The Gospel According to Taj Mahal: Resonations From Africa to America

In part one of Guitar Player's epic interview with Mahal, the master songwriter unpacks his love of acoustic guitar and the resonator, and musical influences near and far.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

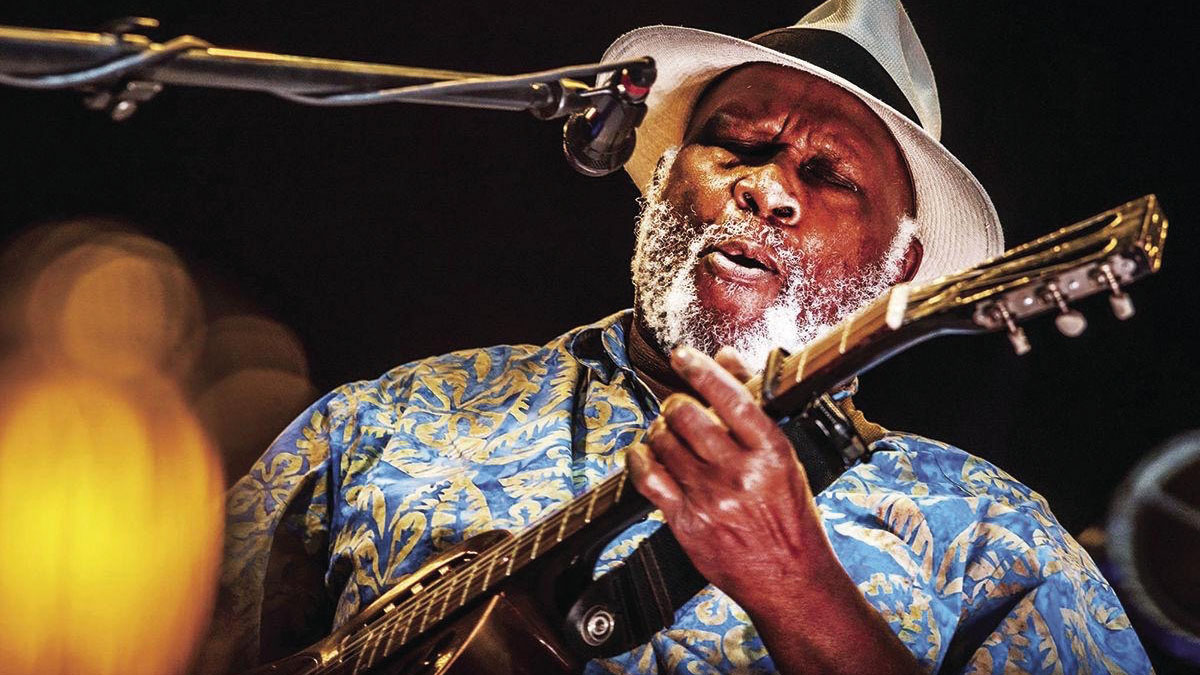

"Acoustic music is my roots, my chapel,” says Taj Mahal, the international treasure that adopted his stage name from one of the most iconic temples on the third stone from the sun. The maestro graciously invited Guitar Player to his home, where he took us to school and to church, delivering an unforgettable sermon on the sanctity of music.

Approaching the Taj Mahal residence in Berkeley, California, a Regal resonator tone accompanied by wind chimes emanates from the front porch, which is covered in bountiful springtime flora.

The sound is timeless, the style familiar, yet exotic. I’m accompanied by Jules Leyhe, a bottleneck whiz who provided the Allman-centric lesson in GP’s July 2018 slide issue and is currently my guitar partner in my band, Spirit Hustler.

Jules has been helping out the legendary roots musician during the pandemic, and he set up what turned out to be one of the most informal and informative interview experiences one can imagine.

Upon his arrival, Leyhe recognizes that Mahal is fingerpicking “Mkutano,” which he confirms has an East African influence. Taj proceeds to detail how it came from his experience playing in Zanzibar with a large ensemble that was “like an Arab orchestra,” and is documented on the 2005 album Mkutano Meets the Culture Musical Club of Zanzibar. So began our trip through time and space with one of the most worldly players walking the earth.

As it turns out, he’s also one of the most unpretentious and downright hilarious mother-pluckers on the planet.

How is the Piedmont blues fingerstyle you picked up as a young man in North Carolina connected to African roots?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Fingerpicking in general goes back to the West African kora. It’s got 21 strings: 10 on one side of the neck and 11 on the other. You pluck with the thumb and fingers of both hands on either side. If you pluck a resonator guitar and articulate the notes just right by cutting off sustain with palm muting, it produces a somewhat similar sound.

You’ve played many different guitars over the years, but it seems you have a special love for the resonator.

Yeah, for a while it was resonators all the time. It took me a while to get to it, but once I got to the resonator, you never saw me without one. The electric guitar was still in front of me. Ground zero for me is acoustic guitar. When I started out, the guitar was an archtop with f-holes.

What I saw was cowboy country players with round-hole guitars, whereas jazz and blues players had f-hole guitars. I was mostly looking at guys like Oscar Moore [Nat King Cole Trio] and Charlie Christian. It wasn’t until the ’60s that I saw southern black musicians playing round-hole guitars.

