All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The guitar is a very expressive instrument. In the hands of a master player, it can sing, cry, laugh, scream, hoot and holler, and generally display just about any emotion known to man or beast. And when it comes to nuances inherent to the instrument, few techniques are as emotive as string bending.

From vibrato to half- and whole-step bends, extra-wide bends and pedal steel-style licks, they’re all covered in this ambitious lesson. And to top it off, there’s an extended solo at the end that’s bursting at the seams with a variety of cool-sounding bends. So grab your ax with the lightest string gauges and let’s get going.

Basics

Just to make sure we’re on common ground, this lesson will start with some bending basics. But have patience, things will start moving in no time.

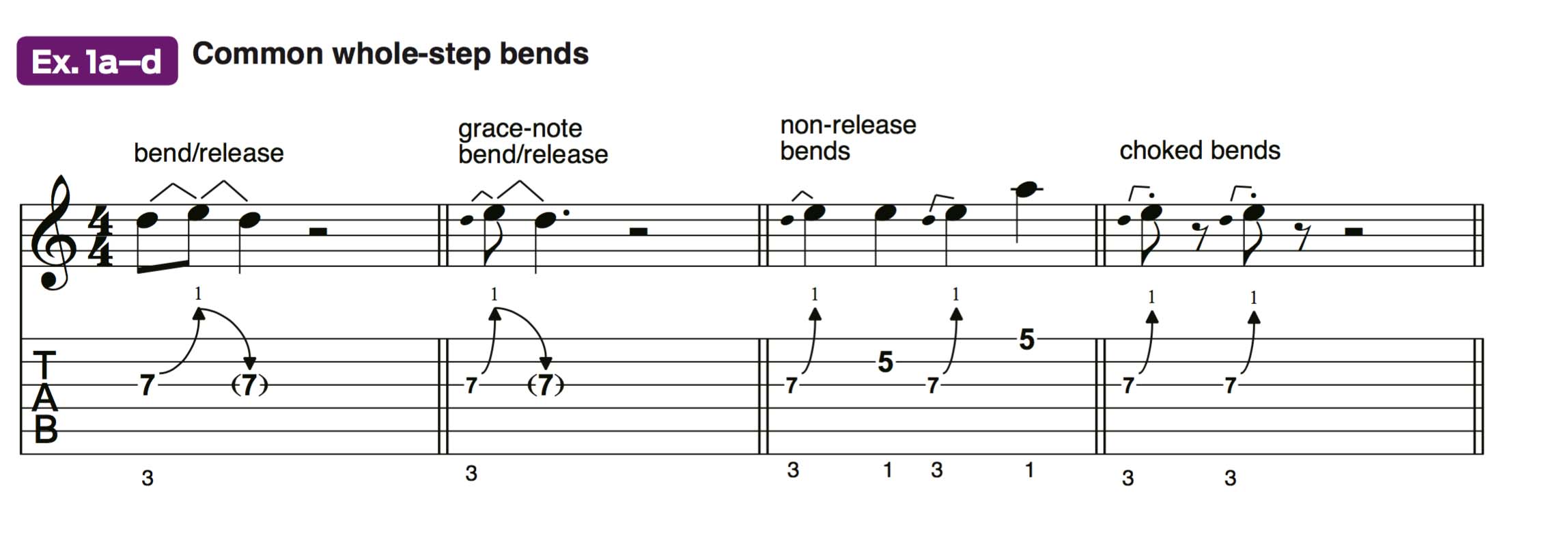

Examples 1a–d show some of the most common bending moves. These are the platform maneuvers used to launch a lot of awesome bending licks. All feature the strongest bending finger – the 3rd, or ring – on the string that most often gets the lion’s share of shoves and tugs – the G.

With most bends, it’s a good idea to wrap your thumb over the neck and squeeze it like a vice. When bending with the ring finger, also enlist the middle, or 2nd, finger to help push the string to pitch, while employing the index finger to nestle against the underside of the D string so as to preemptively mute any unwanted string noise.

Bending direction is a matter of personal preference. Many guitarists will usually bend the G string, or one of the other strings, up and away from the palm, using a pushing technique, while some like to pull the string down and in toward the palm.

The choice is typically made on a case by case basis, considering the musical context, and sometimes there is no choice in which technique to employ, as we will see.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Ex. 1a shows a standard bend and release, performed in an eighth-note rhythm. You pick the note, bend it up, “in time,” to a target pitch (in this case, a whole step up, from D to E) then release it to its original, unbent starting position.

With most bends, it’s a good idea to wrap your thumb over the neck and squeeze it like a vice

Ex. 1b illustrates a grace-note bend and release, which is essentially the same technique. The only difference here is that the bend is a grace note, which doesn’t officially count as part of the metric rhythm of the measure and is quickly inserted right before the target note, “by grace of” the following beat. Grace notes are notated with a smaller size note head and tab number.

Ex. 1c is where things get a little trickier. Here, the same note is bent up a whole step, but it is muted and silenced before the string is released to pitch.

To stop the sound of the release, you can mute the string with the side of your pick-hand thumb as you pick the next note. You can also mute it by simply relaxing your fret hand’s “grip” on the string, meaning loosening the pressure applied to it, but without letting go of it.

The ability to mute a bend before it's released is an extremely important technique and can be challenging to master. In blues-rock soloing it's often the deciding factor that separates the newbies from the pros.

Ex. 1d features “choked” bends. Essentially the same as the non-release bend, a choked bend differs in that the bent note is stopped very quickly, resulting in the sound of a scream or yelp being choked off by throttling hands. Listen to Chuck Berry’s guitar intro to “Johnny B. Goode” for a textbook example of choked bends.

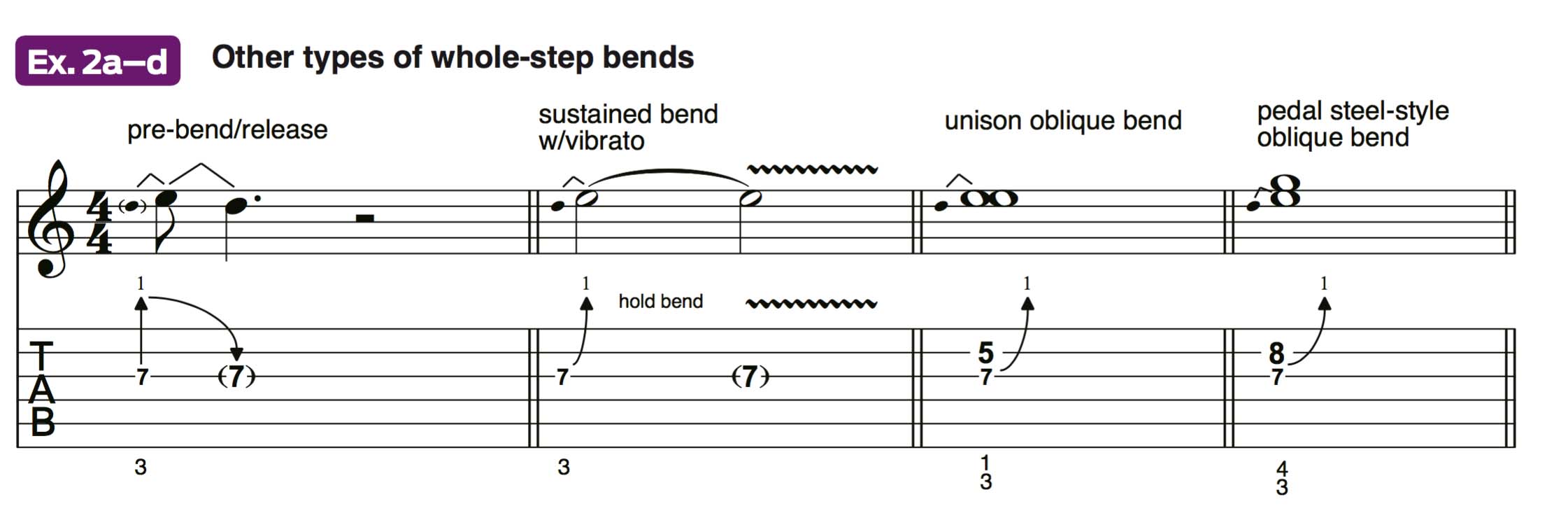

Our next group of examples demonstrate an assortment of more advanced bending techniques. Ex. 2a is a pre-bend, for which the string is bent up to pitch before it is picked and sounded.

