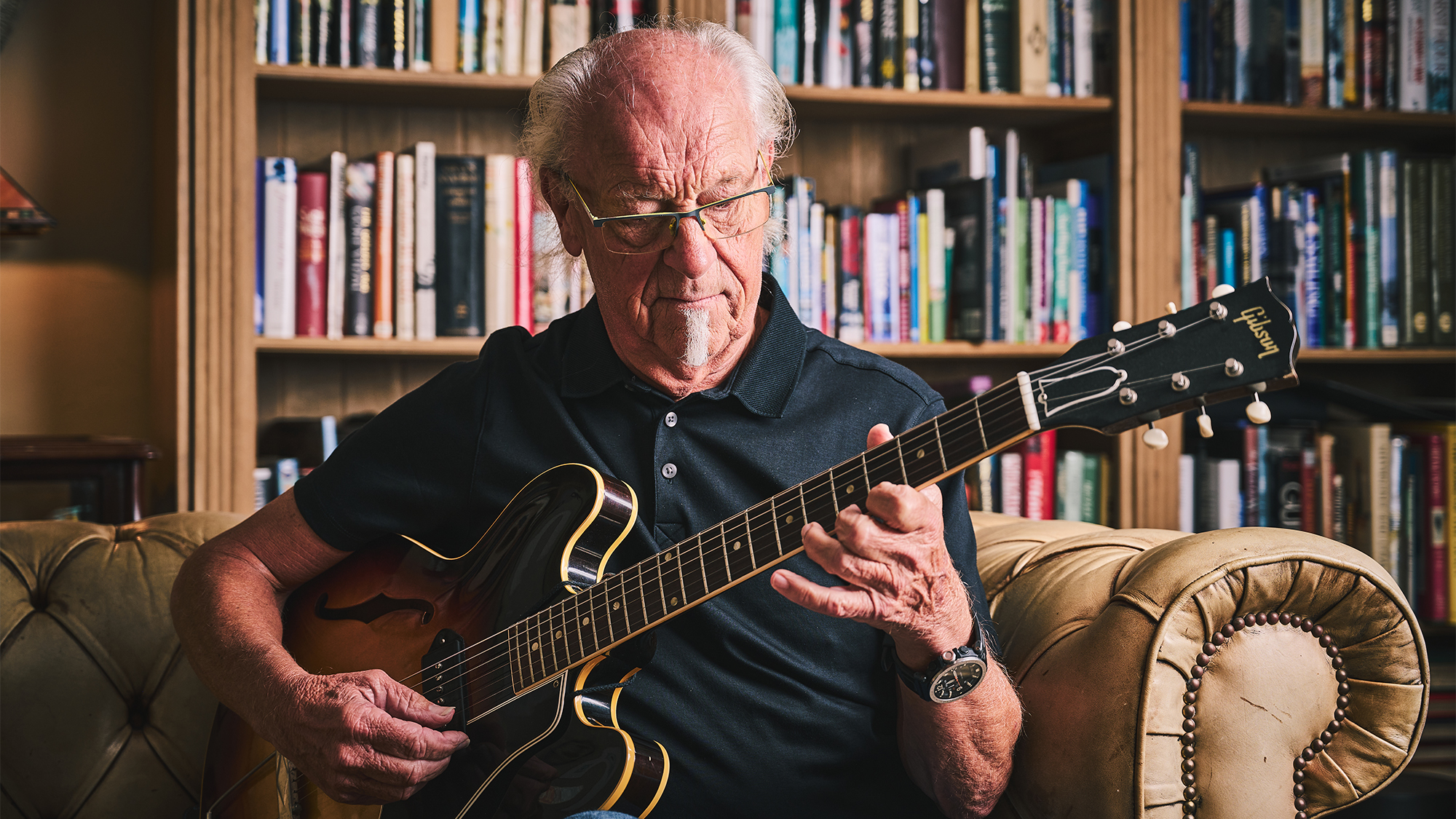

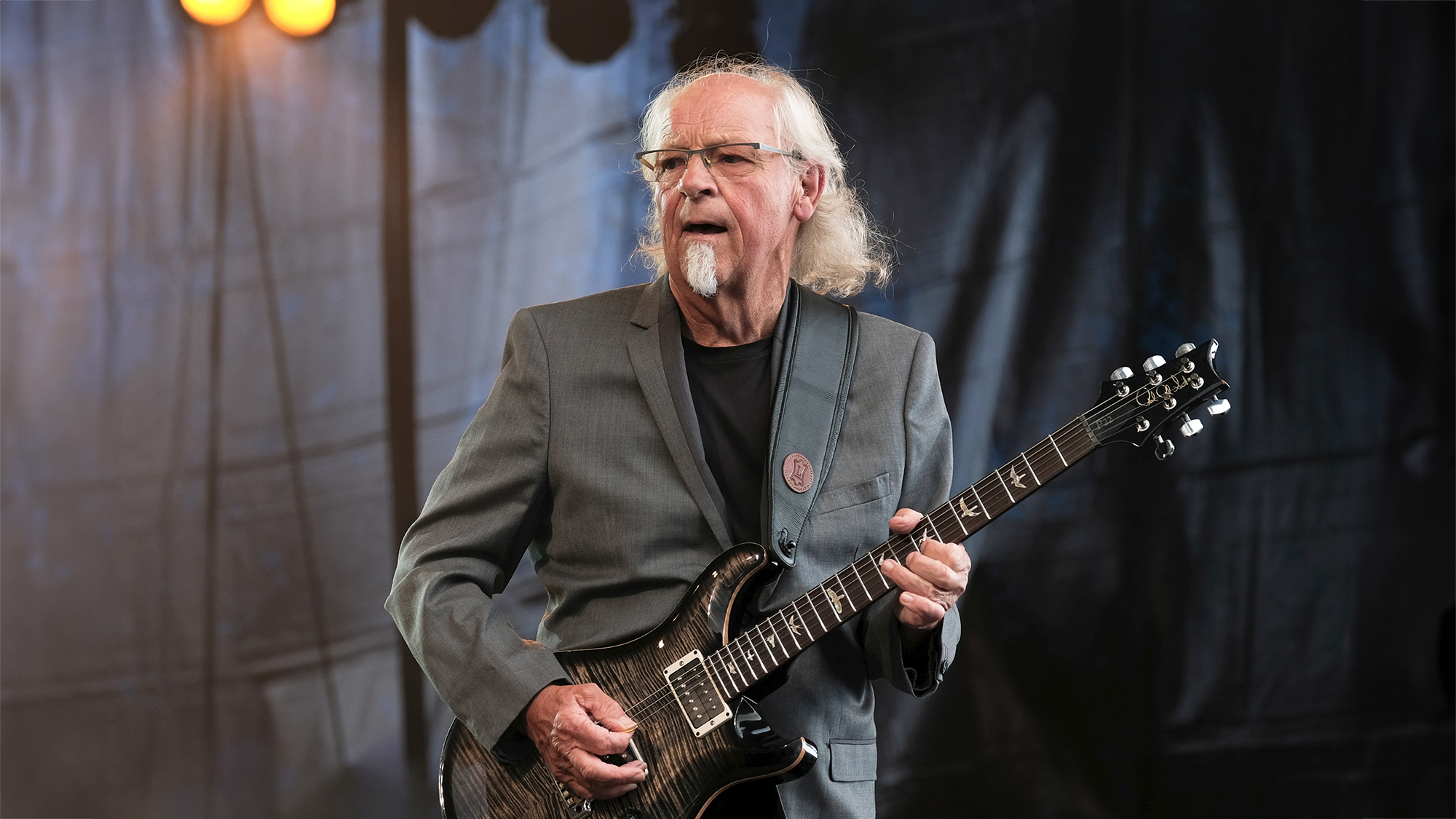

“He’s saying, ‘You know, I really hate my voice.’” As Martin Barre drops his memoir, the former Jethro Tull guitarist talks Jack White, Jimi Hendrix... and his secret gig with Paul McCartney

Available now in the U.K., Barre’s autobiography is heavy on guitars, gear and growing up

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A few days after the fact, Martin Barre is not yet aware that Jack White name-checked Jethro Tull as an influence during his acceptance speech for the White Stripes’ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. But the forebear is nevertheless pleased.

