“Paul Reed Smith chooses wood like Stradivari, who used to walk around the Dolomites in Italy tapping on trees, saying, ‘I’ll take that one, not that one.’ He’s a maniac”: John McLaughlin on reuniting with Shakti, his bad year, and his signature PRS

As he reunites his Indo-jazz supergroup Shakti, John McLaughlin talks harmony, rhythm and good wood

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

John McLaughlin’s steel-string work in Shakti is some of the all-time most astonishing acoustic virtuosity, right alongside his hugely influential nylon-string playing with Paco de Lucia and Al Di Meola in the Guitar Trio.

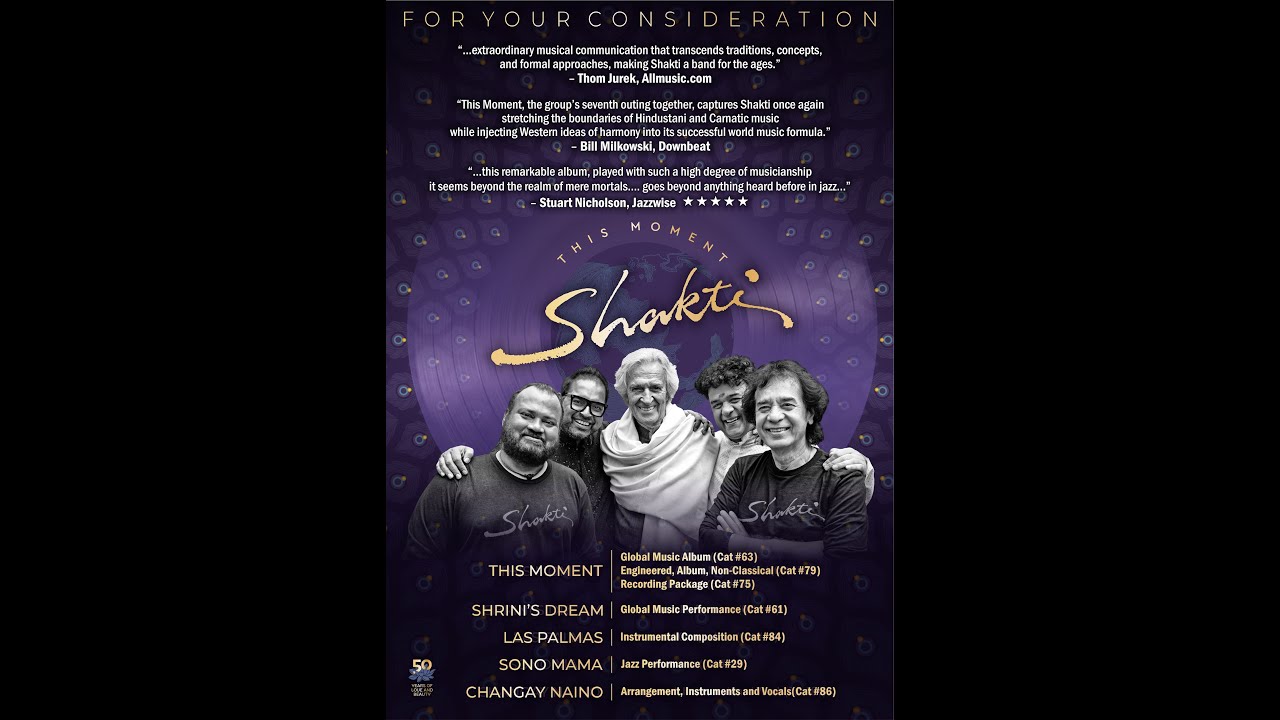

McLaughlin and tabla master Zakir Hussain are celebrating a half century since joining worlds as Shakti by releasing This Moment (Abstract Logix), the group’s first new studio album in 46 years, and going on tour. In September, Guitar Player and SFJAZZ welcomed McLaughlin back to San Francisco, where he has a storied history.

The City by the Bay was the site of McLaughlin’s latest live album, 2018’s Live in San Francisco as well as the Guitar Trio’s celebrated Friday Night in San Francisco album, recorded in late 1980 and released in 1981. In 2022, Saturday Night in San Francisco finally saw the light of day after spending more than four decades gathering dust in Di Meola’s basement. It was recorded the night after the legendary Friday show, and Di Meola produced the project during the pandemic lockdown.

