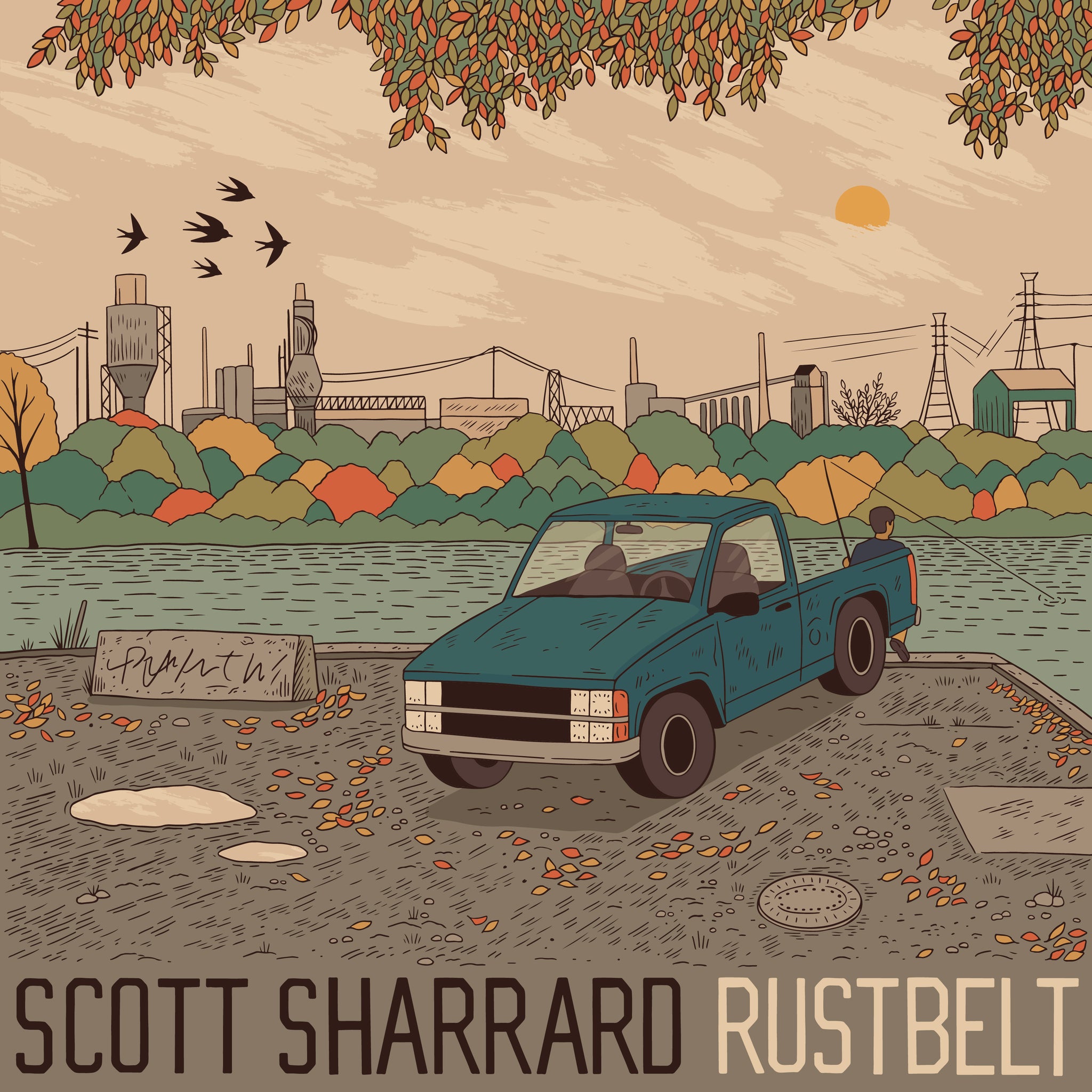

“I Did This One for Me. This Was a Bloodletting”: Scott Sharrard on His New Watershed Album, ‘Rustbelt’

