All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Steve Howe has no idea where the term progressive rock came from, but he makes one thing clear: It certainly didn’t start with him. “I never called us ‘progressive rock’ or ‘prog-rock,’” he says. “As I recall, when I first joined Yes, we all used to call our music different things.

"There was ‘orchestral rock’ and ‘cinemagraphic rock.’ We never argued about it, but there were a lot of names and terms being tossed about.” So what term did he use to describe Yes’s music?

Howe laughs. “I often called it ‘soft rock,’” he says. “I thought what I wrote was a sort of soft rock, but the phrase didn’t catch on, at least not with what we were doing. But progressive rock? Where that got started, I don’t know. I think it might have come after the fact.”

Howe had already achieved a fair amount of notoriety as a guitarist by the time he joined Yes in 1970. Beginning his career in 1964 at age 17 with the London-based R&B group the Syndicats, he then joined the soul-and-covers band the In-Crowd, which soon transformed into a psychedelic outfit called Tomorrow.

After Tomorrow broke up in 1967, he played on a few sessions and recorded a couple of tracks with a pre-Faces Ronnie Wood before hooking up briefly with a rock trio called Bodast.

When that band’s record deal fell through, Howe plotted his next moves. He auditioned with Keith Emerson’s band the Nice but didn’t think they were the right fit for one another.

He bailed on a try-out for Jethro Tull when he discovered they weren’t open to his songwriting. And an audition with the Atomic Rooster (which featured Emerson’s future bandmate Carl Palmer on drums) didn’t result in a love match. “I had done my share of playing around and had gained a lot of experience,” he says, “but I was looking for the right kind of band that allowed me to do whatever the hell I wanted.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What Howe was looking for was a musical outlet for his burgeoning interest in songwriting, but also one in which he could apply all the facets of his guitar-playing vocabulary, which by now included jazz, rock, classical, and flamenco. And such a situation opened up when Yes founding guitarist Peter Banks left the band in April 1970.

Joining Yes – which then included singer Jon Anderson, bassist Chris Squire, drummer Bill Bruford, and keyboardist Tony Kaye – gave Howe the perfect opportunity to spread his creative wings.

I had been in bands that were pretty good, but suddenly I was with people who were world-class

“I was ready for it,” he says. “Right away, I could feel that this was a band that was head and shoulders with me, and vice versa. I had been in bands that were pretty good, but suddenly I was with people who were world-class. I admired each member for his particular talent.

“I thought this was like an orchestrated band. We were going to write parts; we were going to write songs with great lyrics and music that really went somewhere. We were going to throw this whole thing out to the world. That was the plan.”

By then, Yes had released two admirable but rather disjointed albums – their eponymous 1969 debut and 1970’s Time and a Word – that failed to chart in the U.S. and barely made a dent in their homeland.