(George Harrison’s anchor riff in “Something,” by the Beatles, is a prime example of the pre-bend technique in action.) The pre-bend takes practice to master because the player needs to rely on muscle memory to instinctively anticipate precisely how much bending force is needed to achieve the desired target pitch without hearing it.

Next, Ex. 2b is a held bend that morphs into a bend vibrato, which many guitarists regard as the sweetest-sounding and most-vocal-like vibrato there is. Hold the bend for two beats, as indicated, then proceed to repeatedly release it ever so slightly, by approximately a quarter step, which is half of a half step, then rebend it up to the target pitch, and do so in an even and fairly quick rhythm.

This technique is easier said than done. Spend some time practicing different tempos of vibrato speed. Sometimes slow and wiggly fits the bill, while other occasions call for a quivery approach. (Listen to the opening bars of Eric Clapton’s main solo in the Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” for an exquisite example of heavily-vibratoed slow-release bends.)

The next two examples feature a technique known as the oblique bend, where a dyad (two-note chord) is played on adjacent strings and one string is bent while the other remains stationary.

Ex. 2c is a popular blues-rock oblique bend, called a unison bend, so called because the lower string is bent up to match the pitch of an unbent fretted note on the higher string, in unison. (Jimi Hendrix performed a melodic passage of unison bends in his main solo in “Manic Depression.”)

Be careful here not to bend the B string along with the G string. Concentrate on holding your index finger in place.

Ex. 2d is a classic example of a harmonized oblique bend, featuring a different pitch on each string, which mimics a signature move often performed by country pedal steel players, who use knee- and foot-operated levers to bend notes up precisely a whole step. (Guitarist Bernie Leadon’s first three bends in the intro to the Eagles’ classic “Take It Easy” is a familiar example of this pedal steel-style maneuver.)

Be sure to keep your pinkie planted firmly behind the B string’s 8th fret as you bend the G string up a whole step with your ring finger, supported by the middle. (You can add your index finger too, for extra support and bending reinforcement).

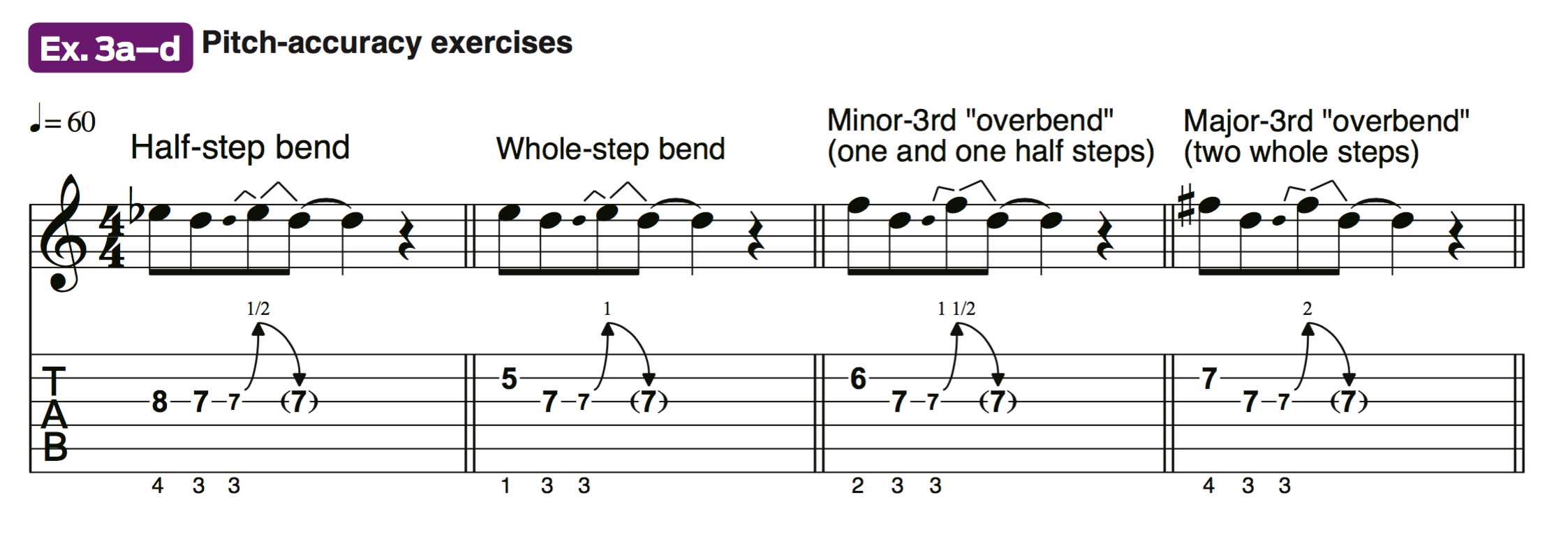

Examples 3a–d present a series of drills designed to help develop your pitch accuracy when bending.

Ex. 3a is a half-step bend exercise. The idea is to first focus on the pitch of the unbent Eb note at the 8th fret on the G string, then try to swoop up to that same exact pitch by bending to it from D at the 7th fret.

Employ the same listening-and-mimicking tactic to play the whole-step bend in Ex. 3b, for which the goal is to bend from D up to E. Examples 3c and 3d feature “overbends,” or bends beyond a wholestep.

These are not for the faint of heart and shouldn’t be attempted until you’re well accustomed to performing wholestep bends. (Light-gauge strings are recommended.) Some legendary players known for their use of overbends are Albert King, David Gilmour, Richie Blackmore, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmy Page and Edward Van Halen.

The Two-Finger Modal Box

It’s one thing to have a few bending licks in your arsenal, but it’s another to have the creative freedom to come up with new ones on the fly. With that goal in mind, here’s an intriguing system that exploits the potential of the mighty ring-finger bend.