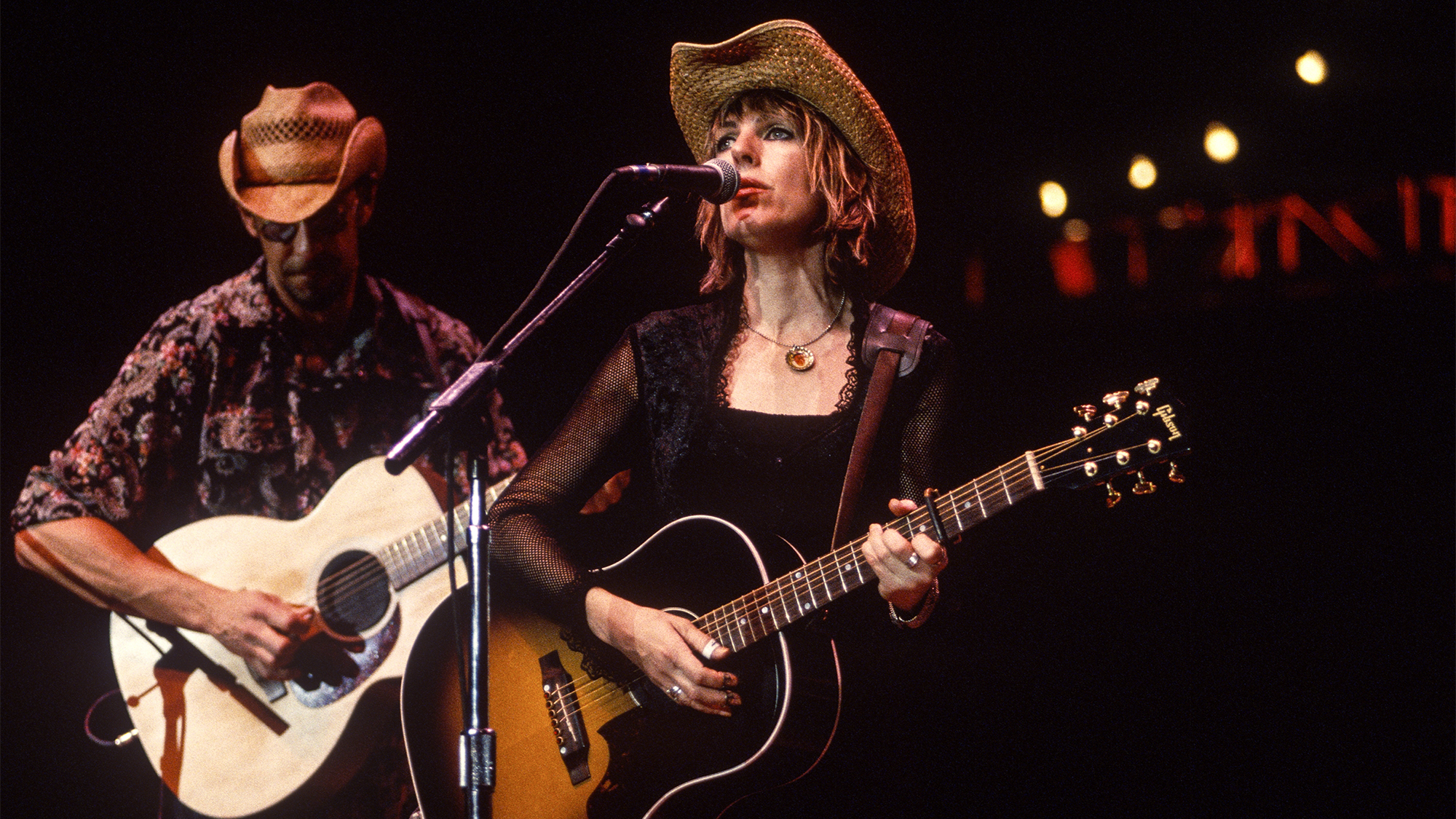

After making his mark with Gregg Allman and members of the Band’s camp, the Rust Belt troubadour now takes his place in Little Feat while dropping a solo album infused with his Midwest roots.