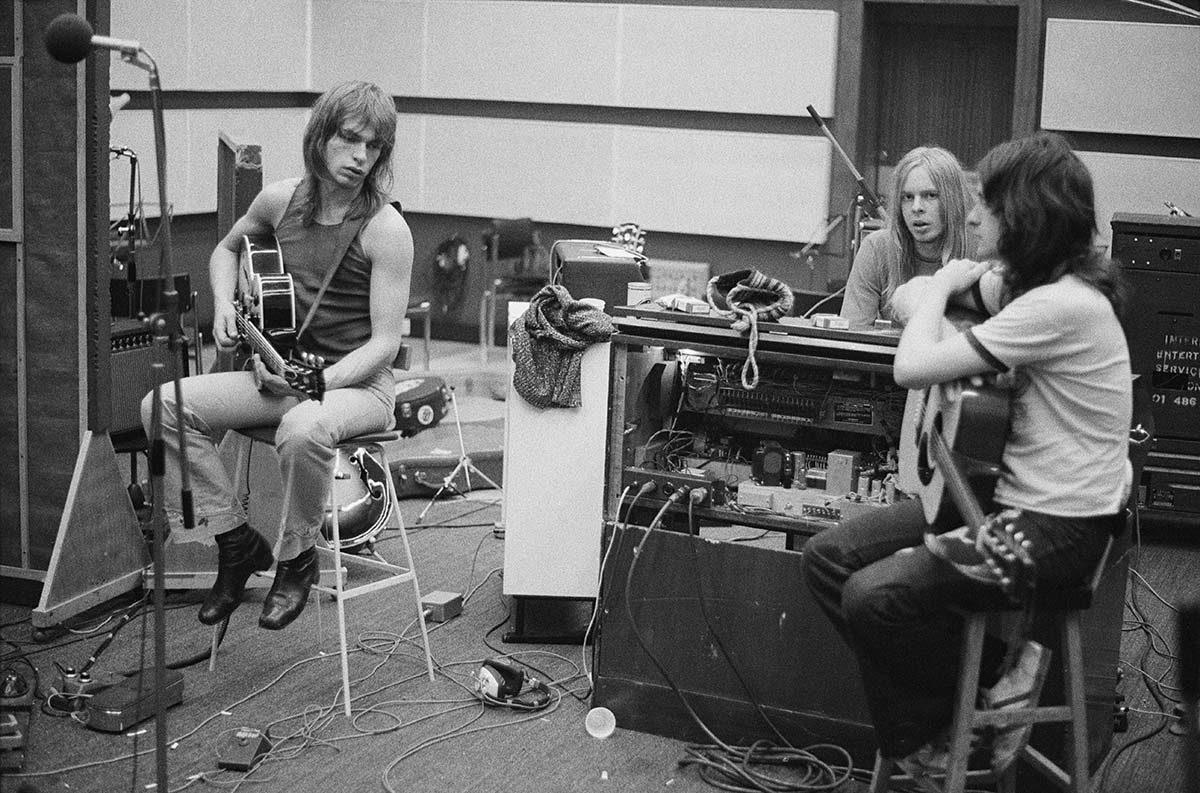

Howe’s transcendent skills as a player and songwriter ignited a creative fire in the group, and they kicked off 1971 in grand style, starting with The Yes Album. The group dispensed with the reworkings of cover tunes that had bogged down their earlier efforts and focused on original material that allowed them to carve out a new identity.

The album was brimming with expansive, energetic, and hook-filled rockers like “Yours Is No Disgrace,” “Starship Trooper,” and “I’ve Seen All Good People,” each of which made full use of Howe’s wide-ranging repertoire of guitar styles. The Yes Album turned the heads of critics and record buyers alike, hitting number four in the U.K. and cracking the U.S. Top 40.

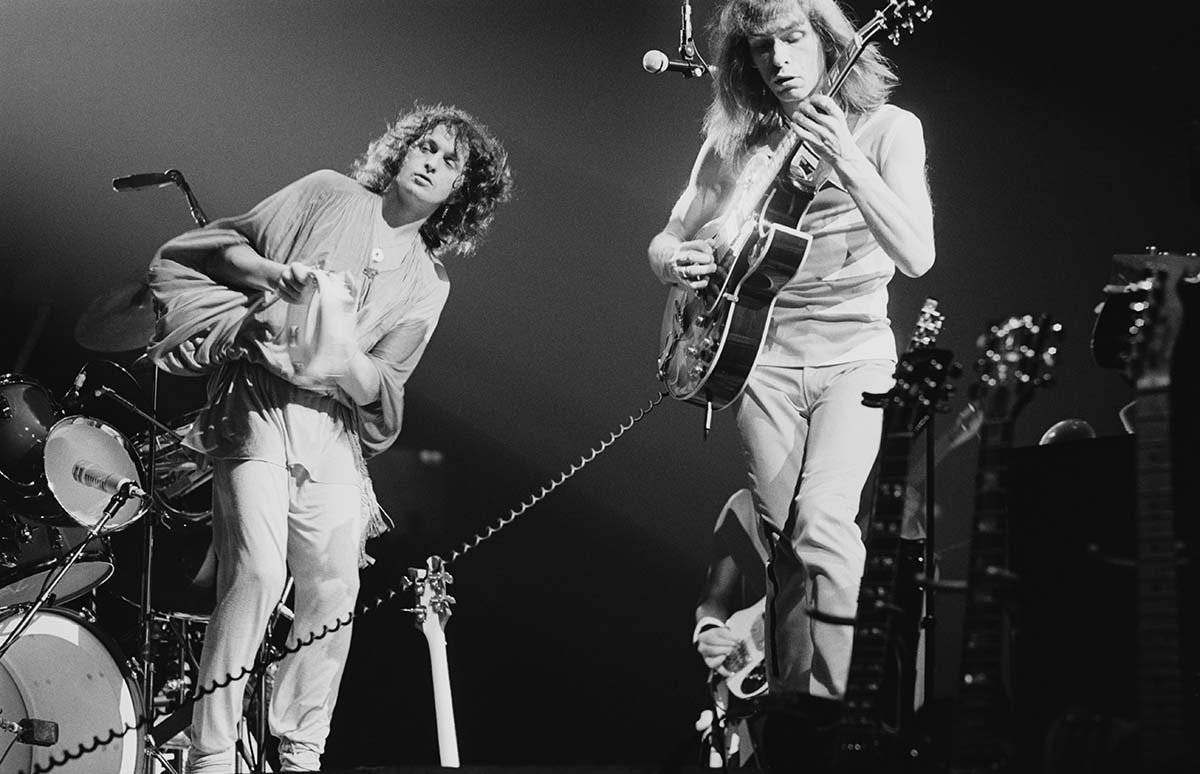

By the end of 1971, Yes were firing on all cylinders and they delivered the second half of their one-two punch with Fragile. A superlative sustained musical statement, it saw the band framing Anderson’s fanciful, sci-fi-laced themes with wildly inventive and hyper-aggressive arrangements.

'Fragile' is a lovely album to listen to because it’s a real recording. The whole band had a chance to do their own thing on it

Egged on by the turbocharged rhythm section of Bruford and Squire, Howe and the group’s wily new keyboard whiz, Rick Wakeman (who replaced Kaye just prior to the album’s sessions), engaged in electric games of one-upmanship that revealed how they were actually two sides of the same creative mind.

It didn’t hurt that Yes were sitting on a sublime collection of melodic gems – most notably “Roundabout” and “Long Distance Runaround” – that hit radio playlists with deadly aim. Within months of its release, Fragile became the breakthrough the band had long sought, reaching Number Seven in the U.K. and going to Number Two in the U.S.

