“We’re going to do this because Bob Dylan asked me to.” John Fogerty says one word from the folk icon convinced him to do something he’d avoided for 15 years

Bad feelings about his Creedence Clearwater Revival days made him swear off his old hits. Dylan changed everything in a moment

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

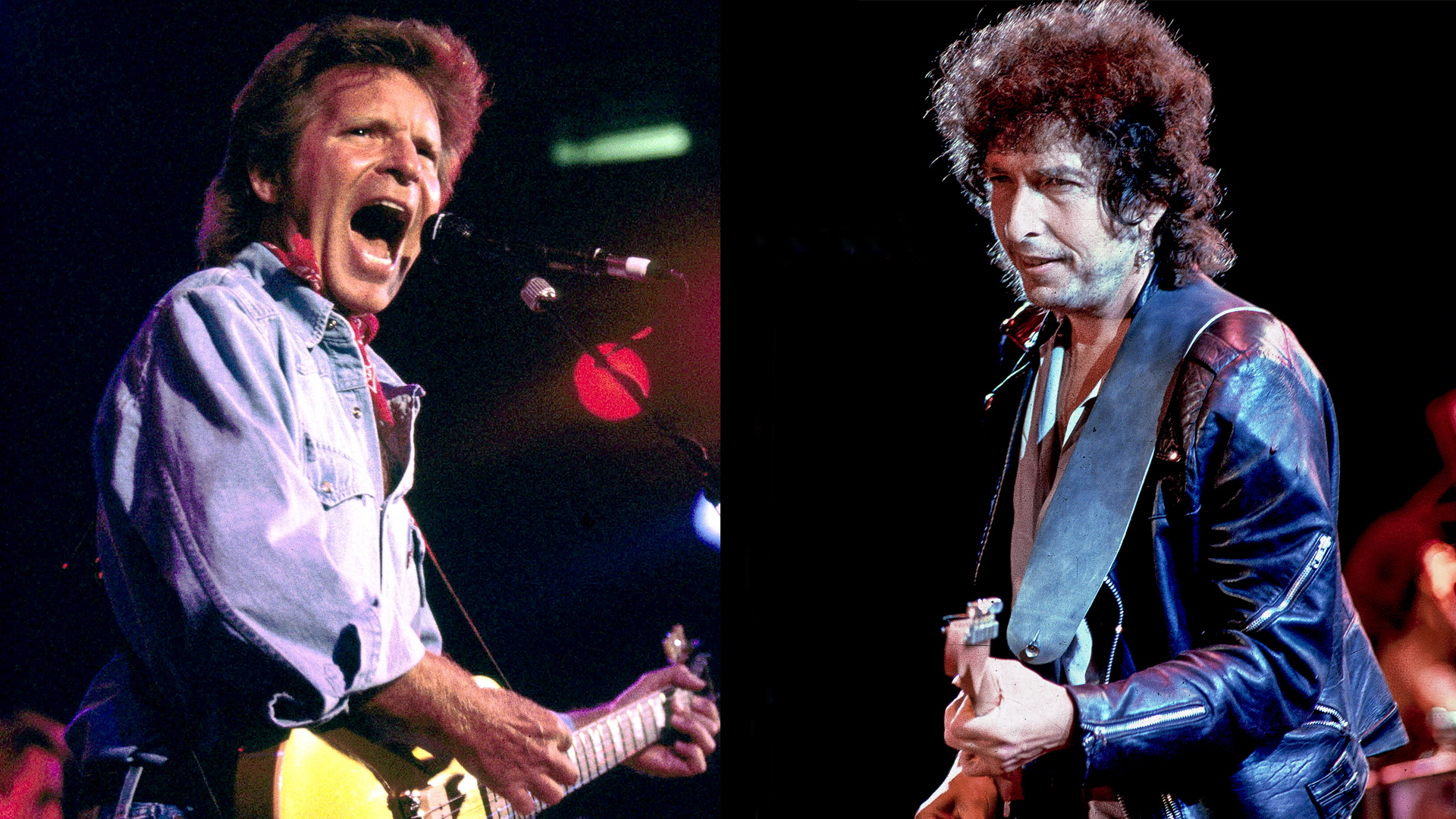

For 15 years, John Fogerty refused to play the hits and timeless tunes he wrote and recorded with Creedence Clearwater Revival. Driven by bitterness over the exploitative contracts he had signed and the legal battles with his former label boss, Saul Zaentz, Fogerty turned his back on CCR classics like “Bad Moon Rising,” “Fortunate Son” and "Proud Mary.” He felt that if he performed them, the enemy would profit, and that was simply intolerable.