Scott Sharrard has no shortage of talents. The acclaimed guitarist, singer, songwriter and bandleader likewise has no dearth of providence. He was born on the very day his future lodestar, blues virtuoso Freddie King, died. Sharrard’s father, himself a guitarist, guided his son, exposing him to the Allman Brothers Band, the Band and Little Feat. Sharrard would describe these experiences as “Big Bang moments."

In the years ahead, he built generational bridges to his triumvirate of top groups, and they beckoned to him. After studying music in Milwaukee and developing his chops, Sharrard formed a band with Gregg Allman’s saxophonist Jay Collins, resulting in his becoming lead guitarist from 2008 to 2017 with the Gregg Allman Band.

Thus, the first plank was set. Sharrard formed the second plank by establishing the CKS Band with keyboardist Bruce Katz of Allman’s band and drummer Randy Ciarlante of the Band. He had the honor of playing at Levon Helm’s farewell concert, and Helm’s daughter Amy has regularly sung with Sharrard, especially his Brickyard Band.

He has now laid the third plank by joining Little Feat while forging a bridge to his Midwest roots with his new album Rustbelt, an Immediate Family Records release.

Sharrard spoke with Guitar Player to trace out his journey and discuss the road up ahead.

What prompted your passion for Little Feat?

It was my dad playing their songs at home. Their album Waiting for Columbus grabbed me when I was eight. In 1988, I saw them during their Let It Roll tour and on Saturday Night Live.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I admired their flawless blend of different styles of American music, their unique mix of heartfelt ballads and gonzo, Mad Magazine-type boogie stuff. They also had big Band influences, especially with how co-founder Bill Payne innovatively used synthesizers. Songwriting was crucial for them. Their lyrics hit me where it counts.

Now you’re branching out to another band in your pantheon. How did this occur?

I met Bill sitting in with the Doobie Brothers while touring with Gregg. Eventually they adopted many people from Gregg’s camp: our tour manager, sound guy and percussionist Marc Quinones. Little Feat’s singer/songwriter/bandleader Paul Barrere became ill in 2019 and couldn’t do a couple of tours. Larry Campbell, formerly musical director of the Levon Helm Band, and his wife, singer Teresa Williams, were booked to open for the band but couldn’t perform the last two gigs. Bill asked around the Doobie Brothers camp; Tom Johnston, Pat Simmons and Marc recommended me.

I did the first show the day Paul died. That was tough. I rose to the challenge and gave a worthy performance on their behalf

Scott Sharrard

I did the first show the day Paul died. That was tough. I rose to the challenge and gave a worthy performance on their behalf. Afterward, they said, “You’re in the band now.” It was Paul passing me the baton from beyond.

I’ve already played six gigs with Little Feat. I haven’t wiped the smile off my face. We’re about to tour, celebrating the legacy along with a fresh lineup. We’ve been writing a lot and preparing a new album.

Is there a bridge between the Brickyard Band and Little Feat?

I assembled the Brickyard Band as a modern Little Feat, just as diverse and cohesive. Singer/songwriter Moses Patrou was my inspiration. We became friends playing with Jay Collins, who also played with Little Feat and Gregg.

I always wanted to be in a band with another singer/songwriter in it. Moses is also a percussionist, drummer and keyboard player. The Brickyard Band was five guys sounding like eight. Little Feat was my template when making [2012’s] Scott Sharrard and the Brickyard Band.

Which guitars do you use with Little Feat?

Little Feat requires its own scenario. I’m trying to complement guitarist/trumpet player Fred Tackett, who has been with the band since the ’80s. Fred has a remarkable guitar style, not only evident with Little Feat but also on records with Rickie Lee Jones, Bob Seger and Tom Waits, to name a few.