But success wasn’t without its compromises. Howe recalls how, after the band delivered Fragile to its U.S. label, Atlantic Records, and laid down the edict to promote it at all costs, the radio department responded with a three-and-a-half-minute single edit of the nearly eight-and-a-half-minute album version of “Roundabout.”

“We did react with some horror to that at first,” he says. “But on the other hand, we were sensible enough to realize that it was simply an advert to an almost 10-minute song that wasn’t going to be played on every station. There’s always a rub.”

I think 'Fragile' is the one where we sounded like us. It’s sort of like Wes Montgomery – he made a few records and then suddenly he sounded like Wes Montgomery

On their own, both The Yes Album and Fragile were enough to signify that a radical shift was afoot in some quarters of British rock. Combined with the efforts of contemporaries like King Crimson and ELP, they helped shape a movement.

Asked if he has a strong preference between the two albums, Howe hesitates. “That’s a tricky one,” he says. “I mean, they’re such different records.” But after a second, he offers his definitive assessment: “I think Fragile is the one where we sounded like us. It’s sort of like Wes Montgomery – he made a few records and then suddenly he sounded like Wes Montgomery.

“For me, Yes were pretty good on The Yes Album; we had a quirky sound. But I think the production, the ideas, and the tightness were exceedingly good on Fragile. It’s a lovely album to listen to because it’s a real recording. The whole band had a chance to do their own thing on it.”

Before joining Yes, you were sniffing around other bands. What made Yes appealing to you over other groups?

Well, they were pretty intelligent and clever people. They laughed a lot. There was a good time to be had. I don’t think you can dismiss the value of human communication and respect. So that made the enterprise very desirable to me and made me think, I should really get behind this.

I listened to the way Bill Bruford played drums – he could do jazz and rock, and really weird-out. I used to love it when he’d say, “Tonight I’m going to play all my drum breaks differently.” Although sometimes I didn’t. I’d be like, “No, Bill, please don’t.” And he’d say, “No, I’m going to.” And he did. [laughs] That’s the kind of band Yes were.

They definitely auditioned me... It was just like any other audition, really. I plugged in and we started playing, and I thought, These guys are good. I guess they thought the same of me

Did you audition for Yes, or did they take you sight unseen?

Oh, no. They definitely auditioned me. Chris called me and said that he and Jon had seen me play, and they said I was pretty good. They asked me if I wanted to get together and play, and I said sure. I took a bus to Putney, where the manager lived, and they were set up in the basement.

It was just like any other audition, really. I plugged in and we started playing, and I thought, These guys are good. I guess they thought the same of me. We played a bit and they saw I could do stuff – I could improvise. I thought, Yeah, take me. There was a fair bit of enthusiasm in the room. Bill had reservations because he thought I was too much of a hippie. I loved that. [laughs]

Did the fact that you could sing also work in your favor?

It didn’t really. I was just playing guitar at the time, but Yes did give me the platform to sing with Chris. I would often sing the third parts – the low parts. I learned very quickly that I could sing, which was incredible.

All the big bands had lots of singers: The Beach Boys, the Beatles. Everybody sang. You had to. So although I hadn’t really engaged with it in the ’60s, I was certainly interested in doing it with Yes, and it became a full-on commitment.

Before you joined, Yes did a fair amount of cover tunes on their records. That stopped with The Yes Album.

It did. I would like to take credit for it, but I think the band were headed that way anyway. At one point, I think I said, “I don’t know about playing cover tunes,” and they said, “Don’t worry. We’re not planning on that.” They had done it already.

I had just come out of bands that wrote their own material, so my way of thinking was, Okay, let’s write! The other thing I liked about singing was it allowed me to present songs to people. I could sing to somebody and say, “This is the song.”

Eddy Offord had a bit of a bossy side, but he knew stuff. He knew which knob to turn to make you sound awesome

You played a bunch of live shows with the band before recording The Yes Album. Did it take a while for you to get used to large rooms?

Not particularly. I’ve been playing onstage since I was 15. I joined the In-Crowd in the ’60s and they had a hit record, so I was used to playing all sorts of places with girls screaming at us, which was ridiculous. We kept at it a while – played big shows with Jimi Hendrix and all that. Playing with Yes was very inspiring musically right away. We came across well. I’d say we knocked some people out.

Producer Eddy Offord became the progressive producer du jour, dividing his time between Yes and ELP. What was he like to work with?

Oh, he was terrific. On those first three albums I did with him, it was all plus, plus, plus. He had a bit of a bossy side, but he knew stuff. He knew which knob to turn to make you sound awesome. That’s a big part of producing, isn’t it? He was great on tape machines. I learned a lot from him. He was totally on it.