“That’s brilliant,” Barre says when Guitar Player informs him of the shout-out. “He’s great. He’s a great, talented guy. I have a lot of respect for what the White Stripes produced — my family as well.”

But far be it from Barre, of all people — a professed (accurately) “expert on Jethro Tull” — to be surprised by that, or any, accolade.

“I have an immense respect for the brand,” he says from his home in Lancashire, England, overlooking the moors. Given his history — nearly 45 years and 20 albums, including classics such as Aqualung, Thick As a Brick, War Child and more — Barre is right to “sort of picture myself as a flag-bearer, carrying the banner” with his own band since 2013, including a current acoustic tour in the U.K. He’s also released eight albums of his own and contributed to recordings by fellow Tull alumni Mick Abrahams (who he replaced in 1968) and Clive Bunker, as well as Paul McCartney, the late John Wetton and Ten Years After’s Chick Churchill.

“I’m intensely proud of what Jethro Tull was, and Jack White saying that reinforces my belief that we’ve left something behind that’s indelible. People have taken notice and it’s inspired them down the line, and that’s something to be really proud of.”

Barre, 78, has funneled his Tull expertise into a memoir, A Trick of Memory: The Autobiography of Jethro Tull’s Guitarist, just out in the U.K. and due during January in the U.S. The 182-page book takes readers from his early days, growing up poor in Birmingham and being introduced to music by his father, an aspiring professional jazz clarinetist turned engineer, as well as his older sister Jeanne. It traces his journey through the 1960s music scene, playing saxophone and flute as well as electric guitar in R&B bands and encountering the heroes of the day, before joining Tull in 1968 and making his recording debut on the band’s second album, Stand Up.

It’s concisely told, with plenty of details and anecdotes — some positioned as sidebars dubbed “A Tull Tale” — along with appendixes about his favorite Tull songs, performances and venues to play. He also gets into the weeds about his gear, from his first guitar and amp — a Dallas Tuxedo with a Watkins Dominator combo — to a chapter titled “Guitars, Amps and Instruments of Torture.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

So there’s a lot — a whole life, in fact — to talk about before Barre has to depart for his next gig, getting into the stories behind the story he’s told...

Why a book?

I figure everybody has a story, and the worst thing that can happen is you don’t leave that behind and that story’s lost forever. As reluctant as I am to try and pretend that my story’s important, I want it on record. … Not on record, but for those who might be interested in just what happened in the ’50s and the ’60s and the ’70s and how that developed into what and who I am now. That’s why I did it.

What’s the story you wanted to tell?

The book is biased to the earlier part [of his life], and I leave the latter years to the abundant amounts of material that’s online about Tull, with all the facts and figures.

So it’s more about the preamble. In those days every event had the biggest impact, and the people I met had a big impact on me as well. They were formative years, and they’re quite dear to me. I just feel now, later in life, the things that are most important to me are those more private parts.

I’m not a rock star; I’m not a guitar hero. And, every day, to live a very ordinary life where 99 percent of the people I come into contact with either don’t know who I am or don’t care what I do...

There’s evidence, including in the book, that argues otherwise, you know.

[laughs] The achievement is history, you know? I can tell people that I played in Shea Stadium. I can tell people that we did three nights in a row at Madison Square Garden, we played in front of a quarter of a million people at the Isle of Wight, I played onstage at the Royal Albert Hall — and I’m so proud that I was able to do that. I don’t disown it; I’m really proud to have been there and privileged to have done those things. I think about them enough, but I don’t dwell on it.

I just feel now, later in life, the things that are most important to me are those more private parts.”

— Martin Barre

My personality isn’t rooted in who I was and what I did; it’s rooted in who I am today and what I’m gonna be like tomorrow. What’s important to me is that I play the best I can and give a great performance and the quality of the music is of the highest standard I can produce. That’s my job, and I’m very intense in the way I approach it. But when I close the door at the end of the night, I’m just the guy next door. I don’t live a rock-star life, and I’m quite glad I don’t.

