Martin Barre Reflects on the Recording of Jethro Tull's 1971 Prog Milestone, ‘Aqualung‘

How a little naïveté, a lot of preparation, and a '58 Les Paul Junior helped Barre track one of prog's finest albums.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the annals of progressive rock, Jethro Tull’s Aqualung stands apart from much of the meandering music that populates the genre. The album came out 50 years ago, in 1971, a year that also heralded the arrival of other prog-rock classics, such as Yes’s Fragile, Genesis’s Nursery Cryme, and Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Tarkus.

And yet, Aqualung has always been an album that any rock-and-roll fan could love. That undoubtedly comes down to Jethro Tull’s singular musical style.

While bands like Yes and Genesis were making music that was both classically inspired and often redolent of English pastoral sounds, what separates Tull from so many of their prog contemporaries is that they never forgot they were playing rock music – albeit rock music imbued with the group’s blues, jazz, and folk roots.

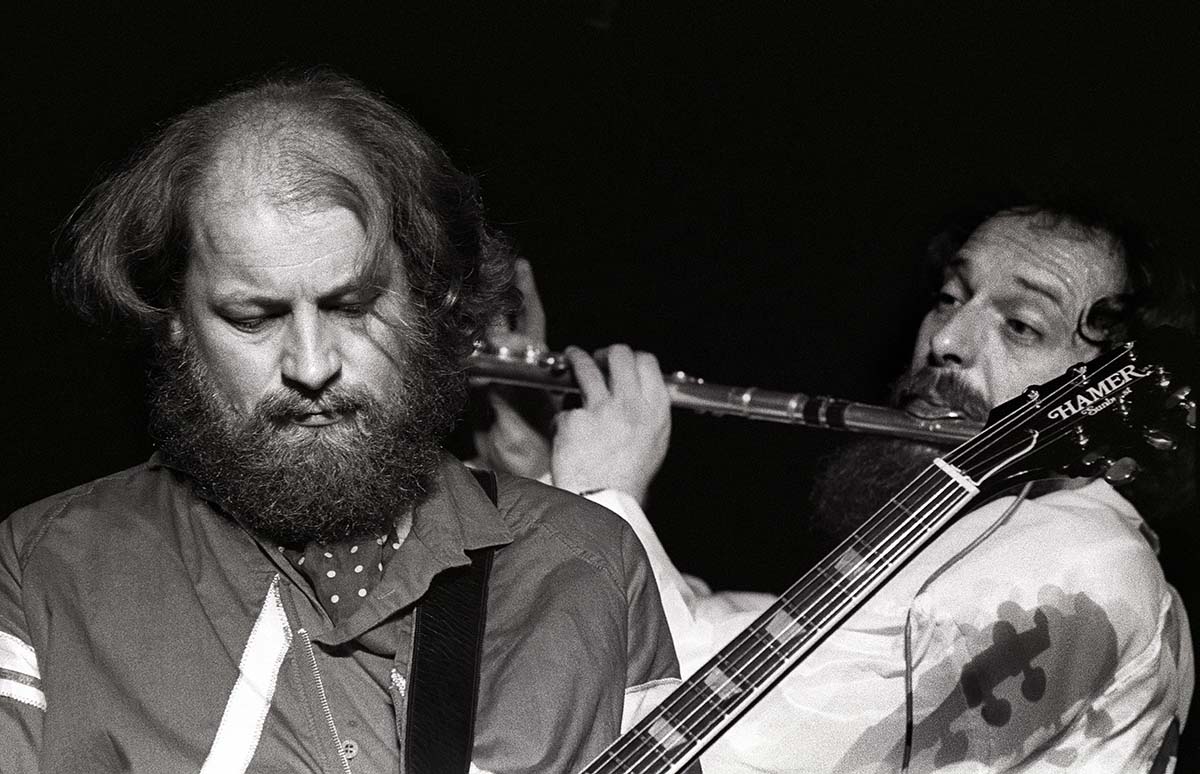

A rich and varied collection of songs, Aqualung has often been described as a concept album, a claim that singer and primary songwriter Ian Anderson refutes. However you choose to view it, Aqualung rewards repeated visits, the layers of flute, keyboards, and – especially – guitars revealing more with each listen.

