“If I Can Get That Live-Performance Spark Across in the Studio, I’m Very Happy”: Richard Thompson Talks Songwriting, Self-Production and His Fast-Paced Approach to Recording

Following the release of his latest solo album, ’13 Rivers,’ the guitarist spoke to ‘GP’ about his creative process and how to put together the perfect Frankenstrat

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

***This article originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Guitar Player***

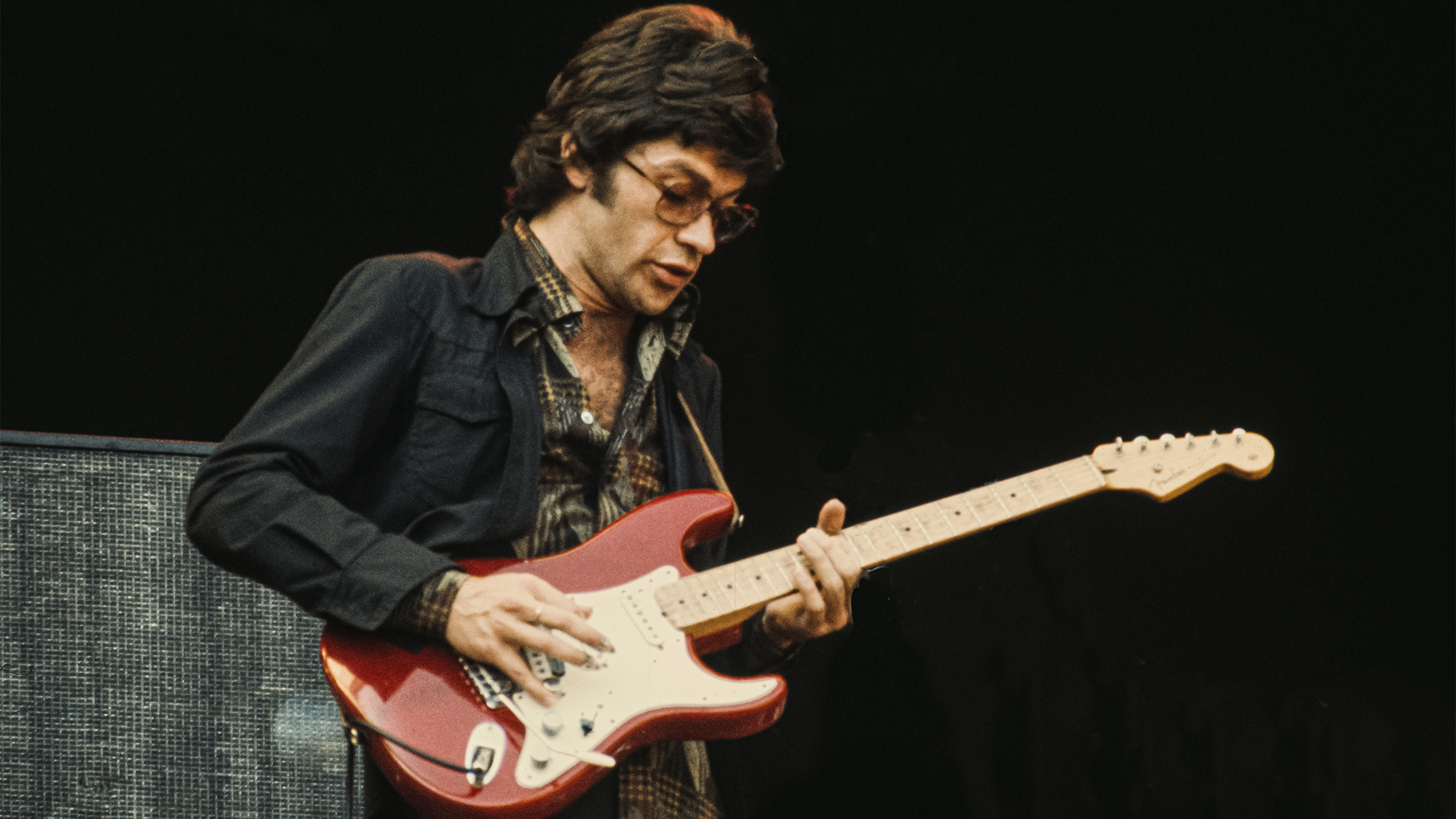

Throughout more than five decades of music making, Richard Thompson has been a sublime, famously confessional artist who treads unafraid into the dark, hellish twists of earthbound existence.

Critics and fans typically adore him for his poetic bravery, and journalists tend to get all “literary” describing his work in suitably important prose.

