“I had only one concern: Would Jimi Hendrix like it if he were here?" Carlos Santana on the making of the Supernatural album

On the release of his astonishingly successful 'Supernatural' album, Carlos Santana discussed taking inspiration from Miles Davis, Peter Green's legato lines, and revealed what (and who) finally got him to use a Tube Screamer

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following interview originally appeared in the August 1999 issue of Guitar Player.

“I had only one concern when making my new record,” says Carlos Santana. “Would Jimi Hendrix like it if he were here? Would there be enough guitar? It's important for me to appease Jimi and Wes Montgomery, because I play for them, too.”

We're sitting in Santana's large rehearsal hall in San Rafael, California. Surrounded by bright wall hangings depicting his musical heroes – John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Charlie Parker, and Bob Marley – Santana is describing the genesis of his latest album, Supernatural.

Featuring collaborations with an intriguing assortment of musicians – including Lauryn Hill, Wyclef Jean, Dave Matthews, Everlast, Rob Thomas of Matchbox Twenty, Eagle Eye Cherry, Ozomatli, and the Dust Brothers – this release is Santana's debut on Arista Records.

“We're still finishing some tracks,” Santana explains, as he cues up “Love of My Life,” a song he co-wrote with Dave Matthews. “In fact, right after this interview I'm going into the studio to put some guitar on 'The Calling,' which I wrote with Eric Clapton. It's time to put that one to bed.”

As the punchy intro to “Love of My Life” emerges from the boom box, Santana's head bobs with the music. “You know what? There is enough guitar in there!”

Santana holds passionate views on a variety of subjects, and whether discussing songwriting, tone, and soloing – or such hot-button topics as spirit guides, self-validation, synchronicity, senility, and suicide – he presents his thoughts calmly, without a hint of rock-star posturing. Santana's speech is as distinctive as his playing, and he weaves his colorful tales of music and mysticism with unguarded sincerity.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Even if you don't share all of his beliefs, his ideas will get you thinking about the guitar and its role in our lives. Santana has survived more than three decades in the fickle music business without losing an iota of his enthusiasm for the 6-string and its great players. We can all learn from that.

Your new record is a remarkably collaborative effort. How did this come about?

“Through meditations and dreams, I received these instructions: 'We want you to hook up with people at junior high schools, high schools, and universities. We're going to get you back into radio airplay.' I said, 'okay,' because a lot of young people are not happy unless they are miserable. You can tell by what's happening at the schools. The vibrations of this music and the resonance in the lyrics will present these people with new options.

“I don't want them to feel like me or think like me – we're all individuals, and we're all unique. But with our music, we're presenting a new octave – a new menu. This menu says: 'We are multi-dimensional spirits dwelling in the flesh, solely for the purpose of evolution.'