Tull’s previous albums had featured acoustic guitar but never to the extent that they are present on Aqualung, where folk-flavored acoustic musings like “Wond’ring Aloud” and “Mother Goose” contrast with heavier classics like “Locomotive Breath,” “Cross-Eyed Mary,” and “Aqualung.”

The combination of Anderson’s acoustic guitar and guitarist Martin Barre’s hard-hitting electric riffery coalesced into the perfect distillation of what would become the staple ingredients of the prog genre.

Prog, of course, is short for progressive, and that description is particularly apt where Aqualung is concerned. As Barre explains to Guitar Player, “This record came at a time when we’d turned the corner on the naïveté of learning to become musicians, and more was then expected of us. We needed to progress.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

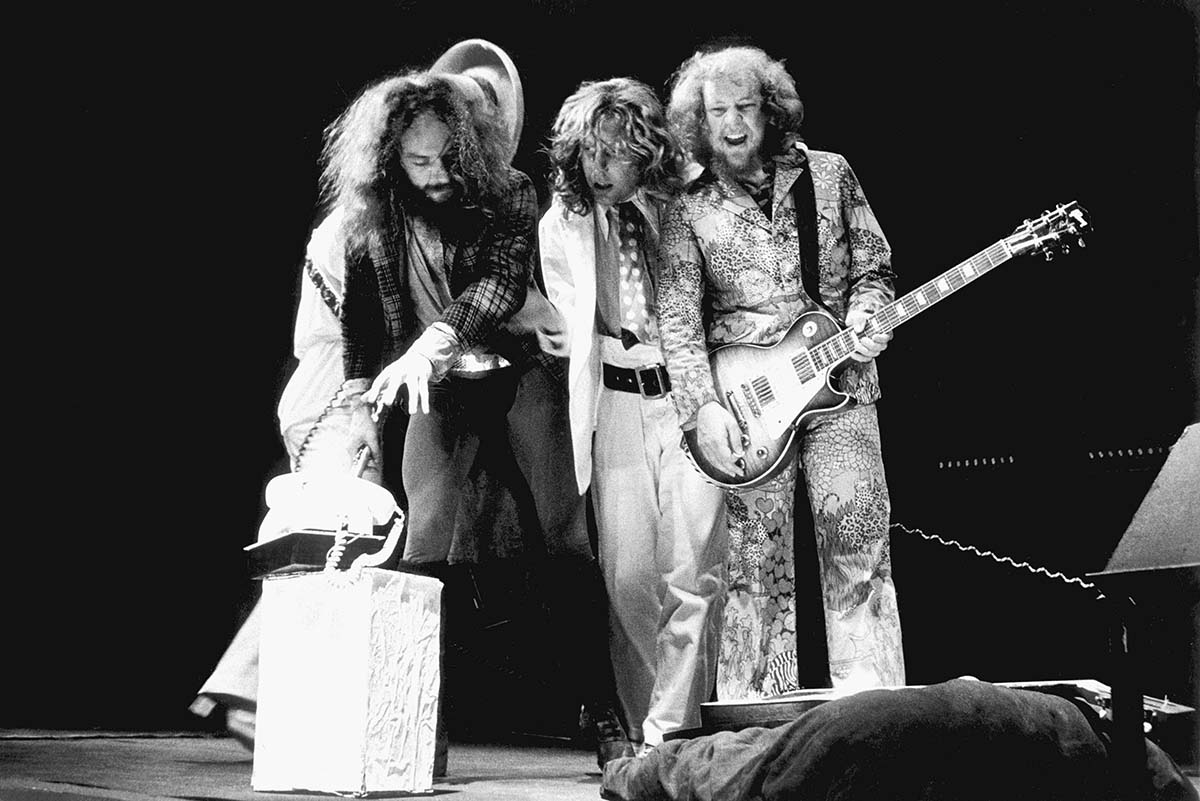

Having launched in 1967 as a blues group with shades of folk and jazz, Jethro Tull had by 1971 plied their musical stylings for three albums, building a strong following and enjoying commercial success in their native England.

