“People like Yngwie Malmsteen should be forgotten as soon as possible. It’s got very little to do with music...” A classic and very frank interview with Johnny Marr

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

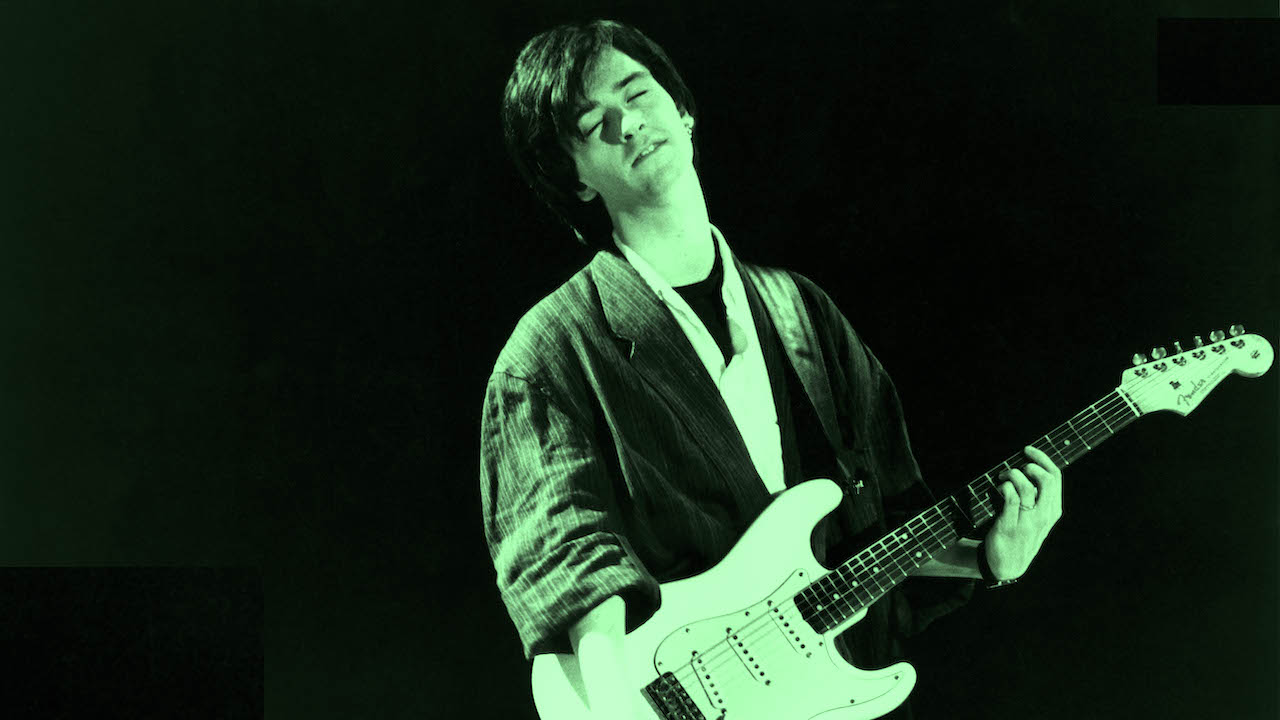

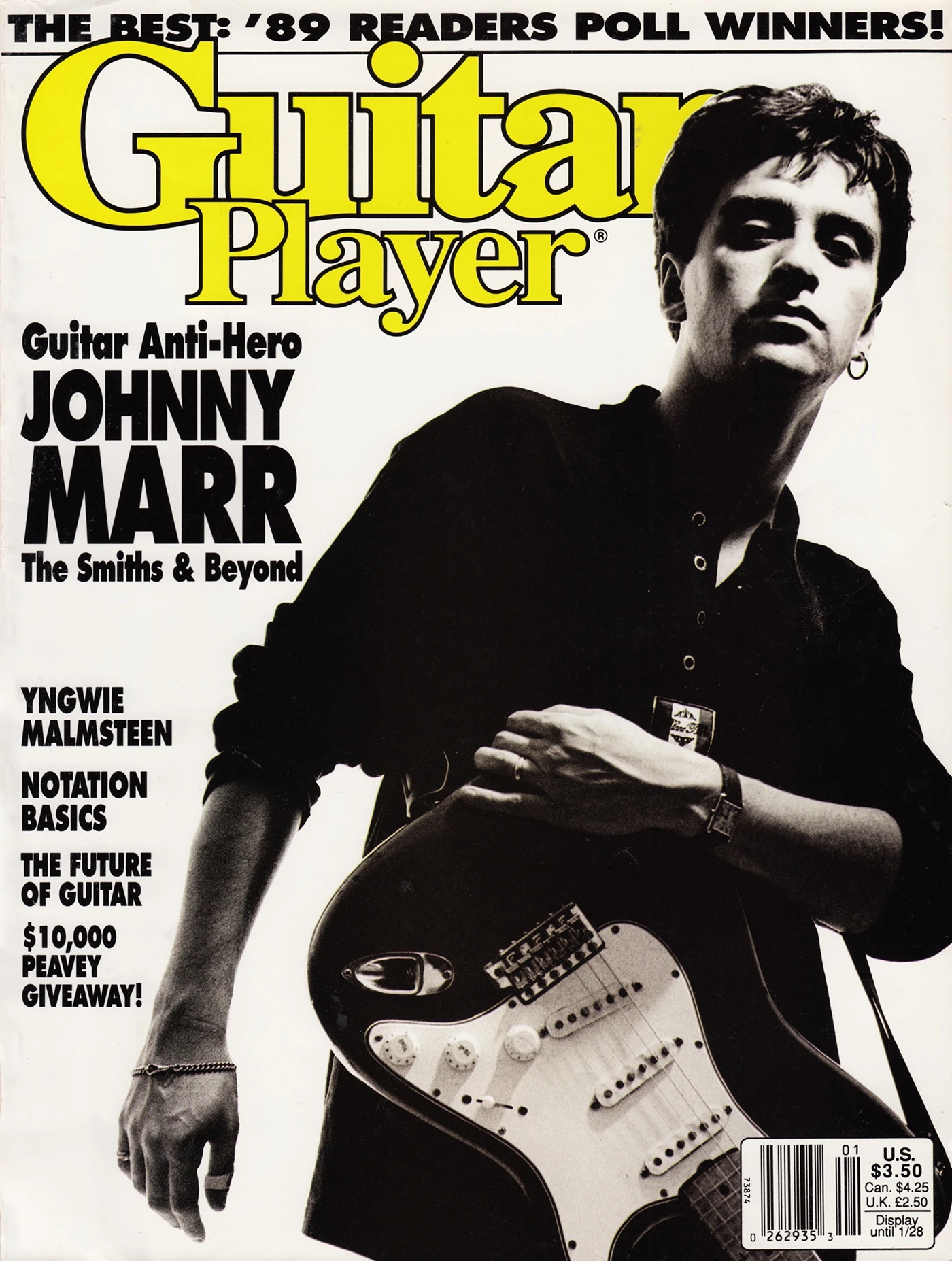

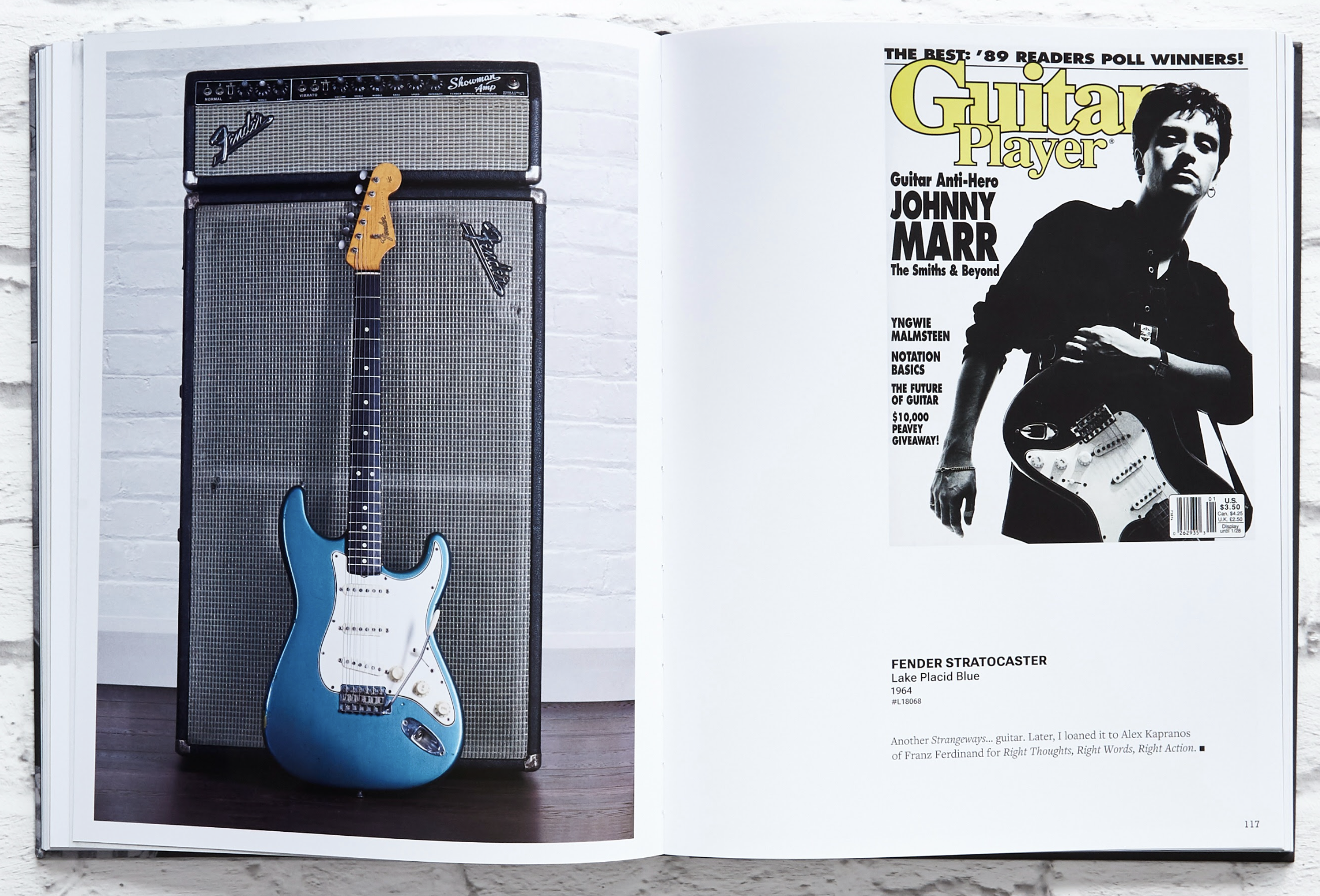

Back in January 1990, Guitar Player opened the new decade with a new type of guitar hero on the cover. In fact, said writer and Guitar Player Editor Joe Gore, Johnny Marr had done everything he could to avoid becoming a guitar hero: he avoided guitar solos whenever possible, put songs before showmanship, was subtle in his innovations (not for him posing with a four-necked guitar), violated pop music conventions whenever possible and denounced guitar heroism loudly and frequently.

At the time of this interview, Marr was 25 years old with more than a dozen successful albums to his credit. Marr was the musical director of The Smiths, the most critically acclaimed English band of the 80s. In England, the quartet generated controversy, 17 hit singles, and an endless parade of imitators. In the U.S. the band became a college/underground radio staple and developed a fanatical cult following (a Spin magazine readers poll named the band's The Queen Is Dead the Best Album Of All Time, edging out Sgt. Pepper).

The Smiths' records juxtaposed Marr's vibrant, tuneful pop arrangements with Morrissey's mournful, love-it-or-hate-it voice and witty, politically charged lyrics. Morrissey and Marr wore their record collections on their sleeves, and their influences – Motown, early Stones, and American punk prominent among them – were readily apparent. At the same time, they attacked the sexist, escapist conventions of pop music.