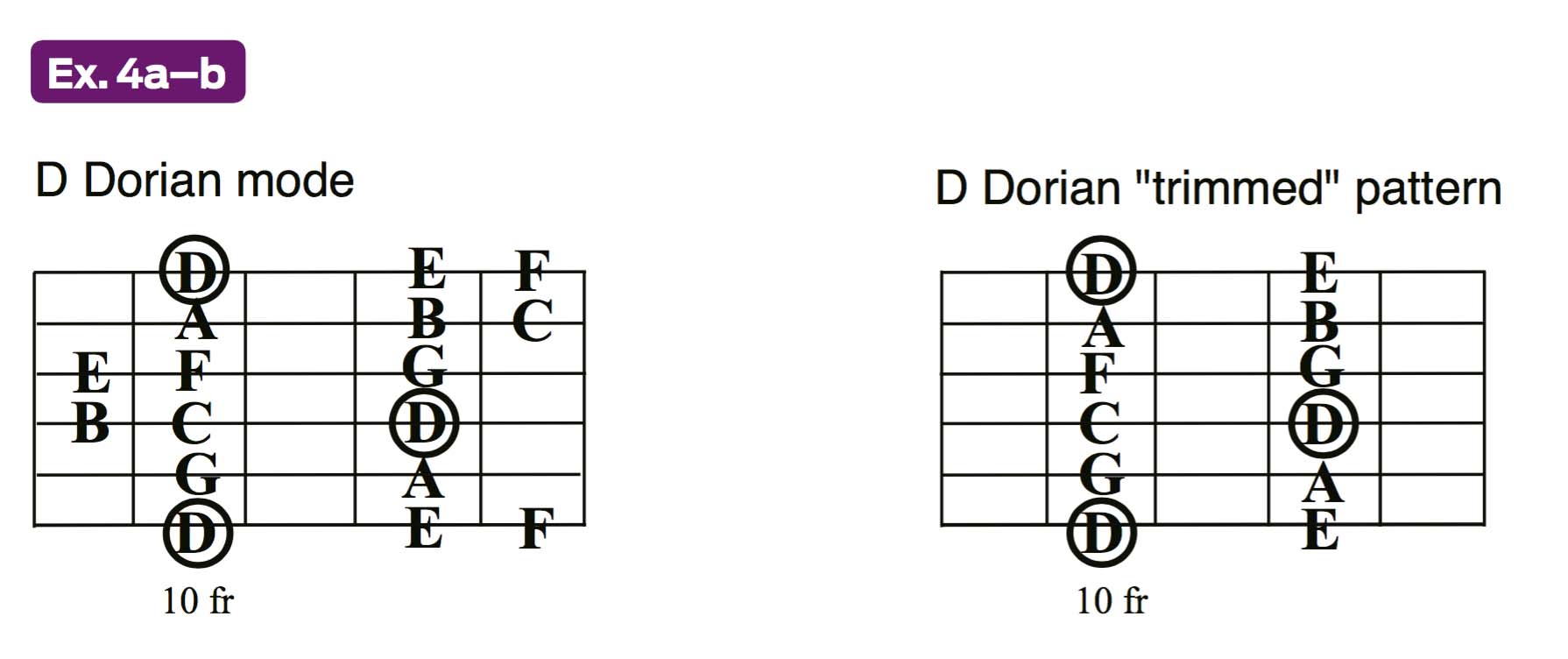

Ex. 4a illustrates the 10th-position box pattern for the D Dorian mode (D, E, F, G, A, B, C), which is the second mode of the C major scale. Dorian is a popular scale choice among soloists in many styles, from rock, blues and funk, to country, metal and jazz. Play through this pattern a few times to get the tonality in your ear.

Then look at Ex. 4b. This is a “trimmed down” version of the full pattern. Certain notes have been strategically shaved off, namely those at the 9th and 13th frets, to allow easy access to a compact range between the 10th and 12th frets and a two-finger method for navigating the melodic structure of the scale using bends.

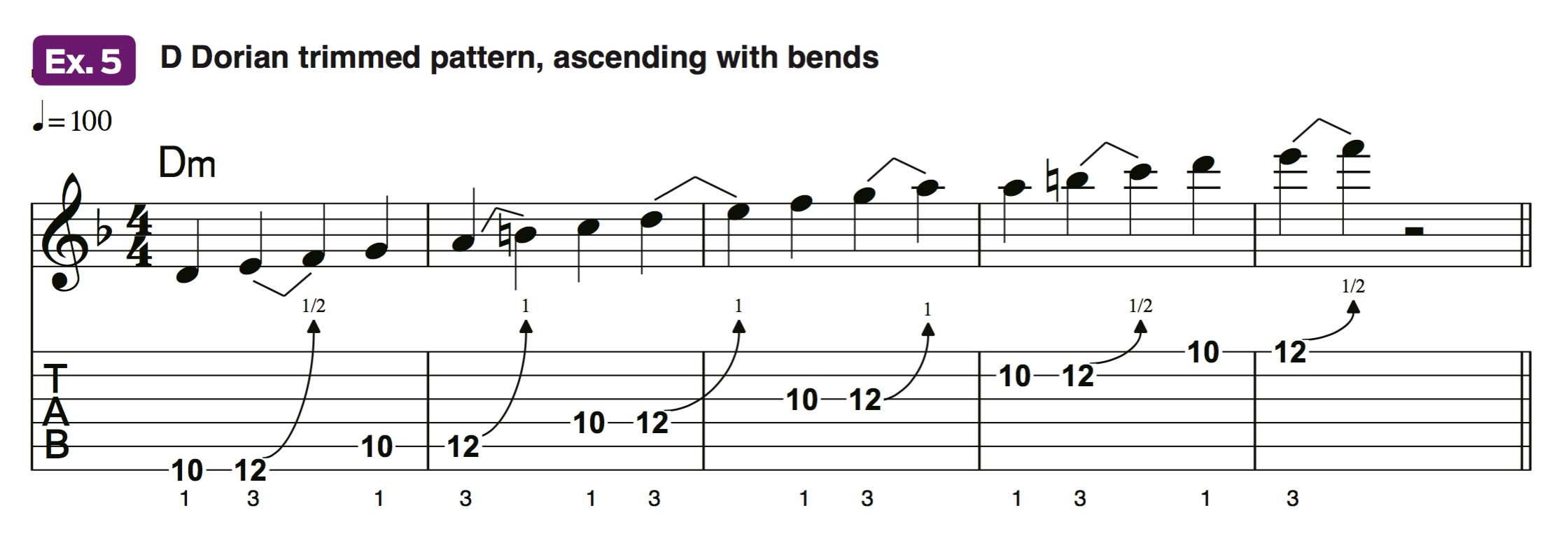

Ex. 5 is an ascending line crafted entirely from the trimmed-down pattern in 4b and demonstrates how, by employing either half- or whole-step bends, it’s possible to play every note of D Dorian in succession, without fretting more than two notes per string.

Be sure to bend the low E and A strings downward (toward the floor), by pulling the string in toward your palm. You can bend up on all the other strings, using the standard push-bend technique.

Ex. 6 employs the same two-digit box shape to descend the scale with a series of bend/release/pull-off sequences. (This is essentially the same technique described in Ex.1b, but with a pull-off tacked on.)