The blues elements had taken a backseat to jazz and folk over the course of their first three LPs – This Was, Stand Up, and Benefit – but the disparate genres in their music hadn’t quite coalesced into a singular musical vision.

This record came at a time when we’d turned the corner on the naïveté of learning to become musicians, and more was then expected of us. We needed to progress

That changed with Aqualung. By the time recording began in earnest at the newly opened Island Studios, founding bassist Glenn Cornick was out, replaced by Jeffrey Hammond, a former mate of Anderson’s who had been the subject of the occasional Jethro Tull song. The group had also picked up keyboardist John Evans, who had guested on previous records.

As Anderson explained in a 2019 interview, “With the changing of some of the musicians, of course there comes a new lease on life as people bring their own idiosyncrasies, musically and stylistically, and perhaps technically, into the equation, which may offer a new horizon.”

Which is simply to say that the Aqualung lineup, which also included drummer Clive Bunker, was compatible with respect to the members’ personalities and attitude toward the music, and their efforts paid off.

Aqualung is Tull’s best-selling record, with sales of approximately 12 million, according to Anderson’s recent estimate. The album gave the band its U.S. breakthrough, paving the way for international success and acknowledgment.

The astounding number of artists who have cited Aqualung as a major influence – ranging from Joe Satriani to John Lydon – is further testament to the album’s perennial relevance. Aqualung has continued to earn accolades with subsequent reissues, in particular renowned producer Steven Wilson’s 2011 remix, which shone new light on the 20th century masterpiece.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the album’s 50th anniversary was supposed to be celebrated on the road. Barre had planned to tour the album with his band, playing all the tracks in sequence. Global pandemic restrictions have temporarily put paid to that idea, although it is expected to be rescheduled as soon as we can all return to the live arena.

“I’m hoping that we’ll be able to do that next year now,” Barre says. “It might not be exactly the 50th anniversary, but I think people will be so glad to see live music again that they won’t want to quibble about that.”

When was the first time that you heard the songs for the album? Would you have been given demos of rough ideas by Ian, or would he demonstrate them to you?

Jeffrey had only just joined the band and he couldn’t play; he wasn’t a musician. We bought him a nice Fender Jazz Bass, and we put chalk marks all up and down the fingerboard to give him a guide. Me, Ian, and Jeffrey spent a few weeks in Ian’s flat in Highgate [London], teaching Jeffrey the entire electric parts of the album.

It was a long process, but the nice thing about that was that we got very familiar with the songs. You can get inside the riff when you’ve really soaked it in, so that it becomes second nature. By the time we got in the studio, the entire album was ingrained.

It was a long process, but the nice thing about that was that we got very familiar with the songs. You can get inside the riff when you’ve really soaked it in

It must have been useful in working out what you would play and how your parts would ultimately fit together.

Yes. Ian and I knew the basics, but there was a lot of repetition. There was a lot of pressure on Jeffrey, and I think with me and Ian helping him, it ignited a lot of ideas about arrangements and ways to play things. It ultimately meant that there was more preparation for this album than most of the rest, particularly in our early days.

Ian was a very capable guitarist. Did he play the acoustic tracks on the album, or did you divide the duties?

In those days, Ian played all of the acoustic guitar on the album and I played the electric parts. On Benefit and Stand Up, I played a little acoustic and Ian played a little electric, but that was more for fun, really. Just for variety.

Given that, you have often said if you didn’t nail the solo quickly, it would become a flute solo instead. Are there examples where you look back and think a part would have been better if it had been a guitar part instead?

[laughs] I don’t give anything away, believe me! That was more said in jest. The thing behind it was that we were dealing with 24 tracks, and there wasn’t the availability that you have now for keeping endless takes and having the luxury of picking the best solo.

You might be able to keep a couple at best. It meant that you had to nail down your solo in one take. It was good in that it meant that you had to have commitment. Even now, most of my solos are first or second take, because that’s when it’s fresh.