I’ve watched so many players give up that space, and then they can’t get back there because all they’re doing is playing electric licks on an acoustic guitar

I liked Chuck Berry when he came around, and even he was playing a big guitar with f-holes. The other guitars sounded twangy. Acoustic music is my space, and I always told guitar players about the importance of having one.

I remember being in Spain in 1970. I met a monster classical/flamenco player, and he asked me if he should switch to the electric guitar. I told him, “No matter what you do, don’t ever do that! Here you’ve got a real space in the world.”

I’ve watched so many players give up that space, and then they can’t get back there because all they’re doing is playing electric licks on an acoustic guitar. Buddy Guy started out on a box guitar, and every once in a while he’ll go back and play one, but then he sounds the same as on an electric guitar.

You sound different depending on the instrument. How’d you get into the resonator?

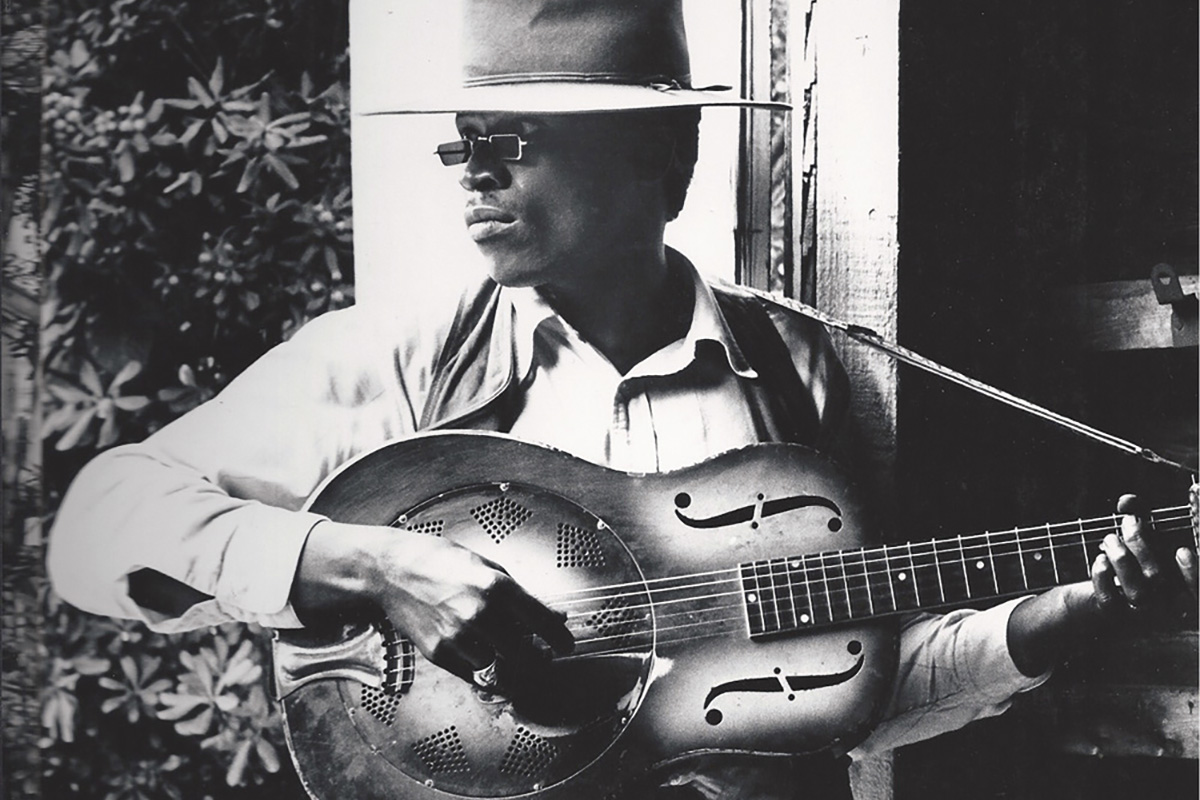

Way back when I first heard the resonator guitar, I didn’t realize what it was. I only knew it was something different. Then, in the ’60s, I started seeing old pictures of all these guys, but it was Sister Rosetta Tharpe that played a sunburst National, similar to the one I came to play.

I came to realize that on a trip home sometime in the late ’60s. I was sitting on the front porch playing a Duolian when my mother came out from the kitchen drying her hands on her apron, saying, “That sounds just like the guitar that Sister Rosetta Tharpe played.” Then she sat down next to me.

We did a version of [Leadbelly’s] “Take This Hammer” and she nearly stomped a hole in the front porch! That’s when I started looking for pictures of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and I found a great one of her standing in a long gospel dress with that National guitar in her hands.

I got a recording of her playing it. I didn’t know what tuning she used, but on “Up Above My Head,” with Andy Kirk’s ensemble and a big gospel choir behind her, she strums a chord at the end, and she’s obviously in open D tuning, what they used to call “Delta tuning.”

How did you come by your Duolian?