The book is definitely not a tell-all.

I just wanted it to be factual and positive. I think gossip is very frivolous, and it’s very private and subjective. It has no substance to it. The experiences I’ve had are sort of private little events, and I change my mind about them. One day if I think of something that happened as being terrible and how bad it was for me, then another time I may weigh the pros and cons and look at it from a different viewpoint.

I haven’t hidden anything at all, but I haven’t gone into personal relationships to a great degree — and there’s a few things that were redacted, expunged by the people who publish and proofread. There are a few fruity anecdotes that are missing. They’re not forgotten, just maybe something I’ll do another time, maybe a volume 2 when I live on a small island in the South Pacific. [laughs]

You talk about focusing on the early days, and it’s very striking and heartwarming how supportive your family was.

My dad had a tough life, but we were never made aware of it when we were kids. My parents put me and my sister before anything. They sheltered us from whatever things they were going through and gave us the positivity to be able to do what we were able to do.

My dad loved music; that’s what he wanted to do when he was 14, 15 years old and he couldn’t do it because his parents made him go into the family factory at an early age. So his passion was squashed, and he never talked about it. When I threw away my to-be career, my schooling and college to do something frivolous like being a musician, he didn’t say a word.

You write in the book about being blown away watching the guitar player in Mike Sheridan and the Nightriders at a youth club when you were young and then wanting to start playing yourself. What was the allure of guitar back then?

It was my sword. It was my... I could be really poetically, dramatically pretentious and say that like when medieval soldiers would fight for king and country, that sword was their emblem, their strength. That’s what the guitar was for me; it was my way out of what I didn’t like about what I was doing. It was the thing that was going to open up doors, possibly — and I could never know how many or how big those doors were going to be. I just saw it as something I could really put myself into.

I didn’t particularly love music enough to think that, Oh, I have to play music, and the guitar is going to be my instrument to get me on that pathway. I think it was just that guitar was a symbol, if you like, of a bit of freedom.

I didn’t particularly love music enough to think that, Oh, I have to play music. I think it was just that guitar was a symbol, if you like, of a bit of freedom.”

— Martin Barre

Were you a natural talent?

Oh no, no. Still not. I work on all my faults every day, and I do every day. I’m so far from being good enough for myself that it’s way off there. [points toward window] If you talk to people who I knew in those days, they always say, “Oh, yeah, you were always playing your guitar,” and I don’t remember it being like that. It was a slow process, ’cause there was no information. There was no YouTube or way to Google how to play “Stairway to Heaven” in two minutes flat. You had to work it out yourself, with no help.

But that’s great. You got to learn the neck of the guitar. Everything was a discovery, and I’ve always said that kids now might be in a place in a year, whereas it’s taken me 20, 30-plus years to get there. But I figured it out myself. I didn’t learn it from a book or a YouTube channel or from a teacher. I figured out chords, scales, all the beautiful relationship between all the elements of music. It became mine. Not somebody else’s.

You had some early and personal experiences with Jimi Hendrix.

I knew of his playing before I met him. We were in Rome playing soul music and some kid came from London to see us play and he had this sort of acetate demo disc. He said, “Have you heard of Jimi Hendrix? Have you heard his new single?” “No, I haven’t.”

So he played it, and it was “Purple Haze.” It was just a demo and I’m listening and I can’t understand how he’s made that sound. It was such a beautiful thing. And, of course, he tried to re-record it and he couldn’t get it any better, so they used the demo. I just remember listening to it, and it was such an alien situation, but it had such an impact on me.

And then you got to share a bill with him.