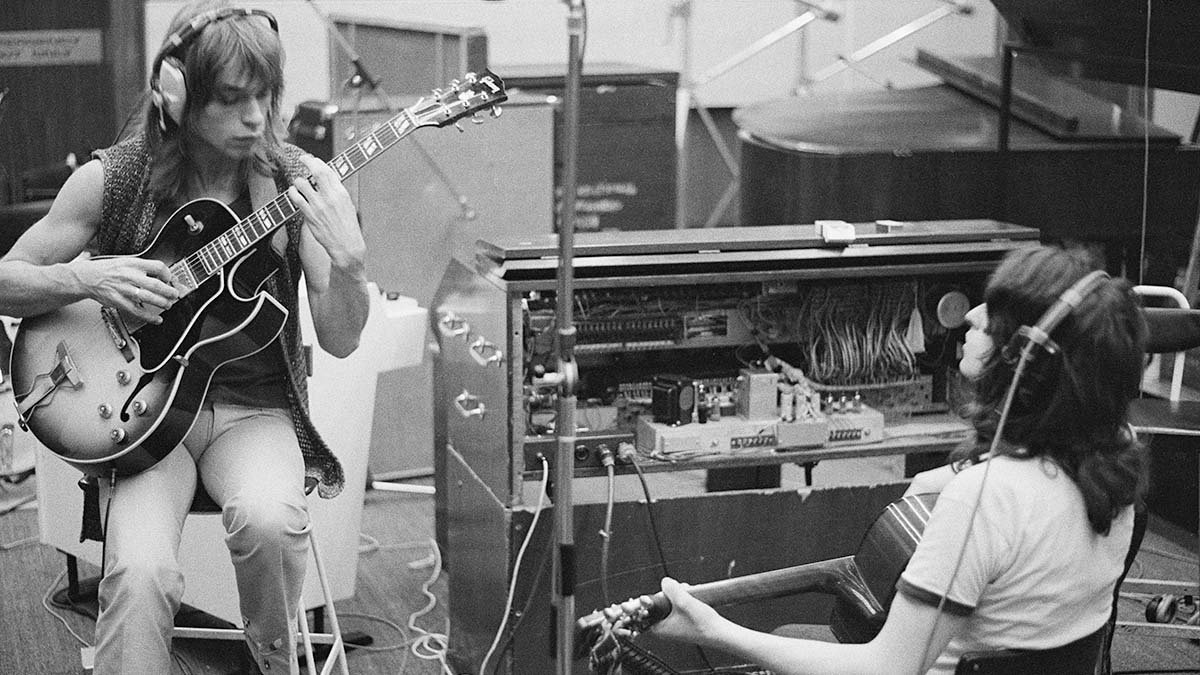

You guys and ELP also shared the same recording spot, Advision Studios. Was it a comfortable place to work?

Yeah, but it was very simple. It was in the West End of London, like a few other great studios. You went in, and there was a studio downstairs – that’s where we mixed things like Yessongs. But the main studio was a great room at the time. Eddy liked to work there, and the place had a bunch of people who were very nice.

It was a kind of trendy studio. It wasn’t popular in the kind of EMI sense, but there were certain people who liked it. You were kind of isolated in Advision. You’d go to other studios and there’d be people milling about; it was hard to concentrate with all that going on. At Advision, you could focus on what you were doing.

This was especially important on The Yes Album because it wasn’t recorded in any sort of block. We didn’t do three straight weeks of sessions. It was recorded in small chunks of time. Three hours here, half a day there. Sometimes we got a whole day.

We’d have to go back to the studio and set everything up again, and then we’d go off and do some shows. In a sense, it was beneficial as we were a new band in a way. It was certainly a new band for me. We were learning how to write and make records of our own material.

Your solo guitar track “Clap” was recorded live at the Lyceum Theatre in London. Did you have that song already written and in your back pocket before joining Yes?

Well, yes. I actually wrote it on the 4th of August, 1969, on the night that my first son was born. So he was born, and six months later I’m starting to get to know who Yes are – I knew I was going to play with them. So we were writing The Yes Album, and it was one night in this old farmhouse and I said to them – or maybe it was Bill Bruford – I said, “I’ve got this guitar solo. What do you think?”

Chet was the biggest influence on me. I just wrote “Clap” out of admiration for him

I played it to him, and he said, “That’s terrific. Let’s stick it on the album.” And then they all said, “Let’s stick it on the album.” And I went, “Okay, that’s nice.” I was very impressed that I got the opening to do that, and I forever thank them for that. But, of course, Jon said on the recording, “Steve’s gonna play a tune called ‘The Clap.’” And it became “The Clap,” even on the record at first, and that was a mistake.

I wasn’t really conscious of its meaning at first, and then I discovered that it had this wrong connotation. I was like, “Hang on here!” Eventually, I got Warner Brothers to officially change it to “Clap,” but it was too late. It had already gotten out there.

But that piece is the quintessential coming together of all my love for Chet Atkins. There was basically him and Merle Travis, along with other great guitarists who inspired me along the way. But Chet was the biggest influence on me. I just wrote that out of admiration for him, really. The opportunity came along where I could write that as my first-ever solo guitar instrumental, and it’s a pretty hard one to beat.

You used backward flanging on the “Wurm” electric outro section in “Starship Trooper.” Was that kind of studio trickery new to you at the time, or had you already been experimenting with effects?

It was sort of new. We recorded my guitars completely clean through a [Fender] Dual Showman. It was just a plain-old clean sound, but we’d planned on using some of the effects that were coming out. There was the Eventide and the Bell flangers. I don’t think we had an Eventide yet, so we used the Bell.