I used a 1958 Gibson Les Paul Junior... In those days, one guitar was deemed to be all you needed for everything

How many takes would the band do of a song before they decided it wasn’t working, or would everything get worked through to completion?

We never abandoned anything in our whole career. We might do an album and have a couple of tracks that we didn’t have space for, but we always persevered. Backing tracks took time because we weren’t perfect; we were human.

We spent a lot of time working on the backing tracks on Aqualung, but the overdubs and solos for the songs would have generally been first or second take. That was the fun part; getting the backing tracks down was the tense part of the process. We would never have given up on a song. To admit defeat musically was not on our agenda at all.

What guitars did you use on the album?

I used a 1958 Gibson Les Paul Junior that I’d only bought a short time before we started recording the album. In those days, one guitar was deemed to be all you needed for everything. [laughs]

It was inspired by Leslie West, who was a big influence. I knew him really well and we talked about sounds and gear a lot. It was very sad when he passed away recently.

What amps and effects did you use?

We were all using Hiwatt. I had a 100-watt head going into Hiwatt 4x12 cabs. I was experimenting, so I also had a small Fender Super combo that I used for “My God.” I had a tiny amp that was made in the mid ’60s that I did all of “Cross-Eyed Mary” on.

It’s about six inches by eight inches and doesn’t have a name on it, but I’ve still got it. The Hiwatts didn’t overdrive particularly well, so I had a nasty treble booster that was always breaking down. I turned to Marshalls soon after. Jeffrey Hammond inherited one of Glenn’s old Hiwatts for his bass.

In terms of effects, there wasn’t much choice at the time, was there?

No, and that has stayed with me. I’ve dabbled with pedals, but I always come back to the pure amp sound. Obviously, all gear has improved enormously since then. I think if you start using pedals, they can become a bit of a crutch.

If your sound is derived from a lot of pedals, every time you play that song you’re stuck with using the same setup. I just want to think that I can plug straight in and do everything that I need to do.

Many of your parts are integral to the songs, but you didn’t get any co-writer credits. Did that frustrate you?

It never bothered me. The songwriter, particularly in those days, was the guy who came up with the chords and the lyrics. Arranging was just something everybody did. I’d have hated to have been in a band where everybody was given their parts and that was basically what you had to play.

With Tull, we all had a lot of freedom to come up with parts and ideas. Nobody would have ever produced a stopwatch and said, “That 10 seconds of music there was my idea.” [laughs]

We were living a dream, playing in a successful band, and the money didn’t come into it, which is what talk about division of credits usually boils down to. We knew why people liked us, and a large part of that was because of Ian’s songs.

I would never play like that now. I don’t mean that in a derogatory way, but there is a naïveté there, which is part of the essence of the album.

If you could time travel back to the sessions, would you change much of what you played?

I would change a lot. I listen to it and I think, Ouch! [laughs] It is a historical piece of music; you don’t get the chance to change things. You play in the moment. What you did becomes an important piece of music, although you don’t know it at the time. I would never play like that now. I don’t mean that in a derogatory way, but there is a naïveté there, which is part of the essence of the album.

There have been a lot of remixes and reissues of Aqualung, particularly the work done by Steven Wilson. What would you say is the definitive version?

The terrible thing is that I’ve never really sat down and listened to the remixes. I never sit down and play a Tull album all the way through. I’ll play particular tracks if I’m working on them for the live set, but I’d listen to the original version to make sure I’m not missing something that was on there.

People tell me that the remixes are incredible, because he has taken the ingredients that are already there and made them clearer. If, for example, Steve had called me up and said could I re-record a solo – not that he ever would of course; maybe just for a bit of fun – I’d never do that, because then it wouldn’t be true to what the album was, even if I thought I could do a much better solo now.

I listened to all of the remixes in preparation for this interview. I think it is akin to the restoration of an old painting – the way the original colors are so much more vividly realized. There is greater clarity of detail, perhaps.