McLaughlin says, “Al called me up and told me about finding the tape of the second show, and it was exciting that the program on Saturday night was different enough to make another album.” Via a Zoom connection from GP’s origin in the Bay Area to McLaughlin’s longtime home in Monaco, the virtuoso goes on to connect the dots of how Shakti and the Guitar Trio have shaped his acoustic career through the lens of the various instruments he’s played, right up to the new, long-awaited Shakti album.

McLaughlin’s playing in Shakti is remarkable on a number of levels. His highly evolved technique pervades impossibly complex compositions that mostly follow unpredictable Indian raga forms full of next-level improvisations. Perhaps most incredible is how the twisting, turning melody lines are so intricately linked with the rapid-fire percussion rhythms. As impressive as the GP Hall of Famer’s playing remains, Shakti serves a higher purpose. The stratospheric level of collective expertise creates a mystical musical vessel designed to take the listener on a transcendental celebration of life. The current lineup includes violinist Ganesh Rajagopalan, percussionist Selvaganesh Vinayakram and vocalist Shankar Mahadevan.

To have a fully functional Shakti at this time is miraculous. Mandolin guru U. Shrinivas passed away in 2014. McLaughlin’s arthritis became so severe that he announced his retirement from touring in 2017. Then the pandemic hit. But rather than let his world stop spinning, McLaughlin took it all as inspiration to keep his wheels turning. Using deep meditation techniques described in his 2021 GP interview, he healed himself.

He recorded the solo effort Liberation Time during lockdown and challenged Shakti band members, who live on different continents, to learn digital recording and video conferencing technology so they could finally collaborate remotely on a new one as well. The result is pure sonic joy, full of fresh tones.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

This Moment presents a contemporary take on the classic Shakti sound, and was — ironically, given its title — carefully crafted rather than recorded live in the moment. It sounds refined, with 21st century elements layered into Shakti’s signature Indian/jazz fusion.

Shakti means “power” and McLaughlin re-energizes the timeless ensemble ina modern way, playing electric guitar and guitar synth in the otherwise acoustic affair. He makes pristine tones from his new signature PRS guitar sound at home in the worldly mix, and he uses a Fishman MIDI guitar controller and software system to conjure an array of sounds, from bamboo flute to synth bass to strings.

How did you come to play electric guitar and guitar synth in Shakti?

There are a couple of reasons. Of course, Shakti was originally acoustic, and I played a very special guitar with 13 strings and a scalloped fingerboard. [The original Shakti guitar, built by Abraham Wechter during his tenure at Gibson, was based on McLaughlin’s favorite model, the J-200, with the addition of seven tunable sympathetic strings running underneath the main six at a 45-degree angle.] Then there was a period that started in 1978 when Shakti percussion player Vikku Vinayakram had to go back to India to run the school his father founded, after his father passed.

It just so happened that I ran into Paco de Lucia when I was in Europe that year. We started to hang out, and that was the beginning of the Guitar Trio. I went from playing the steel-string Shakti guitar to a nylon-string guitar for a classical tone, because Paco was playing a beautiful flamenco guitar. I must have spent 10 years playing the nylon-string. I loaned out my Shakti guitar, because I believe instruments must be played, otherwise they get sick, just like humans. When the Shakti guitar was brought back to me, it was broken.

That was a big tragedy. I kept in touch with Zakir, and all the while I was playing a very fine Wechter nylon-string acoustic. When Shakti got an invitation to tour, I started playing a big-bodied Gibson Johnny Smith [archtop]. At the end of the tour, I was sitting with Zakir and I said, “Shakti is such a beautiful form. We have to find a way to keep going.” We ended up inviting Shrinivas to join us, and he played an electric mandolin with a solid body. He was a genius. I was playing the Johnny Smith Gibson, which has a very sweet, clean sound that went very well with the electric mandolin. We continued like that until we lost Shrinivas in 2014.