His long, self-imposed ban finally ended spontaneously one night in Hollywood — with a little help from Bob Dylan.

The year was 1987 and the location was North Hollywood’s Palomino Club, a revered venue known for its country-rock heritage. Onstage, the acoustic blues legend Taj Mahal was playing an electric set. In the audience, three rock icons were watching him play: George Harrison, Bob Dylan and Fogerty.

“I’d gone there to see Taj Mahal, who I love, and sat down,” Fogerty recalled in a video newly posted to TikTok. “And at some point I heard a rumor that George Harrison was there, that he was in this cloak room. So I went in and talked to George for a little bit.

“Then I heard a rumor that Bob Dylan was somewhere in the room. I didn’t know until later that George and Bob were great friends — they were really tight — and they had arrived together.”

Mahal was aware of the famous guests in attendance, and soon, Fogerty recalls, Harrison and Dylan had joined the performer onstage.

“I’m usually kinda shy, but for some reason [I thought], Man, I hope they have another guitar!” he said with a laugh, recalling the event. “Please call me up there!”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Soon enough, Mahal told Fogerty to come up and join them.

At some point the crowd started calling out for the musicians to play their own tunes. Dylan led the group through “Watching the River Flow,” and Fogerty recalled Harrison playing “Honey Don’t,” a Carl Perkins hit the Beatles recorded in 1964.

“And then the crowd starts, ‘John, John! C’mon! Play ‘Proud Mary’!” he recalls. “And this was during the time that I had sworn off playing my own songs from the Creedence Days because of legal and emotional entanglements.”

Fogerty admits he was feeling “stubborn.” He had avoided this moment for half his career. He wouldn't do it.

But then, standing to his left, the famously reclusive Bob Dylan — a man who himself had often wrestled with audience demands to perform his classic tunes — leaned over to Fogerty.

“He turns to me and he goes, ‘John, if you don’t play ‘Proud Mary,’ everybody’s gonna think it’s a Tina Turner song.’”

The air went out of Fogerty's stubborn resistance. He realized Dylan was absolutely right.

“Proud Mary” had been CCR’s first big hit, a tune Fogerty had written in the throes of an almost mystical inspiration.

I had sworn off playing my own songs from the Creedence Days because of legal and emotional entanglements.”

— John Fogerty

“I realized I had just written what you’d call a classic,” he told Guitar Player in 2024, reflecting on the song. “I was awestruck. I was excited, trembling. I was almost scared of it. It was almost as if you’d walked into a room and discovered some amazing treasure and secret. And at that first moment, I was terrified that this might be it, that I would never get to do this again.”

CCR took the tune to number two on the singles chart, the group’s first significant showing there. It was one of the many hits Fogerty composed and released with CCR — and performed with his Fireglo Rickenbacker 325 semi-hollow electric guitar — in 1969.

But it was Ike and Tina Turner’s 1971 rendition of the song that brought it to an entirely new level. Although it didn’t reach the chart heights of CCR’s version (number four was the best it could do), their take on “Proud Mary” was explosive and quickly became a show-stopping number in their concerts.

Turner had made the song her own by opening it with one verse performed at a slow, bluesy pace before launching into a fast funk that got every member of the audience out of their seat. Tina and her trio of background singers, the Ikettes, shimmied in their sparkling mini dresses, while Tina, gyrating furiously, held the spotlight.

By the late 1980s, Turner was a solo artist at the peak of her game, with monster hits and sell-out shows where “Proud Mary” remained a centerpiece. Fogerty was enjoying a resurgence of his own with his hit album Centerfield.