I think that was a great thing that Steven did. I think if something changed the dynamic of the original album from how it was originally released, that would go too far, but I think polishing what was there is a very worthwhile process.

There seems to have been quite a lot of unused material which has turned up on the various reissues. Who made the final decisions regarding which tracks did and didn’t make it onto the record?

Everything that was recorded at Island Records studio was used on the album. [Rehearsals, held at Morgan Studios in London with Cornick on bass, were also recorded.] I know a lot of extra tracks have turned up on reissues, but, to my mind, if they weren’t recorded in those original sessions, they aren’t really a part of Aqualung. There were no “failures” which didn’t make the cut.

It has often been reported that there were a lot of problems with the studio itself, which was a brand-new facility. Did you ever think it might be easier to go to another studio instead?

I think we were booked and committed to being there. It was a very difficult album to make. There were a lot of problems with the studio. Every time something happened, we thought it was a one-off, until it happened again. [laughs] Things didn’t grind to a halt; it was just annoying, as one thing after another didn’t go smoothly.

Some of our performances weren’t 100 percent as well, which meant, as I said, that there was a lot of work involved in getting the songs right.

Gear broke down, and back in those days the control room was out of bounds for the musicians, except to listen back to a track. We’d be on the other side of the glass watching the guys in there engaged in discussion about what had gone wrong or something. We wouldn’t know what they were saying.