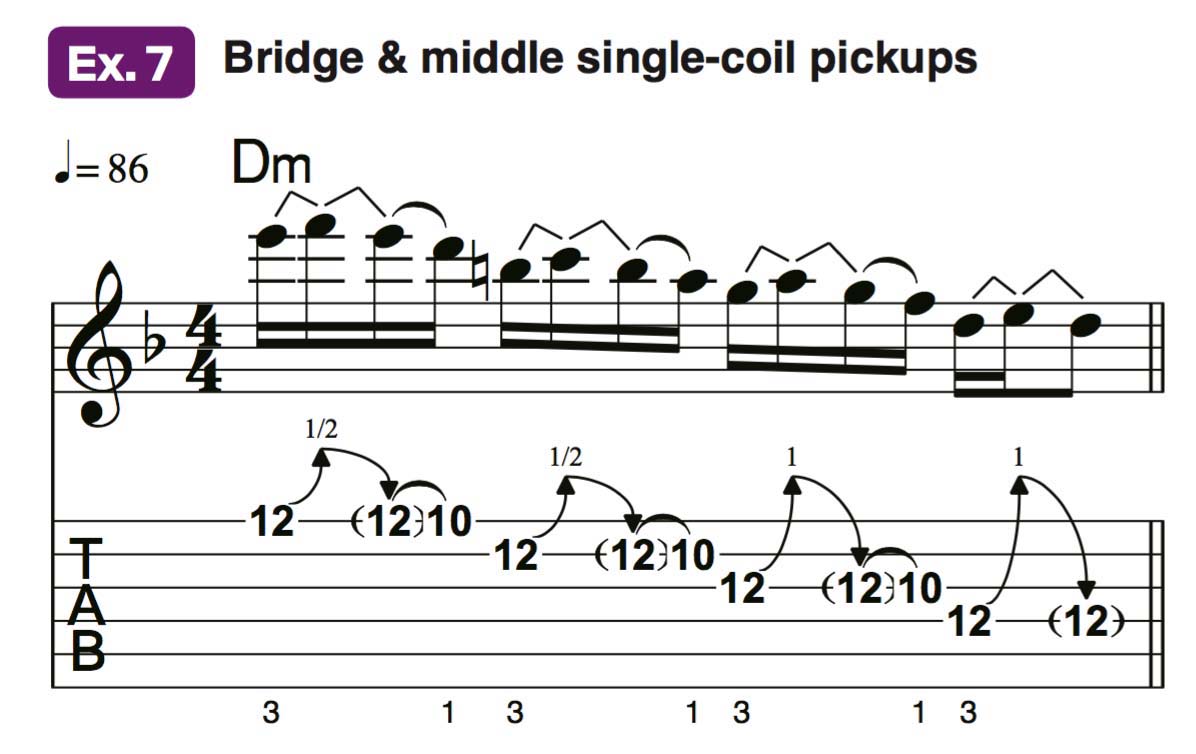

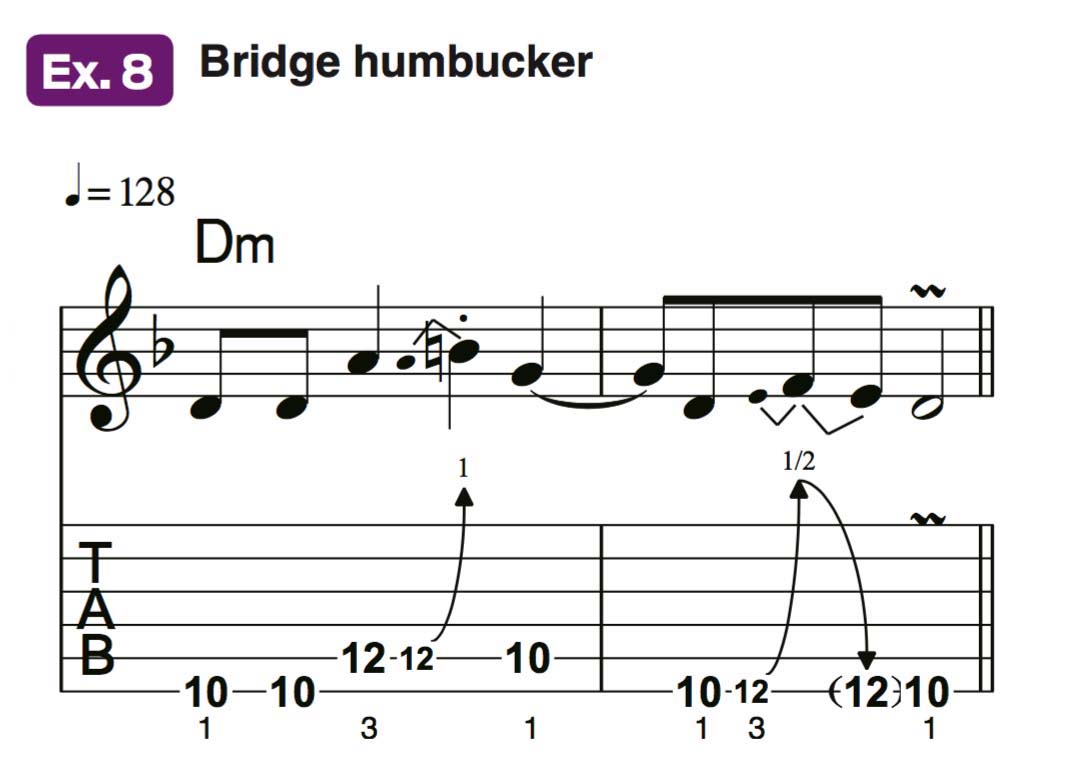

Ex. 7 transforms the previous triplet-based exercise into a 16-note propelled lick, while Ex. 8 isolates the lower strings for a hard-rock example reminiscent of Van Halen’s “Jamie’s Cryin’.”

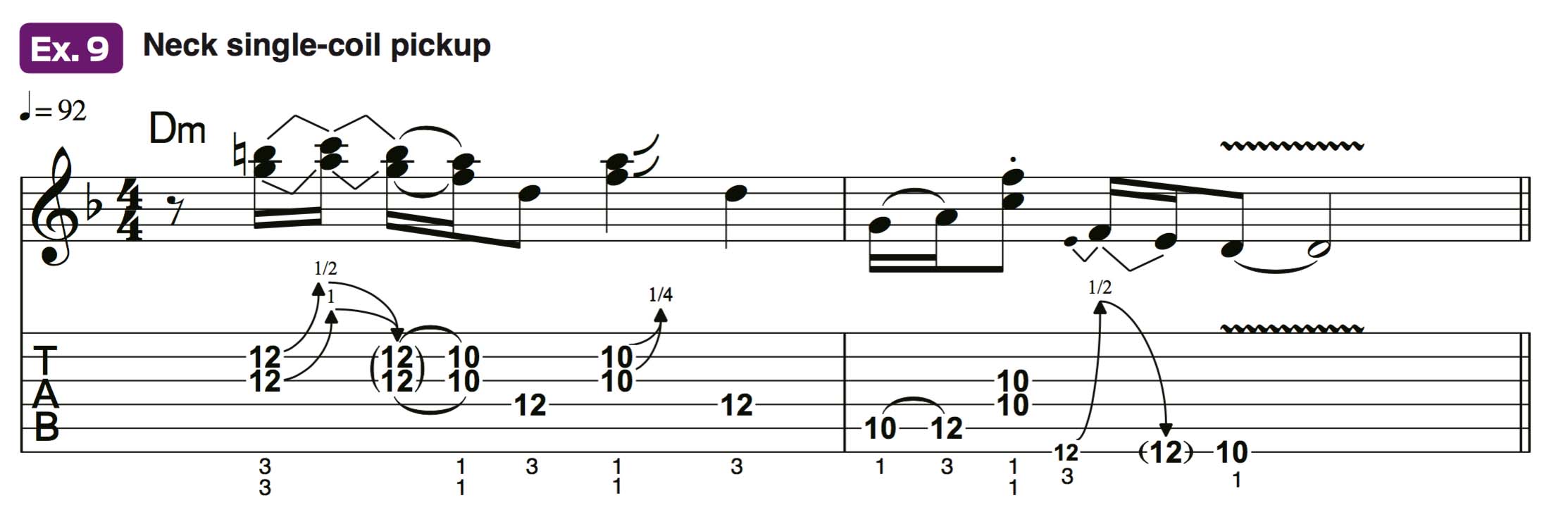

Ex. 9 features an intriguing double-stop bend on the G and B string set. Keeping both strings parallel (equidistant) while bending is key to achieving the proper pitches.

