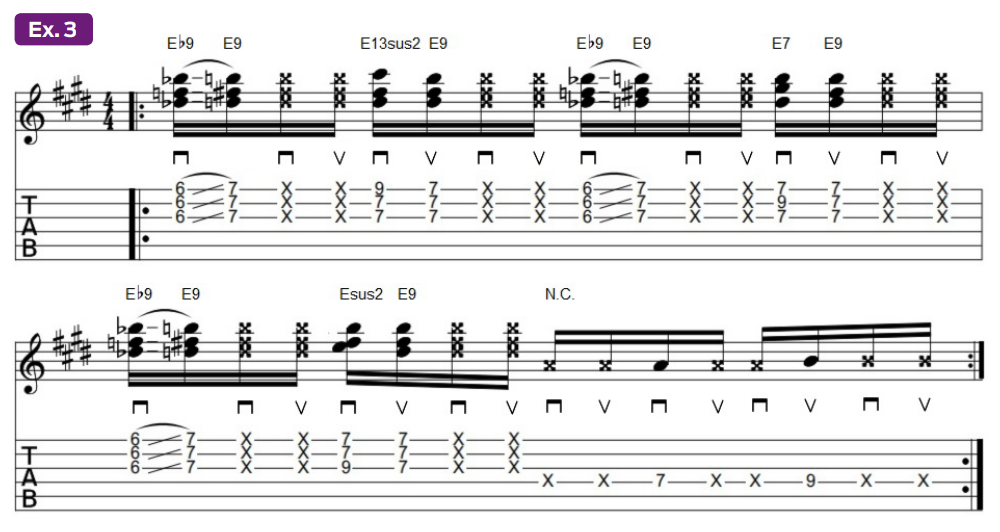

Ex. 3 is a repeating two-bar funk rhythm exercise that demonstrates some ways to mix and match these various partial chord types. As the example unfolds, notice the use of fret-hand muting (indicated by the Xs), how the 1st-finger barre slides from the 6th fret to the 7th and extends over to the D string for the single notes at the end of bar 2, and the way notes are added with the 3rd finger at the 9th fret on each of the strings during different beats.

You should also notice how “the three S’s of funk” are in play here. This kind of mixture of partial chords and single notes is very common in funk rhythm playing, and this figure illustrates the concept in detail.

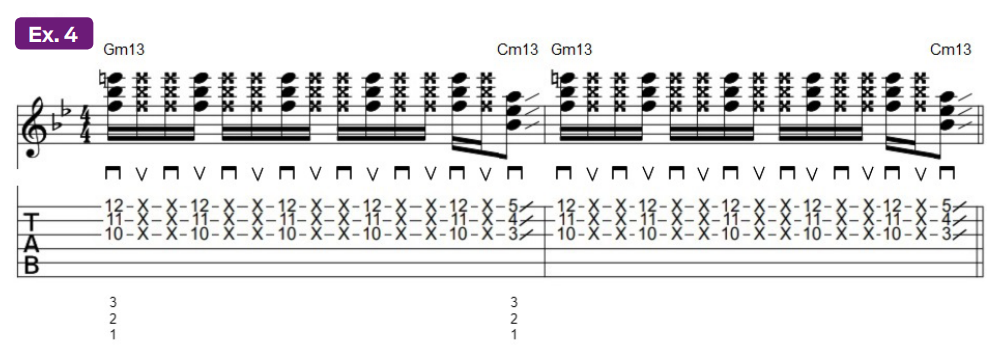

A great example of this type of playing in Wong’s music can be heard in the ultra-funky track “Jax,” from his 2018 release, The Optimist. Ex. 4 offers a “scratch” rhythm figure similar to one Wong plays in the song and targets a bitingly dissonant Gm13 chord played in 10th position, which is the same Em13 grip we looked at in the previous example, shifted up three frets.

This one features what may be thought of as a “rhythm within a rhythm,” as the fretted chord strums create a syncopated accent pattern when interspersed among all the fret-hand muted scratches that surround them within the steady 16th-note down-up-down-up strum rhythm.

Also notice the way the long slide from 3rd position at the end of each bar nicely punctuates the phrasing with a brief iv-i chord change in the key of G minor (Cm13 to Gm13).

