“You Have to Account for 'Tales'…I Don’t Think We’d Be the Same Group Without It”: Steve Howe Talks Yes's ‘Tales From Topographic Oceans’ and Other Milestone Albums

As Yes release their second album in two years, the guitarist reflects on the 50th anniversary of ‘Tales From Topographic Oceans’ and his newly reconceptualized take on the debut album from his 1960s band Tomorrow

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

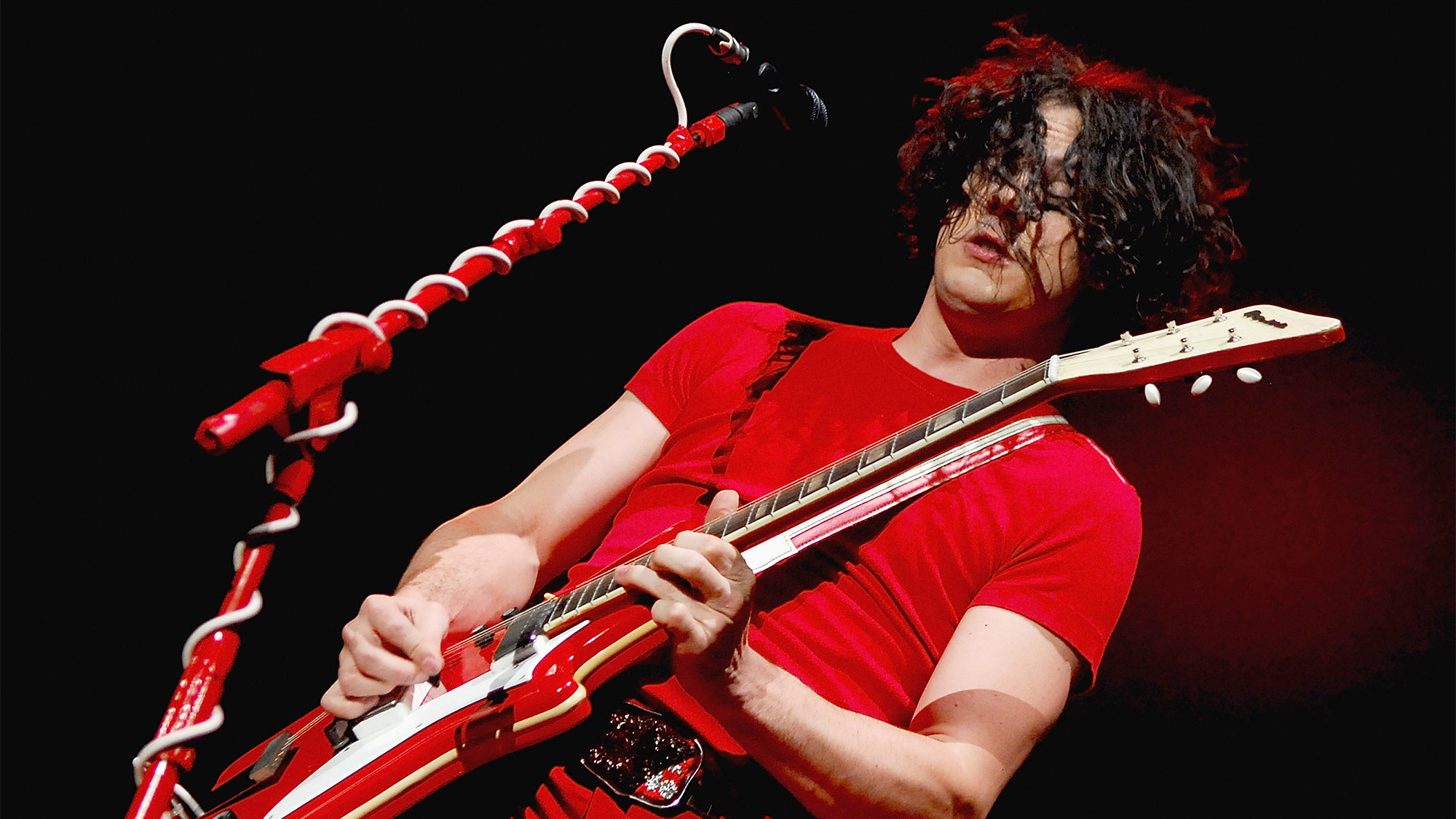

“It was a time of spreading our wings, a wonderful project where we went to the ends of the Earth to do it,” Yes guitarist Steve Howe recalls of Tales From Topographic Oceans, the epic double-vinyl concept album the group released in 1973. Fifty years on, the record remains an important milestone in Yes history for the guitarist. “There was often a feeling that disaster was almost about to strike, but we got there in the end. You have to account for Tales in our history to properly talk about what Yes achieved, because it was quite exceptional. I don’t think we’d be the same group without it.”

Most certainly they wouldn’t. Following on the heels of the critically and commercially successful albums Fragile, Close to the Edge and Yessongs, Tales From Topographic Oceans was a success on both sides of the Atlantic, albeit one that divided critics and fans with its ambitious musical aims. It took a mauling in the music press. Worse still, shortly after its release, keyboardist Rick Wakeman departed the group, bored by the new direction and eager to enjoy his recently launched solo career.

But at its inception, Tales was an exciting project, at least for its originators, Howe and Yes singer Jon Anderson. After composing the lengthy, ambitious tracks on Close to the Edge, Anderson was keen to explore more elaborate musical structures. In March 1973, he had been turned onto the memoir Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda, a guru known in esoteric circles, who had also made an unlikely appearance on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, sandwiched between H.G. Wells and James Joyce. The book had a profound effect on Anderson. “It started me off on the path of becoming aware that there even was a path,” he says. Moreover, he discovered in the book a reference to the different levels and divisions within Hindu