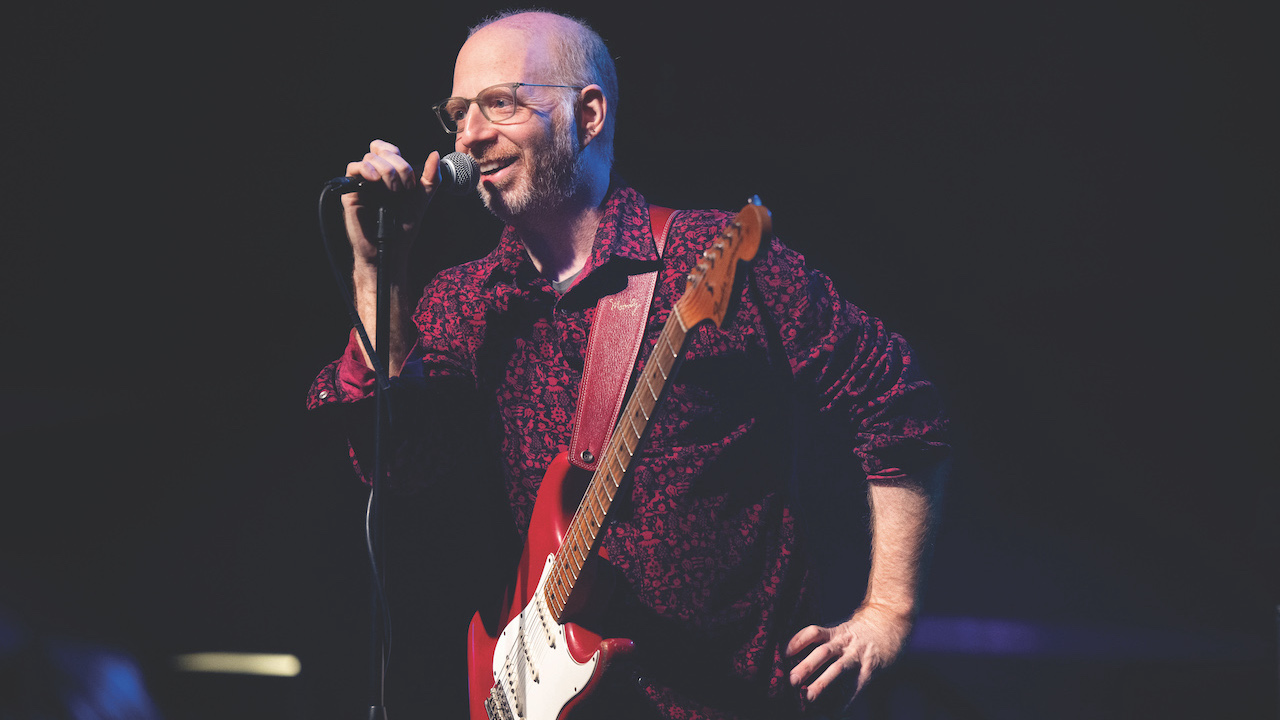

"It’s always going to be random — it’s never going to sound the same. Sometimes it’s great, sometimes it’s not so great": Jazz guitarist Oz Noy on the spontaneity and experimentation of looping and "dancing on the pedals"

His new live album Triple Play is a laboratory of sonic experimentation. Oz Noy tells us how fusing modern effects with inspiration from legendary jazz and blues heroes became central to his process

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

While some guitarists are adept at tweaking their tones through a variety of effects from song to song, Israel-born fusion maverick Oz Noy is like a virtuoso tap dancer on his pedalboard, meticulously coloring with tones and textures, often from bar to bar. It’s an intuitive skill that he’s developed since moving to New York in 1996, the sonic equivalent of an unassisted triple play in baseball.

Growing up in the ’80s in Tel Aviv, Noy gravitated toward American jazz and blues, as well as a bevy of shredders that includes Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, Eric Johnson, Richie Kotzen and Greg Howe. He came to New York as an experienced pro, having held down a regular TV gig and performed numerous studio sessions around Tel Aviv. Rather than bursting on the Big Apple scene right out of the gate, he laid back and observed, taking in performances at Small’s, the West Village hipster subterranean club, by regulars like organist Larry Goldings, pianist Brad Mehldau, tenor saxophonist Joshua Rodman and guitarists Kurt Rosenwinkel and Peter Bernstein while sitting in at the late-night jams that commenced at 2 a.m.

Gradually, Noy began making an impression through his unique vocabulary that organically blends rock, funk, R&B and jazz. Within a couple of years, he had built a fanbase educational facility in Maryland, Triple Play shifts from the slamming opener “Zig Zag” to the decidedly jazzy tribute number “Groovin’ Grant” to a trippy take on Thelonious Monk’s “Bemsha Swing.” From there it’s on to a roadhouse blues (“Boom Boo Boom”), a jazzy shuffle (“Chocolate Soufflé”), a drum and bass–fueled number (“Looni Tooni”), an evocative and lyrical solo piece (“Twice in a While”) and a nasty-toned funk workout (“Twisted Blues”). Along the way, Oz dances on the pedals, adding loops, new tones and textures so seamlessly that it sounds like overdubs. But it’s all live and in the moment.