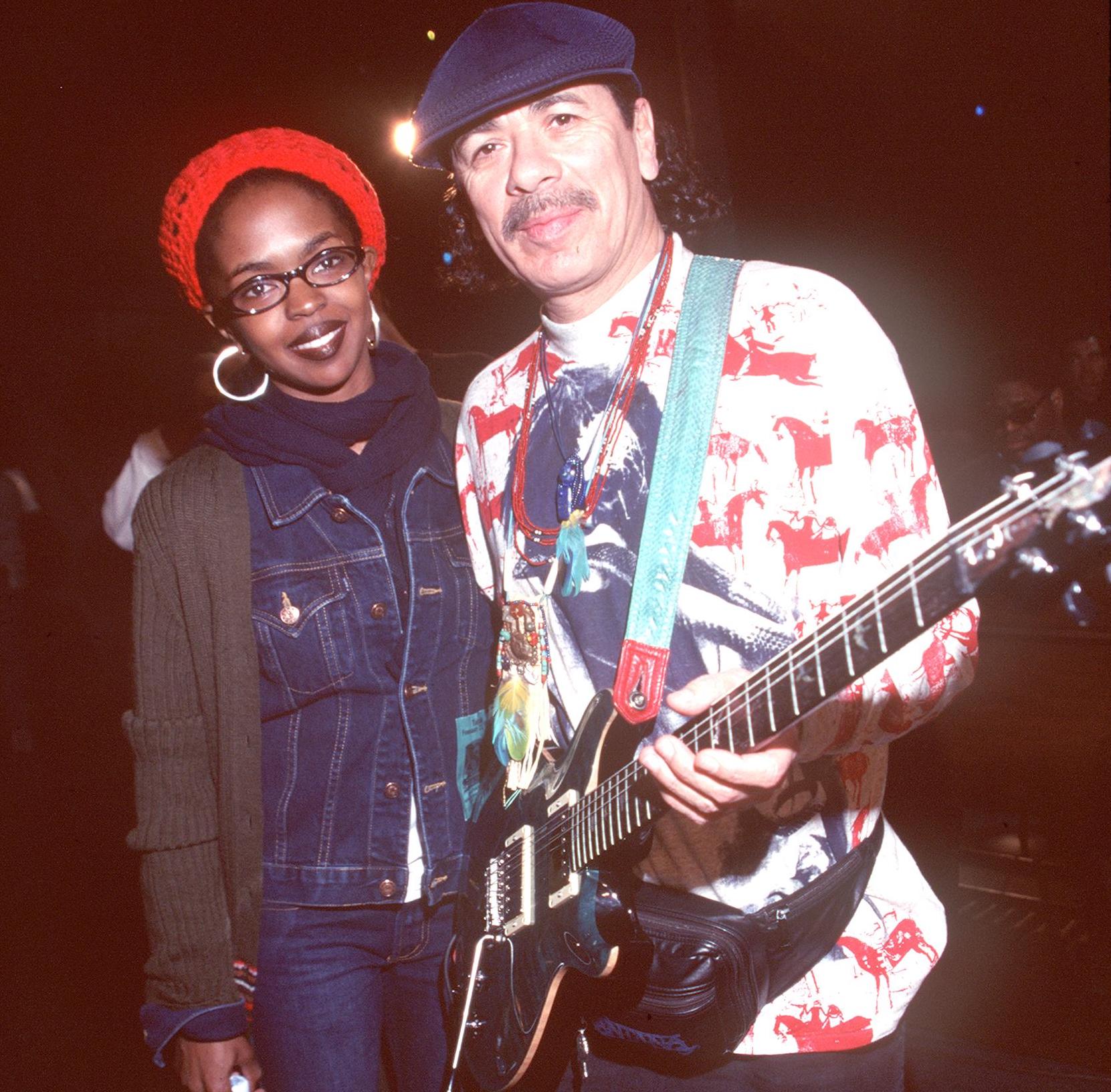

“You see, if you take the time to crystallize your intentions, motives, and purpose, and direct them for the highest good of life and people on the planet – behold, you get synchronicity. I'll give you an example. Working with [Arista label head] Clive Davis, we got hooked up with Lauryn Hill. She said, 'Oh man, I love your music. Since I was a child, I listened to 'Samba Pa Ti' – I even wanted to put lyrics to it.' So, Lauryn invited me to play with her at the Grammy Awards. Playing with her was my first time there.”

And what a night – she won five Grammys.

“Yes, she cleaned up. Eric Clapton was in the audience, and he saw us perform. After the show, he called and said, 'Look man, I heard that people at Arista were trying to contact me to play on your new record. I've been going through some serious changes in my life, and I was at a really critical point, but things are better now. Do you still hear me on your album? Is there room for me?' To hear Eric say that! I grew up listening to him, Peter Green and Michael Bloomfield.”

There are a lot of producers, engineers, and artists involved with this record. They're putting their best foot forward and all being very gracious. I keep pinching myself

Then what happened?

“Well, my spirits are Miles Davis and Bill Graham [the impresario, not the evangelist]. Even though they've left the physical world, they still come in my dreams and give me instructions. So when Eric asked if there was room for him on the record, I could hear Bill saying, 'No, you schmuck, you're too late!' So I'm on the phone having a conversation with Bill and Eric at the same time.

“To Bill, I said, 'Wait. Maybe you can talk to him like that, but I can't.' And to Eric, I said, 'Yeah, but you know what? I wouldn't think of dipping you into something that has already been recorded. Why don't you come over, and we'll write something from scratch?

“And that's how we started. We went through a couple of things and settled on something I had written, but never recorded. It has a Prince bass groove, but it's very swampy – you could hear John Lee Hooker or the Staple Singers playing it.”

So that's synchronicity at work?