Despite their traditionalist streak, the Smiths developed an utterly original group sound, based largely on Marr's elaborate tapestries of overdubbed guitars. His oddball chord sequences and jarring major/minor clashes were leavened by a Beatles-esque sense of melody and an Olympic-sized palette of guitar tones. Marr's playing embraced the rock primitivism of the 60s, the funky groove of the 70s, and the bright, open-string chimey-ness of the 80s. He may have played a Rickenbacker, but there wasn't a Byrd in sight – it was a whole new angle on jingle-jangle.

In August ‘87, Marr resigned, citing musical and personal reasons and went on to play with Talking Heads, the Pretenders, Bryan Ferry, Paul McCartney, and became a full-time member of The The. Credits since then include Electronic, his band with New Order’s Bernard Sumner, Modest Mouse, The Cribs, Billy Bragg, the Pet Shop Boys, Kirsty MacColl, Beck, Oasis, Pearl Jam and many more.

No matter what the project, Marr's guitars support the song, not a bloated shred-head ego. Too many "guitar heroes" bludgeon you with flash, but leave you hungry for music. On a Johnny Marr record, the song speaks first, while repeated listenings reveal the richness of the accompaniment.

This month he released a book, Marr's Guitars that chronicles his obsession with guitars and guitar playing. "Guitars have been the obsession of my life," says Marr, "They’ve been a mission and sometimes a lifeline." Back in 1990, he personified a new breed of guitar player…

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You're not afraid to play simply, if it suits the song.

