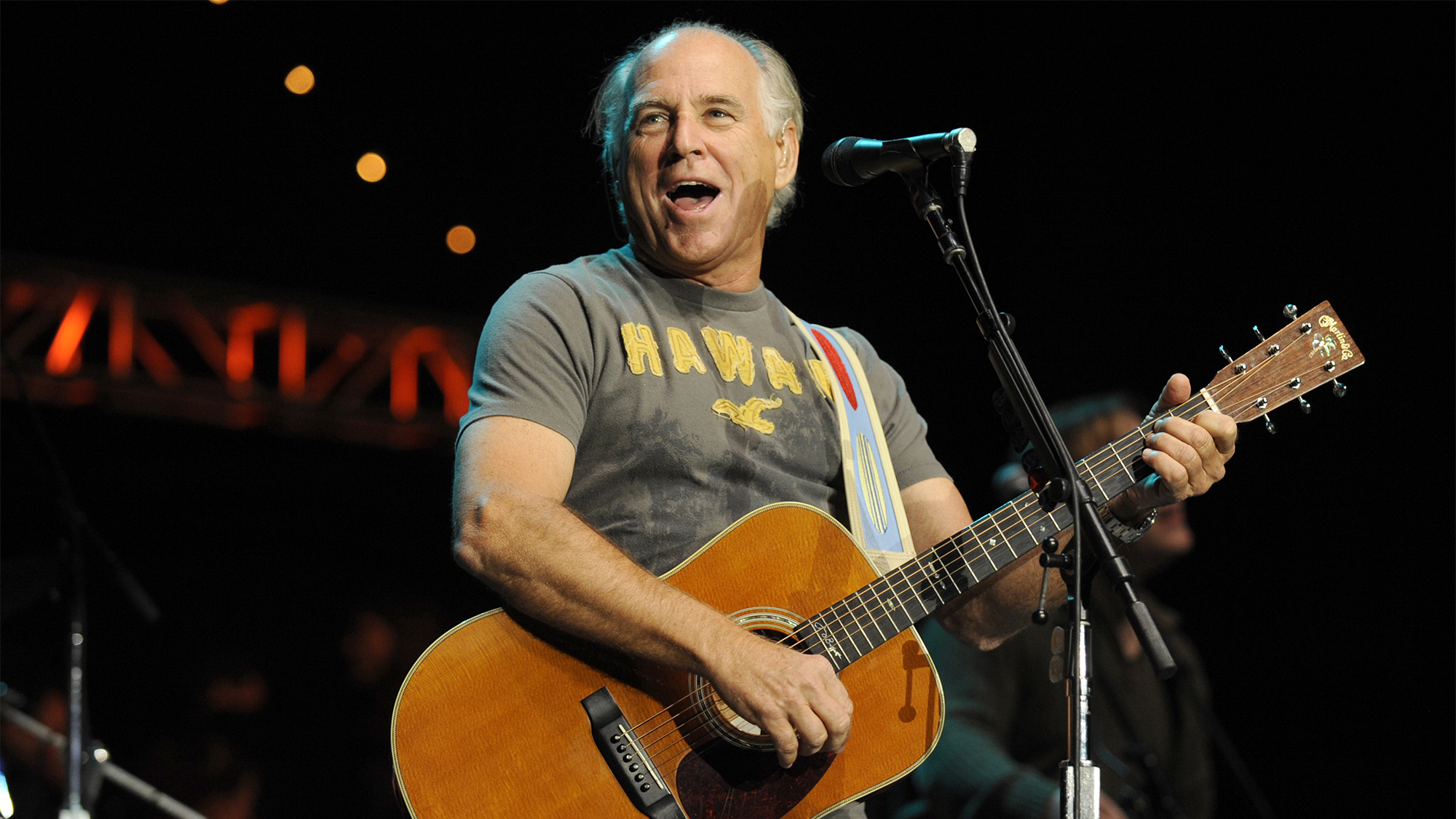

“That’s a terrible idea for a song!” “Margaritaville” writer Jimmy Buffett didn’t listen to his critics. Here’s how a bad day, a traffic jam and a rejection from Elvis Presley turned out just fine for him

After years of struggling in Nashville, Buffett turned his musical ambitions south, to the Gulf Coast, and created a generation all his own

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ever feel like everything was working against you? Jimmy Buffett knew the feeling well. Several albums into his career, he was still fighting headwinds. He’d been unhappy with his old producer and felt stuck recording in Nashville. To make matters worse, his new producer wasn’t keen on a song he’d just written that had been inspired by a perfectly awful day he’d had at the beach.