“Exactly. Here's another example: Last summer, I asked an artist named Michael Rios to create a poster for us. I marked some passages in a few books and asked him to start with those ideas and then continue with his own vision. Do you know what's really amazing? The images for lyrics that Dave Matthews, Everlast, Wyclef, Lauryn Hill, and Eagle Eye Cherry brought to the album are all in the poster! I didn't tell them to look at it or anything. So, I know there is something happening.

“It was like that from '69 until '73, and then it went somewhere else. Now it's happening again with this music. I'm in total awe of how fast and smooth things have been. Nobody has had a cow, nobody is bugged out – and there are a lot of producers, engineers, and artists involved with this record. They're putting their best foot forward and all being very gracious. I keep pinching myself. I feel very incidental – I just show up, we see each other's eyes, we hear the music, and we start recording.”

How do you describe your music?

“I don't see myself playing black music or white music or gray music. I play rainbow music. It's like diamonds – all the colors are there, but it's still clear.”

What's the process when you co-write a song with, say, Dave Matthews? Do you send tapes back and forth, or do you write in the studio?

“There's a story behind that one. When my father passed away two or three years ago, I didn't listen to music for four days – that's a long time for me. I was picking up my son from school, and I thought, okay, time to listen to some radio. I turned on a classical station, and the first thing I heard was this melody [gently sings a slow, six-note theme]. The melody just stayed with me. They didn't say who the composer was, but I thought it was Strauss.

“I wanted to find out what this was, so I went to the classical music section at Tower Records and said, 'All I have is this melody.' I sang it, and the guy goes, 'Oh yeah. Brahms' Concerto No. 2.' They get me the CD, and that's the song! I said, 'Damn, you guys are good!'

“So, I brought this melody to Dave Matthews in New York. I said, 'I hear this with a 1999 bass.' I also recited these lines:

You're the love of my life/You're the breath of my prayers/Take my hand, lead me there/ With you is where I want to be

“Dave sat down and – bam – wrote the song lyrics right there on the spot, and we recorded it.”

When you listen to vocalists like Aretha Franklin and Dionne Warwick, you learn to phrase differently

Your guitar melody swings a bit more than the Brahms theme.

“If Brahms were alive today, he would swing it, too, because it's what's happening. Listen to Dave's phrasing – he sang it like Billie Holiday or Frank Sinatra – way behind the beat. It's that human thing. Only squares sing in the middle.”

As always, your guitar sound is very vocal.

“When you listen to vocalists like Aretha Franklin and Dionne Warwick, you learn to phrase differently. For a long time, I wouldn't listen to guitar players – Joe Pass, Pat Martino, Jim Hall – because I felt that was another generation's music. I felt my music was blues and rock. But now, I'm discovering all this music by Jim Hall, Kenny Burrell, and Wes Montgomery, and it's like, 'Oh, this guy is burning just as hard, but with a different fire.'