I've always believed that any instrumentalist is basically just an accompanist to the singer and the words. That's born out of being a fan of records before I was a fan of guitar players. I'm interested in melody, lyrics, and the overall song. I don't like to waste notes, not even one. Who was it that said, "The reason why all those guitar players play so many notes is because they can't find the right one"? I like to put the right note in the right place, and my influences have always been those kinds of players. Keith Richards comes to mind, and I really Like Nils Lofgren's soloing, because he's so melodic. I love John Lennon's rhythm playing, and George Harrison was an incredible guitarist.

There's a lot of guitar culture that I don't like at all. I find the traditional idea of the guitar hero to be really irrelevant to the 1990s. I don't think that young people are that impressed with some guy brandishing Spandex trousers and a hideously shaped guitar, playing that kind of masturbatory, egotistical noise. Being a soloist who wants to just display virtuosity is a dated philosophy, and I don't think there's any room for it in pop music. It's the last stand of late-60s/early-70s rockism, and it should have gone a long time ago.

Judging by the letters we receive, much of our readership is still obsessed with the mythology of the guitar hero.

I get Guitar Player, Guitar World and Guitarist every month, but I just read the equipment and LP reviews. I find most of the interviews absurd, and so anally retentive that they're meaningless. I don't know about America, but here [in the UK], no one has any respect for someone who can play a million notes per minute but can't put together a decent tune that someone can sing to or feel some sort of emotion from. I have a healthy respect for guitarists like Joe Satriani and Eddie Van Halen, disciplined players who really know what they're doing – if you're going to be a virtuoso, you can't be hit-and-miss. But I think people like Yngwie Malmsteen should be forgotten as soon as possible, I really do.