Guitar Player talked to Noy by phone a couple of days before he embarked on a tour of Italy with Dennis Chambers and Jimmy Haslip in support of Triple Play.

I caught the trio on your stateside tour this past summer when you played Infinity Hall in Hartford. It’s such a powerful, flexible group. How did it come together?

Jimmy’s been touring with me for a really long time, maybe 10 years or so, mostly with [drummer] Dave Weckl. The first time I played with Dennis was in the Moshulu Band, a short thing that went down in 2019 with me and him, guitarist-keyboardist David Sancious and bassist Jeff Berlin. We did two tours — Europe and the States — and that was it. After that, Dennis started to play in my band and we did a European tour. Then I called him in 2020 when I was doing Snapdragon, my last studio album. Right after that, the pandemic hit, and when it started to loosen up, we did a bunch of tours.

And that’s really pretty much the reason I recorded Triple Play, because we had just finished this European tour and the band sounded really good. And I was like, “Man, this is a good chance to record this before it goes away.” You hit a peak with a band. It can come back as something else, but I didn’t want to lose it, and I didn’t know when the next tour would be. So I just forced them. I was like, “Hey, we gotta do it like before the end of the year.” We went into the studio between Christmas and New Year’s.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One of my first observations after seeing you play live was that you have such great facility not only with your fingers but also with your feet on the pedals; and a facile mind that allows you to make quick decisions about coloring with different tones and textures. Where does that vocabulary come from?

When you play in a trio setting, which I’ve done for a really long time, there’s

a lot of sonic space to cover, especially depending on what kind of music you’re doing. My music has changed over the years, but it was always based on groove, and it was never too busy. I don’t like when people play too busy behind me. There should always be enough space in the music to create.

The thing with the pedals came about because I had that space to play with. And sometimes things happened when I pushed a pedal by mistake, and I’d go, “Oh, that’s cool!” But it’s not all accidental. A lot of it has to do with the compositions. Some sections might ask for a certain chord or note or texture.

I might think, I’ll put a tremolo here or a Leslie sound there or a delay here. So that became a part of the composition for me. And it’s easier to do because there’s space in the music for it.

Like on your tune “Chocolate Soufflé” from the new album: You have that Leslie effect going on, so it sounds like you’re playing an organ, comping for yourself.

Yeah, exactly. The Leslie effect happened because I was actually thinking about organ players, where they can comp with the left hand and play these great lines with the right hand. You can’t really do that on guitar, but you can fake it, where you can play the chord before the line or after the line, and it will have the same effect. So I put the Leslie on the chords, just to divide between the two.

A lot of people think that my Leslie has a momentary switch, where you just hold it down with your foot and it works, and then you lift your foot up and it stops. But actually, every time I engage the Leslie, I have to tap twice to turn it on and off. So it’s a lot trickier than it seems, and it takes a certain technique to do it. But I got used to, as you say, “dancing on the pedals.” It became second nature.

Was that something you developed in Israel or did it happen in New York?

All that stuff was developed in New York, and specifically at the Bitter End. I developed all the music for all my albums there. I used to play there every Monday night, so a lot of stuff just happened from playing live there every week and from doing tours.

So the Bitter End was like a laboratory experience for you?

Oh, absolutely, 100 percent. Still is. I would never be able to do my records without that.

You’re in and out with the effects, meticulously painting with sonic textures and colors. It’s quite a juggling act.

I guess so. I’m used to it. But you gotta find your balance. And those things are almost a part of the music for me. Like on “Chocolate Soufflé,” there’s a couple of chords that I always put the Leslie on, and just for those two chords. So that Leslie sound in each particular place is almost like part of the composition now. And if it’s not there, it sounds to me like something’s missing.

You’ve adapted a nimble ability to switch back and forth between a roadhouse blues feel and a jazz feel, sometimes within the same tune. It’s a very organic balance between an earthy thing and a swinging thing, with elements of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Wes Montgomery. How did you so seamlessly incorporate those styles into your playing?

I don’t know. Growing up, I was studying bebop, so I was heavily into Charlie Parker and Wes Montgomery. But on the other hand, it was the ’80s, so I was playing Van Halen’s “Eruption” too. So that didn’t really click together at all. And I remember people telling me, “Oh, you have to decide what you want to do.” But I liked both. I think what put things together is that when I moved to New York and started to do my trio, I wasn’t playing swing music; the grooves were more like R&B or blues grooves. But harmonically I could have gone wherever I wanted.

You hit a peak with a band. I didn't want to lose it, and I didn't know when the next tour would be

And at some point I just let it go and thought, Well, I’ll just play everything

I know on this groove. And that liberated me to go for whatever I wanted. To me, it’s all one thing now. So wherever I want to go to now, whether it’s more bluesy or more jazzy, it’s the same thing. And I try to make it just one thing.

Talk about the opening track to Triple Play, “Zig Zag.” There’s a bit of a Stevie Ray– meets–John Scofield vibe to that tune.