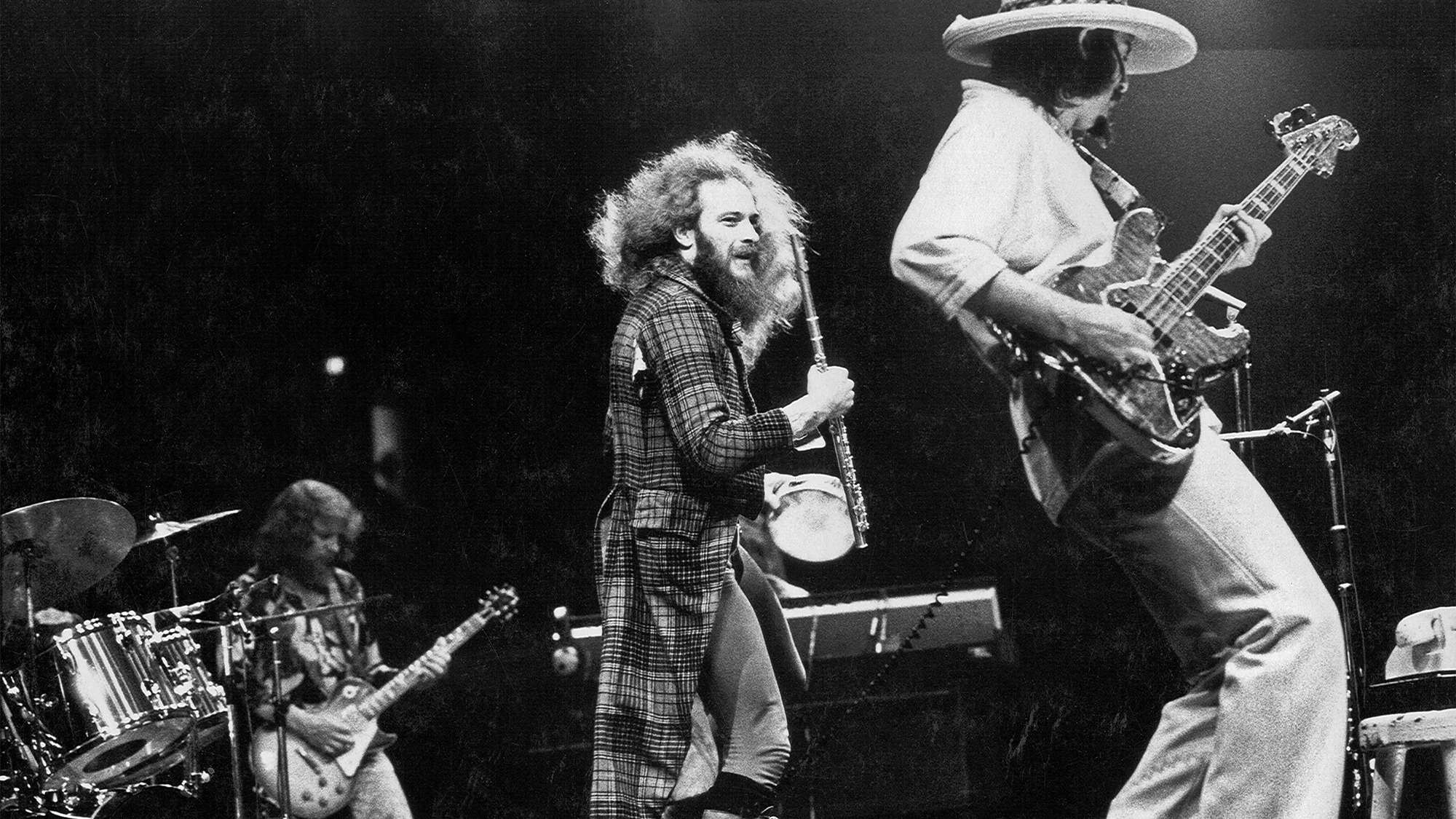

It was January 1969 and Tull was gonna be the support band with Hendrix onstage, and I’m absolutely terrified. I’d never come into contact with anybody more famous than Ian Anderson. [laughs] And I was in awe of Jethro Tull before I joined them because they were the best band I’d ever seen onstage, but this was a step beyond imagination. Here we are flying to Copenhagen, and that night I’m gonna meet the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and there he was onstage, and he’s kind and humble.

He’s interested in me and we’re talking and he’s this really nice person, and he’s saying, “You know, I really hate my voice.” And I’m like, Is this really Jimi Hendrix?