It's got very little to do with music, and the "I'm the fastest gun in town" idea is almost like homosexual panic. Nothing against gays, but when players perpetrate this incredibly sexist image of being so macho, I find it suspicious. Plus, I can't do all that stuff, so that's why I say it's stupid [laughs].

You've often sung the praises of the three-minute pop song, but [The The’s] Mind Bomb features longer songs with expansive arrangements that take some time to unfold.

On Mind Bomb, I was getting more into atmospherics and noises, but melodic noises, not just aimless doodling. And I wanted to get into open, wide arrangements with fewer chord changes.

You've said that one should be able to visualize a song with only a voice and an acoustic guitar. But that hardly applies to an atmospheric soundscape like The The's Good Morning, Beautiful.

True, but I still think that's a good guideline for a writer to follow. Before attempting any track, I have the overall picture in my head. Even if it doesn't work on an acoustic guitar, at least I could sing all the parts into a Walkman. It's nice to have accidents as a guitar player, but as a writer, I like to know exactly what I'm doing.

But my philosophy has changed slightly. I've been making records for eight years, and I wouldn't like to anchor myself down to an attitude I had when I was nineteen.

How accurate are your visualizations of the finished song? Is it trial and error?

To be honest, the parts that I think will work almost always do. But in the process of gluing one part over another, new parts spring to life. So there is a fair amount of trial and error. I'm into experimentation, but that only feels good once you know you've got a really good song cooking. I don't believe in doodling around, waiting for inspiration to drop through the ceiling.

If I'm not hearing anything, I'll go for a walk for 15 minutes. Actually, I come up with my best melodies away from the guitar, like when I'm in a taxi, or making tea in the studio, hearing the track from down the corridor. The ones I sing before I play them are always my favorites.

You're experimenting more with processed sounds.

The Smiths were quite a purist group, and I was a great believer in traditionalism. Just plugging a Gibson ES-335 into my trusty Fender Bassman or Twin Reverb was romantic. But now I understand that when technology is used by someone with taste, you can have tasteful results.

Whatever makes for a more interesting end result, I'lI use. For example, I've been using the Roland GR-50 guitar synth, and I'm really impressed with that. If technology allows you to come up with an absolute killer part, then it can only be a good thing.

Is there any guitar synth on Mind Bomb?

No, but I find it really inventive, especially if I'm just writing in a hotel on a four-track. I sometimes use the Casio MIDI guitar for that – the onboard sounds are cheesy, but they're good for demo purposes. It's corny to say, but if Hendrix had been around, he would have exploited today's technology for all it was worth, as he did when he was alive, as did The Beatles. Just because they used 8-track in their time doesn't mean that that's what you use nowadays if you want to be as good as The Beatles. But I've still got a healthy respect for traditional guitar playing and a traditional guitar setup.

You're also incorporating more bizarre, unpitched ideas in your playing.