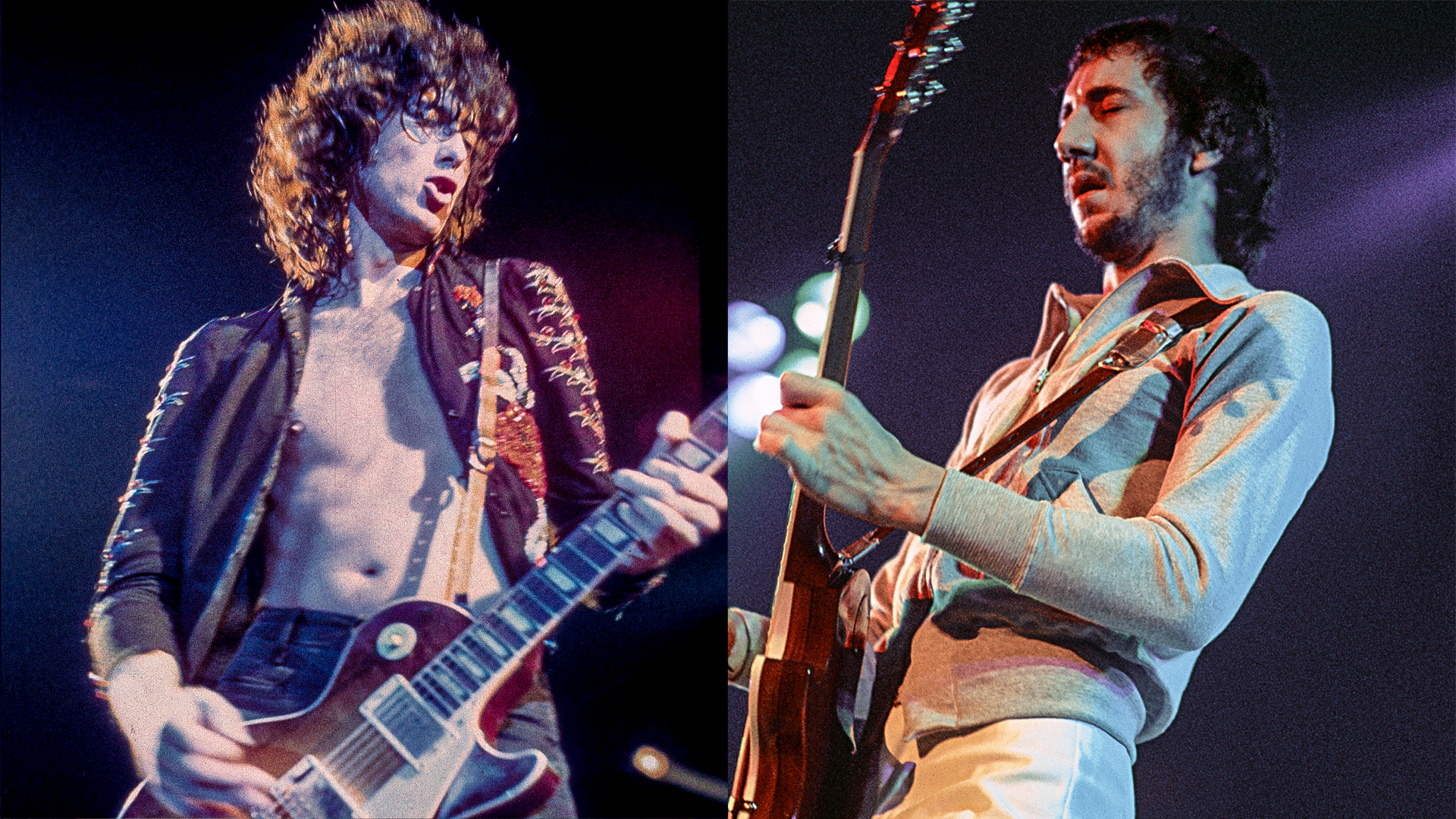

The solo on “Aqualung” is justifiably famous as one of the all-time great rock solos. I know you’ve mentioned Jimmy Page popping up in the control booth while you were playing it and being almost thrown for a moment. Have you ever discussed with him how he could’ve ruined one of your most iconic moments?

[laughs] No, because he left before I finished. I’m sure he understood that when you’re out there doing something, you need to get on with it. The funny thing about the story is that Zeppelin had been in the studio, in the basement, for over a month working on Led Zeppelin IV, and we’d never ever seen any of them.

It just happened that the moment he chose to pop in was whilst I was recording that solo. I either had to put my guitar down and say “hi” or carry on with the solo.

I think you made the right decision. Do you think your familiarity with the song, due to the lengthy period spent working with Jeffrey, helped you nail the solo so quickly?

I think it wasn’t until fairly late that we thought we’d have the solo in the middle, so I hadn’t been thinking about what I might play. Once we’d decided on having a solo, I went into the corner of the studio for about an hour thinking about the half-time part and arranging the solo based on the chords. It was fairly spontaneous.

It is interesting to compare the solo on “My God” with the earlier take on the Steven Wilson reissue. The second take is much more explosive. Would that have been a conscious decision?

I always think when I hear something back that I could probably improve on it. I never actually wrote a solo, with all the parts worked out, but certainly I’d see opportunities to refine what I did if I took another pass at it.

The Steven Wilson remix includes a much longer version of “Wond’ring Aloud” than the fairly short piece on the album. Was that a space consideration?

The longer one is much more satisfying. I remember us doing it, and I loved the longer version. I think it needed the full version. Maybe it was a consideration regarding the limited amount of space on vinyl, but I have a feeling it was Ian’s preference to use the shorter version.

When you were recording “Locomotive Breath” and “Aqualung,” did you have the sense that they were going to be such monster tracks in the Tull canon?

No, not in the slightest. Particularly with “Locomotive Breath.” That was quite a hard one to get down. Ian played a simple bass drum part to form the backing track, and then Jeffrey, Clive [Bunker], and myself added the rest of the parts. I played all the guitar parts, but Ian added a few phrases to complement the vocal line during the mix when I wasn’t present.

It was important to get a driving relentless feel to the track. There was another version with a click track and just me playing the chords. We had no concept of what would be accepted, but then we never had in the career of Tull. We just did the best we could possibly do. We were a live band, and we just wanted to get the record finished so that we could get out and play the songs in front of an audience.