Other 10th-Position Possibilities

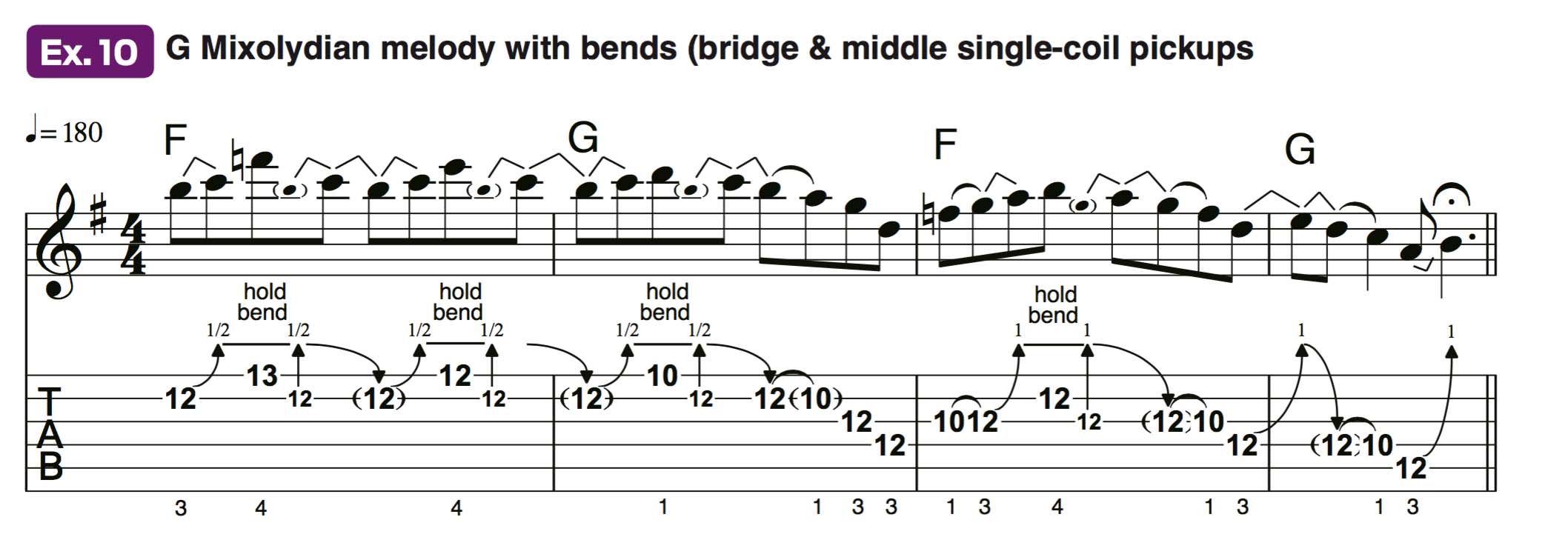

Our next batch of examples exploits the two-finger modal box while also attaching some neighboring scale tones. Ex. 10 is a country-flavored outing derived from the relative G Mixolydian mode (G, A, B, C, D, E, F), which, like D Dorian, is made up of the same seven notes as the parent C major scale.

Bursting at the seams with pedal steel-style bending maneuvers, the passage cascades its way down the magic modal box, inserting only one additional fretted note at the outset, F at the 13th fret on the high-E string. Take great care while performing this example. Be sure to let those sustained bends ring as you pick the fretted notes that are tucked between the bends and pre-bends.

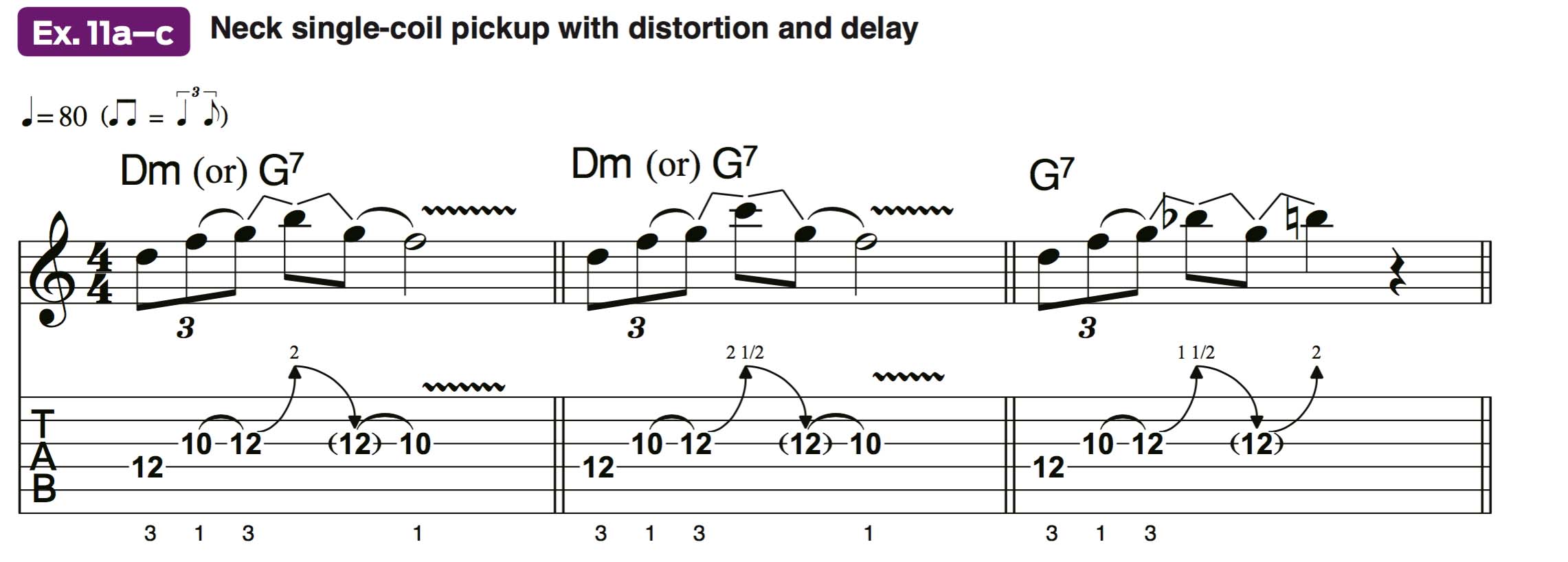

Examples 11a–c all feature overbends. Ex. 11a applies a major-3rd bend (two whole steps) to the 12th fret of the G string (G bent to B) for a lick that could service either a Dm (D, F, A) or G7 (G, B, D, F) chord harmony.