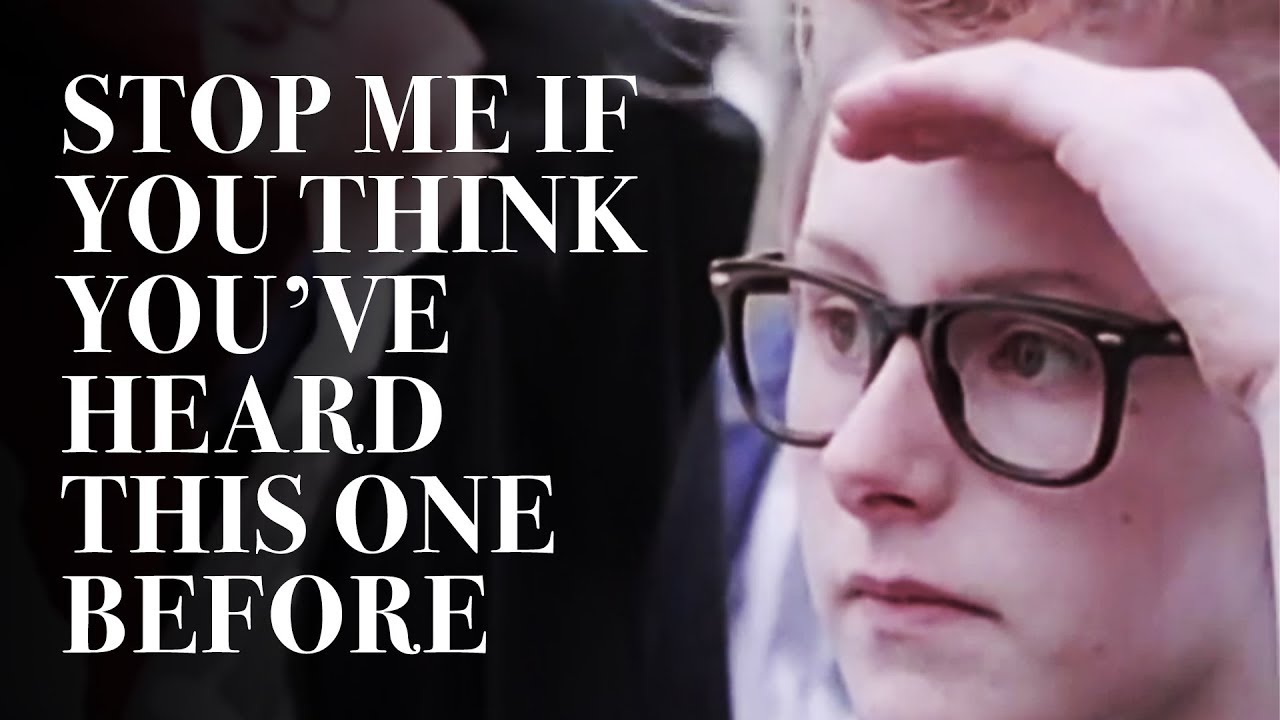

I'm trying to be open to any ideas, so long as they're fairly melodic and they relate to what the singer is singing. I'll try any trick. With The Smiths, I'd take this really loud Telecaster of mine, lay it on top of a Fender Twin Reverb with the vibrato on, and tune it to an open chord. Then I'd drop a knife with a metal handle on it, hitting random strings. I used that on Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before [from Strangeways, Here We Come] for the big "doi-ngs" at the start. And I used it on This Charming Man [from The Smiths], buried beneath about 15 tracks of guitar.

Those dense, overdubbed textures are one of your specialties.

Once I've put a track down, I put on a pair of cans and listen to the track really, really loud. I listen for the things between chord changes, the things that you almost play accidentally moving from one chord to another, and I try to fill in those gaps. I try to glue together those harmonic and melodic overtones, and state the things that you imagine you're hearing. And if there's a sad melody there, I'll find it, even if it's in a major key. I really like melancholic melodies.

Yeah, even though most Smiths tunes are in major keys, the vocal and instrumental melodies often emphasize the interval between 3 and 5, the minor 3rd within the major chord. It's like a sigh.

That's right. And moving up in semitones is really good, too. I've never liked jolly music full-stop, unless it's someone like the Fatback Band.

Even when you were playing a lot of chimey, open-string chords on a Rickenbacker, your playing had a melancholy feel. You avoided all the jingle-jangle cliches.

Well, I've been open to tons and tons of influences. My parents are avid country music fans, and I got into music at an early age. My father played accordion, and he taught me harmonica. Because we were an Irish family, we had parties all the time. I had an uncle who played guitar and sang hits of the day, like Walk Right Back by the Everly Brothers, and I thought that was really cool.

By the time I was 10 or 11, I started to buy T-Rex records they were the first group I thought of as "mine." Jeepster was the first record I bought. The main riff, which was a complete steal from Howlin' Wolf, got me into playing guitar. At 13 or 14, | started playing more seriously, and I backtracked into Motown. I'd work out the chords, but I'd try to cover the strings, piano, and everything with my right hand, trying to play the whole record on six strings. That's one reason why I'm so chordally-oriented, and why key changes and the strategy of arrangement are really important to me. I was heavily into Smokey Robinson and [Motown songwriters] Holland/Dozier/Holland, because there was only Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple around.

Then I moved from the poor side of Manchester to the most notorious part of the Southside, Wythenshawe, which was full of musicians. It was normal for someone to have a guitar there – on the poor side, if you wanted one, you had to steal it. Billy Duffy, who now plays with The Cult, taught me a few chords, and someone else turned me on to Pentangle and Fairport Convention with Richard Thompson. I started to get into guitar players as such, and when I got into Nils Lofgren, there was no turning back. He had a lot of cool and a lot of flash, but he had respect for the song and melody. Plus he's one of the best white singers l've heard – I could talk about him for years. It was because of him that I started playing with a thumbpick. And I got into the one-note solo from Neil Young's Cinnamon Girl, which I thought was incredible.

Then when I was 13 or 14 – hey, presto! – all the kids at school were getting into punk rock. I was starting to develop a healthy interest in songwriting and good melodies, and then this movement came along. I knew it was pretty cool, but I was too young to appreciate it, because I couldn't get into the clubs and spit on the groups. I was caught between two things.

So you were saddled with some unfashionable influences.

That's exactly what happened. But I had my own thing, and that held me in good stead in the future. It was not very cool to be into the Supremes when you're supposed to be into The Jam. But I did get into the American new wave scene, Patti Smith in particular. When I heard Horses, that changed me quite a lot. Then I got into Television's Marquee Moon and Talking Heads '77. After Patti Smith, I thought, "Great, I can play big, loud chords on a Les Paul through a Fender Twin Reverb, instead of sitting around with an acoustic guitar." I could pick like Bert Jansch, but I wanted to look like Ivan Kraal from the Patti Smith Group. From then on, I didn't look back.

Unlike some darker-sounding post-punk bands, The Smiths stuff had very pretty surfaces, with lots of major 7th and 6th chords.

Reel Around The Fountain was my interpretation of James Taylor's version of Handy Man. I was trying to do a classic melodic pop tune, and it had the worst kind of surface prettiness to it. But at the same time, Joy Division was influencing everybody in England.