That was a bad year. We also lost Paco, and I got zapped with arthritis in the right wrist. It took me until 2019 to cure myself. At my tender age, when I try to play the big Wechter nylon-string, I feel a stress because of the right-hand position. I have to sacrifice playing the acoustic, because I don’t have any problems playing the electric guitar, and musically I’ve never felt better. The other good thing about playing the new PRS is that, through MIDI, I’m able to bring more orchestral sounds from my Western world into the Shakti group.

It makes me happy, and it makes them happy too, because they love Western music as much as they love Eastern music. That’s why we’re here today.

There is so much rapid-fire energy in the music of Shakti, and it’s nice to hear that the PRS is helping facilitate that. This is, technically speaking, your first signature PRS, correct?

Yes, although I first met Paul over 20 years ago at the Frankfurt Musikmesse. Finally, last year, he called up saying that he wanted to make me a signature model. Oh, the tone! He chooses wood like Stradivari, who used to walk around the Dolomites in Italy tapping on trees, saying, “I’ll take that one, not that one.” Paul has got the most astonishingly beautiful wood. The neck of my guitar is made out of hormingo, which is a wood used in marimbas for its sound-producing tines. As a guitar neck, it’s extraordinary. I’ve got three other PRS guitars, but there’s something magical about this one. Paul is a maniac. He’s as crazy about what he’s doing as I am about what I’m doing.

Do you ever miss having a scalloped fretboard, like on the Shakti guitar that allowed you to do bigger bends?

That came about in around 1971 or ’72, when I started studying the South Indian veena, which has got a huge neck with big frets embedded in beeswax. When you bend a string, you don’t push — you pull it, like sitar. But the veena is not curved like that. It’s flat. I spent two years with my guru, Dr. Ramanathan, at Wesleyan University, before I realized my guitar playing was suffering. That way of bending the string, which they call a gamaka, you can do all the way up the fingerboard, but you’ve got to have the space under the strings, and that was the whole point of the scalloped fingerboard on the Shakti guitar. But then I ran into Paco in 1978 when we formed the Guitar Trio, and after 10 years of playing the nylon-string classical guitar, I kind of lost that bending technique.

Can you substitute glissando?

No. That’s a Shrinivas technique. It’s more like a vocal approach. [Imitates a quivering vocal] That’s what I loved about the veena, too. And one of my first adventures coming out of Shakti was I had a luthier make the scalloped fretboard on my 1968 Gibson 345, which is big, but it’s thin.

I’m going to try when I get some time… Well, I don’t have time at the moment, because we started touring India in January, and in rehearsal we started changing and re-arranging the tunes from the new album. We’re crazy. So now I’m busy learning the new arrangements.

They’re so worked out, especially the lengthy melodic runs that you play in unison with the vocal and the violin. Are they written down?

No. Everything is oral. That’s the Indian way. Crazy, huh?

It seems truly impossible.

Everything is sung in India. When you learn, even the percussion players sing the rhythm. In South India, it’s called konokol. I started studying it with Ravi Shankar in the mid-70s. Every time he came to New York, I’d go to his hotel. He taught me the rhythmic theory, and it’s all vocal. Once you get a handle on the konokol system of rhythm, you understand exactly what a drummer from anywhere in the world is doing, because, in a way, it’s all mathematics. It’s mathematics with soul, you know?

And the biggest musical difference is the Western sense of harmony, correct?

They are as developed in rhythm as we are in harmony. That’s how crazy they are. You can hear it on the album in some of the compositions that Zakir and Selva [percussionist Selvaganesh Vinayakram] do in unison. It’s phenomenal.

And it’s apparent when your compositions come from a different place. Las Palmas sounds a bit flamenco in a Paco de Lucia kind of way, and then there’s a bluesy turnaround.

Las palmas is Spanish for clapping. That’s what they call it in flamenco, which is a direct influence, because it was just late last year when they finally did the memorial concert for Paco de Lucia in Madrid. All the greatest guitar players, dancers and singers were there. Oh, it was fantastic. Al [Di Meola] was there too, and we played with Paco’s nephew, Antonio Sanchez. What a monster player! At some point maybe he’ll take the crown. Las Palmas is kind of an homage to that world I love and experienced with Paco.