He absolutely deserves all the accolades, and, yes, it must be frightening for any writer to try to describe Thompson’s enduring and transcendent talent using the same vocabulary one might deploy to make sense of 5 Seconds of Summer’s bazillion YouTube views.

However, the Richard Thompson discussing his latest album, 13 Rivers (New West), seems so removed from a half-century of hero worship and often-exuberant critical acclaim. He is polite and open, devoid of artistic or egocentric pretension and appears quite happy in an engaging, just-one-of-the-peeps-making-sense-of-the-planet kind of way.

Even in his own press for 13 Rivers – his 19th solo album – he poo-pooed the myth making surrounding his songwriting prowess by stating, “I never really think about what songs mean. I just write them.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And although he is a guitar hero, he doesn’t act like one. He comes off as a guy who simply loves to play. Someone who is still hungry, still chasing innovation and still excited about guitar sounds and gear.

At an age where some artists seem content to revisit past glories, he continues to surrender to his gut and plunge boldly into the uncharted joys of improvisation. So although much has been written about Thompson’s guitar playing, if you think you know what to expect from his red Stratocaster on 13 Rivers – well, you ain’t heard nothing yet.

Did you plot 13 Rivers as a conceptual journey, or did the songs emerge as individual pieces and you discovered the concept when the material was completed?

It was more the latter. I wasn’t thinking too much about the kind of record I was going to make, or even what kinds of songs I wanted to write. I sort of just “arrived” at this record. I’d be playing at home, and tunes and lyrics would turn up.

I was unaware of the process, and, at the end of it, I found myself saying, “I understand the emotion of the song, but why did I write it this way? Why did I use this theme to express this idea?” There were a lot of surprises.

When an idea first beams into your brain, how do you typically mold that idea into a song?

There’s absolutely a refinement process. Sometimes that process extends all the way to the recording sessions and all the way into the live arrangements

Richard Thompson

After the initial inspiration, I look at it and say, “This is one verse too many,” or “I need a better rhyme for verse three.” There’s absolutely a refinement process. Sometimes that process extends all the way to the recording sessions and all the way into the live arrangements.

For this record, we’d listen to the tracks and go, “Perhaps we shouldn’t do that. Let’s try this bass line or that rhythm figure.” It’s a shorter refinement process because the clock is ticking, but things can still change in the studio.

The refinements don’t necessarily stop when you start playing the songs in concert, either. Usually, the audience will let you know if a song is lacking something by the way they respond. You can feel how much you’re getting across, and whether the song needs to be tweaked to communicate better with listeners.

Throughout your career, you’ve produced your own albums, and you’ve also worked with outside producers. What drove the decision to take on the production of 13 Rivers yourself, rather than collaborate with someone else?

We did have a producer earmarked for this project, but he dropped out fairly late in the day. So I thought, Well, the studio is booked, the musicians are booked, and I know how to produce a record. I’ll do it, and we’ll see what happens. I think it turned out well.

How does your creative process unfold when you collaborate with a producer that’s not you?

I prefer accidents to happen in the studio, and I think if you produce yourself all the time, things get predictable

Richard Thompson

Different producers bring different things to the table, and it’s good to change things up. They’ll hear different things and bring in ideas you may not have considered yourself. In fact, what other people bring to the process is sometimes more interesting to me than the way I conceived it.

But it’s nice to produce yourself sometimes, because the original vision you have for the record becomes fulfilled in a purer way, and your ideas get seen through to fruition.

You can be authoritarian, and say, “This is the way I hear it in my head. It has to be this way. You’re the musicians, and you have to bend to my will.” Sometimes, that works tremendously well – especially if you have a strong and clear creative vision. But I prefer accidents to happen in the studio, and I think if you produce yourself all the time, things get predictable.

You tend to record your albums almost superhero quick. This one reportedly took just 10 days start to finish.

I think I’ve always worked at a fast pace. In the old days, it was a financial necessity to get through the sessions as fast as possible without cutting corners. If you have musicians who are very good in the studio, you can do that. Also, I think if you record fairly live, making an album shouldn’t take that long. That’s what we do. We don’t overdub very much.

People work in all different ways in the studio. Some can be very slow and methodic, and that works great for them. Someone like Mutt Lange [producer of AC/DC, Def Leppard, Foreigner and others] will record one drum at a time. For me, I find if I labor over it, it just doesn’t sound as good. It sounds less spontaneous, and it sounds a bit dull. If I can get that live-performance spark across in the studio, I’m very happy.

Is there a technique to orchestrating quality and speed in the studio? Do you do a lot of pre-production before you walk in to record?

Not really. The band [drummer Michael Jerome, bassist Taras Prodaniuk and guitarist Bobby Eichorn] has a way of playing together that has been established over the last 10 to 20 years, so I think we just look at what’s in front of us and we respond.