That was an English flanger, and it got a great sound. It was fun to play with that. So we recorded the “Wurm” bit, ran it down clean, and then Eddy and I got down to things. Sometimes we were the first and last people in the studio, mucking about with things. We got a nice sound on that. It sweeps you away.

Some of my classic solos are actually a combination of different riffs I’d been playing... that was my approach at the beginning

Your solo in “I’ve Seen All Good People” is beautifully composed. Are there any parts to it that were improvised?

Well, to an extent, some of my classic solos are actually a combination of different riffs I’d been playing. On that solo, a few bars into it, there’s an unusual use of chromatics, where it goes up but then goes down to a lower string and goes up again; and then it goes down to a lower string and goes up again.

Those were things I just had lying around, so basically that was my approach at the beginning. That arrangement, the way I had Chris and Bill kind of punctuating and signposting everything in the solo – it worked out well. I love that solo to bits. I often try and play it note for note, but I can’t always match it 100 percent. It’s sort of a blueprint.

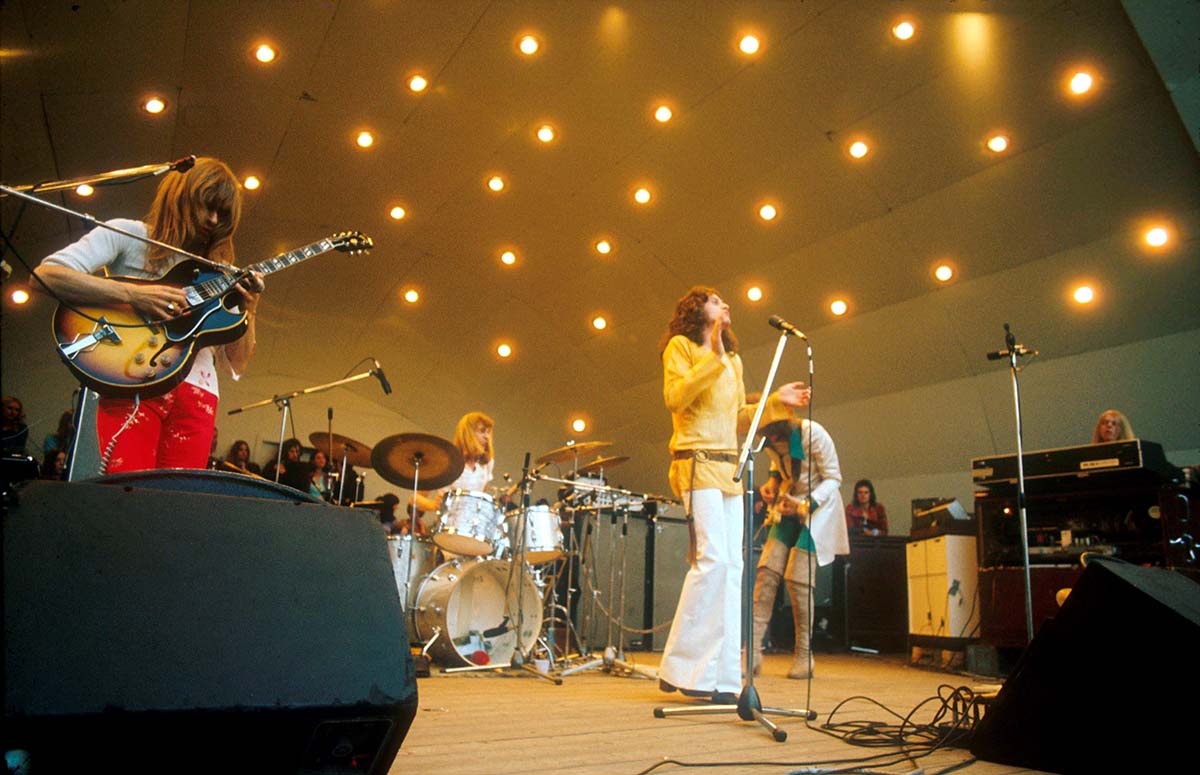

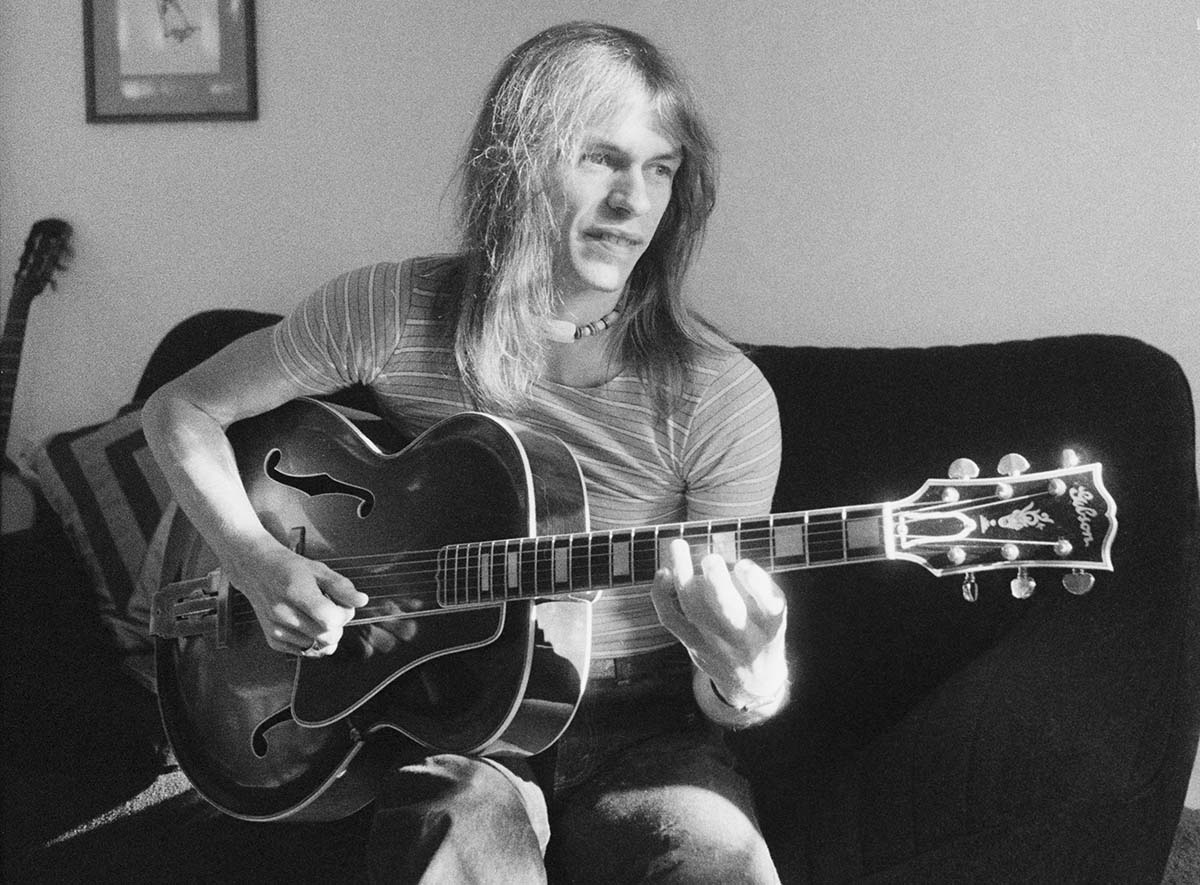

Your Gibson ES-175D was the bedrock of your sound. Did people think that was a strange guitar for a rock player at the time? You were about the only guy playing one outside of jazz.

A lot of people looked at me as if I were weird for playing a full-body jazz guitar, but I’d seen guitarists I’d quite admired play it. Judd Proctor – he was one of these professional players you’d see backing people up. I saw him with a 175 on TV, and I thought, Oh, my God! That’s what I want. I picked up a Gibson catalog and decided the 175 was the guitar for me.

I wasn’t going to get an L-5. Too expensive. Didn’t want a Les Paul. But it almost went wrong. I had unwisely been drinking beer while playing the 175, and I dropped it, slightly damaging the input jack. I took it to the shop to have it repaired, and while I was there I saw a sunburst Les Paul Standard.