I didn’t know what to say. I said, “Your voice is unbelievably good,” but he truly hated his voice. It was an early lesson in humility, in him being accessible. He had no baggage. He didn’t have anything but himself to give, and he was beautifully honest. It was inspiring that somebody that good could be so nice. That was my first lesson of many — not all of them learning something positive.

Oh? What were some of those?

I can’t say! [laughs] I’ve met some of my heroes; let’s just say I’ve been disappointed in them. But you learn from everything.

I’ve met some of my heroes; let’s just say I’ve been disappointed in them. But you learn from everything.”

— Martin Barre

You say that it’s important not to look for influences, lest you wind up just copying something. Explain that philosophy.

Everything that inspired me is music I can’t play, so by default I can’t copy it. It’s something I want to attain and would love to do, but it’s always something a little higher up. Three weeks ago I went to see Billy Strings at the Royal Albert Hall, and between him and his mandolin player — ’cause I love playing mandolin — I was grinning from ear to ear. Some people get depressed when they hear somebody so much better, but I just love the experience.

I’ve always really enjoyed watching somebody do something masterfully well. It inspired me, the need within myself to do better. I’m like, Right, you need to do better. I thought I did, and hearing them proves that.

I go to classical concerts to listen to the flute players, and I take a pair of binoculars and I’m on them the whole night, just loving every second because they’re amazing, amazing musicians, and I’m just a lowly, sort of wanna-be. I want to be a better flute player, and hearing them tells me why I want to be a better flute player.