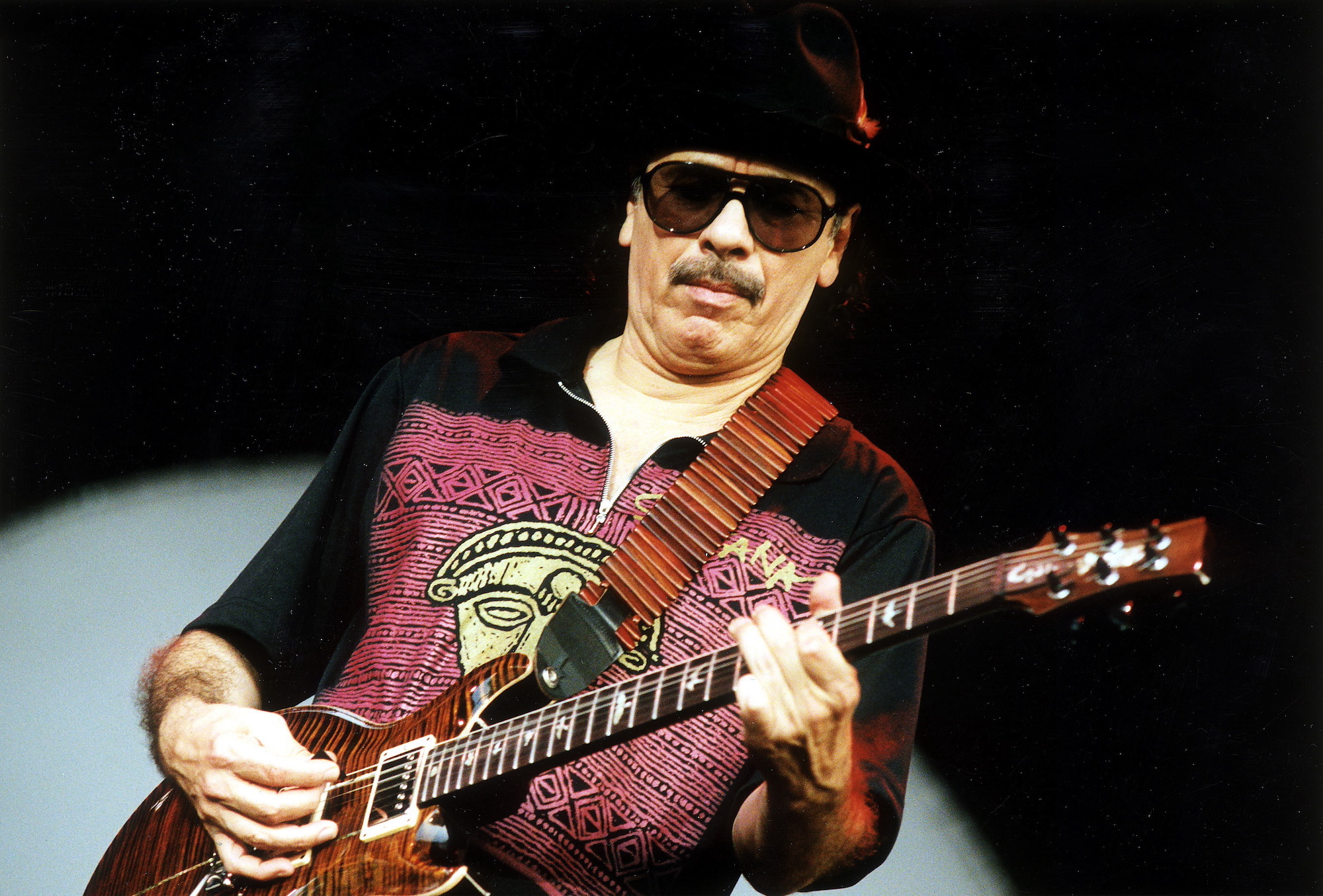

“I'm able to check out all the guitar players, take what I need, and still make those notes like Miles – you know, when you hit that note, you don't want to breathe until you finish with it. You go [exhales].

“Miles, Peter Green – there are very few people who make you hold your breath until that note is ended. You literally feel like you've got a colic in your stomach. You get goose bumps. I love musicians who make you want to cry and laugh at the same time. When they go for it, you go with them, and you don't come back until they come back. [Laughs.] There are not that many players who can consistently do that. Potentially, we all should be doing it.”

Were you listening to any particular musicians while working on this album?

“I was listening to Peter Green, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis.”

What were you listening for?

“Peter Green for his legato tones. I mean, the first four or five years of Peter Green, because lately he plays more like Pat Martino. Staccato notes – [like] John Coltrane. And from Miles, you get the alchemy of making 50,000 notes into five. But with those five, you shake the world.

“That was Miles' supreme gift. He could play two or three notes and, man or woman, you'd just go, 'Oh, my God.' Listen to Sketches of Spain. Play your guitar and try to keep up with the notes, the way he holds them, the breath of it. That's the voice of angels, man.

“You see, great music comes not from thinking, but from pure emotion. As the Grateful Dead people say, 'it's when the music plays you.' You make the best music when you're not conscious of doing it. I've been saying these things since the beginning.

“I remember getting in trouble with Frank Zappa – I'm pretty sure he coined the phrase, 'shut up and play your guitar' for people like me, because we talk a lot! But I am passionate about turning on massive amounts of kids and pulling them out of that miserable state. I want to turn them over.

“You don't have to be Jimi Hendrix or Charlie Parker – you can get it done in your own way. God made the world round so we can all have center stage. Everybody is important, as long as you're doing it from your heart. Frustration and depression lead to homicide and genocide, but inspiration and vision lead to a spiritual orgasm.”