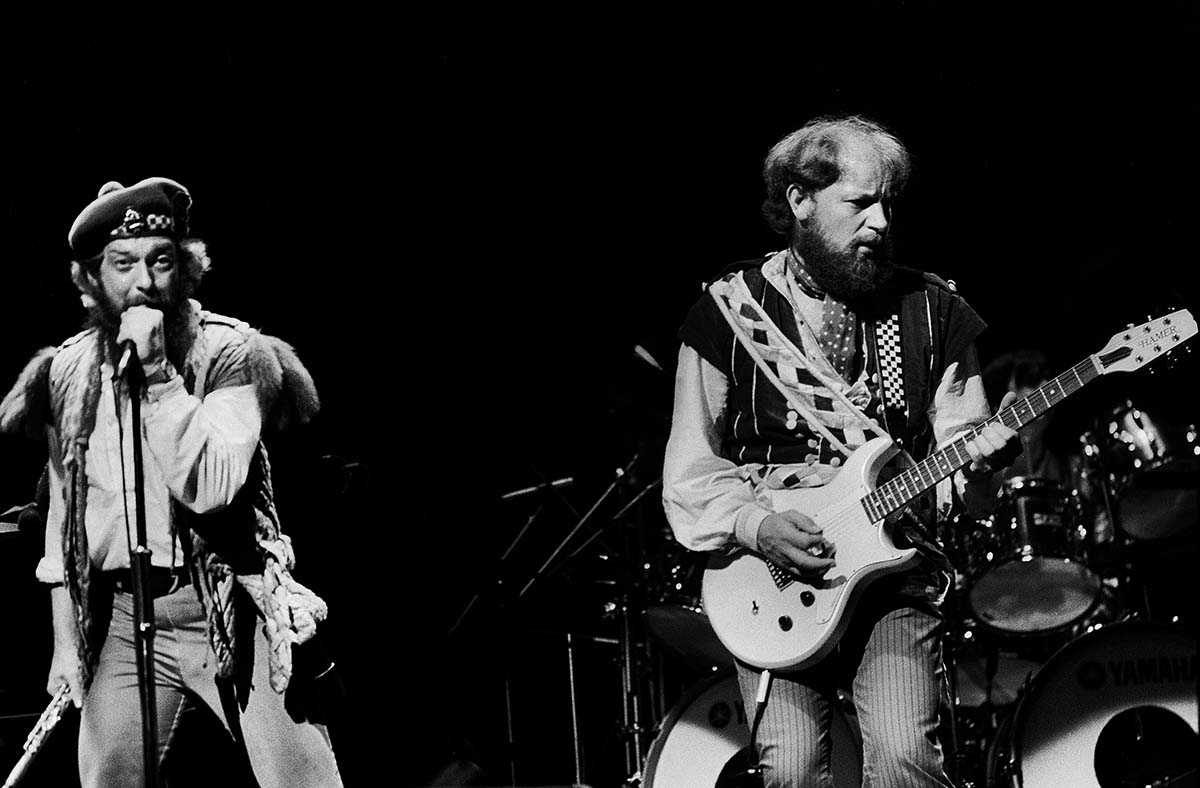

Are there any songs that are particularly challenging to reproduce live?

If something is really difficult to achieve, that really gets my blood pumping. I love a challenge. I’m looking at “My God” at the moment and thinking of ways around the acoustic guitar intro, which we won’t play. I’m going to do something really cool there, which will be different.

The flute solo won’t be there, but I found a piece of music that we’ll play instead. It’s called "Palladio," by Karl Jenkins. It’s a great driven, dynamic piece of music. That will replace the flute solo. A lot of flute solos and keyboard parts from Tull albums have been changed into guitar parts when I do them live now.

I think it is a valid way of reproducing the songs. I don’t think you have to keep things exactly the same as the record. In my mind, a guitar can replace anything – a piano, violin, saxophone or whatever.