Most things are recorded in the first two or three takes

Richard Thompson

We don’t slavishly go over anything that much. I send home demos to them to give them an idea of the songs, but I tell them to not fall in love with the demo. I want them to keep open minds so that interesting things can happen in the studio – those happy accidents.

Most things are recorded in the first two or three takes, although you sometimes get the redheaded stepchild of a track that refuses to settle down. You might spend a lot more time on that one.

On this record, everything went smoothly – which doesn’t always happen. In that sense, it was kind of a lucky record, because we didn’t hit any walls.

I love that spell-like tom groove on “The Storm Won’t Come.” Was that part documented on your home demo, or did it emerge from one of those happy accidents in the studio?

I’m trying to remember what actually happened! I think the general groove was present on the demo. Michael started to play the toms, and it became kind of a reverse Bo Diddley thing that fit the track.

We also overdubbed a Hammond organ. You can barely hear it, but it has this deep throb that builds the feel of the song. It starts really spare, and then pushes into this whole stormy atmosphere.

It’s either interesting repetition or it’s boring repetition. It’s a fine line between the two, and you have to be careful which is which

When you’re creating something that’s a slow burn like “The Storm Won’t Come,” there’s that point where the song either becomes spellbinding or boring. Your song does weave a spell, so how did you achieve that effect?

I’m not sure it’s something you can describe. Creating a track that’s hypnotic usually means repetition of some sort, and it’s either interesting repetition or it’s boring repetition. It’s a fine line between the two, and you have to be careful which is which.

Ultimately, it’s up to the ears of the beholder. Some people have said the guitar solo at the end of “The Storm Won’t Come” is quite interesting, but otherwise they’re pretty bored by the whole thing.

Did you use alternate tunings?

Everything is pretty much standard. Apart from drop D, I hardly ever use alternate tunings on the electric guitar. A song like “Her Love Was Meant For Me” is in the key of D, so it was logical to tune to drop D for a fuller sound.

Did you create any guitar riffs that sounded so good in a specific key that you kept it as written, even though it might have been too high or too low for your voice? I talk to players all the time who get hemmed in by riffs they love and don’t want to ruin the vibe by adding a capo or revoicing anything.

That is a very annoying thing. Many times, something fits perfectly on the guitar, and you think, This is great, but I wish it was in an easier key for me to sing.

The solos were usually improvised live in the studio without too much forethought, and some of them were a first take

Richard Thompson

In fact, there’s a track on the album that is really too high for me, but I kind of plowed through it. To me, it sounds a little strained, but no one has commented, so I’ll keep my mouth shut.

Your solos on this record are absolutely ferocious and, at times, astounding in what you throw at the listener – unexpected bends, dissonant notes and so on. It sounds as if you’re improvising, but maybe you pieced those together.

No. The solos were usually improvised live in the studio without too much forethought, and some of them were a first take where I hadn’t even settled into the song.

I might have fixed a couple of things here and there, but it’s mostly just reacting to the song in the studio as it goes down – which is often the best way. You get this spontaneous response to what the other musicians are doing, and there’s a freshness that becomes harder to reproduce after you’ve played something 60 times. [laughs]

Have you always taken this approach to soloing?

Over the years, I’ve done some good solos that were overdubbed and glued together later. But it was never, “Let’s take this phrase here, and this phrase here, and these other 20 phrases and build a solo.”

I don’t like leaving things to fix in the mix. I’d rather just go for it, mistakes and all, because that approach sounds better to me

Richard Thompson

It was more common to go, “The front half of this solo is great, and the back half is great, so let’s find a way to glue the two together.” Sometimes, that approach can create something extraordinary. But, on the whole, I go for it live every time I can.

I like to think of this as “front-end” recording, where you make the choices as everything is going down. If you mess up, or if there’s a technical problem, you immediately do it again. These are front-end decisions, as opposed to going, “We can fix this later in Pro Tools.”

I don’t like leaving things to fix in the mix. I’d rather just go for it, mistakes and all, because that approach sounds better to me. And there are loads of mistakes all over this record. But I think they’re creative mistakes, the kind you’d have on songs in the pre-multitrack era, where musicians were putting down a performance: “Oh, take one didn’t work? Okay, let’s try a take two.”

Do you tend to be loyal to the solos you create in the studio? Some artists consider their recorded solos to be essential elements of a song, and they tend to “stick to the script,” so to speak, when they perform live.

I don’t consider any of the performances on the album to be etched in stone. A record is a record. It’s a recording of a moment. But when you perform the songs live, every night can be different. You’re pushing in a different way and looking for different things.