Remarkably, the tide was about to turn in his favor with his aptly titled new album, 1977’s Changes in Latitiudes, Changes in Attitudes. And it was all thanks to that bad day on the beach.

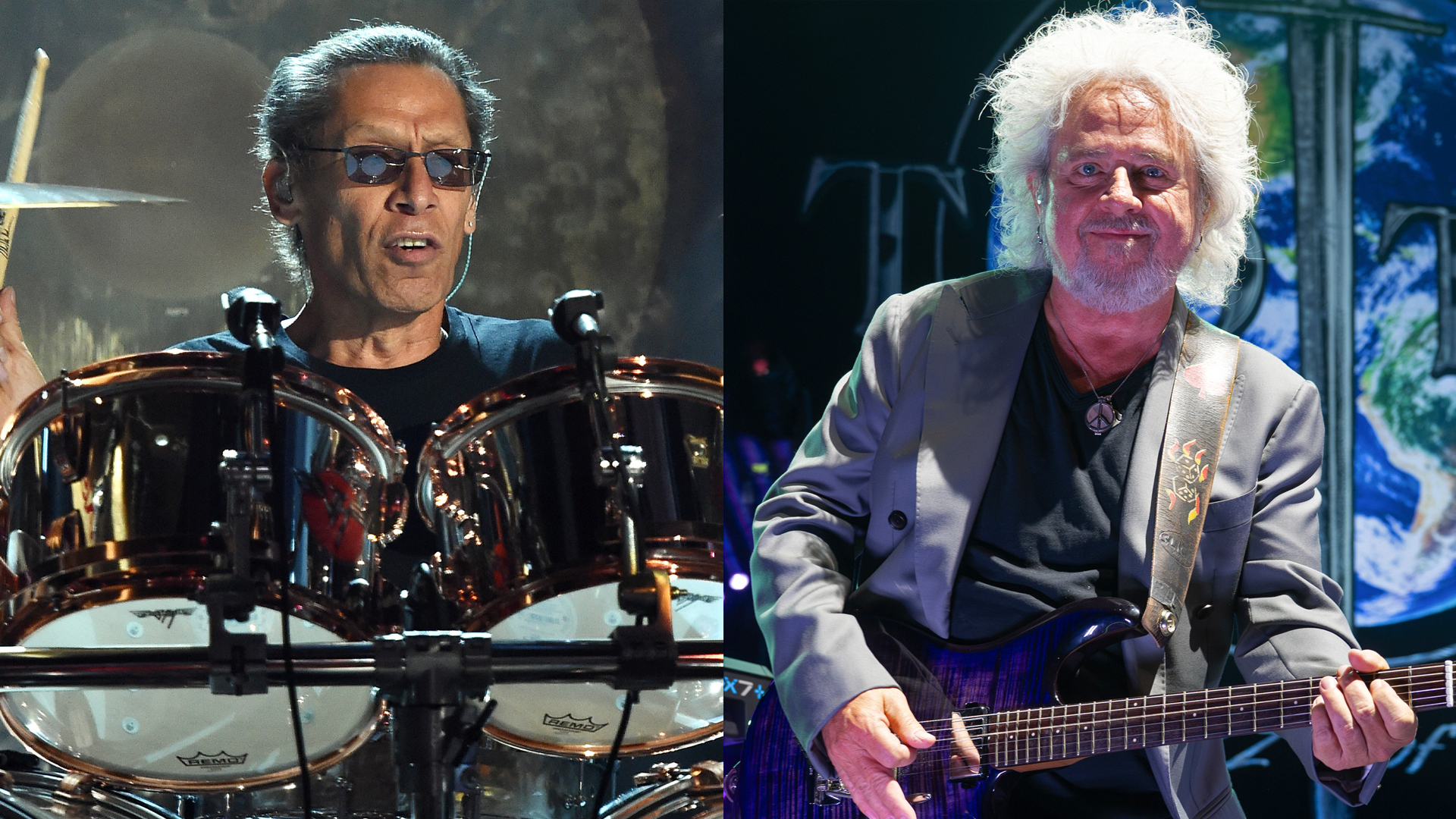

Norbert Putnam, producer for, and co-founder of, Quadrafonic Studios in Nashville, was in charge of the album’s sessions. Although it was his first record with Buffett, they weren’t strangers. They’d had known each other since at least 1971, when Quadrafonic was launched.

“I had known Jimmy Buffett for a few years when he was in Nashville," Putnam told Sound on Sound. “He used to hang around Quad a lot.”

Buffett liked to drink, and fortunately for him, the Quad had a lounge with an open-bar policy. “Anyone could come into the studio and drink for free as long as they didn't bother the clients,” Putnam explained. Buffett was among the crowd, which included artists like Guy Clark, Mickey Newbury and Jerry Jeff Walker. The two men got to know each other well.