Can you describe this?

“It's where you're constantly happy, and you don't have to feel weird when people say, 'Man, what are you laughing about?' I'm laughing because I know the secret of life. And the secret of life is that I have validated my existence. I know that I am worth more than my house, my bank account, or any physical thing. When I hit that note – if I hit it correctly – I'm just as important as Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, or anybody. Because when I hit that note, I hit the umbilical cord of anybody who is listening.

“When you hit a note like that people say, 'What kind of guitar is that? What kind of speakers are you using? What kind of strings?' No, man. It's not all that – it's the note. Now when you explain this to kids, they say, 'Really? I can do that too?' Sure. We can teach you how to put five things into one note. [To illustrate, Santana holds out the karate edge of his hand, and then rotates it to reveal his palm and five fingers.] These are the ingredients for being a complete communicator: Soul, heart, mind, body, cojones. One note.

“I validated my existence before I got out of high school. People would ask, 'What are you going to do when you leave school?' I'd say, 'I'm going to play with Michael Bloomfield and B.B. King.' They thought I was crazy! I'd say, 'Why are you laughing?' They'd say, 'Man, you're tripping.' 'No, you're tripping because you don't know what you want to do. I know what I want to do, and I know who I'm going to be doing it with. And I'm going to play with those people.

“Once you learn to validate your existence, you have the wind in your sails – where do you want to go? – and you can never commit suicide. I would say that as great as Danny Gatton was, he never took the time to validate his existence. When you feel that the world is not appreciating your genius, you're already setting yourself up to be a victim. There are a lot of musicians like that: 'My manager ripped me off. My record company ripped me off. I'm going to eat beans, but I'm not going to play what they want me to play.'”

Which albums inspire you?

“Tell everybody to hear Spellbinder by Gabor Szabo. That is a must for anybody who plays guitar. He's the person who I credit with pulling me out of B.B. King. B.B. had us in a headlock – Michael Bloomfield, Peter Green – we were all under his spell. Gabor played like a Gypsy, but different from Paco de Lucia. I first heard Gabor with [drummer] Chico Hamilton. The band had no piano player. It was just congas, timbales, and drums with Gabor and [bassist] Ron Carter. It sounded unbelievable.”

So Spellbinder is one of those “Holy Grail” recordings?

“Exactly. Also 'The Supernatural' by Peter Green, Bola Sete's At the Monterey Jazz Festival, and Wes Montgomery's Goin' Out of My Head. Unplug the phone, sit down with these, and you're in for a real surprise.”

If someone was searching for essential Santana, which of your records would you recommend?

“For pure songs, Abraxas. For pure guitar, I would say Caravanserai. Neal Schon and I played really well on that album. At the time, the Allman Brothers had two guitar players. I remember Miles [Davis] was really upset with me because I had another guitarist, but I told him, 'I think Neal is a great guitar player, and that's what I hear right now.' I believe it worked.

The only thing that I have is my tone. That's like my face. Your tone is your fingerprint and your personality. Don't mess with that. Otherwise, you can get anyone from L.A. who just does it with pedals and sounds like a beer commercial

“Later, Neal went to do his thing with Journey, and because I still craved to play with another guitarist, I played with John McLaughlin. Once I got that craving out of the way, I wanted to learn why I was so fascinated with Coltrane and that sky-church music, as Jimi called it. So I got together with [pianist and harpist] Alice Coltrane, and I found out why she writes, and how she writes those celestial strings. It's important for guitarists to listen to her and [tenor saxophonist] Pharoah Sanders.”

How do you write songs? Do you keep a tape recorder running to document your ideas?

“All the time. I play for two or three hours and keep flipping tapes. I mark them and then come in the next day and listen to them. After a half an hour, I might say, 'Ooh – right there. Let me transfer this.' I keep another tape recorder filled with little nuggets of all that rambling. That's what I present to Eric or Dave Matthews.”

So it's a two-stage process – first you capture inspiration, then later you organize those magic moments so you can play them for people.

“Right. That's what I've been doing since I can remember. It works for me. Late at night, if I want to check in with my internal internet, I load the tape recorder, get some nice tones, and play. And sometimes it's okay to watch TV with the sound off. Maybe you're playing music to a car chase, and the next day you go, 'What was I thinking?' Well, you were watching TV and putting music to it.”