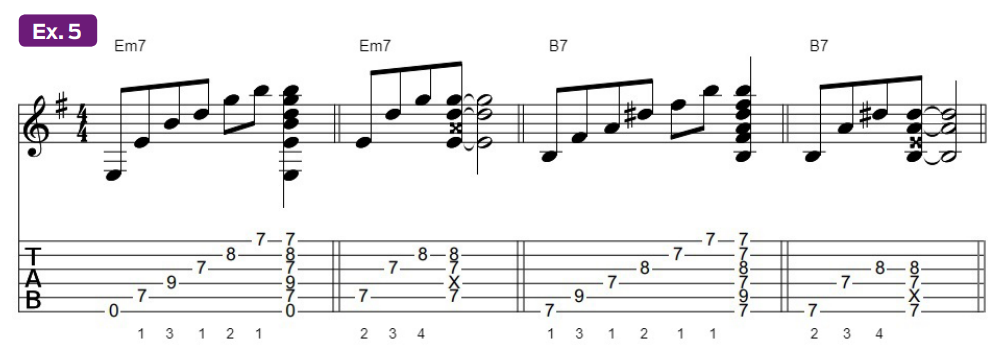

Another area of Wong’s funk chord-playing expertise includes his knack for employing chord fingerings that intentionally remove notes from full barre-chord forms to create sparser three-note “shell” voicings, as these often work better in many situations than strumming full barre chords, which can sound too thick and overbearing.

Ex. 5 illustrates two ways in which he’ll do this with 5th- and 6th-string-root chords, using two standard chord types, Em7 and B7. The Em7 chord in measure 1 is initially performed as a traditional five-note barre-chord fingering, as is the B7 chord in measure 3.

Each voicing is then followed by a sparser three-note variation that only includes the root, 7th and 3rd.

Notice the physical and visual similarity between the two sets of chord shapes and the way each fretted note shifts down to a lower string when moving from Em7 to B7. But due to the guitar’s asymmetrical tuning, the first two chords are minor 7s and the next two are dominant 7s. If you watch Cory perform, you’ll see him frequently using these kinds of sparse, wide-interval voicings.

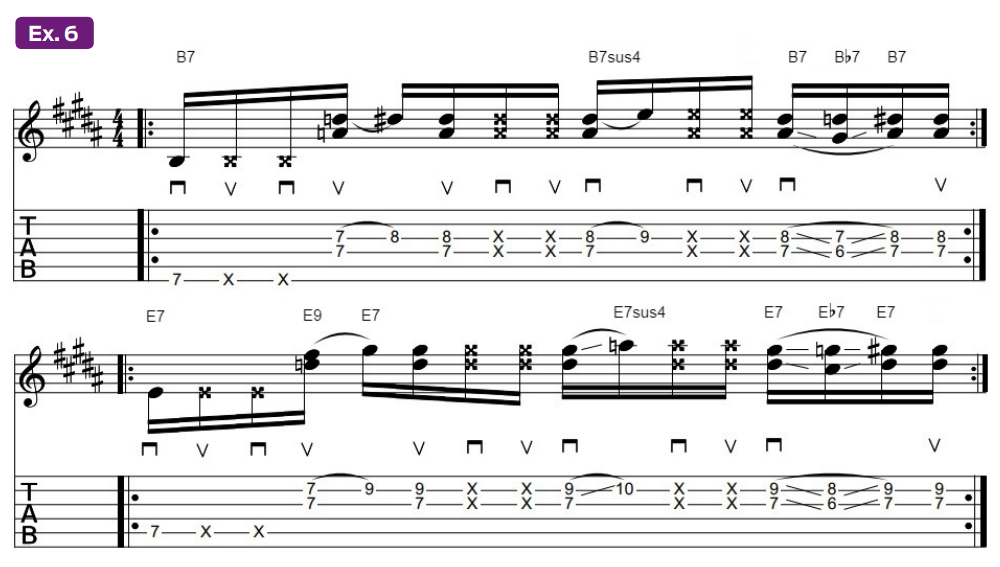

To further demonstrate how to apply a few of these kinds of partial chords in a funk rhythm pattern, Ex. 6 presents a repeating two-chord vamp that challenges your fingers and brain, in terms of deciding how to finger each chord extension and reach the highest note with a minimal amount of stretching.