But Buffett was unhappy in Nashville and, in particular, his lack of success. His first album, 1970’s Down to Earth, “didn’t do shit,” as he colorfully put it, and his second, 1971’s High Cumberland Jubilee, didn’t getting released after the label — perhaps worried about poor sales — claimed it lost the master tapes. (They were found in 1976.)

Worst of all for Buffet, he had recently lost his beloved grandfather James Delaney Buffett, a sailor from Newfoundland who had profoundly influenced him and been featured in several of his songs.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

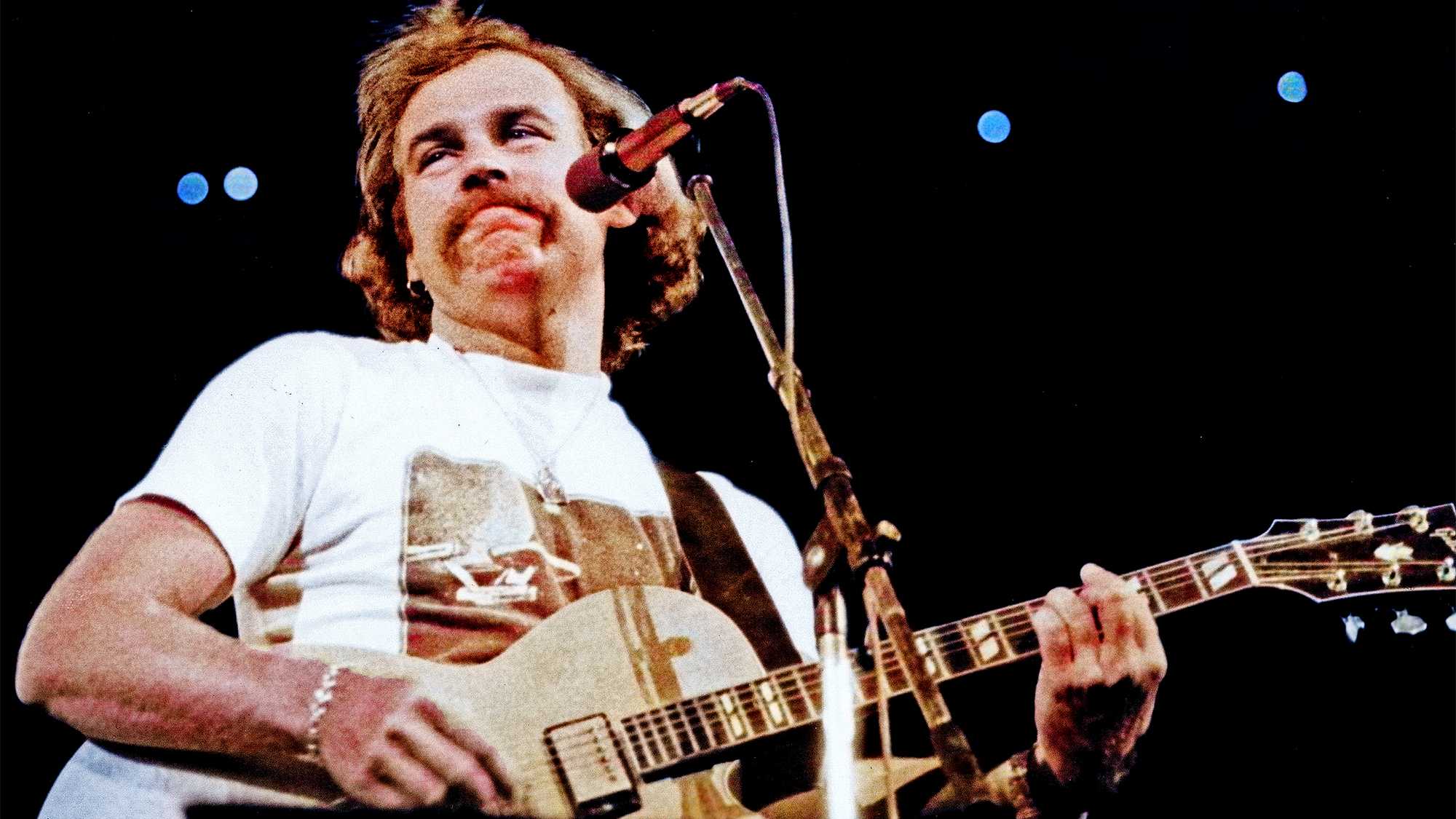

In 1972, Buffett had enough. He relocated to Key West, where the laidback vibe and ocean suited him. He formed his backup group, the Coral Reefer Band, in 1975.