I thought, I don’t know… It looks kind of cool. I took it home, played it, and I thought, Wow, that’s it with the 175. I’m gonna get one of these! A week later, I went back to the shop, and the 175 came out from the back. I opened up the case and took a look at it and thought, I was wrong. I’m not gonna compromise. So it was back to the 175. It’s always been a great guitar.

It’s funny. We were adaptable to places like the Whisky. We could streamline

You guys did a pretty extensive North American tour for The Yes Album. You even played the Whisky A Go Go in L.A. It’s hard to picture Yes playing there.

It is hard, isn’t it? I remember my crew guy fell asleep in this little cubbyhole by me while we were playing. He had obviously been up all night doing something he shouldn’t have. It’s funny. We were adaptable to places like the Whisky. We could streamline.

Moving our gear around could be a chore. Somehow we managed to get these Dual Showman amps up escalators in airports and onto planes. The West Coast was a pretty big deal for us. We’d been to the East Coast. We’d seen downtown New York and had been on some of the streets. L.A. seemed like a paradise. After a while, it was someplace to look forward to – the beach and all that.

Right at the end of that tour, Tony Kaye left the band and Rick Wakeman joined.

That’s right. It’s always the same in Yes – necessity comes along. Tony’s reluctance to be flamboyant on multi-keyboards was really apparent, and he wasn’t going to budge from being who he was. It’s how he played, and he wasn’t comfortable with so much gear. But we were already thinking about that stuff, so that was part of it.

It’s a shame that Tony didn’t stay with us and develop his thing like Rick was able to. We’d seen Rick play with the Strawbs, and we thought he was great. He had a funny way of joining, though. He wasn’t always in attendance at our recording sessions for Fragile.

'Fragile' was recorded more as a piece of production as opposed to a band going in and playing live

He was a busy session guy, so he’d pop in and say, “I’m free at three tomorrow.” And we’d be like, “Oh, okay. Drop in then. Do that.” Which basically allowed the rest of us to get tracks sorted, so he’d come in and play on them. We didn’t mind.

There were some tracks we needed Rick for because we had to sort out the guide parts of the keyboard, so all the members had to be present; and sometimes four were enough.