scriptures, providing him with a framework in which to place the large-scale musical ideas and concepts he’d been mulling over. He found a willing ally in Howe, with whom he’d co-written both “Roundabout” and “Close to the Edge.” “We were really up for the big, challenging things like, ‘Let’s do an album with four Close to the Edges,’” Howe says with a laugh.

Zooming in with Guitar Player from his “second home” in rural England, away from the hustle and bustle of London, Howe seems relaxed and at ease, not at all like the guy who’s seemingly been working his tail off in recent years. Keeping Yes alive and on the road, save for the pandemic pause, has certainly been part of that. Howe, 76, has shepherded the band through the deaths of founding bassist Chris Squire in 2015 and longtime drummer Alan White last year.

He has also stepped up and into the producer’s chair, helming 2021’s The Quest, Yes’s first new studio album in seven years, and its follow-up, Mirror to the Sky, which came out earlier this year. On top of that, he re-imagined Permanent Dream, the 1968 debut album by his pre-Yes band Tomorrow, by refining the mixes and adding lesser-known studio tracks, and released a new solo album Love Is, as well as a seventh edition of his Homebrew series.

In that regard, the current year has been one of looking both backward and forward for Howe. It was in that mindset that he joined us to share his thoughts about Tales From Topographic Oceans, as well as Tomorrow’s Permanent Dream and Yes’s Mirror to the Sky.

TOMORROW – ‘PERMANENT DREAM’

What led you to re-imagine the Tomorrow album?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One day I was digging around and found the record. I put it on and thought, This shouldn’t sound like this; how can I listen to Tomorrow where it sounds any good? I’ve been friends with [Tomorrow singer] Keith [West] all this time. We eventually ordered the original mono tapes, because I believed it was much better in the mono world, but there were none really available – maybe an odd track or two. So we didn’t remix the whole album. All we could do is treat parts of it with the technology that’s available now. I just fixed all the things that were fixable. Fifty-five years was probably a long time to wait to work on this album, but I’m glad we did what we could.