That dark element- it wasn't that I wanted to be like them, but they brought out something in the darkness of the overall track. In a sense, Bernard Sumner [of Joy Division, later to become New Order] was one the most influential guitarists and writers of the 80s. There would never have been a U2 or a Cure if it hadn't been for Joy Division.

So where does the jingle-jangle come from?

The Byrds is an obvious answer, and I did like them, but not as much as people make out.

I don't hear a lot of Roger McGuinn in your playing. You never use those open-position add9th-sus4 voicings.

That's good, for a change. Actually, a lot of it comes from Neil Young and Danny Whitten of Crazy Horse, but as if they were in a pop group. And it was George Harrison who influenced me to get a Rickenbacker. Ticket To Ride – what a brilliant song! But most of all, the jingle-jangle came from James Honeyman-Scott of the Pretenders. He was the last important influence on my playing before I went out on my own. The first time I played Kid with the Pretenders, I couldn't believe it. I've used that solo to warm up with every day for years.

Unlike a lot of other jingle-janglers, you didn't rub the listener's nose in your guitars. There's was a lot of depth and mystery to your textures.

Again, that comes from being influenced by groups and records, and not guitar players. For example, [producer] Phil Spector was really important to me, and I like the idea of records, even those with plenty of space, that sound "symphonic." I like the idea of all the players merging into one atmosphere. I tend to hear the record as it will be produced as I'm writing the song, and I hear how the guitars will link together. The Rolling Stones were a big influence in the way the two guitars played off each other.

And Roxy Music was very important to The Smiths. They always had fantastic intros and outros, and on the eleventh hearing you'd pick out something you'd never heard before. But I must give credit to John Porter, who produced a lot of The Smiths' records. He worked with Roxy Music in the 70s, and he taught me a hell of a lot about guitars. He figured that if everyone spends two days getting drum sounds, why not spend the time on the guitar sounds if you're a guitar group? We spent a lot of time on our sounds, and I still do.

You often tune your entire guitar up a whole step, to F#. Why did you start doing that?

When Morrissey and I started writing, my ideas just sounded too low when we started working on them with the voice. But [Smiths bassist] Andy Rourke didn't play in F#, so all the guitar parts sounded really toppy on the first album, while the vocals were in a low register. It made for an odd sound that really worked. I also use a lot of regular boring open tunings like G, D, and A, and I use Nashville tuning all the time. I've got an Epiphone Coronet with one pickup, and I string it with the high stings from a 12-string set.

It's a really zingy, trebly guitar. I used that on a lot of things that people think are 12-string, like the end of The Headmaster Ritual. I also used it on the studio version of The Draize Train [the B-side of the Panic single], along with two Rickenbackers. I was working with Alan Rogan, the famed English guitar technician. He said, "Well, if you want a Pete Townshend sound, I'II bring down two of Pete's guitars." I don't know whether Pete knows about that!

Did you use thumbpicks with The Smiths?

I played with a flatpick because I thought we needed a Ramones element. But since then, I've gone back to the thumbpick. I wanted something more fluid, and when you have all five right-hand fingers going, your fingers go to progressions you don't even know you're doing. I don't use right-hand nails – I'm a horrible nail-biter. But my fingertips are really hard.

Do you have trouble getting a light strum feel with the heavy plastic of the thumbpick?

I find that's one of the most difficult things. But I try to zing it with my fingers, like an upward flamenco-style stroke. I often hold the thumbpick just like a regular pick, just to get that bright attack. My thumb's quite fast. I use fingers and thumbs for soloing, coming up with parts, or for funky things where l'm sort of slapping. That's what I do on the funky line in Violence Of Truth [on Mind Bomb].

Which records captured the Smiths at their peak?

The Queen Is Dead is certainly the best LP we made, the most focused from start to finish. It was a dark point in my life, but creatively, it made for something really brilliant. I try to take care of myself and live in the real world, but some of my best work has been produced when I wasn't in the real world. Pop music isn't worth killing yourself for, but when you do something extra special, it's almost worth it. Singles-wise, my favorite is How Soon Is Now.

Were you behind The Smiths' eventual move towards more orchestrated, "produced" sounds? Your approach was quite like The Beatles at times.

Musically, the production was my responsibility. But to be fair, it was a 50/50 thing between Morrissey and me. We were completely in sync about which way we should go for each record. But we started to lose that near the end of the last LP, which was another signal to me that we should stop. The White Album [The Beatles] was the strongest influence on us towards the end, things like Cry Baby Cry and I'm So Tired.

Were The Smiths misrepresented to American listeners, who knew the band through their albums rather than their singles?

I'd say so, because singles were one of the most important things that brought us together, a love of the classic 7" pop format. Those were the records I grew up with. A huge facet of what we were about was missed out on, because singles culture is so ineffectual in America. But I thought Louder Than Bombs, the singles compilation, was great.

What did you think of the live album, Rank?

Guitar-wise, I'm not particularly proud of it, partly because I used to be in such panic before I played onstage that I either froze up, or I got so drunk that I was sloppy. That was a combination of natural stage fright and being in the ridiculous position in England of being so scrutinized. I never played as well on tour.

Did you see budding alcoholism as a warning sign about your career with the band?