There were tracks that had parts where I wasn’t playing, like on “South Side of the Sky,” so I could sit there and go, “Oh, yeah. That sounds nice.” There was a good sense of teamwork.

Fragile was recorded more as a piece of production as opposed to a band going in and playing live. We constructed tempo, drum parts, guitar, keyboard – how many of these, when the verse came, when the chorus came, when this happened. It was a beautiful thing. We benefited from having that production mindset at that point.

When Rick joined, did he mention that he was going to wear capes onstage?

[laughs] No! No, he left that bit out. But that’s what was great about Yes – you could wear whatever the hell you liked. You had to look fairly smart and presentable, like you’d made an effort. A lot of things got played out, and then we were onto the next thing. On Relayer, when Rick wasn’t there, I had a cape, but it was a really short one.

We did dress up a little bit. Chris made a lot of effort. He had some boots that we used to call the “poodle boots.” They would come up right above his knee. He was a big, tall, slim guy, and he’d hoof around very agilely most of the time. It was fun. I’ve always felt that getting dressed for the stage was an important thing. I never went on in the same clothes I wore all day.

We did dress up a little bit. Chris made a lot of effort. He had some boots that we used to call the “poodle boots.” They would come up right above his knee

On “Roundabout,” did you have the acoustic intro written when you came up with the main riff?

Yeah, that came along with what Jon and I wrote together. It was something that was there, because it led into the verse structure, and almost the chorus structure too. The chorus is really like a major version of the minor verses.

I’d always had a thing about intros. I guess I’d played a lot of them in the past, and now I’m quite fanatical about intros and endings. It’s like, if the song doesn’t start out like something, then it’s not going to go very far, is it?

The intro to “Roundabout” is a classic. It’s got three different ideas going, so I quite like it. Fragile was that kind of album. It wasn’t like a live record where we went in and played and people strummed. All of a sudden, we didn’t like strumming. It was like, “Why has anybody got to strum? Play notes! Play a part, a riff. Play a line, play a theme. Do anything but strum.”

I just loathed the idea that Yes would have too many songs we just strummed on. Of course, there were songs we did that, but they were done in a certain texture, where it wasn’t just a cop-out for not thinking of something better to play.

Was “Roundabout” a particularly tough track to get right?

We spent a lot of time on it. We did everything in a lot of sections. We’d choose from different takes. We’d have half a song done, then we’d play back the second half and take over. That could be a risky thing, but Eddy was into it. There was a lot of editing, but it was all quite exciting.

What we were making was high-class new music. We didn’t know you could chop down 10 minutes and have a hit, and we didn’t want to do that

How composed was the guitar solo?

On certain lines, there was some improv, but some of those main lines were already there. You’ve got to have them thought out to give the solo value. And Rick and I doubled on them, of course. We both had spots where we could rock it up or jam it out, whatever it was.

There were takes where I put my head in and improvised, but certainly there was a degree of things that I played often, where I kind of pulled off on the G string. That was a simple thing I used in different places.

For the acoustic parts, you used a Martin 00-18, is that right?

That’s right – the first one I’d bought. It’s from 1953, and I’d bought it in 1968. I’d seen Paul Simon with a guitar. I’m not sure what it was, but I thought it was a 00-18. I wanted a Martin, and the minute I got in a shop and played it, I realized that the fingerboard was everything I was looking for.

Not only that, but the sound was just perfect. Strangely enough, we tried it in the studio and it sounded too dead, so I got it in a corridor outside the studio, set the mics up, and it sounded great. We liked to do stuff like that. “And You and I” was recorded in a booth. I played Chris’s 12-string Guild acoustic.

“Roundabout” became a massive hit. When you were listening back to it, did you think you had something really special?

Well, I mean, we weren’t really making hits. What we were making was high-class new music. We didn’t know you could chop down 10 minutes and have a hit, and we didn’t want to do that. We didn’t dirty our hands with that idea.

When we finished The Yes Album and I listened to it, I didn’t really know how we’d go over, whether we were too quirky and British nerdy. But when we finished Fragile, I went, “Oh, my God. This is fantastic. I’ve always wanted to be in a band that sounded like this.”

“Long Distance Runaround” has many cool guitar parts. But how did the heavily delayed bits you play at the end come about?

Do you mean when the band stops and I play?

As far as “Mood for a Day,” the way I play it – or learned to play it – over the last 25 years is far superior to what I recorded

Yes, that part.

That was done with some sort of Echoplex. I wouldn’t think it was a [Watkins] Copicat by then. I always had delays around; I had a few of them. You had to really play with the delay. You had to be able to hear the delays to make it worthwhile.

I think I’m fairly uncomfortable with that little bit, actually. It was a great opportunity, but I would definitely learn how to do it better now. That was a real opportunity to do a kind of crossfade between that and “The Fish.”

You have another solo-guitar spot on the record, “Mood for a Day.” What absolutely gorgeous flamenco playing!

Thanks for saying that. I’ve played the song many times since recording it, and I think I was pretty heavy handed back then. I don’t mean reckless, but more heavy going.

That did give it a really strong flamenco feel, which I don’t relate to now. I think guitar should sound beautiful. Period. As far as “Mood for a Day,” the way I play it – or learned to play it – over the last 25 years is far superior to what I recorded.