My listeners will buy the album – that’s great and thank you very much – but I think a lot of them prefer my live concerts, because different things are going to happen. Sparks can fly!

I listen to what everyone else is doing, and then I ask myself, What tone will sit in the track for this song properly?

Richard Thompson

How did you dial in your guitar tones?

For the most part, I listen to what everyone else is doing, and then I ask myself, What tone will sit in the track for this song properly? I have a basic tone that I use as a fall back, but I like to try different sounds and textures in the studio.

Sometimes, new directions present themselves. For example, the engineer on the record, Clay Blair, is a Beatles nut. He has clones of the Beatles studio stuff – all the EMI compressors and microphones – as well as clones of every instrument the Beatles used at Abbey Road in the 1960s.

So there were all these guitars on the wall, and I would say, “I want to get a different tone on this track. I’ll use the Epiphone Casino.”

I assume the basic tone you mentioned is driven by your Stratocaster?

Yes. It’s a red Strat, a kind of a Frankenstein of a guitar. Bobby Eichorn – who is also my guitar tech, as well as co-guitarist in the band – assembles them for me. He finds bits and pieces and throws them together. They’re usually wonderful guitars that play really well and sound great.

Does Bobby use Fender parts exclusively for your Strats, or does he pull pieces from different brands to put something together?

You have to match the pickup to the body resonance. There’s a kind of science to it

Richard Thompson

I think it’s mostly Fender, but in many cases, it isn’t. He just finds the things that work best for the kind of attack I use when I play.

Obviously, he knows you quite well, so he’s aware of exactly what to look for in a neck and things like that.

Exactly. For example, the weight of the body is incredibly important. All the classic Strats from the ’50s – the really good ones – had body weights that fell between fairly narrow parameters. Then you have to match the pickup to the body resonance. There’s a kind of science to it.

I actually think my current Strat sounds better than my ’59 Strat, which has been restored and is now playable again.

I have to ask, why not just go to a music store and look for the perfect Strat right off the rack?

Fender is a big company that makes a lot of instruments. You can go into Guitar Center and play 20 Stratocasters, and they will all have different virtues – different sounds, different playability, different outputs and so on.

We just start the process by saying, “Let’s find the best neck and the best body for the pickups I want to use.” That way, we can get something much closer to precisely what I’m looking for.

Do you still use your Lowden F-35C signature model for acoustic stuff?

That’s pretty much the only acoustic guitar I use. For some straight rhythm parts, I might use my Gibson J-200.

What amps did you plug into for the album sessions?

I used a Divided by 13 – which is also my favorite stage amp – a fairly old Fender Deluxe and a Vox AC15.

How would you choose one of those three amps for a specific song or part?

Any choices were just for slight variations in the sound. The Vox is a little bit ping-ier than the Divided by 13, so it works better for some things.

But if I could find one great sound that’s full and clean, but also punchy and has a little bit of compression to it, then, boy, I’m really happy.

I’m a little suspicious of amps that have 15 different sounds on them.

You’ve been loyal to the Divided by 13 for quite a while. What is it about that amp that you like so much?

It has a full range sound that’s something like a Fender Deluxe, which is a great recording and live amp.

The Divided by 13 is a little fuller in the bass than the Deluxe, however, and it has a little more tonal versatility. It’s basically a Fender and a Vox glued together, so you can pick from whichever channel is the right sound for the job, or you can blend the two channels together, which is mostly what I do with the amp.

It also has mismatched speakers – a Celestion Blue and a Celestion Green – which gives you different tonal possibilities, because you can use one or both speakers.

I loved the subtle and not-so-subtle changes in your overdrive textures from song to song. How much of the drive is from pedals and how much is from cranking up the amps?

It’s mostly pedals. I used the Fulltone OCD a fair bit. I brought my live pedalboard into the studio to change up the sounds a little.

Do you mind going through what’s currently on that board?

I’ll try. [laughs] The OCD is there, of course, as well as a Carl Martin Red Repeat, a Fulltone Deja ’Vibe Tremolo, a Sweet Sound Mojo Vibe and a Divided by 13 Switchazel.

As an extremely accomplished songwriter, are you like an Ernest Hemingway, who had a more-or-less specific methodology for writing his novels, or do you find songs in any way they want to beam into your brain? Specifically, do you keep notebooks of lyrics awaiting some music, do you write music and seek out lyrics, or do you focus on a song until the words and music happen organically and simultaneously?

It’s all of those things and more. It’s nice to be open and not work the same way every time. I like the fact that a song can start with lyrics or the music. Or everything can come at once – which, believe me, is a dream come true.

Richard Thompson is currently on tour in North America. Visit his website for more info, further dates, new releases and more.