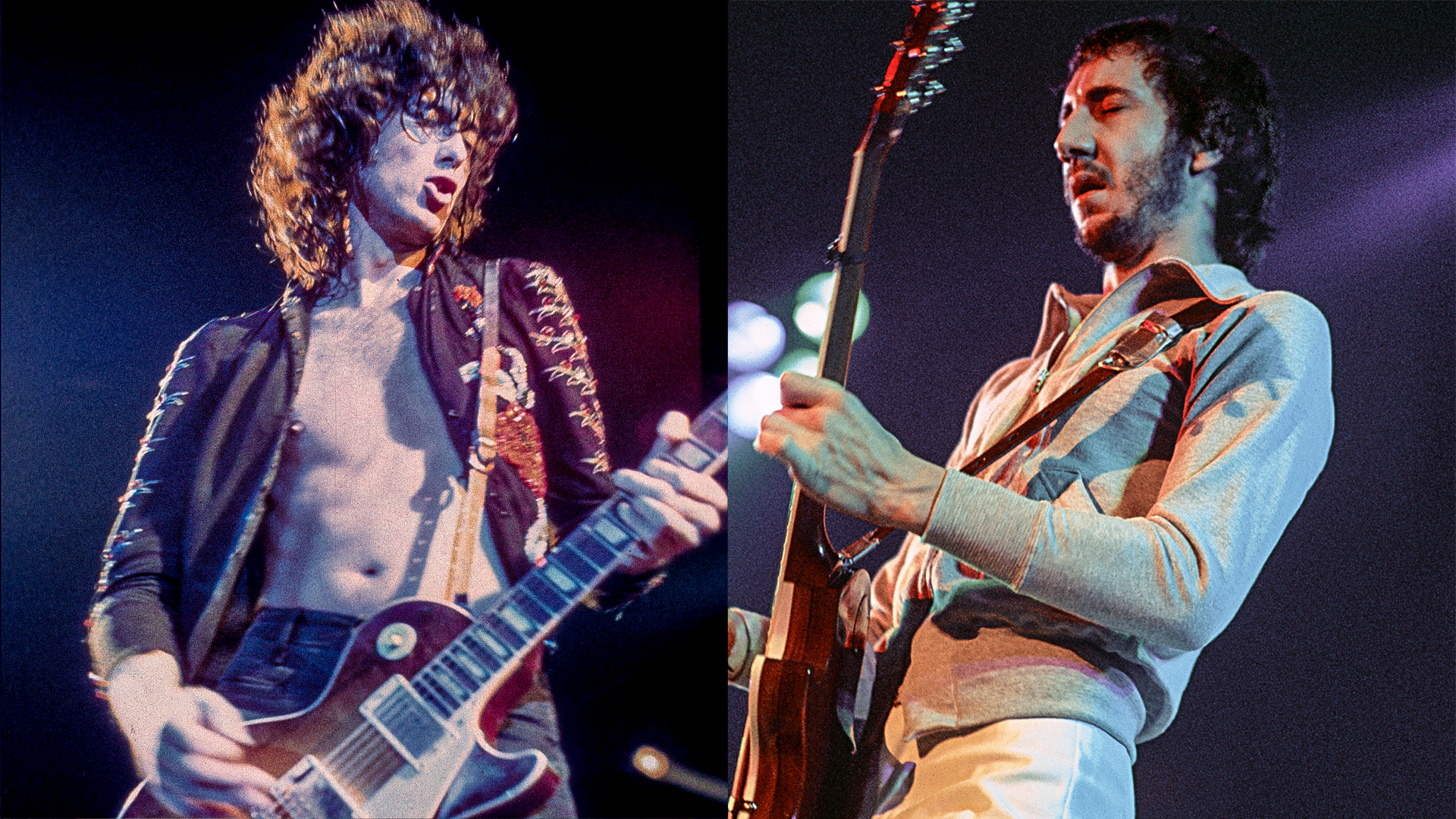

You acknowledge some influence from Leslie West, however. Why is he an exception?

Yes, he’s very hard to ignore. I loved him to bits, and I think it was his attitude that influenced me more than anything. In that era, sort of very early ’70s, most bands were fairly distant and disconnected. There was a lot of competition and the biggest thing was the support group tried to blow the main act off the stage. That’s what you were trying to accomplish, so it wasn’t the friendliest of atmospheres.

Mountain was the support band, and they didn’t give a shit they were the support band; they were having the time of their lives. They were such a tight unit, so friendly and supportive of each other. You’d watch them onstage and the communication, the smiling, the little things they were doing between them was really special.

And, obviously, his playing was so beautiful — his phrasing and his beautiful pitch and vibrato, understated but yet beautifully performed. I wasn’t going to be Leslie West number two, but some things I did emulate, just learning from it rather than copying. And we became friends, as you do.

Also on the hero front, you write a bit about the cloak-and-dagger of being part of Paul McCartney’s Atlantic Ocean project in 1987. What was that like?

It’s a tricky one because I had to sign an NDA, and I never had or a copy of it, or lost it, so I’m not quite sure what I can say. I had a wonderful week with him. It was magic, the dream of my life come true, and it came at a great time because things were being a little taken for granted in the Tull camp at the time. We were in the middle of doing some album, very immersed in it, and I went to Ian and said, “Oh, I need a week off. There’s something I’d like to do.” And, of course, when I told him it was Paul McCartney… [laughs]

But it was nice for me, and it made me a stronger person because it was a terrifying experience to be in the presence and working for somebody on that level. But he was a fantastic person, just amazing, just full of energy and music never stopped. There are a couple stories — nothing nasty or negative, just sort of slightly amusing. If there’s a volume two [of the memoir] I’ll have to call his manager and say, “Can I tell the story?”

It was magic, the dream of my life come true, and it came at a great time because things were being a little taken for granted in the Tull camp at the time.”

— Martin Barre, on performing with Paul McCartney

Did you feel any desire in the book to set the record straight about Jethro Tull and how the band worked and your contributions?

No, because if somebody wants to know, they’ll find out. It’s all there to absorb. You can hear everything. You can hear what I played, you can hear what John Evan played. You can hear what Jeffrey [Hammond Hammond] played, what Ian’s playing. There’s always going to be people who don’t like me and what I do and don’t like the fact I’m doing it without Ian, and vice versa. Who’s right? They’re all right, ’cause everybody has their own opinion and are entitled to have it.

What was the creative dynamic and process within Tull? Were you assigned parts or given free rein, or...?

It’s always been a mixture of both. Some things… like “Aqualung,” he wrote the whole riff, and the solo section I wrote, sort of based on the chords of the verse. Thick As a Brick was full of ideas from everybody — a lot from John Evan, who came up with amazing Hammond [organ] parts and ideas we developed into some of the instrumental passages.