Yeah, I did, and to be honest, it was more than "budding." I find the "guitar player does tour, is driven to drink" idea very corny, but it could have been a lot worse. It sounds incredibly Guns N' Roses, but The Smiths went through every conceivable rock and roll tragedy: drug busts, police harassment, controversy. We had everything but a death, thank God. That was avoided by us splitting up.

You were luckier than some.

We were smarter than some. Some groups actually start believing they're the Rolling Stones, and that's how they do themselves in.

What prompted the final split?

It was mostly a personal thing. We were working at such a breakneck pace – 50-odd tracks in four years – that I thought I was going to end up repeating myself.

Also, I was frustrated with what people expected me to come up with. By creating your own rules the influences, methods of songwriting, and so on that you allow yourself to use, you end up boxing yourself into a corner of musical politics. And if you step out of that corner, it's immediately called "sell-out." Some "fans" – for want of a better word – just wanted me to jingle-jangle on my Rickenbacker till I died. But if I have to forsake fame, fortune, and popularity for the experience of being able to play exactly what I want when I want, I'd do it again.

But in the beginning, it was good to be in a group that stood for and against certain things. We were against synthesizers, the Conservative government, groups with names like Orchestral Manoeuvers In The Dark, the English monarchy, cock-rock guitar solos, and the American music scene at the time. We stood for the Englishness of the Kinks, T-Rex, and Roxy Music, the arty quirks that kept those groups from being huge in the U.S.

We were into the Rolling Stones, the MC5, the Patti Smith Group, Oscar Wilde, [play-wright] Shelagh Delaney, and certain actors. Some things were really important to us, and we made no secret of our obsessions. Morrissey and I wanted to be a modern-day Leiber and Stoller, writing bubblegum backing tracks with intense lyrics. We weren't minimalistic, but we wanted to sound very home-grown, not like a polished major-label group. I'm very proud of everything we did, musically, lyrically, and politically. It was a really great time, but only a fool doesn't know when it's time to stop.

Were you widely scouted when the news of the breakup hit the street?

Lots, and I was quite flattered. But I was so lacking in confidence when I left The Smiths that I was afraid. To be honest, I thought I'd flushed my career down the toilet, but I was gonna have a good time, anyway. But it worked out well. I'm quite happy to keep on turning things down, because the people I'm involved with – The The, Kirsty MacColl and Bernard [Sumner] – are my favorites. I'm very proud of the Kirsty MacColl record. I wrote two of the songs and played on nine tracks. I got a chance to play opposite Robbie Mcintosh and Dave Gilmour.

Why did you feel you weren't the right guitarist for The Pretenders?

It was mainly a question of timing. Chrissie wanted to take a break to write the LP she's working on now, and I was fired up to tour or make a record. The tracks I cut with The Pretenders I regard as a complete success. They were first take, with live vocals and no punch-ins or re-recording. Chrissie is so good that she can inspire a group with her personality and her voice to play the best they've ever played – she's that good as a front person.

I feel very good to have played with Chrissie, but the most important thing was our personal relationship. She helped me through a lot of crap with The Smiths' split, and I'm forever indebted to her.

Did you consciously put aside the Rickenbacker after the Smiths era?

Yeah, I was getting a little tired of the things I was coming up with on it. About '86, I got really into the Les Paul and rediscovered Peter Green. I tried to play less chordally, a little more solo-notey. But the solo on Paint A Vulgar Picture [Strangeways] was done on a Strat.

How did it feel to play a regular single-note solo like that after becoming known as the man who never soloed?

I was really pleased that the first solo as such on a Smiths record was one you could sing. Since then, I've done more wild, wacky fast things; that's going to be more of a feature of my new stuff. I like improvisation in the right place, but I find most solos corny. That "now I'm gonna solo my ass off" attitude is the equivalent of someone just being a loudmouth and talking rubbish. I prefer the idea of a relentless riff that goes around and around, like the line on The Violence Of Truth [Mind Bomb].

So what would you call the non-solo guitar passages on tunes like The Queen Is Dead or Shoplifters Of The World Unite? They deliver the charge you'd expect from a solo, but you don't actually solo.

I think of them as guitar breaks. I like the one in Shoplifters – that was the first time I used harmonized layering. People have said it sounds like Brian May, but I was thinking of stacked Roy Buchanans. For the frenzied wah-wah section on The Queen Is Dead, I was thinking 60s Detroit, like the MC5 and the Stooges.

Nowadays, you seem to be using more dry, un-jangly, funk-type riffs than you did with the Smiths.

I like those overstated guitar parts, like the one on the Fatback Band's Yum, Yum, Gimme Some, which gives you all the rhythmic bits that your body wants to feel. A classic for me is Nile Rodgers' guitar part on Chic's I Want Your Love. All that is born out of an early love for Bo Diddley. That beat is the root of all dance music. When I do sessions and I can't find a way into the track, I look for the Bo Diddley, whether it's half-time or double-time.

That figure runs through all African-derived music.

That's right, and if it doesn't run through it specifically, it does subliminally. Bo Diddley took the bits that you wanted, and hooked them all together in an overstated way. One of the things that attracted me to Bo Diddley early on was my parents' copy of Elvis Presley's Marie's The Name, which has that beat. The Talking Heads called me in specifically because the song Ruby Dear had a Bo Diddley groove – that's incredibly flattering.