But in the meantime, his albums were still recorded in Nashville. Which is where he pitched a new idea to Putnam. His previous albums had been produced by Don Gant. All of them had been, essentially, country records, and each one had stiffed. He wanted a change of sound, something more pop and yet redolent of life along the Gulf Coast. He also wanted to work with his group, the Coral Reefer Band, instead of Nashville studio hired guns. And he wanted Putnam to do the honors of producing it.

Putnam had his doubts. “A bunch of coked-out musicians behind Jimmy singing songs about his grandfather and the ocean,” is how he imagined the album.

“But after a few more drinks, the idea didn't sound so bad any more,” he admitted.

After going to see the group perform, Putnam told him straight: “’Look, if you want to make records about the ocean, you have to get next to the ocean.’” It was the same approach he’d take with singer-songwriter Dan Fogelberg. “He wrote about the mountains, so I recorded him in the mountains,” at Caribou Ranch Studios, where the Fogelberg’s Nether Lands and Phoenix albums were cut in the late 1970s.

Buffett agreed. Putnam’s studio of choice was Miami’s Criteria, famed for game-changing albums like Derek and the Dominos’ Layla, and parts of the Eagles’ One of These Nights, including its disco-tinged title track.

One day, Buffett came into Criteria complaining about the bad day he’d had. After losing a flip-flop on the beach, he cut his foot on the pull tab from a soda can, then went home to make a margarita, only to misplace his salt shaker.

To Putnam’s dismay, Buffett told him he was drafting his misfortunes into a tune.

"That's a terrible idea for a song,” the producer told him.

Buffett disagreed. He’d been working out the tune on his legendary Painted Lady, a 1969 Martin D-28 acoustic that he bought at George Gruhn’s original GTR shop in downtown Nashville in the 1970s. Gruhn and his repair technician Randy Wood did additional inlay work that recalled that of a D-45.

“That was my ‘A’ guitar,” Buffett said about the D-28 to Acoustic Guitar. “Heck, I only had two guitars at the time — my D-18 12-string and my new D-28.” The “painted lady” was in reference to a mermaid illustration that landscape painter Russell Chatham had applied to the guitar at Buffett’s request.

“We were kind of running around in the mountains in those days doing some psychedelics,” Buffett explained. “Well, we were hanging around the lake with these girls who kinda looked like mermaids, and I said, ‘Russell, why don’t you paint a mermaid on my guitar?’

“When I moved down to Key West full-time, that’s the very guitar I wrote ‘Margaritaville’ on.”

He continued working on the song while he went busking around southern Florida with his D-28. One day, on his way back to Key West, he got stuck in traffic on Seven Mile Bridge. It was the perfect predicament for a songwriter working on a tune about going nowhere. With nothing else to do, he got to work finishing up the final verse to the song.

“Somebody had broken down on the Seven-Mile Bridge,” Buffett recalled years later. “And we were stuck there for an hour. And I just sat out there on the Seven Mile Bridge, just looking out, and I finished the song there.”

Once traffic got moving, he hightailed it to his evening gig at Crazy Ophelia’s in Key West and gave the tune its debut.

“People liked it,” he said. “I went, ‘Wow, this is pretty good.’ And, you know, it was, it was fresh. It was probably six hours old.”

Soon afterward, back at Criteria, he auditioned the song, then titled “Wasted Away Again in Margaritaville," for Putnam and a few others at Criteria. Despite his initial objections, he realized Buffett knew what he was doing.

“He comes back in a few days later with 'Wasted Away Again in Margaritaville' and plays it and right then everyone knows it's a hit song,” the producer told Sound on Sound. “Hell, it wasn't a song — it was a movie."

A movie, perhaps, but reportedly Buffett didn’t intend to record the song himself. The story goes that he offered it to Elvis Presley, who declined the offer. Given that he died soon afterward, it’s unlikely that he would have been able to record it anyway.

Why would Buffett want to give away the best song he'd written? Buffett was an Elvis fan after all. He called out the King of Rock and Roll in 1974’s “Life Is Just a Tire Swing,” and went on to mention him in later tunes, including “Elvis Presley Blues.” He even cut the Steve Goodman tune "Elvis Imitators" under the alter-ego Freddie and the Fishsticks in 1981, with Presley’s backup singers, the Jordanaires, behind him. And like Elvis he was born in Mississippi and played music that defied category.

But he was also, like Presley, a practical joker. Apparently the Elvis and “Margaritaville” connection was a red herring. Buffett would come to regret his jest after his fans became obsessed it.

“On some days, I want to go to them and, ‘Get a life,’ you know?” Buffett said in a 1997 60 Minutes interview. “It’s just made up, you know?”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.