I also need the sound of Barrere and Lowell George, the band’s other co-founder. To achieve this, I got a couple of Stratocasters for slide. Formerly I played slide in standard tuning. With Little Feat, I’m playing mostly in open A, like Lowell, and a couple of songs in open G.

I got my new Heritage H137 guitar, made in the original Gibson factory in Kalamazoo. It’s like a Les Paul Junior with two pickups. I’m using that for standard tuning. I have my Custom Shop standard-tuning Gibson CS-336 circa 2002 with OX4 Pickups, the guitar that I’m mostly associated with, the one I played live with Gregg.

What are your gear preferences?

To achieve Little Feat’s slide sound, you need a unity gain compressor. Origin Effects makes a pedal called a SlideRig designed to recreate that sound. I have that on my pedalboard. I’ve started working with Orange Amplifiers. I’m overwhelmed by their AD30 amplifier, which I have with two 12s. I got my trusty 1966 Fender Vibrolux Reverb. I’m running both in parallel simultaneously. I also use a Heptode phaser, because Paul often used one in the ’70s.

Are there other Little Feat albums that stand out?

My personal favorites are Sailin’ Shoes and their live album Waiting for Columbus. There are numerous gems throughout their records. They had several writers. Bill, Paul and Lowell George are renowned, but Fred Tackett also wrote songs, namely the beautiful “Fool Yourself” and, with Lowell, “Be One Now” on Down on the Farm. Perhaps my favorite Little Feat song is “Long Distance Love,” which I recorded for a video last year.

Perhaps my favorite Little Feat song is “Long Distance Love”

Scott Sharrard

My southern friends call Detroit “North Memphis.” There’s a long history of southern music migrating to the Midwest. My mentors were originally southern – Willie Higgins, Lee Gates and Milwaukee Slim, blues musicians who pushed me toward going deeper down the well where American music comes from.

What is Little Feat’s legacy?

They influenced Led Zeppelin and Bonnie Raitt, for starters. They wouldn’t be the way we know them without Little Feat. Little Feat massively influenced my career.

Who influenced Little Feat?

Lowell’s steeped in New Orleans’ funk influence. Bill’s rooted in that city’s piano tradition. He’d cite Little Richard, Professor Longhair and James Booker. Bill’s songwriting influences range from Dylan and the Beatles to colleagues like Jackson Browne, James Taylor and Allen Toussaint. Little Feat covered many of Allen’s songs.

I see that you feature Payne on Rustbelt. That’s yet another bridge and a perfect segue. In addition to being a paean to the region, is Rustbelt autobiographical?

All my albums are, to some extent. My family is from the Rust Belt going back generations. I was born in Ann Arbor. I spent the ’80s in Dearborn, outside Detroit, under the strain of a crushed urban environment. I then moved to Minnesota, Pennsylvania and, finally, to Wisconsin. My grandparents were union workers with lakefront vacation houses, with paid retirement. Then my parents were left out to pasture fighting the corporate world to survive. There’s another part of being in a crossroads generation.

My mentors were originally southern – Willie Higgins, Lee Gates and Milwaukee Slim, blues musicians who pushed me toward going deeper down the well where American music comes from

Scott Sharrard

The Midwest, however, has a different psychology that’s in my DNA. It’s socially, politically, culturally, gastronomically and artistically mixed-up, chaotic and noisy. That describes my mentality making this record. A great impetus arose while touring with my band from 2017 to 2019 through the Midwest, going over roads I traveled as a kid moving from town to town. It led me to thinking about my kids and the passage of time.

Rustbelt was a three-year work in progress because of Covid. Otherwise, it would have been done last year. We shelved it for 14 months. I entirely recorded it once and re-recorded half of it, all the while rewriting most of the lyrics and music. I’ve never recorded like that. It’s my sixth solo album, and my most personal. It’s a turning point, because for the first time I’m keenly focused on songwriting, which I had looked upon as something you only do with blind inspiration. It’s a craft, like playing a great guitar solo, something you hone and deepen.