I'd be remiss if I didn't ask you about tone and how you got it on this record.

“I'm very honored to be working with René Martinez, who worked with Stevie Ray Vaughan. René can play the hell out of the Segovia guitar. I should be his roadie! He told me everything that Stevie Ray went through to get his tone on tape. Amps all over the place – in the kitchen, bathroom, halls, and everything. Everybody has to find out what works for them.”

What works for you?

“Well, I bring my amps and microphones to every studio, because I found out that when you position certain microphones in a certain way, the room doesn't matter after a while. I have one microphone placed at the amplifier and another one positioned farther back so you can hear [claps] the ghost sound. You can't get that with knobs. They just give you an emulation.”

As you recorded Supernatural in several different studios, was it difficult to get a consistent tone?

“Sometimes I would say, 'Look man, you're giving me a snapshot of me. Imagine I'm a singer – you're only giving me head tones, nose tones, and throat tones. I want the chest tones and belly tones – even toe tones! Give me the whole thing. That's why I've got a Marshall.'

“The technician might say, 'I don't know what you mean.' I'd say, 'You want to know what I mean? Open the damn door.' As soon as he'd open the studio door, I'd say, 'Hear that sound coming in? I want that in the speakers. I don't want to sound compressed and chopped. I don't sound like that.' Sometimes, I'll help place the microphones – and now I even bring my own engineer, Jim Gaines.

“The only thing that I have is my tone. That's like my face. Your tone is your fingerprint and your personality. Don't mess with that. Otherwise, you can get anyone from L.A. who just does it with pedals and sounds like a beer commercial. That's okay for them, but I learned by listening to T-Bone Walker and Peter Green, so I have a tone.”

You mentioned Marshalls. What amps did you use for this record?

“I used Marshalls, Boogies, and Twins. I went through my six Marshalls and got rid of the ones that weren't consistent. Some you plug in and it's glorious. Some you have to baby-sit and change diapers and change tubes. I found the ones that are happening in the studio or a coliseum or anywhere, and I kept those. We mark them – these speakers go with this head. That way, you're not shooting in the dark. You know exactly what you're going for when you're recording.”