And what a world of difference it must be playing ragas with Shakti.

Right, there are no chord changes in Indian music. I’m the only Western musician in Shakti, so triggering sounds with the Fishman MIDI pickup and substituting another harmonic structure that gives them a completely different view of the raga are ways that I can bend the rules.

Those guitar synth elements are clear to hear on the introduction to the appropriately titled Bending the Rules. Do you ever break from standard tuning?

I can only play in standard tuning. Don’t ask me to de-tune a string; I will be in deep trouble.

Can you speak about how the improvisational cycles flow in Shakti?

Improvisation is the heart and soul of a band. And it’s one of the great connections Indian music has with jazz, because they’re masters of improvisation. An improvisation is like a moment of truth. You stand up to do a solo, and your trousers are down by your ankles. You cannot hide, so you have to go with it and let it all hang out. You have a structure. You take risks.

And it’s exactly the same for the Indians. They have the raga, but if I slightly modify some harmony underneath, they’ll hear it and go with it.

Another aspect that’s so close to jazz is the rhythm. God bless Ravi Shankar for all the lessons he gave me in konokol, because as soon as we start to play the drummers are on my case, “kicking my butt” as they say. But that’s exactly what I want in music. I want somebody to stimulate me — knock me out of my little niche. All of a sudden, you’re on a tightrope. What are you going to do? You abandon yourself to the spirit, and you go with it. That’s the point where things start to happen.

How did improvisation factor into a remote recording process?

That’s one of the reasons it took two years to make the album. We’d put down some basic files and send them around. Then I’d get files back, and holy smoke, I’d have to redo my part, and the improvisational section too. That would happen with everybody, reacting by abandoning their parts and redoing them three or four times. There was a lot of excitement going on. It didn’t feel at all like I was alone. I’d put on the headphones, close my eyes, push play, and they were with me in the room. We basically went until we couldn’t work anymore. It’s wonderful. We wanted to do a studio album because we hadn’t done one since 1977, but we’ve made some live albums because in a way we’re a live band.

In the Equipment section of your website, there’s a re-creation of your Shakti acoustic from the ’70s credited to master luthier Mirko Borghino. Does it sound like the original Wechter, and have you considered sampling it?

It was about three years ago when the Italian luthier came to see me. He built a Shakti guitar based on photos, and it’s so well made that it does sound like the original. It’s unbelievable. I have thought of sampling its sound. I’m fascinated by that aspect of it, but I’d need some technical training. I do miss the acoustic guitar. I miss the Shakti guitar. My problem is what I mentioned before. That’s what happens when you get old. The attack is wrong on the acoustic guitar samples that I’ve heard. It sounds artificial, and it bothers me. But I enjoy using the guitar synth to get anything orchestral, or perhaps a flute or something to accompany the voice or the violin. I use the Fishman Triple Play Connect system in conjunction with my laptop, and it works like a dream.

What’s the main signal chain for the PRS?

I’m still in learning mode with the new PRS, because it’s got two toggle switches that engage high-pass filters, one for each pickup. So there are a lot of configurations. I like to use different tones for, say, playing arpeggios or strumming chords, but the music happens so fast in Shakti. I have to plan when to switch pickups and when to switch the EQ into the position that I want. I use a [Hermida Audio] Zendrive 2 pedal, and I’m currently experimenting with a [DSM Humboldt Electronics] Simplifier amplifier simulation pedal. You can control the amount of preamp or power amp drive and the sound of the speakers. The fact that it’s all analog is very nice, because I really like the tone. It’s different, very pure. I’m going to try it out for sure. After the Shakti tour when I’m at Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival in Los Angeles [September 24 and 25] I’ll be playing with an amp, of course.

What’s the plan?

I spoke with Carlos Santana, and we’re planning to play together on Sunday night. Maybe we’ll do a couple of golden oldies from Love Devotion Surrender, or from Welcome. Joe Bonamassa invited me to play a tune. I like Joe, and he can sing too, so I’ll probably do a number with Joe on Saturday night and just, you know, jam.

Shakti is very different, eh?

Shakti is a totally different trip.

Shakti's This Moment is out now and available to buy or stream

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com