I got mine from a guy who couldn’t play very well, and then he took an acid trip while playing and realized that he really couldn’t play that well. [laughs] The only guy he knew that he thought played well was me, so he gifted me that instrument. Years later, he came back for it, and I was like, “Here ya go.” I just gave it back.

I wasn’t going to argue with him. I said, “With all the mojo that’s in there, you’ll be lucky if you can play it. It ain’t gonna play for you.” And it never did. He never had a career with the guitar, but I appreciated it very much because that guitar is on The Natch’l Blues and Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home [released in 1968 and 1969, respectively].

So that’s the sound right at the beginning of “Corrina”?

Yeah, that’s the Duolian. The tuning is drop D, but I’m playing in A. I was teaching the tunes I’d worked on arranging to three guys from Oklahoma. Two of them were Anglo Americans with English and Welsh backgrounds, and Jesse Ed Davis was a Comanche Indian. I’d show him the arrangement, and he’d weave his stuff around what I did.

Keb’ Mo’ told me that The Natch’l Blues changed him around all over the place. He said that he had it in his car for years until somebody stole the stereo out of the dashboard

He’d put his flatpick in the cleft of his chin, and give you a 20,000-mile stare. He’d disappear to somewhere, and then he’d come back and say, “Chuck [drummer Chuck Blackwell], you do this. Gilmore [bassist Gary Gilmore], you do this. Taj, do your thing, and I’ll come on in.” That’s how we made records. We didn’t go away, practice and come back.

The bass line and my guitar part work really tight together on “Corrina,” but when I go to the five chord and play an E, the bass plays an Ab against it. Keb’ Mo’ told me that The Natch’l Blues changed him around all over the place. He said that he had it in his car for years until somebody stole the stereo out of the dashboard.

Anyway, he noticed that I never had more than one trick in each song. Some guys were technicians that played a million “watch me, Mom” licks in each song. I wanted mine to be the simplest, cleanest real music amidst all the craziness.

Like a lot of the tunes, “Corrina” was one that I had heard in another form. It was by Big Joe Turner. [He launches into a rockabilly version with the “where you been so long” lyric. Turner cut “Corrine, Corrina” in 1956, but the song goes back much further.]

Acoustic guitar players are probably most familiar with the Leo Kottke version, but it’s so different from yours that it seems like another song. A lot of different people did it. So who actually wrote “Corrina”?

Well, there isn’t anybody that actually wrote it exactly. There are a lot of songs like that.

Is that Duolian the same sound we hear on “She Caught the Katy” and “Take a Giant Step”?

Yes. I always wanted a big slice of acoustic in the electric band. I wanted air and wood in there.

On the second disc of your third album, De Ole Folks at Home, acoustic instruments take center stage for the first time. Did you really lock yourself in a trailer with a bottle of booze to learn banjo?

Oh, yeah, I really did, with two fifths of Jack Daniels. I came out playin’!

Can you please tell the story of “Fishin’ Blues”?

The backstory is that I’m a fisherman [points to the large marlin pendent on his necklace]. The original “Fishin’ Blues” was recorded by Henry Thomas [Mahal plays the 1928 recording on his phone]. On the lead breaks, he plays quills. He had them in a rack around his neck so he could play quills while strumming the guitar. In the old days, he had the rack drilled into his guitar.

That sounds a lot like “Goin’ Up the Country.”

Henry did the original recording of that as well.

Thomas plays with a similar tick-tock type feel that’s in a lot of your stuff.

Yeah, because it’s dance music, man! “Honey, Won’t You Allow Me One More Chance” is by the same guy. That’s where Bob Dylan got “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance.”

He says, “I don’t remember who it was that I heard play it.” All right, Bob. I think he knew a good melody when he heard it. But I’m glad he put it out there. I’ve listened to a lot of stuff because of him. My favorite album is John Wesley Harding. He showed the studio musicians the songs, and then they went right in and recorded them.

That’s why there’s such a sense of immediacy, rather than it being charted out in the standard Nashville numbering system, with everything worked out accordingly. I love Chet Atkins, but some of his stuff is too studied for me. I got to play with him, Johnny Gimble [fiddle] and Peter Ostroushko [mandolin, fiddle] in Hawaii.

What was that experience like?

It was wonderful. I always liked him. It’s amazing to watch a country-twang guy cross his legs and casually pick up a nylon-string, saying, “Well, now I’m going to play this one,” and then completely dazzle on it that easily.

Can you share some details about the resonator you’re holding in your hands [often with a Shubb capo at the second or third fret]?

It’s a Regal. I have two of the same model [RC-56 Tricone Resophonic, with a copper-plated brass body], one for home and one workhorse for the road. Fatdog at Subway [Guitars, in Berkeley, California] set it up with a slotted headstock, a very cheap pickup inside, and an upgraded set of cones. [Fatdog says it was a boutique set he bought from Beard Guitars.] I just like the feel of this Regal.

Is that your desert island guitar – meaning, if you had to pare your collection down to just one, would that be it?

If I had to pare it down to one, I’d give them all away and just stop playing! [laughs] Gimme all or none.

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com