You often create odd clashes by superimposing the major and minor modes.

I find a blue note whenever I can. I try to find the poignancy in any kind of lick. Not to get too poetic here, but I find a distinct lack of poignancy in most guitar playing I hear. It's as if people feel that by virtue of being a guitar player, they have to have this swashbuckling, gung-ho approach to music, an overblown, vulgar approach. I'd prefer a few notes played in the right place on one string. For example, I liked the melody at the end of Stop Me If You've Heard This One Before, but it just felt a little too accomplished. I wanted it to sound like a punk player who couldn't play, so I fingered it on one string, right up and down the neck. I could have played it with harmonics or my teeth, or something clever, but the poignancy would have gone out of the melody.

You haven't had any formal theoretical training, yet your harmonic ideas are quite sophisticated.

The older I get, the more I realize that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. I try to avoid an overly theoretical approach at all costs. I like putting in parts that I don't understand, parts that just sound good by ear. On the Talking Heads' Cool Water [Naked], for example, I tuned a Gibson ES-335 12-string to an atonal drone against the track at David Byrne's encouragement. I didn't know what the tuning was, so I was playing all kinds of shapes that I never would have gotten into. We miked it acoustically, without an amp.

I try to avoid thinking about scales, keys, and anything like that. I really like the idea of not knowing what I'm doing. Ultimately, I end up with something more original, a little more from the heart than the head. I know it doesn't work for everyone, but it's convenient for me because I'm quite a lazy person [laughs]. But that's one of the things I'm looking forward to about getting old and grey – I'm going to learn what I'm actually doing. But I think it would be the kiss of death to my songwriting if I did that right now.

At times, your style is reminiscent of African highlife guitar – playing those runs in parallel thirds, for example.

It's an instinctive love of a melody that people find undeniably cute. Another example is The Boy With The Thorn In His Side [The Queen Is Dead]. That was the first time I used a Strat on a record. I got it because I wanted a twangy Hank Marvin sound, but it ended up sounding quite highlify.

And then there was that submerged rockabilly strain.

That comes from a love of Chuck Berry's You Can't Catch Me. I've been trying to capture that same swing I'd better be careful because he'll probably sue me if he reads this. The way he sang against the bass and drums sounded so great to me as a kid. That, plus the soul swing of What'd I Say by Ray Charles. The Stones' 19th Nervous Breakdown is another one. It's a wicked groove - It really kicks. That's where my “rockabillv" influence comes from. Plus, obviously, the Elvis Presley Sun Sessions. Scotty Moore's playing on that is amazing.

You've got a light touch with the whammy bar, when you use it.

I have an up-and-down relationship with the whammy bar. I've been getting into really interesting things with feedback, and I like to use the whammy bar with that. I'm really into false harmonics, like steel players and Nils Lofgren play with thumb-picks. You know, where you touch the string an octave higher than the note you're playing with the left hand? I like to pick a note with the volume turned down, and then swell it right up.

Do you have any tips for generating feedback?

I've started to realize the importance of where my cabinets are placed in relation to where I'm standing. And when I get to a venue that has a wooden stage, I say, "Yeah, great!" especially if it's hollow. But if it's a rubber-covered stage or – God forbid! – carpet, then I'm in trouble. I nearly always keep my little finger on the volume pot, so if I hear the glimmer of something really interesting, I turn the volume right up; if it's not happening, I turn it down and try to find another note. I don't use a volume pedal – it's all volume knob. That's inspired by Roy Buchanan, Nils Lofgren and Jeff Beck.

You're using a lot of wah-wah these days.

I find that I approach it like a tone pot. The "whacka-whacka" sound was already done in the best possible way on Theme From Shaft, and then there's Hendrix, of course. Now, I find myself keeping my foot on it all the time, just letting it out slowly without thinking about it too much. Also, you can leave it on, opened slightly, without even touching it – that gives you a completely different tonal range. The Shoplifters break was the first time that I really discovered that. And if the filter is open in just the right place, you can get a harmonic to sing like a bird.

Is the music you're making with Bernard Sumner heavily sequenced?

Yes. I really like dance music, especially in the classic sense of the Fatback Band, the Ohio Players, and stuff like that. If it's a good song, I'll play alongside machines any day. I'm looking forward to coming to grips with sticking guitars on electro music. Also, it confuses people about what I'm doing, which I'm quite into. I don't believe in painting myself into a corner anymore, and I'm open to any kind of technique. [The Bernard Sumner album became the Electronic album, released in 1991.]

Originally published in Guitar Player, January 1990. Johnny Mar's book, Marr's Guitars, is out now.

Joe Gore is a guitarist and writer and a former editor for Guitar Player magazine. He has played on albums by Tom Waits, PJ Harvey, Les Claypool, Mark Eitzel, Tracey Chapman, Courtney Love, Eels and more. His book, The Subversive Guitarist is out now and has been acclaimed by Vernon Reid, Gretchen Menn and Dweezil Zappa, among others. For more information, visit his website.