I wrote nearly 30 songs and pared it down to nine. It’s a concept album about loss, transition and being a father, husband and musician. I realized they were story songs, touchstones reflecting upon my origins and people I’ve known.

“Gratitude” and “Anne Marie” are particularly introspective.

I wrote “Gratitude,” a secular gospel song, for my wife, Albane. We’ve been through a lot, and she’s a real inspiration. Amy Helm’s on vocals. Anne Marie, my wife’s grandmother, deeply affected my life. We visited her in the south of France. It was like stepping into a Van Gogh painting. She didn’t speak English. We communicated through food and music. Her husband was a Nazi prisoner of war. While writing one night, the song landed in my lap. Justin Schipper’s on pedal steel and Bill Payne’s on piano.

“Michigan Sunset” is the album’s epic song.

Amy and Justin also appear on “Michigan Sunset,” another composition that suddenly came to me. It’s about my namesake, Scott Smith, the lead singer in my dad’s band. Scott was a conscientious objector who was drafted in ’69. On his first tour of duty, he was put on the frontline as a medic and killed immediately.

It was a big responsibility to be named after a gifted person who was stolen. I would imagine Scott’s death when I was a kid. I’ve tried to live up to his ghost. I found my life’s role is to play consistently with my heroes. Scott Smith would be the same age as many of them, maybe would even be one of them. Vietnam was American foreign policy’s original sin. That’s why you must revisit that time.

I found my life’s role is to play consistently with my heroes

Scott Sharrard

I was unsure about this song. I played it for songwriter Gary Nicholson. He said, “It’s your song. Don’t let anybody but you sing it and play it.” That professional nod pushed me over the edge, giving me the guts to try it. “Michigan Sunset” has touchstones to my childhood, things I’d always hear from my family, like, “cold in my blood.” “Michigan Sunset” and “My Only True Friend,” which I wrote for Gregg, are most my important compositions.

Are “Too Many Losers” and “Rising Tide” metaphors for the upheavals the Rust Belt has undergone?

Not necessarily. My favorite line on the record is, “Too many losers are coming up winners.” You can guess whom that’s about. I wrote “Rising Tide” in the winter of 2017, a tumultuous year personally and for the country. For me, it’s prophetic about the unraveling we’ve experienced up through the present and expresses my belief that we’d taken a dangerous turn with a calamity lying in wait.

Duality and contradiction are good fodder for songcraft

Scott Sharrard

The song’s about the wisdom of no escape and challenging the dying of the light. Duality and contradiction are good fodder for songcraft. I’m proud of the outro trade off with Dan Littleton. I’ve never recorded such a long duel. Dan’s among my favorite guitarists. His distinct sound elevates the music. I discovered him playing with Amy. He’s outstanding on her Didn’t It Rain album.

How does the instrumental title track fit into the album’s structure?

Two versions play throughout like an actual record, front to back. It’s an old-school approach linking some of the different tunes creating an instrumental journey from the Midwest to NYC. The first version in the album order features Justin’s unique use of effects with the pedal steel. He also adds some baritone guitar.

It’s the album’s sonic palate cleanser. It ends with keyboard wizard Brian Charette’s Rhodes solo. “Rustbelt Reprise” reinterprets the initial version and continues the guitar tradeoff between Dan Littleton and me from “Rising Tide.” Dan has an unconventional approach to melody and tone in his lead playing.

Your blues vocals pack a wallop.

I caught a bit of Gregg on the way out. I was alongside him for a decade. I’ve tried to incorporate whatever I can from him. I’ve other influences such as Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and Johnny Adams but I don’t aim to sound like anyone.

Rustbelt has many impressive backing vocals, notably on “Only Human.”