Ex. 11b is essentially the same lick but featuring a whopping perfect-4th bend (two and one half steps) applied to the same fretted note (G bent all the way up to C).

The bluesy lick in Ex. 11c features a multiple, or compound, bend, wherein a fretted note is first bent to one pitch and then to another.

Here, the 12th-fret G note is bent up a minor 3rd interval (one and a half steps) to Bb, released then bent again, this time up a major 3rd, to B. With an interesting set of notes (D, F, G, A, Bb and B), the melody takes on the quality of overlapping G minor pentatonic (G, Bb, C, D, F) and G major pentatonic (G, A, B, D, E) tonalities.

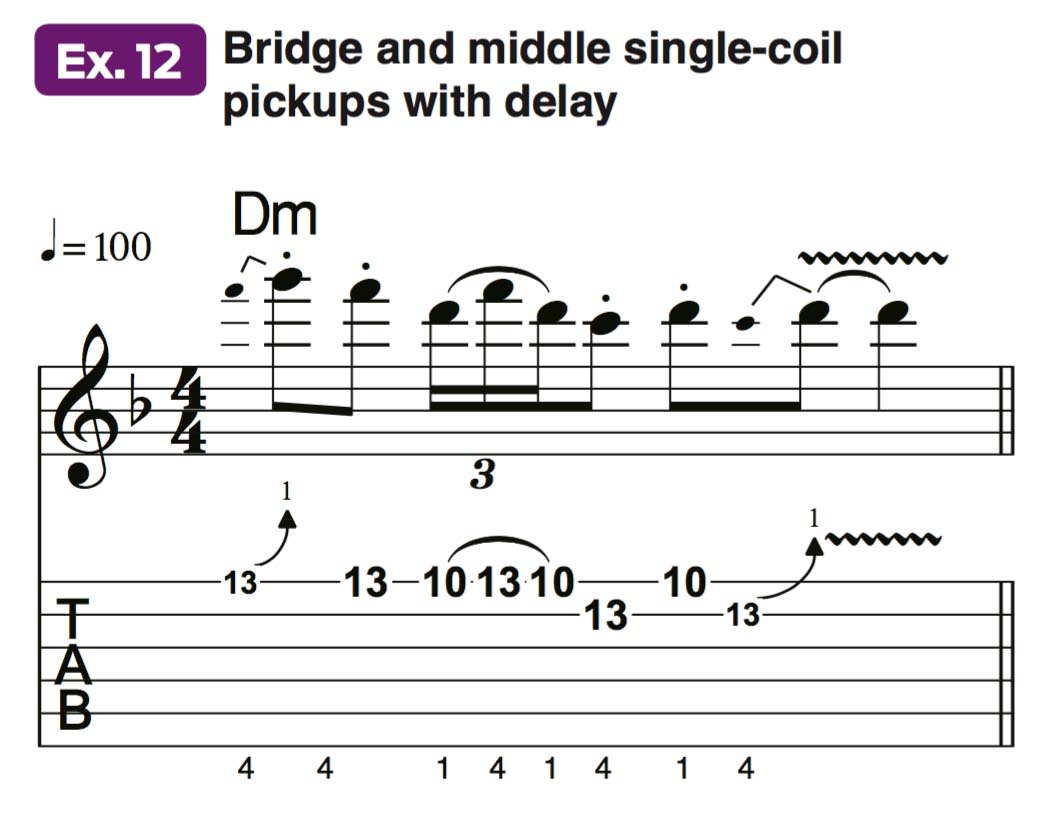

Ex. 12 utilizes the D minor pentatonic (D, F, G, A, C) structure of the D Dorian pattern from Ex.4a for a Clapton-esque lick ending in a bent-note vibrato quaver (see Ex.2b).

The Jimmy Page–inspired passage in Ex. 13 is cast from the same scale mold, but carefully crafted half-step bends imply a D blues (add 3) scale (D, F, F#, G, Ab, A, C) tonality.

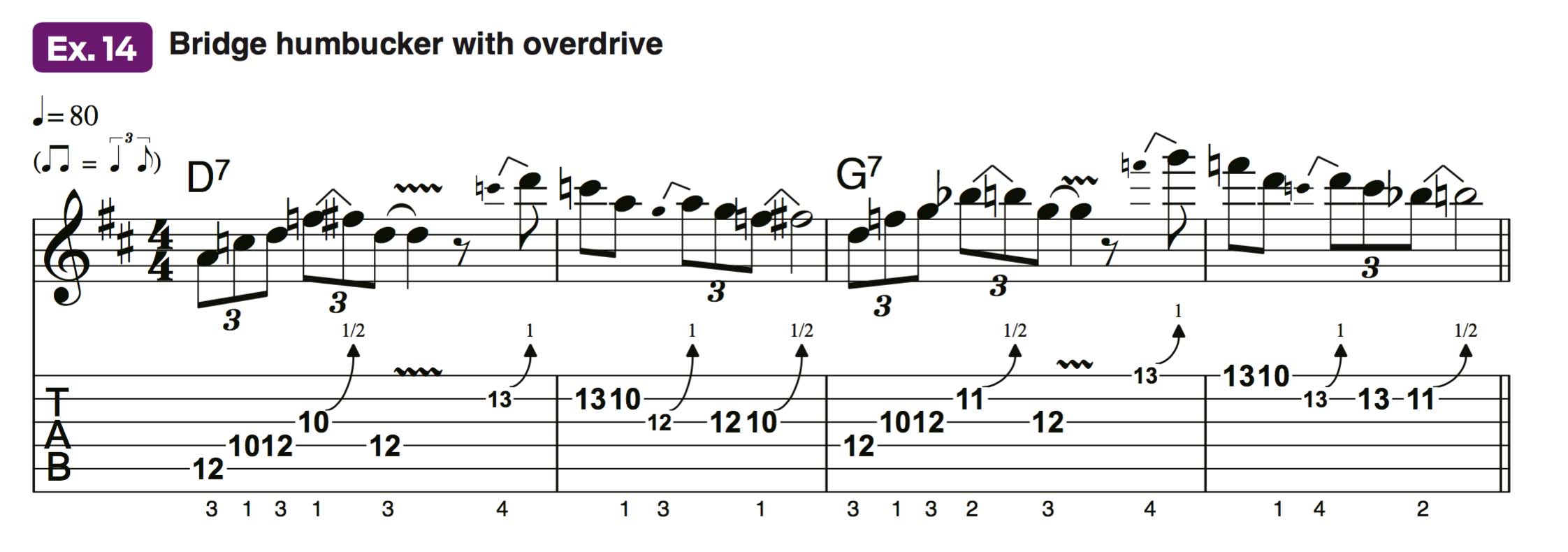

The 10th-position phrasing in Ex. 14 is in the style of master blues guitarists such as Albert King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Joe Bonamassa.

The setting is an isolated section of an 8-bar blues in D, where the I chord (D7) moves to the IV chord (G7). Bars 1 and 2 stay put in the D minor pentatonic box, but a half-step bend at the G string’s 10th fret creates a bluesy minor/major interplay over the D7 chord harmony (D, F#, A, C).

Bars 3 and 4 stay in 10th position while segueing to a G minor pentatonic (G, Bb, C, D, F) box, again spiced with a minor/major (Bb to B) bendy rub over the G7 chord (G, B, D, F).