What kind of perspective did it give you on Steve Howe back then and who he grew to become?

It’s my pathway. It’s where I’ve been. I can go back there and still play Tomorrow music quite easily, doodle around with it. But, yeah, it’s kinda like my early steps. I quite like some of the sounds. [Abbey Road engineers] Peter Bown and Geoff Emerick did a lot of that engineering on my [Gibson ES-]175, and I really like that sound they got for me.

Tomorrow were recording at Abbey Road while the Beatles were working there, too, right?

Yeah. One day Paul and Ringo came in together and put their heads around the doors, like, “Hi guys!” People were very friendly there. It was very nice. There were a few times we’d maybe go downstairs and hear music coming out of the door and think, “Omigod! That’s the Beatles! Omigod!,” and we’d sneak in to not disturb anybody.

It seems kind of ballsy that a young band like Tomorrow would cover “Strawberry Fields Forever” on Permanent Dream, not very long after the Beatles put it out.

[laughs] It was really quite a fresh song, yeah. I don’t know how we got that idea. Someone must have said, “I like that. Why don’t we try it?” It’s very unusual we didn’t choose another song, really, but we loved that one. It’s such classic Beatles.

YES – ‘TALES FROM TOPOGRAPHIC OCEANS’

Tales from Topographic Oceans turns 50 later this year. Before that came Yessongs, which was Yes’s first live album. Did surveying the group’s music up to that point for Yessongs have an impact on where you wanted to go on Topographic Oceans?

I guess doing Yessongs gave Jon and me more of a chance to finish up songs we’d written and to be able to present something in a rehearsal room. ’Cause you had to be quite brave; you did it on your own – “Here’s my song!” – or, in the case of Topographic Oceans, two people. Jon would sing, and I’d noodle my riffs and things, and the band would listen and get their ideas. That’s how we did it. There was a rehearsal period, and then we went into the studio to start recording, and we were there for months and months. We kept plowing on until this thing was finished. It was a huge, huge undertaking.

Rick Wakeman expressed some reservations with Tales and subsequently quit the group. Was it a hard sell to the other guys at the time?

Jon and I asked the guys to be as creative as they could: “Don’t complain that you don’t like it. Find something to play, and then you’ll love it.” There was that adage to everything. So it was a bit of an open book, and we did give everybody credit for their contributions, either structural, chordal structures, or a riff or some vocal line – not the whole song, obviously. So there was a Yes-style credit for music by everybody, but of course Jon and I wrote the majority of the music, and they wouldn’t deny it. But all of them came up with a little bit to add to it, something they wanted to do. We just attempted to draw those things out of them so it was a worthwhile album.

It was a bit polarizing when it was released, wasn’t it?

It was, yeah. But I find it so funny that anybody criticizes this album on the basis that it was a concept album. Out of the 22, 23 studio albums we made, one of them is a concept album called Tales From Topographic Oceans. Can you please allow us to make one concept record without getting on our case? We stuck our necks out with Tales, and some people wanted to chop our heads off for it.

How does it hold up for you 50 years later?

I’ve listened to it quite recently and, y’know, I’m still very proud of it and very pleased with it. There are things in there you never would have thought Yes would do, particularly on side two [“The Remembering (High the Memory)”] – some beautiful, unusual, folk-like, almost Jethro Tull-ish things. Then we got really out there on side three [“The Ancient (Giants Under the Sun)”] with time signatures and crazy stuff. And we were playing it live, because you couldn’t do it any way else. The band was watching me, and I was watching them, and I didn’t know where they were! But at some point we met. The articulation on Topographic Oceans, the drama going into “Leaves of Green” [the last movement of “The Ancient (Giants Under the Sun)”] – and then side four is like…“What?!” It’s really big, and it’s got a lot of lovely moods. I think Tales is totally epic, and I love it to bits.

What are your favorite bits all these years later?