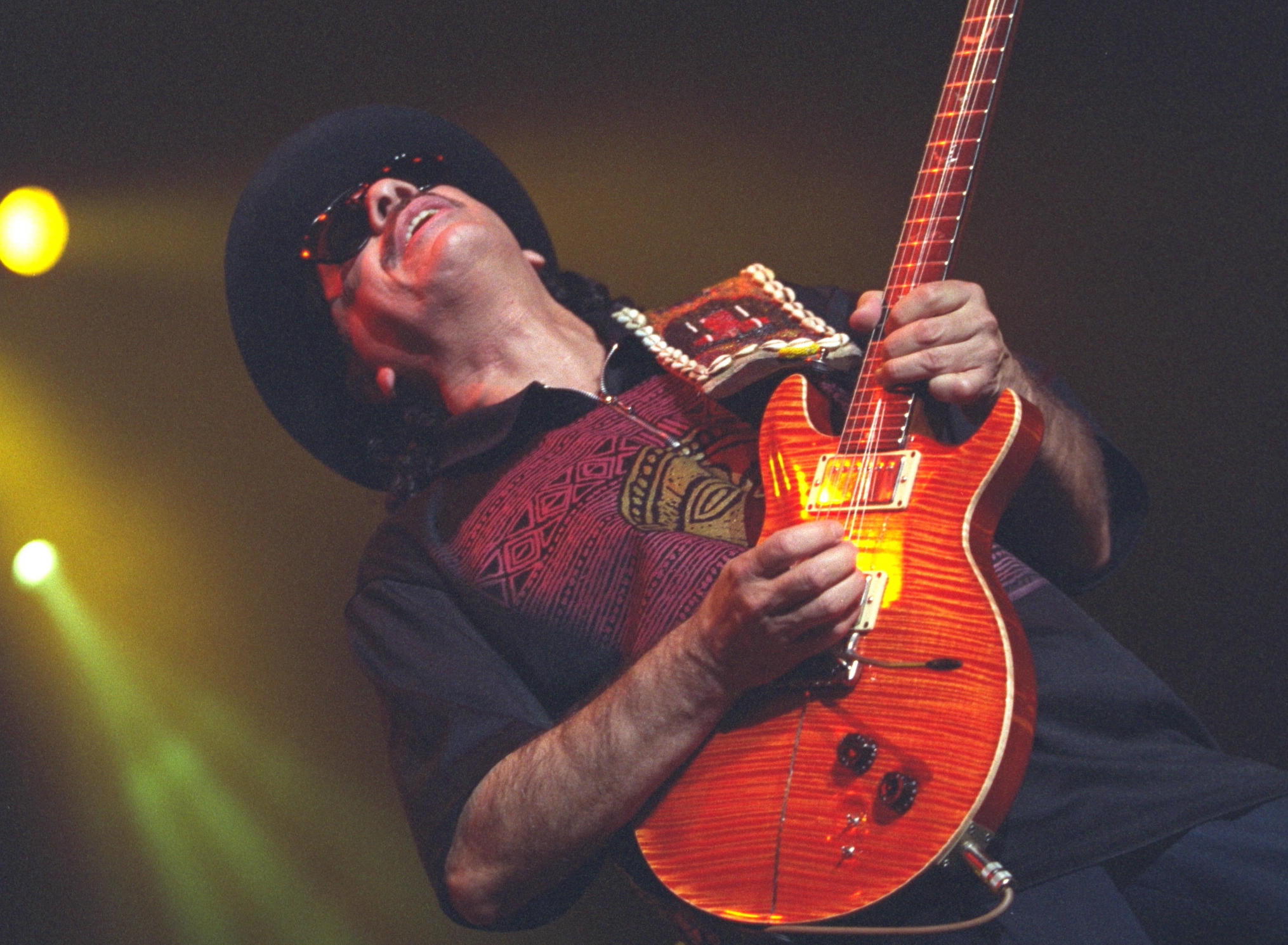

Are you still playing your signature PRS?

“Still the PRS, although with Eric, we both played Strats because I wanted to keep it even. It's such a pretty tone. Because of René, I finally played through a Tube Screamer. In the past I always said, 'I'll never use those things because I want to sound like me.' I would just mark the floor in the places where my guitar sustains. When I'm onstage, there are marks for this song, marks for that song....”

Do you mark the studio floor, too?

“Oh yes. At first I told René that I didn't want to play a Strat, because to make it sustain, I'd have to play so loud that I didn't know if I could have babies! So he goes, 'You don't have to play that loud. Try this Tube Screamer.' So we plug it in and – bam – it sustains right through a Twin or a Marshall.

“You can still talk, but you're sustaining furiously. I said, 'Oh, I shouldn't have been so bullheaded. I'm so stubborn.' And he says, 'You didn't know. Stevie used pedals to sustain.' I went, 'No kidding? I thought he was just loud.'

“It has been a real education working with René. In fact, the entire process of making this album is new to me. Even though I've been recording since '67, all of a sudden I'm thrown into a whole new way of doing things. I really like it – it's fresh and very challenging.”

Any advice for fellow guitarists?

“The last thing I want to say is that whether you play blues, bluegrass, or jazz – whatever – realize that when you get older, you either get senile or become gracious. There's no in-between.

“You become senile when you think the world short-changed you, or everybody wakes up to screw you. You become gracious when you realize that you have something the world needs, and people are happy to see you when you come into the room. Your wrinkles either show that you're nasty, cranky, and senile, or that you're always smiling.

“That's why I hang around with Wayne Shorter, John Lee Hooker, Herbie Hancock – people who have passion. I've never seen them bored. I'm like a kid – I'm 51 years old, but I still feel like 17. I got the recent Guitar Player at my house yesterday, and I sat down and read it. It's the only magazine I read from beginning to end, nonstop.

“Most magazines are very biased into one octave. Your magazine covers women and men, the gifted and the beginners, brilliant and crazy garage bands – all of it – and I relate to that. Whether you've got a green mohawk or a suit and a tie, it's still the same: Are you saying something valid? Are you contributing, bringing new flowers that we haven't seen in the garden?

“I'm looking at the new guitars and new amplifiers like a painter discovering new brushes or mediums. That fascination with instruments and sound and texture hasn't gone yet. It's really fun.”