You’ll see that we’re essentially moving between B7 and E7 here – a I7–IV7 progression in the key of B major – with some bluesy hammer-ons and slippery double-stop slides applied to the foundational chord shapes. These kinds of embellishments are common in funk rhythm guitar playing and are a crucial element of Cory’s personal style.

It should be noted that, although Wong often employs sparse partial chords and shell voicings, he certainly isn’t a “chord slouch” and at times also uses traditional full-chord fingerings and voicings in his writing.

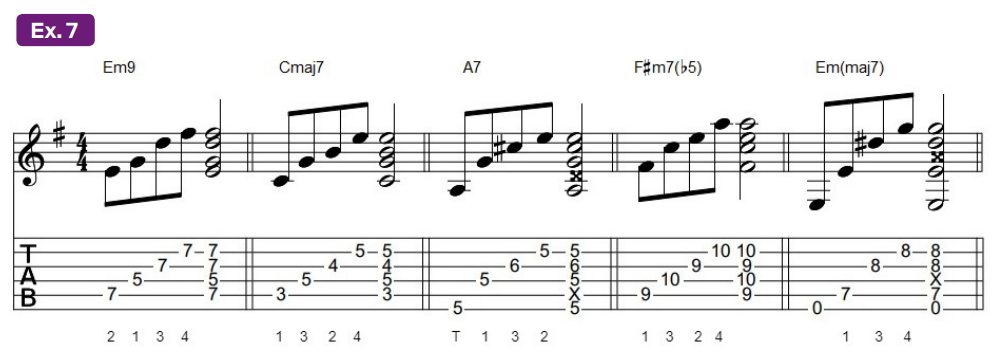

Ex. 7 outlines a jazz-influenced progression not unlike that heard in “Cosmic Sans,” from the guitarist’s 2019 solo album Motivational Music for the Syncopated Soul.

As you play through the sequence of chords in this example, notice that the progression includes several common four-note voicings and fingerings and how, when they’re strung together in this manner, they create a decidedly jazzy feel, although the underlying funk groove and laid-back flow of the song that informs them are very much in the funk style.

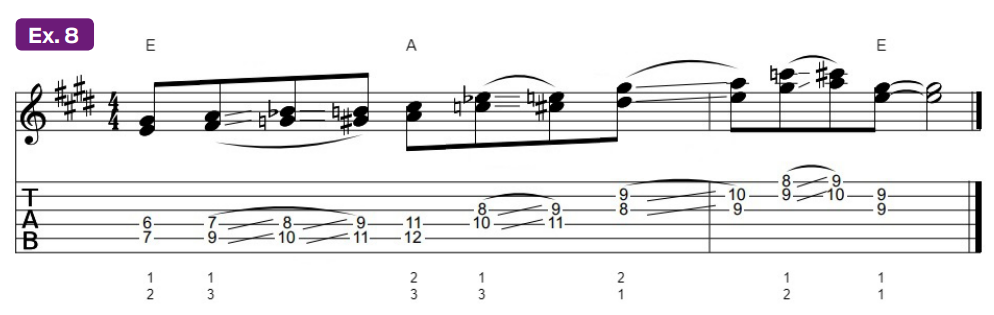

Another interesting aspect of Cory’s funk playing is the way he’ll use double-stops to harmonize a melody line in intervals of thirds and fourths. Ex. 8 offers a demonstration of this type of playing, inspired by “Side Step,” from his 2017 album, Cory Wong and the Green Screen Band.

Notice how the double-stops slide up the strings in a parallel manner while effectively outlining an underlying E–A chord change in a tastefully melodic way.