I did do a condensed version of Tales on a solo tour in 1993, where I put it together very easily. And one of my favorite bits is [sings portion of “The Remembering (High the Memory)”]. Now that to me is Yes at its most exceptional. It’s not [sings riff from “Roundabout”]; it’s in the beautiful, folky world. Obviously, “Leaves of Green” is great – [Yes singer] Jon Davison and I have been doing that a lot over the last 10 years. And then side four, there’s some wonderful songs on that. Some of the fun Jon and I had there was very uplifting for us.

YES – ‘MIRROR TO THE SKY’

So you’ve got the new Yes album – two in 19 months, in fact.

[laughs] Well, what happened is what happened to everybody. The beginning of ’20 was a bit of a wake-up call. It was fortunate I’d had my studio upgraded the year before, and studio recording was where the energy could go. Suddenly it wasn’t about building the next set list for the live show. It was, “What about an album, then?” We’d started thinking about it, but of course this was the golden opportunity to have a golden harvest of recording.

When we finished The Quest, a lot of music had come in, and when we realized all was still not good with the world as far as touring goes, there was time to do Mirror to the Sky. I’ve enjoyed it a lot, and the guys did too. We’ve made some miserable records in Yes’s career – some were like pulling teeth, and then we’d dash out on tour. So it is quite nice to be able to take time and work on the music. Both of these records were made by everybody having their own sort of process in writing, coming up with the material, then sending it to HQ, which is where [engineer] Curtis Schwartz is. Then I’d go in and sort of sift through it at his place. What you’re hearing is Yes in 2023, and it is a team. It isn’t Steve Howe and his bunch of cohorts trying to emulate Yes. You’ve got to be Yes to really do what Yes can do.

That’s an interesting statement. What does it mean to be Yes? I think it’s a shared belief together now, but also in line with everyone that’s been in it before. Because, in a way, nobody can replace Jon [Anderson] or Chris [Squire]. All the people who have been on that journey have contributed enormous things. It’s a bit like a Star Wars sequel: You have Star Wars and another Star Wars and another Star Wars.

So Yes are like an undefined story of how music can be developed, of how people can take adventurous ideas, and the thread that sort of runs through it all. I think that’s what the Yes idea is. You have to know that story. It’s like a taxi driver: You can’t drive around New York unless you know New York, if you know what I mean. You have to know that story.

What’s on Mirror that you feel was different or new for you as a player?

“Cut From the Stars.” That came into the album late, and I’d already used every bit of gear I had in some way. So I just got out an analog pedalboard, plugged it in, and stuck it in an amp and put a mic there, and just recorded in more of an old-fashioned style. I enjoy doing that kind of live-guitar thing, more like the ’60s and ’70s stuff. I like to know about 80 percent of what’s going on, and that last 20 percent that I don’t know what’s going on, that’s great. I don’t want to know. Of course what I play has to work with it, but that’s where improvisation came into play. Basically, I just had a nice time just developing a guitar part.

Do you accept the idea that this year, after all the lineup changes, Steve Howe’s guitar is the defining voice of Yes?

Yeah, I guess I’d have to admit that maybe I’ve always believed that, but not any less than Jon Anderson’s voice was an integral part of Yes – at a time, an essential part. But I have had this great opportunity to continue that path, if you like, of working out how to develop it. It’s very flattering to consider that, but I won’t dwell on it too much. I just think it’s what I do.

Is it hard to push that into different directions, then?

Not really. I mean, I love my 175, and I know that’s got a kind of association with Yes. It was on so many things early on, a lot of lead guitar solos, because I was just so fluid on that one until I switched to the Les Paul Jr. for Topographic Oceans. Back in the ’70s I was searching to find out what guitar was the guitar, leaving the 175 aside a bit and trying all the stereo guitars and all of that. Obviously, I’m just so lucky to never lose sight of the fact that it was still me coming through, even if I played an ES-5 Switchmaster. It was still me.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.