Chord-Tone Bending

We’ve seen how bending techniques can be used to spice up scale-oriented licks and phrases. Now let’s check out various ways in which they can be used to add pizzazz to basic chord shapes.

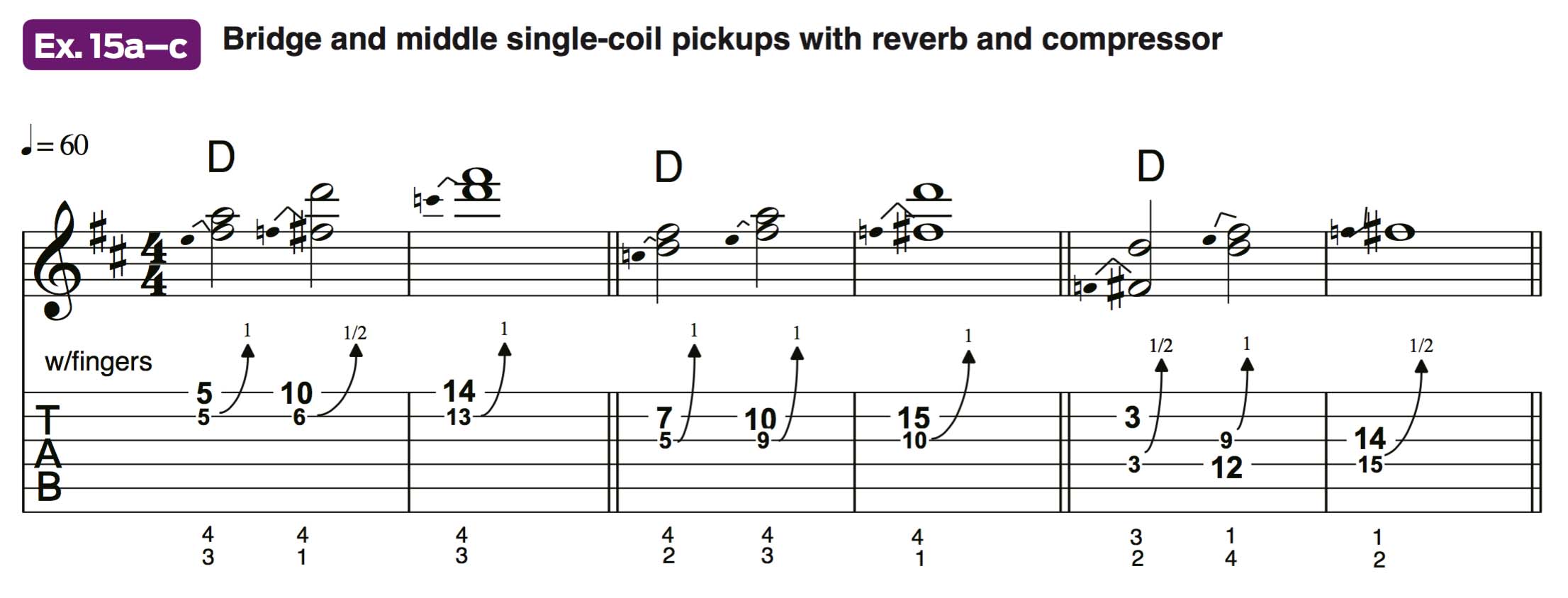

Examples 15a–c illustrate a pedal steel-style approach to major triad inversions using a variety of oblique-bend tactics. (For the sake of continuity and comparison, all three phrases are in the key of D, but feel free to transpose them to other keys.)

Ex. 15a shows three different dyad shapes on the B and high E strings. The first one places the 5th of the chord, A, on top, then the D root and finally the major 3rd, F#. In all cases, the high-E string note is the fixed pitch and the B string receives the bend up to one of the other chord tones.

Ex. 15b uses similar tactics but on the G-B string set, which are tuned differently, so the shapes are different. Be careful with the index-finger bends here. You need to develop pure brute strength and control to bend with your index finger alone, as you can’t rely on any help from the other digits.

Ex. 15c perhaps presents the biggest challenge. First, the D string can be somewhat cumbersome to bend, and bending the G string toward the floor on the second dyad can feel a little strange at first. These are traditional moves for country guitarists, but for blues-rockers they can take some getting used to.

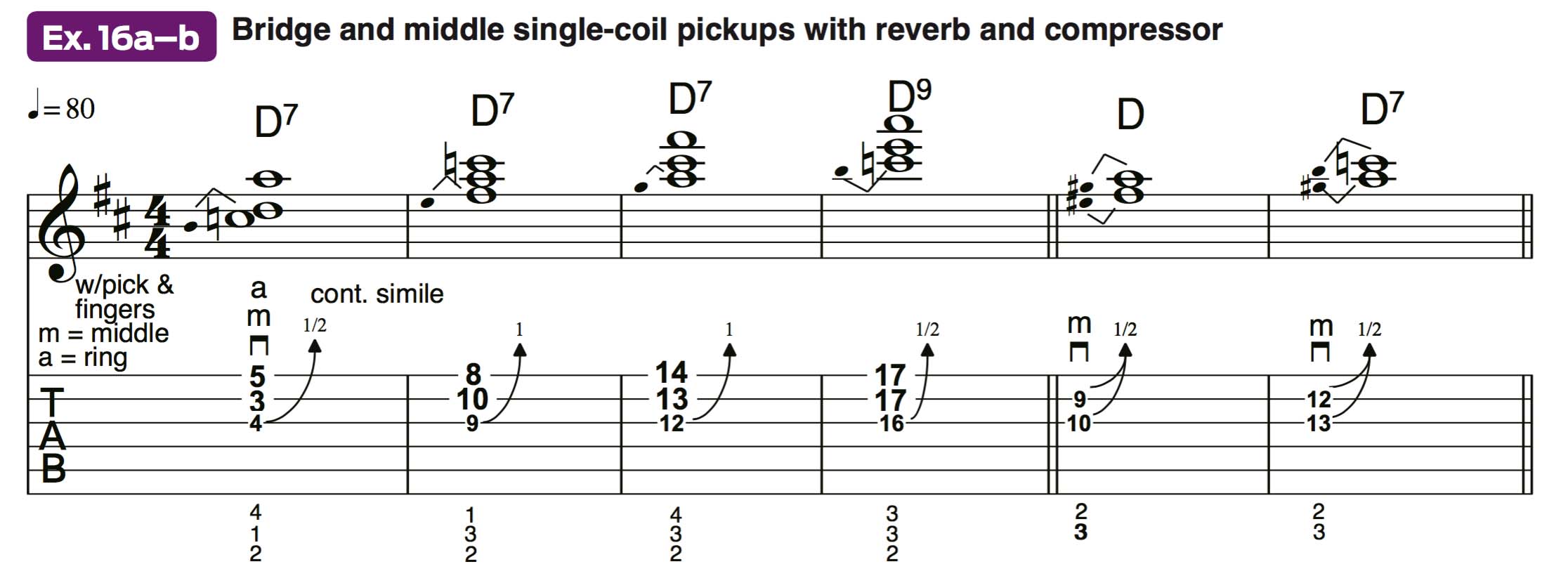

Ex. 16a raises the bar on the previous dyad-based maneuvers with a set of four triple-stop bending ploys.

Each is constructed from a chord-tone dyad voiced on the B and high E strings with the G-string note receiving either a half- or whole-step bend to complete the triad voicing. Ex. 16b features two intriguing dyad bends that, when performed properly, imply the harmony of a D major triad and a partial D7 chord voicing.