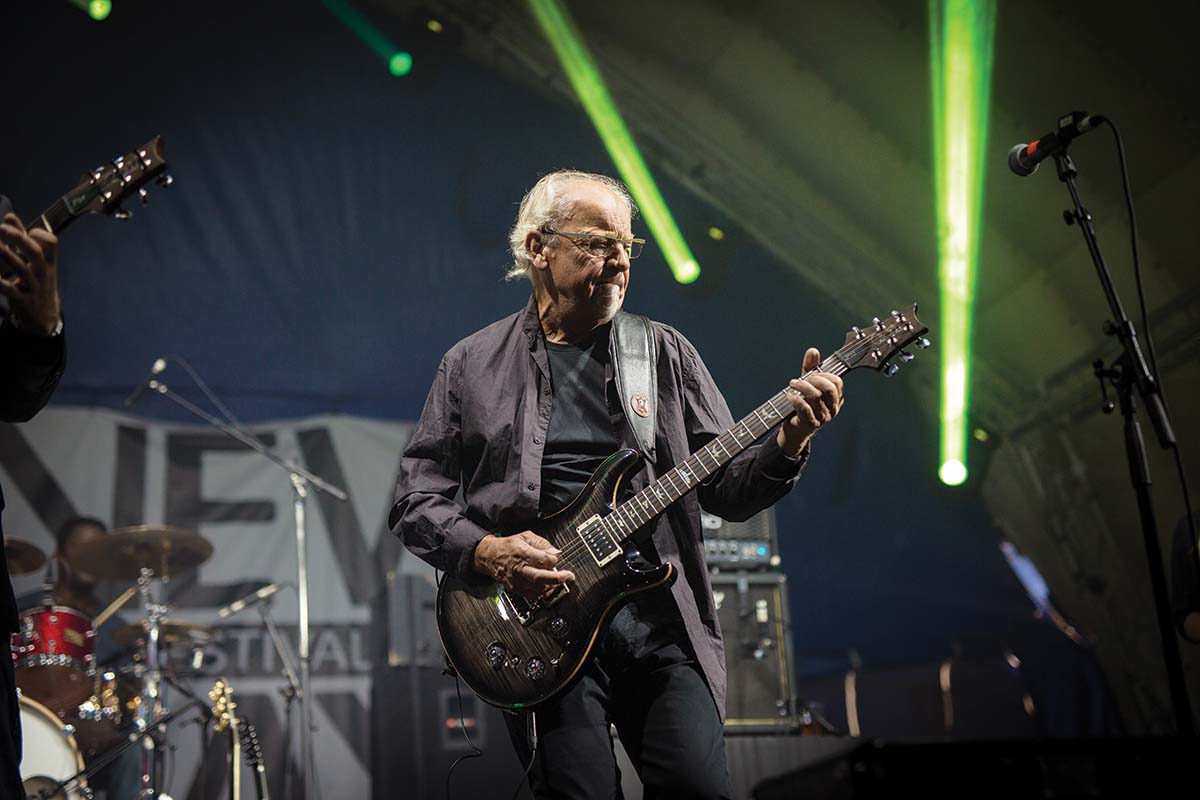

I suspect most Guitar Player readers would agree with you there. When you get back on tour with the album, will you be using your current setup? Any temptation to go full retro gear-wise?

[laughs] I don’t own any of the gear to go retro. I’ll be using my PRS guitars and Soldano amplifiers. I like a variety of instruments, but on the road you need the tools to be 100 percent reliable.

I always use the PRS guitars on the road, but I will play a variety of different guitars at home. I’ve got old Gibsons and Fenders, but my favorite guitar is a Parker Fly. I think it is the most underrated instrument on the planet. It is superb. I don’t know why it never caught on, as they are so way ahead of their time. They really do everything.

It’s not my job to qualify it, of course. I stand by all the Tull albums, and I think it’s a disservice to say that one is better than another

I think perhaps the problem was that guitarists are essentially conservative by nature when it comes to the guitar itself, and the majority of popular guitars still look pretty much the way they did in the ’50s.

Yeah, it doesn’t conform; it’s not a Les Paul or a Strat. It’s my go-to instrument. Plus, you can play it for three hours and you don’t get a bad back. [laughs]

Looking back at Aqualung, how do you think it stands up in the Tull catalog?

Well, I stand by it. It’s not my job to qualify it, of course. I stand by all the Tull albums, and I think it’s a disservice to say that one is better than another. I have favorite Tull tracks, but they’re scattered all over the different albums. I think there is so much good stuff in our catalog. We never did anything with less than total commitment.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.