So there was no formula. If I came to Ian with some idea he would listen. He would take on board everything that was on offer, and be very fair about it as well. There was no resistance. It was all the mixture of ideas and people working together.

Any favorite anecdotes about a song that developed from one of your ideas that became more than you may be expected?

“Paparazzi” [from Under Wraps] was one. I think later on in the years I was more confident with coming up with big ideas. I was beginning to write more rather than just practice and do a concert appearance. Under Wraps, with me and Peter [-John Vettese] and Ian was just a very enclosed situation where we were constantly thinking up ideas.

One day as we sat there, sort of having a cup of coffee, I said, “Look, I’ve got this riff I’ve written. Do you want to hear it?” “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” So I played it and they loved it, and that became the song. That was great. It was the first Tull song I wrote, and I loved having a bit more in the cooking pot.

Any further insights now, after doing the book, into why things went the way they did with Tull back in 2012?

No. I understand it completely because I had to analyze it for my own benefit. I needed to understand what was happening, why it was happening, how it was happening and put it into perspective. I didn’t want to be the injured party. I didn’t think I deserved to be. I just needed to know my own mind and what it was all about.

And I’m fine. I’m at peace, mentally. I know other guys that have been in Tull and had sort of an abrasive end and didn’t do so well coming to terms with it. It’s a tough business.

You’re kind of the guy keeping the Tull music alive in a way, because you’re pretty constantly out there and the current incarnation is a bit more episodic. Is there an appreciation from the audience that you’re doing it?

I don’t ask for reassurance. My reassurance is walking into a gig and, “Oh, you’re sold out tonight,” and I’m like, “Yeah!” That makes me feel great.

But, yeah, I’ve got a lot of self-belief, and it’s based on how powerful the music can be. I know I’ve got a great band. I know how good they are. But while everybody likes to hear good things, you must never, ever, ever take it to heart 100 percent because for every person that comes up and says, “You’re one of the most underrated guitar players, you are amazing, blah, blah, blah” you’ll get another one who, whether they say it or not, will think the exact opposite. You can’t believe one and not the other; that’s how I deal with it — “Well, that’s nice of you to say. It’s not particularly what I think, but I appreciate that you’re enthusiastic.”

There’s a lot of instrument and equipment detail in the book. Are you a big gearhead?

Less than a lot of people, mentioning no names. I don’t hold numerical values to what I have. I don’t have a valuable collection of guitars. I have maybe 10 vintage, but I love them and they sound great and they play great, and that’s their primary function being in my world. I use them and play them and they do a great job for me, otherwise they wouldn’t be here. None of my guitars are in cupboards; they’re all there to grab. And they come and go; I buy a guitar, sell a guitar, love one, love another more.

Are any of your vintage guitars from all the way back in the day? Do you still have the “Aqualung” guitar or something?

No. I do know where those guitars are, but I don’t miss them. They did a great job, but to be honest I moved on because I found something that did the job better. People say, “You’re completely stupid,” and maybe I am, but that’s what an instrument is to me. You give it a lot, it gives you a lot back, you move on. There’s no snobbery in me.

Are any of those older guitars owned by any one of note?

[shakes head] I’ve heard the names. It’s people who don’t play them; they just know what they’re worth.

What’s coming up for you?

Gigs, of course. I’m booking into 2027. And I want to do a record. I haven’t done a solo record for a long time [since Roads Less Travelled in 2018], so I want to spend a lot of time writing and recording. I’ve got two live albums I want to release as well.

Will we see you across the pond next year, maybe as the book comes out over here?

I’d like to come to America to talk about the book. America’s on hold right now. I’ve been there a lot done a lot of touring... to the detriment of other areas. So I need to redress the balance. I want to sit and think, and I want to come back with something that’s gonna be amazing, because I think it needs to be.

I’ve done a lot of tours with different headings — an Aqualung tour, a 50 years tour, a History of Tull. I need something that’s really going to hit the headlines in the Martin Barre Band world.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.