These are rather unorthodox moves, but hopefully it will whet your appetite to explore and discover what you can come up with in creating bendy chord shapes. With a little forethought, theory knowledge and ingenuity, the possibilities are, quite literally, endless.

A Bendy Solo

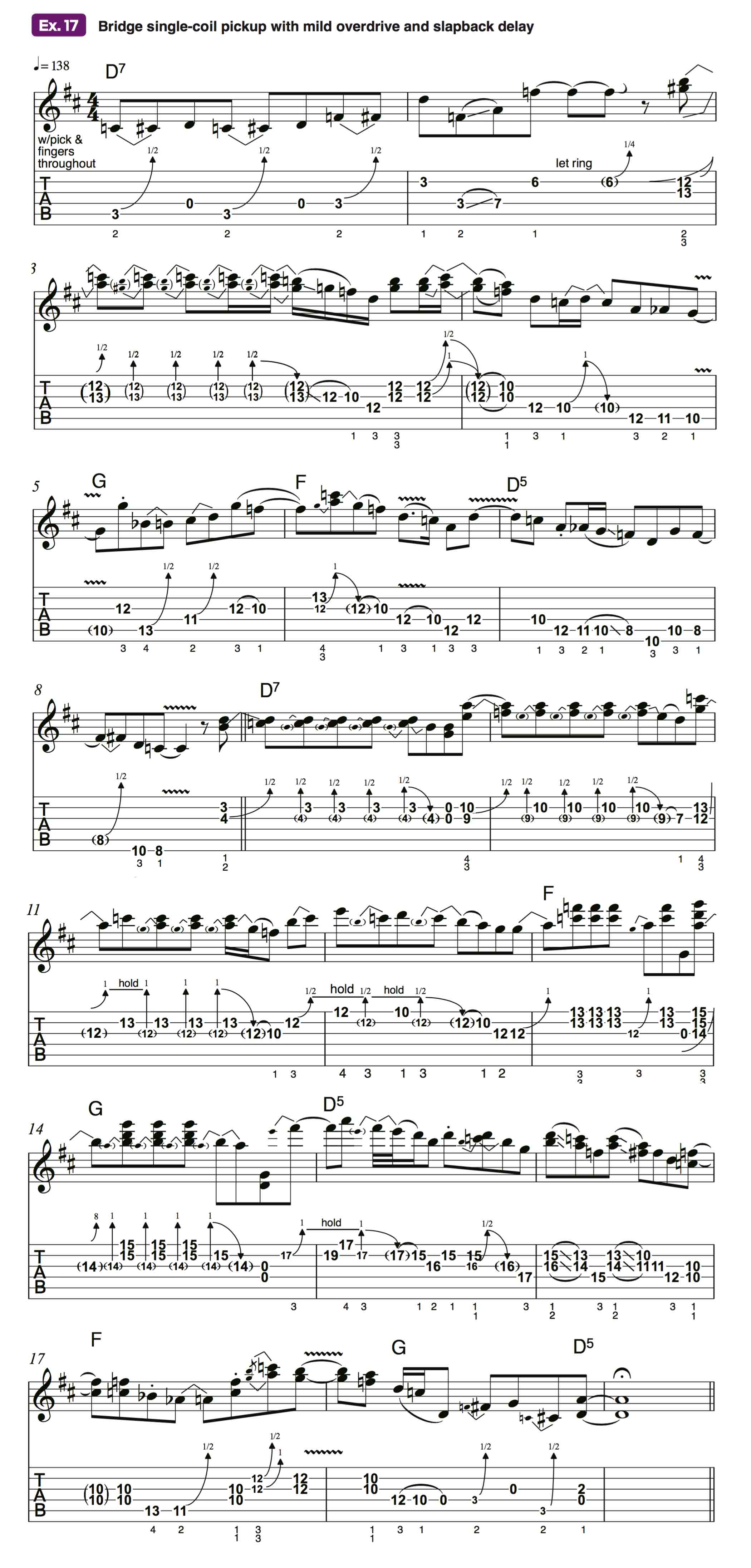

Let’s take some of these bending maneuvers out for a test drive – see Ex. 17. The setting is a straight-ahead, southern-rock flavored groove over a D7 chord with occasional F and G chords thrown in to turn the dominant-7 tonality a bit toward the minor side.

The solo opens with a chromatic line (C, C#, D), courtesy of a half-step bend from the 3rd fret on the A string followed by the open D string. This leads to a D-string bend similar to the first dyad shape in Ex.15c, and a sliding-6th interval culminating in a bluesy quarter-step bend that enters the ambiguous realm between a minor- and major-3rd tonality.

Next up is the double-stop bend figure explained in the second bar of Ex.16b, except this bend is held while striking the same set of strings several times. This leads to bar 4, where we encounter another type of dyad bend. This one was explained in Ex.9. (Remember to keep the strings parallel to one another for both the aforementioned bends.)

Measure 5 hosts a couple of sneaky half-step bends that use lower chromatic neighbor tones to bend to the major 3rd (B) and 5th (D) of the G chord change. A classic oblique-bend figure casts an F major pentatonic (F, G, A, C, D) curtain over the F chord in bar 6, and the first section goes out on a couple of solid D blues-scale (D, F, G, Ab, A, C) phrases.

Beginning in bar 9, section 2 opens with a call-and-response theme based on one of Billy Gibbons’ catchy rhythmic motifs in ZZ Top’s “Sharp Dressed Man.” A stripped-down version of the first triple-stop bending maneuver in Ex. 16a (high-E string is omitted) provides the platform for the “call” phrase.

The “response” in measure 10 employs a half-step version of the classic oblique bend from Ex.2d, creating a minor-3rd rub over the D7 chord. The “concluding” phrase in bars 11 and 12 starts with the full-on oblique bend from Ex.2d, followed by a variation on the pedal-steel phrasing introduced and explained in Ex.10.

What follows is a Stevie Ray Vaughan-style triple-stop version of the classic oblique bend from Ex.2d, creating an F triad tonality (F, A, C) in measure 13, and a G triad (G, B, D) in bar 14. The finale is action-packed, so let’s break it down a bar at a time. Measure 15 is a D Mixolydian (D, E, F#, G, A, B, C) version of the pedal-steel phrasing presented in Ex.10.

But here we’re in a different-shaped box pattern between the 15th and 17th frets. The trickiest thing here is the complex rhythm structure. Work through it slowly at first before you attempt to play it up to tempo.

The trickiest thing here is the complex rhythm structure. Work through it slowly at first before you attempt to play it up to tempo.

Bar 16 is the only measure (besides bar 7) that doesn’t host a bend, but the line is interesting nonetheless: a trio of bookmatched minor-3rd dyad shapes that carve out a D major pentatonic/D minor pentatonic/D major pentatonic pathway as they zip down the fretboard along the G and B strings.

Measure 17 takes up the bending baton again with a crafty half-step bend at the 11th fret on the A string (causing yet another minor 3rd-major 3rd handoff, this time over the F chord), and a restatement of the 12th-fret parallel-string dyad bend from Ex.9.

At measure 18 a double pull-off to the open D string allows just enough time to dive back down to the bottom of the fretboard for the solo-capper – a pair of half-step bends that resolve to their adjacent open-string counterparts, and a final open-position D5 chord.