Did you use your ES-175 on most of Fragile?

Not mainly – only on “Heart of the Sunrise.” On the rest of the album, it’s a Gibson ES-5 Switchmaster. I played that on “Roundabout,” “South Side of the Sky,” and “Long Distance Runaround.” I think it’s on “Five Per Cent for Nothing.”

The Switchmaster was an even bigger jazz guitar than the 175, and I was quite high on it at the time. But it didn’t work for “Heart of the Sunrise,” so I was back on the 175. My amp was still the same, as far as I remember – the Dual Showman.

I didn’t have a car, didn’t own a house. I was just getting by, paying the bills and living... All of the sudden you’re playing the Forum, Madison Square Garden

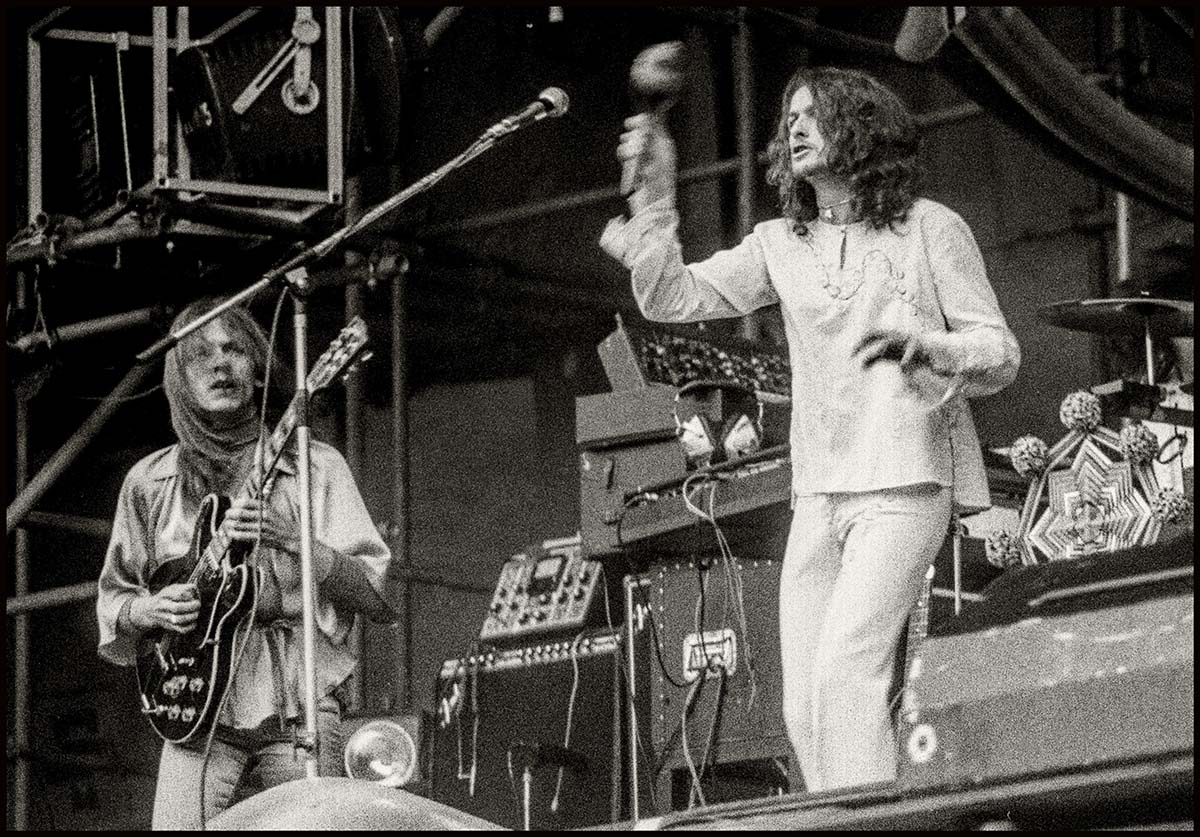

When the album was released, it seemed as if everything lined up for you guys – radio play, record sales, sold-out shows. How different was the reality of success versus what you had imagined it would be?

I’d describe it as two sides of a door. On one side I had my private life, which at that point hadn’t changed a great deal. I didn’t have a car, didn’t own a house. I was just getting by, paying the bills and living. But it was all rather beautiful, really. But on the other side of the door, there was enormous success, where everybody’s like, “Oh, there’s a limo for you,” or, “These people wanna meet you.”

All of the sudden you’re playing the Forum, Madison Square Garden – it’s all kind of happening. But fortunately, I was able to maintain my sameness and be a private person. I still do it. I get on with my life. I’ve got my problems, I’ve got my joys, I’ve got my miseries. I never got hooked into ego.

Sometimes I walk around and people are like, “Hey, isn’t he…?” You know, they can tell I’m somebody they’ve seen somewhere. Most of the time, though, I get away with a great deal of freedom.

One funny thing about the Fragile tour: Before you guys hit the big places, you did four more dates at the Whisky.

I know! What were we thinking? [laughs] You know, there was a notoriety to the place. Everybody and their uncle played there, so we didn’t want to miss out on it. You played there because it was the happening place.

- Yes's Fragile (Expanded and Remastered) is available now on Elektra.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.