The crème de la crème, Catherine Russell, is on that, with Charlie Drayton on drums. She’s almost her own gospel choir. Catherine also sings choruses on “Michigan Sunset.” Our singers are an embarrassment of riches, such as Dan Littleton’s wife, Elizabeth Mitchell. They’re associated with Amy and the team at Levon Helm Studios. The secret weapon, vocally, is Adam Minkoff, who plays the shit out of a bass. Adam and Catherine are together on “On the Run Again.”

“On the Run Again” contains vivid imagery, such as “Hope is like a candle that you try your best to hold.”

Some imagery seems literal, but it’s not. A favorite lyric is, “I left you on the beach with a diamond in your hand.” The ring isn’t on her finger; did she say yes or no? I decided to leave it ambiguous. I’ve never written songs with so many long verses, something I associate with my favorite writers Warren Zevon, Dylan, Elvis Costello and Waits, and, from an earlier time, Cole Porter. I’m happy with the lyrical arc. It’s my signature song describing a dedicated musician’s life.

“Bad New” exudes conflict and danger, especially with its abrupt ending.

That’s also a song about being a musician and being a man. It’s Jekyll and Hyde in reverse. It’s a live-show staple sometimes lasting 12 minutes. “Bad News” and “On the Run Again,” Rustbelt’s opening songs, are companions, musically and lyrically.

When we approached the conclusion, drummer Eric Kalb asked, “How do we end it?” We had often played it live, never ending the song that way. We made Rustbelt in two recording studios. One closed due to Covid, the other underwent major renovation. For a while, we couldn’t get the studio.

The rhythm section recorded “Bad News” live. I overdubbed the solo in my apartment in one take with a plug-in, without amplifiers. It’s an old Fano SP6 built by guitarist [and luthier] Dennis Fano, with a Lollar P-90 in the neck, the only pickup I use on solos.

I used an Origins Effects RevivalDrive for the overdrive and a Strymon Flint for the spring reverb. I had a Scuffham Amp plug-in set up to be like a Dumble, and I used a Tweed Deluxe. You can move around the virtual mics. My producer Charlie Martinez and I were happy with the tone.

Do your covers on Rustbelt spotlight any of your personal icons?

I chose “I Ain’t Gonna Worry” by Mississippi’s Tommy Tate to arouse interest in his incredible blues singing and songwriting. Check out his Koko Sessions. He died in 2017. I know Dr. John’s “A Losing Battle” from another mentor, guitarist/songwriter Stokes from Milwaukee. We regularly played it together. Since he died in between my albums, I dedicated it to him, recording it alone with two microphones and a laptop. It’s my finale, since it doesn’t get more Rust Belt than Stokes.

What other guitars and gear do you use?

Throughout I used my Heritage, Fano and Stratocasters, one with a Stratoblaster, with a loud bridge pickup for slide work. On one or two songs, I use a BNG guitar from Israel. They make a beautiful hollowbody guitar with P-90s.

Acoustics-wise, I use my 1964 Martin 000-18. My dad passed it down to me. I use a Farida for Nashville tuning, where you put all the thin strings from a 12-string and don’t use the thick strings, making a six-string sounds like a mandolin. I combine that with my Mule Resonator guitar on several songs.

My Heritage and Farida are from Kalamazoo, Michigan and my Mule Resonator is from Saginaw, Michigan. How Rust Belt can you get?

Scott Sharrard

On “Michigan Sunset” and “Anne Marie,” the main guitar characters are a Mule Resonator, a Nashville-tuned strumming guitar and a regular strumming guitar, usually my Gibson Dove. My Heritage and Farida are from Kalamazoo, Michigan and my Mule Resonator is from Saginaw, Michigan. How Rust Belt can you get?

Is Rustbelt a watershed for you?

With past recordings, I felt I was coming on fast and going to knock it out. Now I don’t care what anybody has to say or thinks about it. I did this one for me. This was a bloodletting.

Buy Rustbelt by Scott Sharrard here.