But Dylan’s logic was — as Fogerty would later admit — “irrefutable.” No one was talking about the original “Proud Mary.” Tina Turner owned it now.

Stunned by Dylan’s argument, Fogerty finally gave in. He looked out at the cheering audience, looked back at his fellow legends onstage, and with a laugh and a profound sense of release, introduced the song with a grin.

“We’re going to do this because Bob Dylan asked me to,” he stammered. “Holy mackerel!”

“Proud Mary" erupted from the stage, performed by its author for the first time in 15 years. It was a joyous, cathartic moment, and according to Fogerty, he had a “great time” playing his own work again.

While Fogerty didn't immediately embrace his CCR catalog, this impromptu jam session — spurred by Dylan’s insightful comment — was the moment the dam broke. Afterward, Fogerty began the long process of reclaiming his musical legacy for himself and his fans.

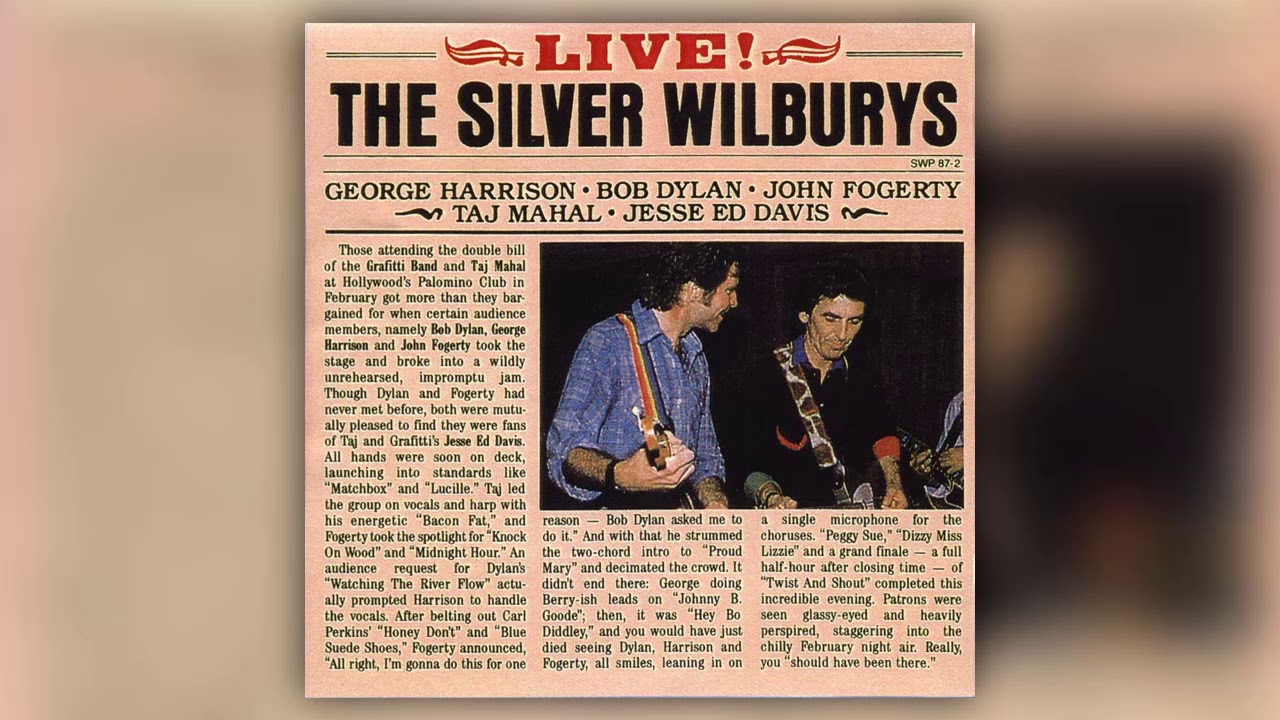

The event would go down in history for another reason. Soon after, Harrison and Dylan formed the Traveling Wilburys with Tom Petty, Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne. The Palomino quartet became known as the Silver Wilburys, a nod to the Silver Beatles, the embryonic precursor to the Beatles that featured Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Stuart Sutcliffe.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.