To me, it’s more like I wanted to write my own version of the Meters’ “Cissy Strut.” Harmonically, it’s a minor blues. So I basically wrote a “Cissy Strut” minor blues in my head.

You seem to slip a Monk tune into your albums every once in a while. “Blue Monk,” “Evidence” and “Five Spot Blues” have all appeared on your records.

I love Monk for many reasons, but the one thing that is cool is that his compositions can go in many different directions. With Charlie Parker tunes, for instance, they sound really good when you swing them, but when you try to put other beats on them, they sound a little cheesy. Somehow with Monk and the way he writes, it can go so many ways and still sound good, not forced. So I’ve always found Monk tunes that I can manipulate to put into my own band. I just thought it sounded organic, even if it wasn’t swinging.

You take some great liberties with “Bemsha Swing” on the new album.

Exactly. The other thing with Monk is you can twist the harmony a little bit. Maybe we’re playing the wrong chord here or there, but I don’t really care. To me, it still sounds organic and it works in the concept of what I do, bending it a little bit here and there.

On the solo section to “Bemsha Swing,” for instance, I’m not actually playing Monk’s changes. I simplified it. I wanted to make it more like a Bitches Brew vibe. When I play the melody, it’s still Monk’s changes, but when it goes to the solos there’s a vamp section that’s more open, where I do all these loops and stuff. And on the solo section, I simplify the chords to I and IV. That’s what I like about Monk — you can morph it into what you need it to be, if you find the right tunes. It doesn’t work on every Monk tune, obviously.

How are you generating those loops on “Bemsha Swing”? It’s like you’re holding a chord, then soloing over it.

I do it all live with a Line 6 HX [multi- effects processor]. It’s sneaky, because you don’t notice when I’m recording the loop. Sometimes I’ll record a loop while I’m in the middle of a part, and then I manipulate it with my foot and put it into a section. For example, I’ll loop part of the melody and then reverse it and double-time it. And then when it comes back in it, because it was in a weird spot, it doesn’t sound like anything that you heard before. But I do it while I’m playing live, which is always a mindfuck.

I can imagine. You’re already busy playing the tune, but you’re also acting like an engineer at the board.

Yeah. And there’s a certain amount of planning in advance to pull that off. It’s like, Okay, if I loop here, it’s going to come there. So it’s something that you have to get used to. But I’ve been doing the looping thing for a long time, and what I really like about it is it’s always going to be random — it’s never going to sound the same. Sometimes it’s great, sometimes it’s not so great. But at least what comes out is mostly surprising. So then, if you just commit to those loops, it’s cool. And on the new album there were some cool moments where I was like, Oh wow, how did I do that? And that’s always cool.

Your chord melody playing on the intro to “Snapdragon” is very accomplished. That was the title track of your previous studio album but it has an almost kind of “Manic Depression” vibe... a little Jimi Hendrix Experience influence coming into play.

Yeah, but I actually wrote that tune over Joe Henderson’s “Black Narcissus.” So basically, I took those chord changes and added a “Manic Depression” vibe to it.

What was your approach on the solo guitar piece, “Twice in a While”?

That’s a tune that I recorded with a full band [Lee, Weckl and keyboardist Chris Palmaro] on my fourth album, 2009’s Schizophrenic. It’s a really catchy melody and I always liked the composition, but I’m at the point now where I didn’t want to play it with a band anymore.

Actually, a lot of people at the Berklee College of Music and on YouTube have transcribed my solo on it from the original album, and a lot of times people ask me to play it at gigs. But I’m so over it in terms of where I’m at now. So I thought it would be both a challenge and a nice thing to play the tune solo, because I think the melody and the composition are strong enough to hold up.

What guitars are you playing throughout this live album?

I’m switching between two Fender guitars: a Stratocaster and a Telecaster. But I would say that it’s 60 percent Strat, 40 percent Tele. Both are from the John Cruz Custom shop.

That Leslie sound in each particular place is almost like part of the composition now

How did you get that nasty tone on the Triple Play closing track, “Twisted Blues”?

I’m playing a Telecaster with a signature pedal that Xotic made for me called the RC/AC Oz pedal. It has two different gain stages, so one is always on and the other one is the solo section. It’s essentially their RC booster into their AC booster. I use the RC/AC Oz pedal on most of the album.

And actually, I haven’t played “Twisted Blues” in a long time because it’s the title track of an album I did 12 years ago. I try to play the latest stuff. But that tune has such a funky groove, and I had a feeling Dennis was going to really sound great on it. He brings his own thing to it that’s really strong.

You’re very particular about your sound and meticulous about your tone. What amp will you take with you on tour?

I don’t take amps on tour. I have amps at certain places in the U.S. For example, on the East Coast and in California I have Two-Rock amplifiers. Everywhere else, I have to rent stuff, which is a bummer. I was thinking of leaving an amp in Europe at some point, because it’s really challenging when you rent amps. It makes life harder.

When we were doing our last tour in the U.S., we played a bunch of shows where I had to rent an amp, and it sounded fine. But then we did a show and I brought my Two-Rock amp, and Dennis was like, “Wow! What a difference. It’s like night and day.” So it is what it is. You just have to deal with it.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.