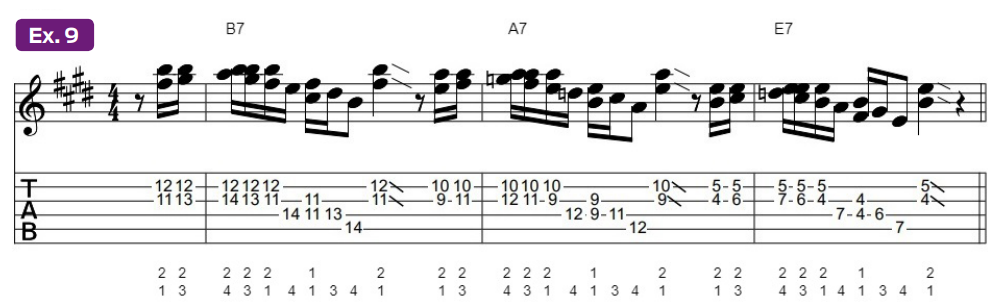

Also inspired by Wong’s riff writing style, Ex. 9 features a melodic motif that soulfully outlines a V7–IV7–I7 progression in the key of E major (B7–A7–E7) with a sequenced one-bar riff that’s built around double-stops and shifts down the neck as it is applied to each successive chord, using the same rhythmic phrasing and melodic contour each time.

Shared, or recycled, fingerings like this are of course found in other styles of guitar-driven music, but you’ll find this kind of “riff-relocation” occurring often in funk.

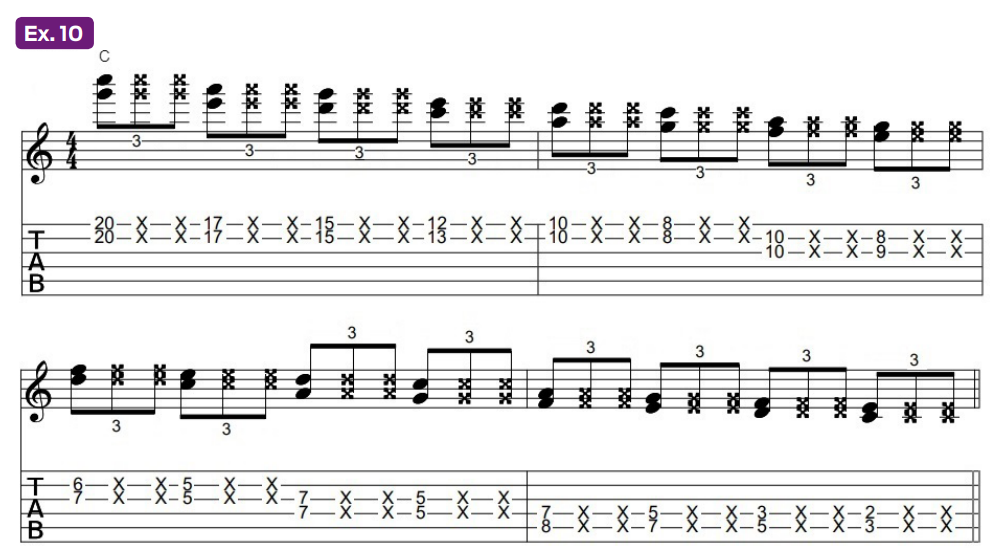

Our final offering, Ex. 10, illustrates another musical idea frequently heard in Cory’s playing – the use of double-stops and “scratch” strums with an eighth-note triplet rhythm and groove – and brings to mind a similar figure featured in his song “Companion Pass,” again from Motivational Music for the Syncopated Soul.

As you play through the phrase, notice the descent down and across the strings and the use of various double-stops with 4th and 3rd intervals based primarily on the C major pentatonic scale (C, D, E, G, A, intervallically spelled 1, 2, 3, 5, 6), with the addition of the 4th, F, which creates a C major hexatonic sound (C, D, E, F, G, A).

This kind of throaty double-stop triplet phrasing is another signature element of Cory’s playing and writing style, and you can also hear it in plenty of other musicians’ music too, in such genres as pop, soul, R&B, jazz and rock, as well as funk.

This glimpse into Cory Wong’s guitar playing style is by no means complete, as far as uncovering the various musical elements and surprises featured in his body of work. From intensely savage riffs and rhythms to jazzy textures and rock sounds, the talented musician can seemingly play whatever he wants.

At this stage of his career, he seems more than content reminding the listening public of how interesting and inspiring funk music can be while injecting his musical thumbprint and identity onto the style as his career progresses. Needless to say, if you’re unfamiliar with Cory Wong and his music, you have a lot of worthwhile listening to do. It’s a fun ride with plenty to see, hear and learn along the way.